Agustina Vergara CidIn early January, Rahaf Mohammed made headlines around the world. She is the Saudi teenager who fled her home country to escape family abuse and the state-endorsed mistreatment of women in Saudi Arabia.

During a family vacation in Kuwait, Rahaf boarded a flight to Bangkok, where she barricaded herself in a hotel room to resist deportation. Hoping to be granted asylum somewhere, she live-tweeted the ordeal, publicizing her plight. She was in a terrible position — her passport had been confiscated by a Saudi diplomat and her abusive father and brother had come to take her back.

Her family abused her repeatedly. In an interview with the Canadian network CBC, she said: “I was exposed to physical violence, persecution, oppression, threats to be killed.” But it wasn’t just her family she sought to escape — she wanted to flee the country. “Women are treated like slaves in Saudi Arabia,” she explained. “I felt I couldn’t achieve my dreams as long as I was still living there.” To make matters worse, Rahaf had decided to renounce Islam — an offense punishable by death under Saudi law.

Rahaf’s story puts a spotlight on Saudi Arabia’s treatment of women, but this regime is hardly the only villain in the story. There is another: The United Nations.

Fortunately, she escaped the fate of being publicly beheaded: she was granted asylum in Canada.

Rahaf’s story puts a spotlight on Saudi Arabia’s treatment of women, but this regime is hardly the only villain in the story. There is another: The United Nations. The UN had a role in facilitating Rahaf’s request for asylum, but what didn’t make the headlines is the UN’s ongoing complicity in Saudi Arabia’s contempt for the rights of the individual.

This may come as a shock, because it goes against what most of us have been taught about the UN. The UN is commonly portrayed as an agent for good, with a mission to preserve peace and uphold human rights around the world. But the fact is that the UN enables Saudi Arabia’s oppression of women.

Saudi Arabia, a UN member in good standing

Let’s take a closer look at what Rahaf escaped.

There is no rule of law in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia’s justice system is based in Sharia law and lacks a penal code, which leaves the definition of crimes and punishments open to the full discretion of judges. There is no due process and trials are arbitrary. Confessions are often obtained by torture, and for many crimes (such as renouncing Islam) the penalty is public decapitation using a sword.

Zooming in to the treatment of women, it is the norm to force them to marry against their will and for family members to subject them to physical and psychological abuse. Rahaf mentions one instance of such violence: “they locked me up for six months after I cut my hair . . . because it is forbidden in Islam for a woman to look like a man.”

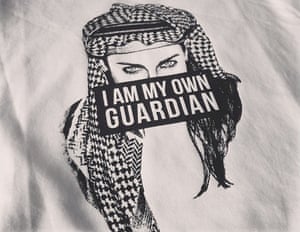

There is a “guardianship” system: male relatives exert total control over women’s lives. In Rahaf’s words: “guardianship rules apply to women for all their lives, until they die . . . the guardian is who makes the woman’s decisions, about her marriage, work, and what she can study.”

Women need permission to do anything of significance — and even relatively insignificant things as well. For example, most public spaces have a separate entrance for men and women and are heavily segregated. Women can’t even try clothes on while shopping. Apparently, women disrobing in “public,” behind closed doors, is blasphemous.

Rahaf was subjected to all of this. “My brother had control over my day-to-day life — what I should wear, what I should eat, where I go, who I can see and go out with.” Essentially, women in Saudi Arabia are treated not as sovereign individuals but as the property of their families.

This is the maltreatment that Rahaf had to endure while living in Saudi Arabia — and, had she not fled, she likely would have been killed.

How has the UN dealt with Saudi Arabia? It is a member of the UN in good standing, with an almost pristine record within the organization.

Saudi Arabia is the regime from which Rahaf fled precisely because of its barbaric treatment of women. By elevating it to a role where it supposedly is concerned with the proper treatment of women, the UN provides moral cover for Saudi Arabia’s crimes.

This means the UN turns a blind eye to Saudi Arabia’s crimes. Take the behavior of the UN’s General Assembly, its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. One of its functions is to issue resolutions condemning member-states (and other international actors) that are in violation of the UN Charter. In 2018, it issued 27 condemnations. None of them were against Saudi Arabia — while Israel, the freest country in the Middle East, received 21 of the 27 condemnations. Saudi Arabia didn’t get a single condemnation despite the fact that in the first quarter of 2018 alone, there were at least 48 decapitationsin the country, most of them for non-violent crimes and carried out without prior due process.

But not only does the UN avoid condemning Saudi Arabia — it also appoints the regime to human rights bodies, including, even more absurd, bodies which allegedly advocate the rights of women. Saudi Arabia was elected to the UN Commission on the Status of Women, to the UN Entity for Gender Equality & Empowerment of Women, and to the UN Committee on Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. What this means is that Saudi Arabia is responsible for monitoring that the rights which it denies are enforced around the world.

Saudi Arabia is the regime from which Rahaf fled precisely because of its barbaric treatment of women. By elevating it to a role where it supposedly is concerned with the proper treatment of women, the UN provides moral cover for Saudi Arabia’s crimes.

A wider pattern

The UN’s enabling of Saudi Arabia goes back years. Well before Saudi Arabia was elected to safeguard the rights of women, it was already a member of the UN’s global watchdog of rights, the Human Rights Council.

Saudi Arabia had never been called out at the Human Rights Council by other member-states — until recently. In a very rare rebuke, a few countries expressed lukewarm condemnation of the regime’s violations of the freedom of the press and of its abusive national security provisions, focusing particularly on the imprisonment of women activists. According to the New York Times, “the statement drew applause from human rights groups, which said it broke Saudi Arabia’s apparent impunity from condemnation in the council.” Let’s be clear: the Human Rights Council didn’t officially condemn Saudi Arabia, only a handful of states did.

The fact that even this is a rare and unprecedented rebuke is telling of the free pass that Saudi Arabia enjoys. The rebuke looks more like a reaction to the international outcry against Saudi Arabia’s recent highly publicized crimes (such as the grisly murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and the crackdown on activists), rather than a serious reckoning over Saudi Arabia’s character and the UN’s whitewashing of it.

The root of the problem

What explains the UN’s ongoing treatment of Saudi Arabia? Does the UN look the other way at the country’s evils because, with the state’s plentiful oil money, it is a major funder of the UN? No, Saudi Arabia in 2019 contributed less than did Spain, the Netherlands or Mexico. The answer lies elsewhere, in the fact that the UN puts all countries on equal footing and grants them power and opportunities, regardless of their moral status.

The UN puts good and bad regimes on par, as if they were morally equal. Ayn Rand likened the UN to a “crime-fighting committee whose board of directors included the leading gangsters of the community.”

This idea was central to the UN when it came into being upon ratification of its charter by the five members of the Security Council. Who were the founding members? Notably, they included the United States, the freest country in the world — but also the Soviet Union, a brutal dictatorship. The permanent members of the Security Council are the US, France, and the UK — along with Russia and China, two countries that repudiate the principle of individual rights.

The UN puts good and bad regimes on par, as if they were morally equal. Ayn Rand likened the UN to a “crime-fighting committee whose board of directors included the leading gangsters of the community.”

The inclusion of Saudi Arabia on the Human Rights Council, for example, is far from an exception. The Council also includes states such as Venezuela, whose government is starving its citizens to death, and Eritrea, a one-man dictatorship where forced labor is rampant and freedom of expression is nonexistent.

Because of the UN’s principle of amoral neutrality, it must give prestige and power to criminal regimes. If the millions of people killed by the Russian and Chinese states does not prevent these nations from being permanent members of the UN’s Security Council, why should Saudi Arabia’s treatment of women prevent it from serving on the UN Committee on Elimination of Discrimination Against Women?

Rahaf Mohammed risked her life to flee the torment of living in Saudi Arabia. Barricaded in a hotel room, she was in danger of being taken by the Saudis. About this, she said: “I was prepared to end my own life before they kidnapped me.”

The fate that Rahaf managed to escape is the hell that millions of Saudi women remain subjected to. Isn’t it well past time to question the legitimacy of an organization that is a willing accomplice to their oppression?

No comments:

Post a Comment