M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Hot photoshoot: Veena Malik shows off her legs and cleavage again

It's been quite a while since we heard of Veena Malik. Her film - the South version of The Dirty Picture made headlines a couple of months ago, but post that, there's been a lull in her fame factor. So, now, she's back with a bang. Recently, she slipped in a pair of hot pants, a tube top and flirted with the camera for a hto photoshoot.

She posed with the hat, played with her hair, bent down a bit (to show you know what) -- basically did all that she could to make it to the newsrooms, headlines, social networking websites all over again.

Is this hot and sensuous or not even close to being tagged as steamy?

It's been quite a while since we heard of Veena Malik. Her film - the South version of The Dirty Picture made headlines a couple of months ago, but post that, there's been a lull in her fame factor. So, now, she's back with a bang. Recently, she slipped in a pair of hot pants, a tube top and flirted with the camera for a hto photoshoot.

She posed with the hat, played with her hair, bent down a bit (to show you know what) -- basically did all that she could to make it to the newsrooms, headlines, social networking websites all over again.

Is this hot and sensuous or not even close to being tagged as steamy?

http://daily.bhaskar.com/article/ENT-hot-photoshoot-veena-malik-shows-off-her-legs-and-cleavage-again-4402951-PHO.html?seq=3

Pakistan's mysterious menace

Afghanistan: Not a pleasant prospect

LEADERS of the NATO-led alliance known as ISAF that is fighting in Afghanistan might be expected to be glad to see the back of President Hamid Karzai. The man whose government they have supported since 2001 is ineligible to stand in the election next April. Fickle and moody, Mr Karzai this week showed again just how ungrateful he can be. “The entire NATO exercise”, he told the BBC, “was one that caused Afghanistan a lot of suffering, a lot of loss of life, and no gains because the country is not secure.” Nearly 3,400 ISAF soldiers have been killed defending Mr Karzai’s government from its enemies. Western commanders were understandably indignant. Two factors, however, tempered their outrage. First, they know that when the West installed Mr Karzai, it saddled him with all the forms of democracy. Their man has therefore had to show that he is serving Afghans, not foreign generals. Second, after a frantic scramble for presidential candidates to register by October 6th, they know that in a year’s time they may be looking wistfully back on the Karzai era. Whoever succeeds him may be even harder to deal with, have a more dubious background and have achieved power by even murkier means than those that saw Mr Karzai “re-elected” in 2009. Mr Karzai will stand down in the year when ISAF is to withdraw its combat troops, leaving the Afghan army to carry on the fight against Taliban insurgents. The West is naturally anxious to leave behind a government that is capable of surviving and that has a semblance of democratic legitimacy. A president respected at home and abroad would certainly help. Some 27 candidates have registered, each with two vice-presidential running-mates in tow. Not all these men are warlords, and many will drop out. But enough are tribal strongmen with tainted records to cast a dark shadow over the entire field. Tickets often bridge ethnic divides, with at least one member of the largest group, the Pushtuns. One prominent candidate, Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, is credited with having invited al-Qaeda’s leadership to set up shop in Afghanistan. Another, Gul Agha Sherzai, is a warlord from Kandahar, once the stronghold of the (largely Pushtun) Taliban. He is nicknamed the “Bulldozer”—a tribute to his personal style as much as to his track record in seeing projects completed as governor of the province of Nangarhar. One vice-presidential candidate, Abdul Rashid Dostum, is a leader of the Uzbek minority and hence an important vote-winner, a role he performed for Mr Karzai in 2009. He was a military commander in the days of the Soviet-backed government that fell to the Taliban in 1994 and a warlord with a fearsome reputation. He is said by Western diplomats who have spent time with him recently to have mellowed. This is just as well, since he is on the ticket of one of the more cerebral candidates, Ashraf Ghani, who once called him a “known killer”. Mr Ghani is a former finance minister and World Bank official, and co-author of books, appropriately enough, on “fixing failed states” and “strategies for state-building”. Another of the more cosmopolitan candidates, Abdullah Abdullah, has similarly teamed up with two rougher diamonds. Mohammad Khan is a leader of the Hezb-i-Islami party, whose military wing is part of the insurgency fighting the government. Mohammad Mohaqiq, from the Hazara minority, has survived four recent attempts on his life. Like Mr Dostum, he was accused in a report last year by a human-rights watchdog of war crimes before 2001. Dr Abdullah, an ethnic Tajik (though with Pushtun blood), was foreign minister for the Northern Alliance, which, with American air and special-forces support, toppled the Taliban in 2001. He then emerged as an opposition leader and was runner-up in the fraudulent election in 2009. This election is unlikely to be much fairer. An article by Martine van Bijlert of the Afghan Analysts Network, a respected research group, lists the problems: a defective voter registry; millions of available voter cards not linked to voters; widespread insecurity; and “the collusion of electoral and security staff, whether prompted by loyalty, money or pressure, at all levels”. The sense that the state has the power to sway the election result gives great weight to any endorsement Mr Karzai might make. Yet he is likely to keep his promise not to offer one—at least openly—even though the field includes his older brother and a former foreign minister believed to be a favourite. Endorsement would taint the victory of “his” candidate; or, should the candidate lose, cause grave embarrassment to Mr Karzai. But he is not going away. A grand residence is under construction next to the presidential palace in Kabul. Mr Karzai says he wants to stay in the country and enjoy his “legacy”. Yet his presence may prove unhelpful, and his relations with his successor fraught. Design flaws Looking at the mess the election is likely to be, outsiders may be inclined to conclude that Afghans are not ready for democracy. Yet their political system was subverted from the outset by dubious choices made in 2001. For one, Mr Karzai himself has proved both weak and high-handed, and has tolerated scandalous corruption while always blaming foreigners. The new constitution gave Afghanistan its first-ever highly centralised government. Given the country’s ethnic and regional divides, that was a recipe for instability. In retrospect it was also a mistake to let into government warlords who had fought the Taliban but who were notorious for past abuses. And leaving even moderate elements of the Taliban outside the political process altogether led them to regroup as an insurgency. The steady escalation of the war might have happened anyway. But the exclusion of the Taliban made it inevitable. So the political structure agreed in 2001 never really gave peace, or democracy, a chance.The West will wince at next year’s election in Afghanistan; but it has itself to blame

Afghanistan: Logar governor killed in bomb blast at mosque

A bomb explosion killed the governor of central Logar province on Tuesday when he was delivering a speech to mark the first day of Eidul Adha, officials said.

At least 18 people suffered injuries in the bombing that took place at the main mosque in the provincial capital of Pul-i-Alam.

Crime branch police chief, Col. Mohammad Jan Abid, told Pajhwok Afghan News the bomb had been skillfully planted inside the microphone in the front part of the mosque.

Jamal, who assumed office six months ago, was delivering the speech to worshippers after offering Eid prayers, when the bomb went off, he said.

The governor’s spokesman, Din Mohammad Darwish, said the injured people were taken the main civil hospital in the city. Darwish said five of the wounded people were said to be in crucial condition.

A doctor at the hospital, Samiullah, said they had been delivered 16 injured people.

A witness, who declined to be named, said a spokesman for the provincial peace committee, Maulvi Sadiq, was also killed in the blast.

Jamal, 47, was a close confidant of President Hamid Karzai and served as his campaign manager during the 2009 presidential elections.

He also served as governor of eastern Khost province until he was appointed to his current post in Logar in April.

A high-profile target, he had survived a number of assassination attempts in the past, including with suicide bombings.

Jamal was recently in the spotlight following his revelation that a senior commander of the Pakistani Taliban was taken into custody by American forces in Logar province on Oct. 5.

US officials confirmed that Latif Mehsud, a leader of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, or TTP, was captured by US forces in a military operation.

No one immediately claimed responsibility for the attack.

A bomb explosion killed the governor of central Logar province on Tuesday when he was delivering a speech to mark the first day of Eidul Adha, officials said.

At least 18 people suffered injuries in the bombing that took place at the main mosque in the provincial capital of Pul-i-Alam.

Crime branch police chief, Col. Mohammad Jan Abid, told Pajhwok Afghan News the bomb had been skillfully planted inside the microphone in the front part of the mosque.

Jamal, who assumed office six months ago, was delivering the speech to worshippers after offering Eid prayers, when the bomb went off, he said.

The governor’s spokesman, Din Mohammad Darwish, said the injured people were taken the main civil hospital in the city. Darwish said five of the wounded people were said to be in crucial condition.

A doctor at the hospital, Samiullah, said they had been delivered 16 injured people.

A witness, who declined to be named, said a spokesman for the provincial peace committee, Maulvi Sadiq, was also killed in the blast.

Jamal, 47, was a close confidant of President Hamid Karzai and served as his campaign manager during the 2009 presidential elections.

He also served as governor of eastern Khost province until he was appointed to his current post in Logar in April.

A high-profile target, he had survived a number of assassination attempts in the past, including with suicide bombings.

Jamal was recently in the spotlight following his revelation that a senior commander of the Pakistani Taliban was taken into custody by American forces in Logar province on Oct. 5.

US officials confirmed that Latif Mehsud, a leader of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, or TTP, was captured by US forces in a military operation.

No one immediately claimed responsibility for the attack.

"پاکستانی حکومت قصداً زلزله ځپلو ته مرستې نه رسوي"

http://www.mashaalradio.com/

له پاکستانه خپرېدونکې په ډيلي ټايمز کې ليکوال مير محمد علي تالپور ليکي، د پاکستان حکومت په قصده د نړيوالو مرستندويه ادارو پر مخ د بلوچستان زلزله ځپلي ولس ته د مرستو رسولو لارې تړلې دي. ليکوال کاږي، د بلوچستان صوبې بې اختياره اعلی وزير عبدالمالک بلوڅ دوه وارې نړيوالو ادارو ته د مرستو له پاره خواست وکړ، خو له افتونو د ژغورنې د پاکستان قامي اداره يې پر وړاندې د غټ خنډ په توګه ولاړه ده. له ليکنې سره سم، ښاغلي بلوڅ په دغه لړ کې د پاکستان مرکزي حکومت ته رسمي مکتوب هم ولېږه، خو دغه اقدام يې کارګر ثابت نه شو. د ليکنې له مخې، له افتونو سره د مبارزې د پاکستان مرکزي ادارې د روانې مياشتې په ۸ مه نېټه د ملګرو ملتونو د مرستندويه ادارو د ګاډو هغه يوه کاروان په لاره کې ودراوه، چې له کراچۍ څخه د بلوچستان د آواران سيمې پر لور روان شوی وو. په ليکنه کې وړاندې ويل شوي، د پاکستان يادې ادارې منلي چې په بلوچستان کې د زلزلې له راتللو شپاړس ورځې وروسته هم دغه ناورين ځپليو خلکو ته مرستې نه دي رسول شوي. ليکنه کاږي، پاکستانی ايسټيبلشمنټ غواړي، د آواران د خلکو پر مخ د مرستو بندولو له لارې د دوئ مورال کمزوری کړي، او زياتوي چې په دې ترڅ کې د پاکستان حکومت د بشريت پر ضد د جرم مرتکب کيږي. په ليکنه کې راغلي، د پاکستان امنيتي ځواکونه چې کله د صوبې زلزله ځپليو خلکو ته مرستې ورکوي نو ورته وايي چې د (پاکستان زنده باد) شعارونه ورکړي. د ليکوال په اند، د مرستو تر لاسه کولو له پاره دا رقم شرطونو د زلزله ځپليو خلکو عزت نفس مجروح کوي. د ليکنې له مخې، د پاکستان پوځ د آواران خلکو ته باور ورکول غواړي چې که دوئ غواړي د ښې ورځې خاوندان شي نو بايد له پوځ سره يو ځای شي او د بلوڅ بيلتون خوښو وسله والو ډلو له ملاتړ څخه لاس واخلي. د ليکوال په وينا، د پاکستان پوځ ډېره په اسانۍ سره دا خبره هېروي چې د بلوچستان د حالت خرابولو زمه واري پر بيلتون خوښو بلوڅانو نه، بلکې د دې هېواد پر پاليسي جوړونکو ادارو راځي. ليکوال زياتوي، د پاکستان حکومت د تېرو ۶۵ کلونو په موده کې يوازې د بلوچستان وسايل په نظر کې ساتلي او د خلکو يې د ښېګڼې چارې له پامه غورځولې دي.

Malala: ''Pakistan’s (almost) Nobel laureate''

http://afpak.foreignpolicy.com/

By Ziad Haider

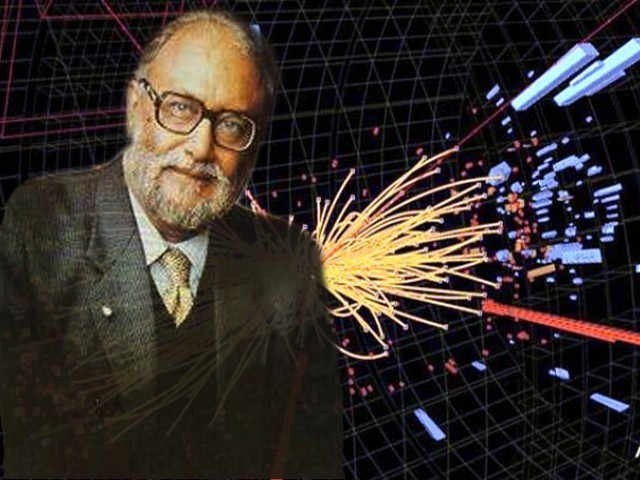

On Friday, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, passing over a remarkable top contender: Malala Yousafzai, a 16-year-old girl from Pakistan who was shot in the head by the Taliban last year for speaking out about girls' education. Instead of falling silent, Yousafzai's voice has only grown louder since the attack. She continues to champion her cause for a land to which she cannot return; the Taliban renewed their death threats against her this week. While she is surrounded by well-wishers on her current visit to the United States, perhaps no one can share her sense of acclaim and exclusion as well as Pakistan's (still) only Nobel laureate, Dr. Abdus Salam. Salam was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1979 for his work on characterizing what is now known as the Higgs boson particle. Coincidentally, this year the Nobel Prize in Physics was shared by Peter Higgs, after whom the particle is named. Dubbed the "God particle," the Higgs boson is viewed as a potential building block of the universe. While some of Salam's critics might have cried heresy at his work, they instead chose to do so about his faith. For just as Malala's mistake was being a girl, Salam's was being a member of the Ahmadi sect - a religious group declared to be non-Muslims in a 1974 constitutional amendment. After the amendment passed, Salam resigned from his government post. A Nobel prize five years later engendered no rapturous embrace upon his return home. Pakistan's leaders chose to keep him at arm's length. Even the word "Muslim" in the "first Muslim Nobel laureate" engraved on his tombstone is painted over. His colleagues continue to speak with equal wonder of his work and sadness for his treatment. It is one of the many contradictions of Pakistan that the very town, Jhang, which produced a man of Salam's learning -- one who sought to unlock the secrets of the cosmos -- now produces parochial militancy. A militancy that has metastasized like a cancer in Pakistan and now consumes its children. When she first heard of the Taliban's threats against her, Yousafzai feared not for her own safety but for her father's. In a recent interview on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart she said that she thought the Taliban would never stoop to attacking a young girl. She was wrong. To be sure, many Pakistanis are ambivalent about Yousafzai. In an environment rampant with anti-American sentiment and conspiracy theories, some view praise for her a way of shaming Pakistan. Others question the degree of attention merited to one individual when over 5,000 lives have reportedly been lost to terrorism over the past five years. Weariness with the West's fascination with the latest "victim" from Pakistan has also emerged. A few years ago, for instance, U.S. media outlets were abuzz with stories about another Pakistani woman who had been brutally raped and had similarly channeled her tragedy into championing women's rights. Such cynicism, however, is of less import than the pernicious politics of exclusion in Pakistan -- a politics whereby one segment of society fervently believes it has a monopoly over deen (faith) and duniya (world). At best, the other is inferior; at worst, he or she merits elimination. It's an exclusionary system whereby individuals as different as a physicist and a teenage girl continue to be pushed outside society's bounds - either by force or by law. Nobel laureates, usually feted in other countries, seem strangely destined to be banished in Pakistan. Much ink has been spilt on Pakistan's troubles, which seem to know no end. Yet the same country produced a young girl who is optimistically forging ahead, despite the horror she has experienced. Malala Yousafzai channels Pakistan's remarkable resilience. That she did not win the Nobel Peace Prize is thus ultimately irrelevant. What really matters is when can she go home.For just as Malala's mistake was being a girl, Salam's was being a member of the Ahmadi sect - a religious group declared to be non-Muslims in a 1974 constitutional amendment.

Practical steps: HRCP on Balochistan

HRCP report on Balochistan

How the Tea Party broke the Constitution

By Timothy B. Lee

Tea Partiers are the most enthusiastic advocates of America's system of government, with its divided powers, checks and balances and representative government. So it's ironic that their innovative organizing techniques have revealed a major weakness in America's system of government.

Republican members of Congress feel intense pressure from tea party activists to stick to a principled conservative agenda. Any deviation from the conservative line is met with a flood of phone calls and a credible threat of a primary challenge.

But Democrats control the Senate and the White House. They're not interested in signing onto the tea party's conservative agenda. And traditionally, this kind of standoff has been resolved by compromise. Leaders from both sides would negotiate a compromise and then sell it to their members.

But largely thanks to the tea party, House Speaker John Boehner doesn't have much leverage over his members. He can't credibly offer to compromise with President Obama. As Obama has realized that, he has become less and less willing to compromise himself, leading to the current standoff.

No compromise

Our system of divided powers often requires negotiation. And negotiation works best when all parties don't just think about the present, but also the future. Good negotiators want to get the best deal they can today, but they also try to build a relationship that will make it easier to reach the next deal. That means being willing to meet the other party halfway and looking for deals that are good for both sides.

But what do you do when you offer concessions and the other party doesn't reciprocate? For the past two and a half years, Barack Obama has faced this dilemma. He has offered concessions to help reach agreement with Republican leaders, but they haven't reciprocated. To the contrary, each time Democrats have agreed to cut spending, House Republicans have used the new figure as a new baseline for the next round of negotiation.

In 2011, Democrats agreed to $39 billion in cuts (in one fiscal year) to avert a government shutdown. A few months later, they agreed to an additional $2.1 trillion in cuts (over 10 years) as part of a deal to raise the debt ceiling.

The majority of those cuts took the form of across-the-board "sequestration"— indiscriminate cuts to virtually all discretionary programs. A "supercommittee" was supposed to come up with a more sensible package of cuts. But negotiations failed, so spending cuts were due to kick in at the start of 2013. A last-minute deal in January delayed those cuts until March, but the parties couldn't agree on a plan to replace them.

The result of all this cutting is that, adjusted for inflation, discretionary spending levels have fallen dramatically in the past three years:

The new, lower level of spending then became the Democratic position in the latest round of negotiations. House Republicans wanted spending to stay at the lower post-sequester levels and they wanted to delay Obamacare by a year.

Meanwhile, Republicans have not given an inch on Democrats' desires for higher tax revenue. Taxes did go up for high earners at the start of 2013, but that increase was scheduled by Congress more than a decade ago. Republicans have steadfastly opposed any other proposals to increase tax revenue.

And despite Democrats' flexibility, there seems to be no end in sight for the Republicans' strategy of perpetual brinksmanship. So far, the GOP has tried to use the threat of shutdown or default to extract policy concessions in March 2011, August 2011, February 2013, March 2013 and now October 2013. There's every reason to think that if Obama had made more concessions last month to avert a shutdown, Republicans would have come back for even more in 2014.

In short, Obama is negotiating with a party that always demands further concessions and is never willing to reciprocate. After a certain number of rounds of this, any rational negotiator is going to dig in his heels and refuse to give more ground.

Short-term thinking

In a narrow sense, the Republican strategy has been a success, cutting hundreds of billions of dollars from the discretionary budget. But it has two big flaws. The obvious one is that Obama finally called Republicans' bluff and allowed the government to shut down, and the public has overwhelmingly blamed the GOP, which could damage the party's prospects in future elections.

But the more subtle problem with the strategy is that brinksmanship over the discretionary budget is unlikely to fix America's long-term fiscal problems. Those problems are largely caused by the growing cost of entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security. These "mandatory" programs aren't subject to annual appropriations, so brinksmanship over appropriations bills isn't likely to change them.

In past negotiations, Obama has signaled a willingness to accept some cuts to entitlement programs, but only as part of a "balanced" package that includes some tax increases.

A rational Republican leader would have recognized some time ago that it's in the long-term interest of the Republican Party and the conservative movement (not to mention the country) to cut a deal with the president in which conservatives get some of their long-term policy priorities in exchange for giving Democrats some of theirs. Such a deal would help to burnish the party's image while making possible long-term fiscal reforms that they can't get by manufacturing a new crisis every few months.

The tea party problem

So why hasn't John Boehner done that? Because the tea party has emasculated the nominal leaders of the House Republican caucus. Boehner has so little control over his members that he can't credibly offer Democrats significant policy concessions.

Boehner's impotence was vividly illustrated last December, when Congress was debating how to deal with the automatic tax hikes that were scheduled to take effect at the start of 2013. Boehner tried to pass a bill, known as "Plan B," to cancel scheduled tax hikes for everyone making less than a million dollars. He believed that the move would strengthen his hand in negotiations with the White House, which only wanted to cancel the tax hike for families making more than $250,000.

But tea party activists portrayed Boehner's legislation as a tax hike, and helped defeat it. That left him with little leverage in subsequent negotiations, since Democrats could get the upper-bracket tax hikes they wanted without lifting a finger. So a few days later, Republicans were forced to accept a deal that canceled the tax increase only for families making $450,000 — a worse outcome from the tea party's perspective.

So why does the tea party have so much power? A big reason is the threat of primary challenges. As The Post reported at the time, "several senior GOP aides said that many of the Republicans were wary of voting for Plan B" because it would draw a primary challenger who would portray it as a vote to raise taxes.

Another factor has been the abolition of earmarks, a reform pushed by tea party activists. In the past, leadership could withhold earmarks from members of their caucus who refused to vote the party line. Now that source of leverage is gone.

As a result, Boehner can't credibly offer significant concessions in negotiations with Democrats. He can't credibly offer higher taxes in exchange for spending cuts because grass-roots tea party activists will be able to intimidate many of his caucus members into voting against them. He can't even promise an end to brinksmanship, because the same grass-roots outrage that has forced him into a confrontational posture in the past will probably do so again in the future.

In a sense, the tea party has made the Republican party the most democratic political party American politics has ever seen. Grass-roots activists exercise more power over the decisions of congressional Republicans than ever before.

Unfortunately, this is proving self-destructive. A party that's effectively leaderless can't formulate a coherent plan and execute it. That leads to a confused political strategy and, even worse, an incoherent policy agenda.

And in our system of government, a dysfunctional Republican Party can easily produce a dysfunctional government. Divided government requires compromise to function. And compromise can only happen if congressional leaders can credibly negotiate on behalf of their caucuses.

Tea party activists like to emphasize that we're a constitutional republic, not a direct democracy. Some have even called for the repeal of the 17th Amendment that established the direct election of senators. Returning to a Senate elected by state legislatures would probably be overkill, but the tea party is right that our system of government depends on elected representatives being somewhat insulated from the day-to-day passions of the people who elected them.

The tea party's rapid-response activism and the constant threat of primary challenges has made it difficult for Republican members of Congress to exercise the kind of independent judgement the Founders envisioned. That is producing a kind of slow-motion constitutional crisis, as our elected leaders find it harder and harder to reach the compromises necessary to keep the system functioning.

By Timothy B. Lee

Tea Partiers are the most enthusiastic advocates of America's system of government, with its divided powers, checks and balances and representative government. So it's ironic that their innovative organizing techniques have revealed a major weakness in America's system of government.

Republican members of Congress feel intense pressure from tea party activists to stick to a principled conservative agenda. Any deviation from the conservative line is met with a flood of phone calls and a credible threat of a primary challenge.

But Democrats control the Senate and the White House. They're not interested in signing onto the tea party's conservative agenda. And traditionally, this kind of standoff has been resolved by compromise. Leaders from both sides would negotiate a compromise and then sell it to their members.

But largely thanks to the tea party, House Speaker John Boehner doesn't have much leverage over his members. He can't credibly offer to compromise with President Obama. As Obama has realized that, he has become less and less willing to compromise himself, leading to the current standoff.

No compromise

Our system of divided powers often requires negotiation. And negotiation works best when all parties don't just think about the present, but also the future. Good negotiators want to get the best deal they can today, but they also try to build a relationship that will make it easier to reach the next deal. That means being willing to meet the other party halfway and looking for deals that are good for both sides.

But what do you do when you offer concessions and the other party doesn't reciprocate? For the past two and a half years, Barack Obama has faced this dilemma. He has offered concessions to help reach agreement with Republican leaders, but they haven't reciprocated. To the contrary, each time Democrats have agreed to cut spending, House Republicans have used the new figure as a new baseline for the next round of negotiation.

In 2011, Democrats agreed to $39 billion in cuts (in one fiscal year) to avert a government shutdown. A few months later, they agreed to an additional $2.1 trillion in cuts (over 10 years) as part of a deal to raise the debt ceiling.

The majority of those cuts took the form of across-the-board "sequestration"— indiscriminate cuts to virtually all discretionary programs. A "supercommittee" was supposed to come up with a more sensible package of cuts. But negotiations failed, so spending cuts were due to kick in at the start of 2013. A last-minute deal in January delayed those cuts until March, but the parties couldn't agree on a plan to replace them.

The result of all this cutting is that, adjusted for inflation, discretionary spending levels have fallen dramatically in the past three years:

The new, lower level of spending then became the Democratic position in the latest round of negotiations. House Republicans wanted spending to stay at the lower post-sequester levels and they wanted to delay Obamacare by a year.

Meanwhile, Republicans have not given an inch on Democrats' desires for higher tax revenue. Taxes did go up for high earners at the start of 2013, but that increase was scheduled by Congress more than a decade ago. Republicans have steadfastly opposed any other proposals to increase tax revenue.

And despite Democrats' flexibility, there seems to be no end in sight for the Republicans' strategy of perpetual brinksmanship. So far, the GOP has tried to use the threat of shutdown or default to extract policy concessions in March 2011, August 2011, February 2013, March 2013 and now October 2013. There's every reason to think that if Obama had made more concessions last month to avert a shutdown, Republicans would have come back for even more in 2014.

In short, Obama is negotiating with a party that always demands further concessions and is never willing to reciprocate. After a certain number of rounds of this, any rational negotiator is going to dig in his heels and refuse to give more ground.

Short-term thinking

In a narrow sense, the Republican strategy has been a success, cutting hundreds of billions of dollars from the discretionary budget. But it has two big flaws. The obvious one is that Obama finally called Republicans' bluff and allowed the government to shut down, and the public has overwhelmingly blamed the GOP, which could damage the party's prospects in future elections.

But the more subtle problem with the strategy is that brinksmanship over the discretionary budget is unlikely to fix America's long-term fiscal problems. Those problems are largely caused by the growing cost of entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security. These "mandatory" programs aren't subject to annual appropriations, so brinksmanship over appropriations bills isn't likely to change them.

In past negotiations, Obama has signaled a willingness to accept some cuts to entitlement programs, but only as part of a "balanced" package that includes some tax increases.

A rational Republican leader would have recognized some time ago that it's in the long-term interest of the Republican Party and the conservative movement (not to mention the country) to cut a deal with the president in which conservatives get some of their long-term policy priorities in exchange for giving Democrats some of theirs. Such a deal would help to burnish the party's image while making possible long-term fiscal reforms that they can't get by manufacturing a new crisis every few months.

The tea party problem

So why hasn't John Boehner done that? Because the tea party has emasculated the nominal leaders of the House Republican caucus. Boehner has so little control over his members that he can't credibly offer Democrats significant policy concessions.

Boehner's impotence was vividly illustrated last December, when Congress was debating how to deal with the automatic tax hikes that were scheduled to take effect at the start of 2013. Boehner tried to pass a bill, known as "Plan B," to cancel scheduled tax hikes for everyone making less than a million dollars. He believed that the move would strengthen his hand in negotiations with the White House, which only wanted to cancel the tax hike for families making more than $250,000.

But tea party activists portrayed Boehner's legislation as a tax hike, and helped defeat it. That left him with little leverage in subsequent negotiations, since Democrats could get the upper-bracket tax hikes they wanted without lifting a finger. So a few days later, Republicans were forced to accept a deal that canceled the tax increase only for families making $450,000 — a worse outcome from the tea party's perspective.

So why does the tea party have so much power? A big reason is the threat of primary challenges. As The Post reported at the time, "several senior GOP aides said that many of the Republicans were wary of voting for Plan B" because it would draw a primary challenger who would portray it as a vote to raise taxes.

Another factor has been the abolition of earmarks, a reform pushed by tea party activists. In the past, leadership could withhold earmarks from members of their caucus who refused to vote the party line. Now that source of leverage is gone.

As a result, Boehner can't credibly offer significant concessions in negotiations with Democrats. He can't credibly offer higher taxes in exchange for spending cuts because grass-roots tea party activists will be able to intimidate many of his caucus members into voting against them. He can't even promise an end to brinksmanship, because the same grass-roots outrage that has forced him into a confrontational posture in the past will probably do so again in the future.

In a sense, the tea party has made the Republican party the most democratic political party American politics has ever seen. Grass-roots activists exercise more power over the decisions of congressional Republicans than ever before.

Unfortunately, this is proving self-destructive. A party that's effectively leaderless can't formulate a coherent plan and execute it. That leads to a confused political strategy and, even worse, an incoherent policy agenda.

And in our system of government, a dysfunctional Republican Party can easily produce a dysfunctional government. Divided government requires compromise to function. And compromise can only happen if congressional leaders can credibly negotiate on behalf of their caucuses.

Tea party activists like to emphasize that we're a constitutional republic, not a direct democracy. Some have even called for the repeal of the 17th Amendment that established the direct election of senators. Returning to a Senate elected by state legislatures would probably be overkill, but the tea party is right that our system of government depends on elected representatives being somewhat insulated from the day-to-day passions of the people who elected them.

The tea party's rapid-response activism and the constant threat of primary challenges has made it difficult for Republican members of Congress to exercise the kind of independent judgement the Founders envisioned. That is producing a kind of slow-motion constitutional crisis, as our elected leaders find it harder and harder to reach the compromises necessary to keep the system functioning.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)