M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Syrian president visits Russia’s Khmeymim airbase

President Bashar Assad visited Russia’s airbase at Khmeymim and familiarized himself with new weaponry, in particular, the Su-35 fighter jet, the Russian defense ministry’s press service said on Tuesday.

While visiting the base, the Syrian president met with Russian Chief of Staff Valery Gerasimov.

"While walking about the Khmeymim airbase, President Bashar Assad familiarized himself with the Russian Su-35 fighter jet and other state-of-the-art weapons," the ministry said.

The chief of the Russian General Staff and the Syrian president have discussed the coordination of efforts in the fight against the Islamic State (IS) and Jabhat al-Nusra terror groups (outlawed in Russia), according to the ministry.

More:

http://tass.com/world/953551

China strives to reconcile Kabul, Islamabad

Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi visited Afghanistan and Pakistan over the weekend, and a trilateral joint statement was signed, which brought hope of relieving Afghanistan-Pakistan tension. According to a joint statement, the three parties agreed to establish the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan Foreign Ministers' dialogue mechanism and Afghanistan and Pakistan agreed to establish a crisis management mechanism. These steps will be of significance to stabilize South Asia and strengthen China's cooperation with Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The two countries, both plagued by terrorism, enjoy a good relationship with China. But the Kabul-Islamabad relationship is periodically interrupted by border disputes and suspicion of the other side's support of terrorism.

The military action launched by the US in Afghanistan in 2001 aimed to root out terrorism, but far from achieving this goal, it instead opened up a Pandora's Box. Without a complete plan to cope with the post-war situation, Washington started to withdraw troops from the country. Now the 8,000-plus American soldiers currently stationed in Afghanistan are not very helpful in stabilizing the situation.

New Delhi has strengthened its relationship with Kabul in recent years as India is pursuing its geopolitical interests in the region. But it is doing so more out of a desire to contain Pakistan, and has little effect in addressing the Afghanistan-Pakistan feud.

China is not willing to intervene in peripheral countries' internal affairs, and is especially cautious of any involvement in political conundrums of countries where the US has troops stationed. This time, Afghanistan and Pakistan have brought the request to China, and Beijing, under this situation, has reached out to help mediate.

Stability and the maintenance of normal relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan conform to China's interests, and will contribute to the Belt and Road initiative. Minister Wang's two-day trip has helped establish a crisis management mechanism and the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan Foreign Ministers' dialogue mechanism, and apparently, the latter mechanism will play a significant role in consolidating the former. This is an encouraging start.

There are no quick fixes for the issue. Apart from dispelling misunderstandings and alleviating conflicts of interest, Afghanistan and Pakistan need to stabilize their domestic situations to back their reconciliation. This is not easy. After all, China cannot shape a peaceful, stable and mutually friendly Afghanistan-Pakistan relationship all by itself without efforts from the two countries.

But China is striving for this end. Beijing hopes for peace and prosperity of peripheral countries, and has more resources and influence to promote regional cooperation than before. The Chinese government and society sincerely hope that Afghanistan and Pakistan can overcome the aftereffects of past periods of unrest and catch up with the times. China will continue to be a reliable partner to the two countries in this process.

The two countries, both plagued by terrorism, enjoy a good relationship with China. But the Kabul-Islamabad relationship is periodically interrupted by border disputes and suspicion of the other side's support of terrorism.

The military action launched by the US in Afghanistan in 2001 aimed to root out terrorism, but far from achieving this goal, it instead opened up a Pandora's Box. Without a complete plan to cope with the post-war situation, Washington started to withdraw troops from the country. Now the 8,000-plus American soldiers currently stationed in Afghanistan are not very helpful in stabilizing the situation.

New Delhi has strengthened its relationship with Kabul in recent years as India is pursuing its geopolitical interests in the region. But it is doing so more out of a desire to contain Pakistan, and has little effect in addressing the Afghanistan-Pakistan feud.

China is not willing to intervene in peripheral countries' internal affairs, and is especially cautious of any involvement in political conundrums of countries where the US has troops stationed. This time, Afghanistan and Pakistan have brought the request to China, and Beijing, under this situation, has reached out to help mediate.

Stability and the maintenance of normal relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan conform to China's interests, and will contribute to the Belt and Road initiative. Minister Wang's two-day trip has helped establish a crisis management mechanism and the China-Afghanistan-Pakistan Foreign Ministers' dialogue mechanism, and apparently, the latter mechanism will play a significant role in consolidating the former. This is an encouraging start.

There are no quick fixes for the issue. Apart from dispelling misunderstandings and alleviating conflicts of interest, Afghanistan and Pakistan need to stabilize their domestic situations to back their reconciliation. This is not easy. After all, China cannot shape a peaceful, stable and mutually friendly Afghanistan-Pakistan relationship all by itself without efforts from the two countries.

But China is striving for this end. Beijing hopes for peace and prosperity of peripheral countries, and has more resources and influence to promote regional cooperation than before. The Chinese government and society sincerely hope that Afghanistan and Pakistan can overcome the aftereffects of past periods of unrest and catch up with the times. China will continue to be a reliable partner to the two countries in this process.

Can There Be Peace With Honor in Afghanistan?

BY LAWRENCE FREEDMAN

Over the next few weeks, U.S. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis is due to provide President Donald Trump with a new strategy for Afghanistan. This will be the latest in a long series, produced on a regular basis since 2001, all with the core objective of preventing the country reverting to a sanctuary for terrorism. Mattis cannot be accused of ramping up expectations for the new approach he is seeking to develop. He describes the current situation as a stalemate, but with the balance having swung to the Taliban. Reversing this, he argues, will require more troops to help develop Afghan capabilities. When asked what it would mean to win, he says violence must be brought down to a level where it could be managed by the Afghan government without it posing a mortal threat.

There are several obstacles to even this modest definition of victory. First, it envisions an Afghan government able to competently deal with groups such as al Qaeda without outside assistance; it envisions, in other words, a government very different than the one Afghanistan has had for some time. Another obstacle is posed by the supporters of the former Taliban government, who are well embedded in Afghanistan and have sympathetic backers in Pakistan. Regardless of the strategy Mattis settles on, the war offers little prospect for a stable end-state in which the Afghan government will be able to think about issues other than security, or U.S. forces can withdraw without having to rush back to repair the damage as the Taliban surge once more.

But Afghanistan is not unique in this regard. The situation in Iraq is similar, as are the wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Libya, Ukraine, and any number of other international conflicts. We have entered an era of wars that wax and wane in intensity, and at best become manageable, rather than end with ceremonies to conclude hostilities. The challenge posed to traditional notions of war by these endless conflicts has been the subject of much debate. What is long overdue is reflection on the challenge posed to our definition of peace.

Once upon a time the distinction between war and peace was clear-cut. Peace ended when war was declared. Almost immediately acts which had previously been considered criminal, harmful and obnoxious became legal and desirable. Trade would be blocked and aliens interned. Neutrals had to pay attention. Eventually the war would end when a treaty was signed, setting the terms for a new peace. The fighting would stop, trade would resume and aliens would be released. Neutrals could get on with their business. As the previous peace had been flawed, for it had ended with war, the new peace must address those flaws. In addition, as wars involve sacrifices and pain, the new peace must provide a degree of reward and compensation. It must represent progress. It has been a long time since we enjoyed such clarity. Wars are no longer declared. The trend began in the 1930s, including the use of euphemisms for war, as those states which had renounced war as an instrument of national policy (the language of the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact) embarked on invasions. The trend was set by the Manchurian Incident of 1931, when Japan invaded China. The Second World War involved lots of declarations, but few wars have been declared since. In those many contemporary wars that involve civil conflict, formal declarations are obviously irrelevant. Cease-fires and peace settlements are regular but they have a habit of not sticking. Meanwhile, international wars now frequently conclude with no more than a cease-fire agreement (as with Korea in 1953 or Iraq in 1991), explicitly leaving open the possibility that they can resume at a later date.

So, warfare has become less of a separate, marked-off activity, demarcated in time and space, and instead a messy condition, marked by violence, found within and between states. It can involve examples of force that are intense but localized or else widespread and sporadic. Borders have become permeable, so that neighbors move in and out while denying that they are engaged in anything so blatant as aggression. The absence of large-scale hostilities at any particular moment in any particular region does not mean that peace has broken out because they are often on the edge of war. A true peace needs to be for the long-term, with disputes resolved and relations getting closer — not a pause to allow for restocking and some recuperation before the struggle continues.

As the line between peace and war has become blurred, international relations scholars have used a simple measure of 1,000 battle deaths in a given year to mark when the line is crossed into war. A conflict with fewer battle deaths, then, for analytical purposes is not a war but merely a militarized inter-state dispute. With civil wars the threshold is much lower in the key databases than inter-state wars, so fighting can sneak below the required level but then sneak up again. Over long periods countries, such as Afghanistan or Iraq, can experience many different sorts of violence without ever enjoying a lengthy period of tranquility that might deserve to be known as peace. The literature now refers to “war prevention” and “war termination” without requiring any references to the “peace” being left or to which it is hoped to return. There are still “peacekeeping” missions, meant to sustain a tentative peace, but when these missions have been sent into situations without any peace to keep the term has proved clearly inadequate. Some variations were attempted to recognize this difficulty – such as “‘peace enforcement” or “peace support” — until it was accepted that a durable peace might prove to be elusive and so instead the designation became “stabilization operations.”

When a war was undertaken for purposes of conquest then success could be measured in terms of territory gained or held. But conquest, pure and simple, is no longer represented as a legitimate objective of war, even when territory is being seized. The old imperialism was also often presented as a civilizing process, and not just about plunder and exploitation. Once the empires were dismantled after 1945 there was no appetite to construct anything comparable. Instead help with “state-building” is offered. “Victory,” for which Gen. Douglas MacArthur told us there is no substitute, is another word that has fallen out of fashion, except when talking about a specific battle. President George W. Bush tried “mission accomplished” in Iraq, but it turned out that it wasn’t. When describing a desirable situation these days ‘order’ is used as much as peace.The concept of peace has become a notable absentee in contemporary strategic discourse. Even university departments of “peace studies” spend a lot of time talking about conflict and violence and how to stop it. Those working in this tradition are heirs to the idealism that saw war as unnatural and representing the worst of human nature and national conceits. They continue to oppose militarism and its representations in mainstream thinking. But even within this tradition there has always been a tension between those who are essentially pacifists, so that any violence is retrograde, and those who believe that war can only be banished through the defeat of injustice and the promotion of freedom. On the one hand is the absence of war, the negative peace when hatreds may still simmer and repression may be rife; on the other the more positive peace, which might require taking sides once fighting has begun.

The importance of this distinction is that when we do get around to discussing peace it is largely in positive terms. Peace must be “just and lasting.” A coming peace is rarely described in terms that acknowledge the challenges facing war-torn societies as they attempt to recover and reform. The promise, once the “evil-doers” are defeated, is of freedom and democracy flourishing, bringing with them prosperity and social harmony. Even when intervening in societies whose future we cannot (and should not) control the West is reluctant to say that we have done little more than calm things down and made things less bad than they might have been. It is difficult to justify the lives lost and the expenses incurred in the most discretionary intervention by proclaiming a so-so result. Indeed, the temptation is to cover the promised outcome with the full rhetorical sugar-coating. Looking back at the claims made about what could be achieved in Afghanistan and Iraq, the ambition is extraordinary: terrorism defeated, a fearful ideology discredited, whole regions turned toward the path of democracy and away from dictatorship, an end to the drug trade, and so on.

Yet we know, and have been reminded, that the brutality and violence associated with war is not a natural route to a good peace. War leaves its legacy in grieving, division, and bitterness, in shattered infrastructure, routine crime, and displaced populations vulnerable to hunger and disease. There were “good peaces” achieved after 1945 with both Germany and Japan (which is why the wars that led to their defeat were considered unambiguously good). But these required more than military victory. They also demanded the commitment of a considerable amount of civilian planning and resources that would have been quickly lost if the Cold War had ever turned hot.

The astonishing feature of the invasion of Iraq was the refusal to put any effort into what was described as the “aftermath” of the occupation, and the complete lack of preparedness to take advantage of whatever opportunities for a better society that might have been created. If we look back at policy failures here and elsewhere they often lie in the reluctance to make the effort and deploy the resources to address the long-term issues of reconstruction once fighting subsides. In short, there has been no agreed view about the demands of peace.

Thucydides’s observation that wars are undertaken for reasons of “fear, honor, and interest” has been quoted by members of the Trump administration. These three words allow for a wealth of interpretation and all can be said to be in play when dealing with the Islamic State or Afghanistan. Of the three, doing justice to fear would require not only the elimination of terrorist sanctuaries in the respective countries, which might be possible, but preventing their return, which seems optimistic. Securing American interests might require the establishment of states that are more stable, and societies that are more free, and less sectarian, internally violent, and corrupt. These are individually matters of degree and also do not come as a package. The tension between social order and individual freedom runs through political theory as well as Western foreign policy and is no closer to resolution. Even the best likely outcomes now will feel unsatisfactory even if further calamities can be avoided. Which leaves honor as the final path to peace. This is the simplest to achieve as all it requires is acting in a principled way with high standards. It does not preclude a disappointing material outcome. Indeed, when we think of peace with honor, two great failures that come to mind. In 1938 this is what British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain claimed to have achieved when he came back from Munich after meeting with Hitler, as did U.S. President Richard Nixon when talking about the Paris Peace Accords at the start of 1973. Honor means you did what you could, not that you achieved what you set out to achieve.

We talk about peace as a utopian condition, as a set of desiderata for a better world to keep us motivated when times are tough, or when inquiring into the requirements of postwar reconstruction. But the nature of the peace we seek needs to be integrated as a matter of course into any military strategy, and in contemporary conditions requires a renewed commitment to realism. There is no point in describing an attractive future if there is no obvious way to reach it. Military planners should remember that the conduct of a war, as well as the cause for which it is fought, shapes any eventual peace. Opportunities need to be taken to consider what might seriously be achieved through the use of force, nonviolent alternatives that might achieve comparable objectives, and also what can be done with a war that others have started but we wish to see finished.

Si vis pacem, para bellum. “If you want peace, prepare for war,” goes the Roman adage. But if you prepare for war then at least think about the peace you want.

Pakistan: Balochistan, The Chinese Chequered – Analysis

By Tushar Ranjan Mohanty

The Islamic State (IS, also Daesh) on June 8, 2017, claimed the killing of two Chinese nationals who had been abducted from the Jinnah Town area of Quetta, the provincial capital of Balochistan, in the afternoon of May 24, 2017. Amaq, the IS propaganda agency, declared, “Islamic State fighters killed two Chinese people they had been holding in Baluchistan province, south-west Pakistan.” The Chinese couple, Lee Zing Yang (24) and Meng Li Si (26), were studying Urdu in Quetta, where they reportedly also ran a Mandarin language course.According to Deputy Inspector General Police Aitzaz Goraya, unknown abductors, wearing Police uniforms, had forced the two foreigners into a vehicle at gunpoint and driven away. They also tried to overpower another Chinese woman but she ran away. A man present at the site attempted to resist the kidnapping, but was shot at by one of the abductors. So far no local group has claimed responsibility for the incident (abduction and subsequent killing). Reports speculate that the actual perpetrators were linked to the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi al Alami (LeJ-A), the international wing of the LeJ, which believed to be affiliated to Daesh.

The claim came hours after Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) released details of a three-day operation (June 1-3) by the Pakistan Army against Daesh-affiliated terrorists in the Mastung area of Balochistan, in which Security Forces (SFs) had killed 12 suspected terrorists, including two suicide bombers. ISPR claimed, There were reports of 10-15 terrorists of a banned outfit Lashrake-Jhangivi Al-Almi (LeJA) hiding in caves near Isplingi ( Koh-i-Siah/Koh-i- Maran) 36 Kilometer South East of Mastung.” And further, “The suicide bomber used against Deputy Chairman of Senate Maulana Abdul Ghafoor Haydri on May 12 was also sent by [the targeted group].” The ISPR statement asserted that SFs destroyed an explosives facility inside the cave where the terrorists were hiding, and recovered a cache of arms and ammunition, including 50 kilogrammes of explosives, three suicide jackets, 18 grenades, six rocket launchers, four light machine guns,18 small machine guns, four sniper rifles, 38 communication sets and ammunition of various types.

Pakistan initially denied the Chinese couple’s death, perhaps due to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s presence, alongside Chinese President Xi Jinping, at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit in Astana on June 9, 2017. The first reaction from Pakistani authorities came four days after the Daesh claim. On June 12, 2017, Federal Minister of the Interior Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan confirmed that two Chinese nationals who had been abducted from Quetta had been killed.

The killing of the Chinese couple has underscored questions about the security of Chinese workers in Pakistan, and the country’s centrality to China’s ambitious One Belt One Road (OBOR) Initiative. The centrepiece of the ‘new Silk Route’ plan, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), passes through insurgency-hit Balochistan. Earlier, on May 31, 2017, amid Beijing’s growing concerns about the safety of two of its abducted nationals, the National Security Committee, presided over by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, reviewed the security of CPEC and Chinese nationals based in Pakistan. The NSC meeting released a press statement which gave no details, but noted that “security for CPEC projects also came under discussion”.

On June 3, 2017, 11 Chinese nationals— three men and eight women — living in the Jinnah Town of the Quetta were shifted to Karachi, and then flown back to China. Abdul Razzaq Cheema, Quetta’s Regional Police Officer, stated that these Chinese nationals had been living in Quetta for almost a year, and that two South Korean families had also been living in Quetta’s Jinnah Town for four years. After the abduction of the two Chinese nationals, Police had increased security of Chinese and other foreign nationals working on different component projects of CPEC, as well as with NGOs and United Nations’ organisations in Quetta and other parts of Balochistan.

The complex, multilayered, seemingly never-ending security crisis in Balochistan appears more dangerous with the entry of Daesh onto the scene. Balochistan has been under attack by separatists, insurgents, and Islamist terrorists for over a decade, and the situation can only worsen with Daesh’s entry. The Government, however, continues to deny Daesh’s existence in the Province and, most recently, on June 13, 2017, Balochistan Home Minister Mir Sarfaraz Bugti insisted that the group had no presence in the Province.

While the abduction and killing of the Chinese nationals was clearly a security failure, Pakistan has given the crime a religious angle, diverting attention from issues relating to ongoing CPEC projects in insurgency-hit Balochistan. Thus, on June 12, 2017, Federal Minister of the Interior Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan claimed that the slain Chinese couple belonged to a group of Chinese people who had obtained a business visa for Pakistan but were engaged in ‘preaching.’ In a meeting held at the Interior Ministry to review issuance of visas to Chinese nationals and registration of international nongovernmental organisations (INGOs), Nisar was told the couple was part of a group of Chinese citizens who obtained business visas from the Pakistani Embassy in Beijing. However, instead of carrying out any business activity, they were engaged in evangelical activities in Quetta, under the garb of learning Urdu language at the ARK Info Tech Institute owned by a South Korean national, Juan Won Seo.

On June 14, 2017, however, South Korea rejected Pakistan’s contention that the slain Chinese nationals were preaching Christianity under the guise of studying Urdu at a school run by a South Korean. An unnamed South Korean official asserted that there was no evidence to show the couple was involved in proselytizing under Seo’s guidance.

Meanwhile, China’s official media Global Times has criticized South Korean Christian groups for converting young Chinese and sending them to proselytise in Muslim countries. The kidnapping was a rare crime against Chinese nationals in Pakistan, but has alarmed the growing Chinese community in the country. A Global Times editorial argued, “while the atrocity” by the Islamic State in killing the two Chinese is appalling, it cannot drive a wedge between China and Pakistan, nor will CPEC construction be disrupted.

Behind the whole episode of Daesh’s abduction and killing of Chinese nationals, there is a clear intention of hurting Chinese interests. This is just the latest instance of Daesh targeting China, which is home to more than 20 million Muslims, including Uyghurs, in the Xinjiang province. In 2014, Daesh leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi explicitly equated China with the US, Israel and India as an ‘oppressor of Muslims’. That this was not mere rhetoric was demonstrated by the group’s subsequent execution of a Chinese citizen, Fan Jinghui, in Iraq on November 20, 2015. In February this year, ISIS released a slickly produced propaganda video detailing for the first time “scenes from the life of immigrants from East Turkistan [Xinjiang] in the land of the Caliphate” in which an Uyghur terrorist promised to “shed blood like rivers” to avenge Beijing’s alleged oppression in Xinjiang.

Arif Rafiq, fellow at the Centre for Global Policy, a Washington think tank, observed, on January 9, 2017, that “Balochistan provides IS with an opportunity to not only strike at Pakistani interests, but also those of China and Iran… Anti-state jihadis in Pakistan have previously sought to target Chinese citizens in Pakistan, knowing that this would strain relations between Beijing and Islamabad. Jihadis in Balochistan who’ve made the switch from al-Qaeda to IS are on a similar mission.”

Apart from Daesh’s abduction and killing of the Chinese couple, there has always been a lingering threat to Chinese engineers and workers associated with CPEC projects, as these have been rejected by Baloch nationalists who considers CPEC a ‘strategic design’ by Pakistan and China to loot Balochistan’s resources and eliminate the indigenous culture and identity. Dubbing China as a ‘great threat’ to the Baloch people, UNHRC Balochistan representative Mehran Marri argued, on August 13, 2016, that “China really-really is spreading its tentacles in Balochistan very rapidly, and therefore, we are appealing to the international community. The Gwadar project is for the Chinese military. This would be detrimental to international powers, to the people’s interest, where 60 percent of world’s oil flows. So, the world has to really take rapid action in curbing China’s influence in Balochistan in particular and in Pakistan in general.”

Pakistan currently hosts a sizable Chinese population and the numbers are slated to grow as the project progresses. Concern about the demographic transformation of Balochistan was reiterated in a report by the Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FPCCI) on December 28, 2016, which noted that, at the current rate of influx of Chinese nationals into Balochistan and after completion of the CPEC, the native population of the area would be outnumbered by 2048.

Pakistan earlier beefed up security around Chinese citizens streaming into the country on the back of Beijing’s OBOR infrastructure build-up across the nation. On February 20, 2017, the Government announced the creation of a special contingent of 15,000 personnel from the Maritime Security Force (MSF) and Special Security Division (SSD) to protect 34 CPEC related projects, including Gwadar and other coastal projects, and to ensure the safety of locals and foreigners working on CPEC projects. Senator Mushahid Hussain Sayeed, Chairman of the Parliamentary Committee on CPEC, after a committee meeting in Parliament House on February 20, 2017, disclosed, “The SSD is a force that will provide security to 34 CPEC related projects, while the MSF will safeguard the Gwadar port and other coastal areas of the country”.

Despite these security arrangements, militants succeeded in killing 10 labourers on May 13, 2017 and three labourers on May 18, 2017, at CPEC related projects in the Gwadar District of Balochistan. Since the start of CPEC projects in Balochistan in 2014, at least 57 workers (all Pakistani nationals) connected with these projects, have been killed. With global terrorist formations such as Daesh and al Qaeda entering the fray, and a range of domestic Islamist terrorist formations, prominently including LeJ-A and Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, as well as Baloch nationalist formations, all opposing the Pakistani state in general, and Chinese projects in the country in particular, this pattern of violence can only increase.

If China Does Build a Naval Base in Pakistan, What Are the Risks for Islamabad?

By Umair Jamal

The United States Department of Defense recently released a report concerning China’s military power. According to the report, China may be considering a large naval base in Pakistan as its potential second overseas military installation, after Djibouti.

Conventionally, Pakistan has maintained cordial relations with China for several decades and is now set to attract major investments from the latter as part of Beijing’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative. While Pakistan may not be overtly averse to the idea of a Chinese military base in Pakistan for different economic and security reasons, the country has had similar experiences in the past. Those experiences showed Pakistan the negative aspects of being a client state and had several unintended negative consequences.

During the late-1950s, the United States set up a military base in Pakistan as part of Washington’s security pact with Islamabad to contain the former Soviet Union. In the late 1970s and most part of the 1980s, Pakistan allowed the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) presence in the country to contain Moscow’s military intervention in Afghanistan and beyond. Following the 9/11 attacks, the regime of President Pervez Musharraf permitted the United States to set up military bases in Pakistan to conduct operations inside Afghanistan. The presence of American intelligence agencies in Pakistan was facilitated in different ways too: not only were CIA military installations were put in place in Pakistan, but there were also periods of close collaboration between the intelligence agencies of the two countries.

While the strategic nature of the intelligence collaboration between both countries cannot be denied, the presence of U.S.’s military bases on Pakistan’s soil has brought major challenges. Historically, the U.S. has used Pakistan’s soil to launch attacks in Afghanistan, which to some extent, have also exacerbated tensions between Kabul and Islamabad. Reportedly, the U.S. at one point was engaged in carrying out drones strikes in Pakistan’s tribal areas from its bases in the country that caused resentment among the wider public not just against the US, but also against Pakistan’s own ruling elite.

For Pakistan, arguably, the deadliest fallout of this collaboration was the rise of right-wing extremist Islamist and insurgent groups in the country, which turned against the state largely due to Islamabad’s military collaboration with Washington. Moreover, the fallout in this regard has also been due to Pakistan’s inability to manage Washington’s “soft power” image in the country, which has resulted in right-wing Islamist groups terming Pakistan’s ruling elite as American puppets while also targeting the state’s interests through violent and non-violent means.

Similarly, should Beijing build a naval base in Pakistan, there are considerable risks for Islamabad. While a permanent naval base in Pakistan extends China’s military outreach to safeguard its maritime interests, it reduces Pakistan to the status of a client state with higher risks of unintended consequences and few gains. Beijing’s traditional reliance on so called “commercial diplomacy” to extend its influence beyond its borders is fast becoming obsolete, for the country has in the last few years, actively sought to build its military muscle to protect its economic and security interests abroad.

While Pakistan, for its part, would like to see a Chinese military presence protect its interests, such as thwarting India’s growing naval power and maritime reach, Beijing’s agenda is hardly driven by Islamabad’s expectations and interests. China’s primary motivation in this regard stems from its desire to expand its global military reach. In the coming years, it’s likely that Beijing will actively rely on its military power to pursue interests globally.

For instance, India and China may have a border dispute, but the conflict between them is nothing like what it is between New Delhi and Islamabad. The only major point of contention between Beijing and New Delhi deals with both countries’ intense economic competition to gain regional and global influence. It’s highly probable that in the coming years, India and China’s bilateral confrontation will become reduced because of growing economic interdependence between the two countries and their mutual desire to maintain stability in the region.

This situation leaves Pakistan in a conundrum. Over the years, if Washington continuously demanded Pakistan’s compliance to deal with various insurgent groups that operate with its alleged support, it doesn’t mean that China will not ask for similar actions from Islamabad in the near future. In fact, compared to Washington, Beijing’s partnership is likely to prove more demanding for Pakistan.

Arguably, Islamabad’s deepening economic and military dependence on China doesn’t compare to the country’s decades-long association with Washington. With China, it’s perceivable that Pakistan may gradually lose its leverage as far as its domestic and regional security priorities are concerned, for, unlike Washington, any objection to Beijing’s demands may choke the country economically given Islamabad’s growing dependence on the country. While it’s unlikely that China may push Pakistan into an economic isolation, for Islamabad this threat will always remain a glaring possibility.

Moreover, Beijing’s naval base will always present the threat that Pakistan had with the presence of U.S. military installations in the country. Previously, military bases awarded for offensive and non-offensive operations have hardly remained in Pakistan’s control or under strict oversight. In China’s case too, the prospect of a military base in Pakistan being used without the consent of Islamabad or beyond the host country’s jurisdiction and interests will remain a likely scenario.

Pakistan needs to reassess its long term security and economic objectives before inviting China’s permanent military presence to the country, which places the country’s sovereignty at stake.

Pakistan’s war on minorities continues

The Baloch Regiment of Pakistan Army doesn’t have ethnic Baloch and the Sindh Regiment is with no Sindhis; this is the way Pakistan treats its religious, ethnic and linguistic minorities. This was revealed by Zulfiqar Shah, a Sindhi human rights campaigner who has been forced out of his country for his activism, at a conference on the condition of minorities in the neighbouring country.

According to Shah, the presence of Sindhis and Baloch in the two regiments of Pakistan army named after the ethnic groups is less than 1 percent.

Shah’s Institute for Social Movements was forcibly closed by the government and he had to take refuge first in Nepal and now in India.

Speaking at the conference of human rights of minorities in Pakistan by the Asia-Eurasia Human rights forum on Friday in Delhi, Shah said ethnic and religious minorities were facing the worst persecution in Pakistan. He said in Sindh, which has a sizeable population of Hindus (35% at the time of partition), the government was unleashing systematic persecution of the community.

Islamabad was also trying to make massive demographic changes in both Balochistan and Sindh to make the ethnic Baloch and Sindhis a minority in their own land. For example, he said, in Sindh, the government had launched two ambitious township projects where outsiders – mainly Punjabis would be settled. Similarly, another city at Gwadar port in Balochistan will be filled with settlers from Punjab, making the Baloch a minority.

Shah was forced to flee from Pakistan and take shelter with the UNHCR in Nepal after his institute was closed down and he felt the threat to his life. Even during his stay in Nepal, he said, the ISI tried to poison him and then he fled to India. He has been living in Delhi for four years and campaigns for the rights of minorities in Pakistan.

He told the gathering that the discrimination against the non-Punjabi speaking people is sanctioned by the government. “There are no jobs for Sindhis and even their language is not recognised.” He gave figures to show how Pakistan’s Punjab province used the bulk of the Sui gas (cooking gas) which originates in Sindh, while the local are deprived of it.

Ahmadiyas, who have been declared heretic by the Pakistani government, are not allowed to practice their religion. They are even barred from decorating their homes on Eid-ul-Milad-ul-Nabi (Prophet Mohammad’s birthday). He said Christians were being persecuted under the blasphemy law, while Hindus were facing pressure for conversion to Islam.

Pakistan - Anger grows in Parachinar after three attacks in six months

Members of the Shia community in Parachinar protested Monday as the death toll from twin blasts four days earlier rose to 97, marking a grisly Eid for the town worst hit by militancy so far in 2017.

Officials confirmed that five more injured of Friday’s blasts died in hospital, which pushed the death toll to 97. At least 10 others are said to be in precarious condition.

Dozens of protesters offered their Eid prayers wearing black armbands in the market in Parachinar, where the bombs tore through crowds of shoppers on Friday, local officials said.

“The death toll from Friday’s blasts has reached 97,” local administration official Basir Khan Wazir told AFP. He said the local administration was trying to negotiate with the protesters.

http://shiapost.com/2017/06/27/anger-grows-in-parachinar-after-three-attacks-in-six-months/

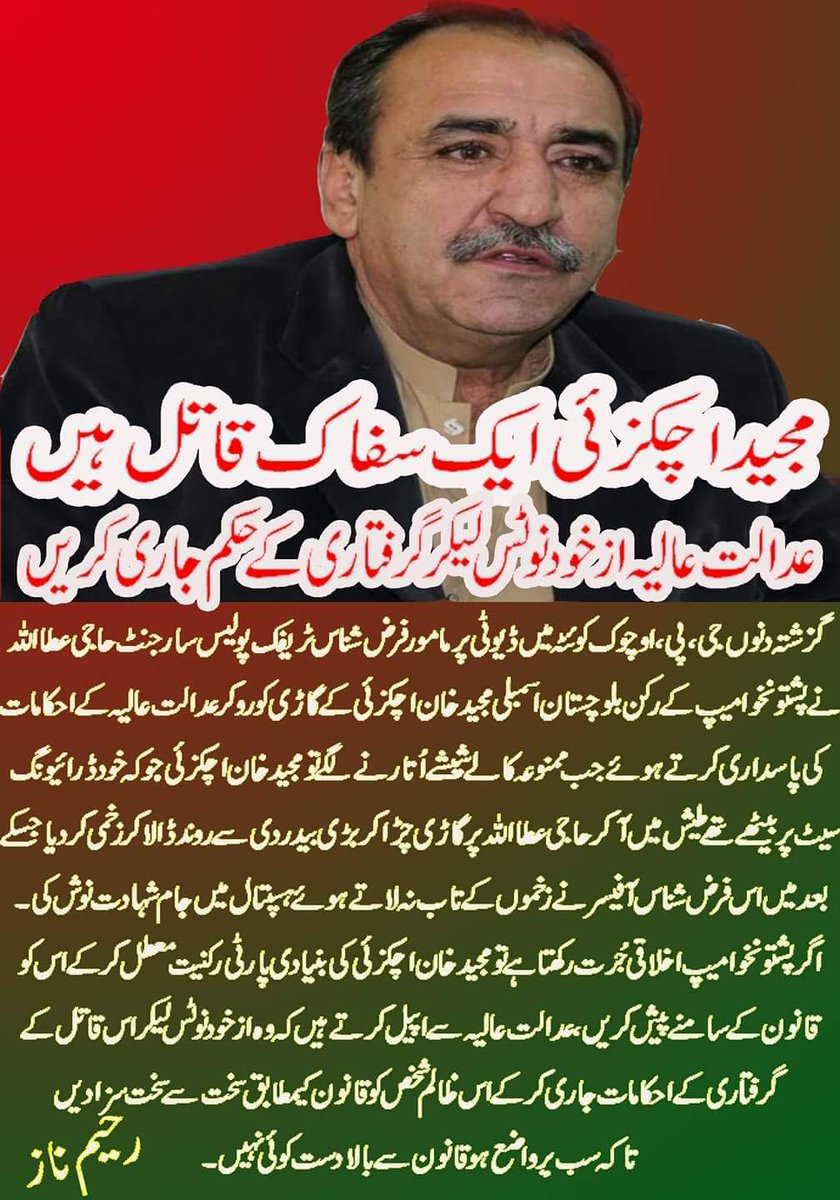

Social media activists seek justice for Traffic Constable allegedly killed by MPA Majeed Achakazi

Criminal silence of Pakistani media and political parties on brutal killing of police sargent #JusticeForPoliceSargent

Social Media activists have launched a campaign against Member of Provincial Assembly Abdul Majeed Achakazi, allegedly for killing a traffic constable by running his vehicle over him.

The traffic police Constable Haji Attahullah died after Pashtoonkhuwa Mili Awami Party (PK MAP) lawmaker Majeed Achakzai’s vehicle hit him at Shaheed Fayaz Sunbel Chowk on Tuesday night.

According to SSP Traffic Nazeer Kurd, Majeed Achakzai was driving the vehicle by himself.

Majeed Khan Achakzai is also heading the Public Accounts Committee as Chairman.

A twitter campaign has been launched usining the hashtag#JusticeForPoliceSargent

A Pakistani embarrassment And some Saudi confusion

This was not the first time Nawaz Sharif took himself seriously enough to think he could broker peace among the Arabs. He tried ahead of the first Gulf war – despite the imminent oil supply squeeze – and came back empty handed. Saddam refused to see him on the grounds that ‘he’s stationed thousands of troops for war against my country, and now he wants to come to my country to talk peace’, etc. And his meeting with Fahad barely made the news. He tried again after the Saudis executed – and beheaded and crucified, then dropped from a helicopter – Sheikh Nimr al Nimr, and was duly snubbed by Riyadh.

The latest episode is the most surprising. Once again he took the army chief, and his usual aides Sartaj Aziz and Ishaq Dar, to Riyadh to make peace between the Kingdom and Iran. Yet a good few days after his return the Saudi ambassador to Pakistan had to hold a press conference in Islamabad to clarify that Nawaz never really mentioned he was ‘mediating’. But since mediation is exactly what the prime minister’s office announced just before Nawaz took off, it seems that the Saudis just didn’t see the nine o’ clock news in Pakistan.

Still, they must have talked about something. And if Nawaz really thought he was mediating, he would have brought up better relations with Iran, etc, and the Saudis would have responded. But since the Saudis still do not believe he was mediating, what exactly did they talk about? It’s no secret that the Saudis have been increasingly annoyed with Pakistan since parliament’s refusal to play along in Yemen. It seems that the architect of the disastrous Yemen war, and now Saudi crown prince, might not be too happy with the arrangement with Pakistan as it stands. If Nawaz must talk to the Arabs, it should be about respecting Pakistan and its sovereignty.

Pakistan’s Christians at crossroads on divorce

(PIG) Zia is credited with the wholesale Islamisation of Pakistan. Yet not only did he make Muslims ‘better Muslims’ – it would appear he also transformed Pakistan’s Christians into ‘better Christians’. The dominant discourse in both the religious majority Muslim groups and religious minority groups became one of forsaking notions of human rights at the altar of particularist interpretations of their religions.

Yet all that is set to change for the latter. Or is it?

The Lahore High Court last week struck down an important Zia-era amendment to the Christian Divorce Act 1869. The question before the court had been whether General Zia-ul-Haq had constitutional legitimacy to delete Section 7 of the Act – pertaining to the particular grounds permitted for divorce – without first consulting the Christian community. Most of the community’s representatives responded on a basis that does not sit well with constitutional legitimacy.

Yet, notwithstanding the objections of obscurantist elements, the restoration of Section 7 must be welcomed, especially when it comes to the plight of women. For during its long absence, the only recourse available to Christians for divorce was Section 10, pertaining to adultery. For a wife, the burden was to prove additional cruelty or desertion in addition to adultery. This prompted many couples to convert to Islam to seek automatic dissolution of marriage. For a husband, the charge of adultery proved convenient since it incurred no liability of maintenance.

Chief Justice Mansoor Ali Shah observed that the Christian clergy and political leadership were united in their rejection of divorce – except in cases of adultery. He went on to note, however, that the Christian leadership had no opposition to Section 7 before the good general did away with it back in 1981.

Yet all that is set to change for the latter. Or is it?

The Lahore High Court last week struck down an important Zia-era amendment to the Christian Divorce Act 1869. The question before the court had been whether General Zia-ul-Haq had constitutional legitimacy to delete Section 7 of the Act – pertaining to the particular grounds permitted for divorce – without first consulting the Christian community. Most of the community’s representatives responded on a basis that does not sit well with constitutional legitimacy.

Yet, notwithstanding the objections of obscurantist elements, the restoration of Section 7 must be welcomed, especially when it comes to the plight of women. For during its long absence, the only recourse available to Christians for divorce was Section 10, pertaining to adultery. For a wife, the burden was to prove additional cruelty or desertion in addition to adultery. This prompted many couples to convert to Islam to seek automatic dissolution of marriage. For a husband, the charge of adultery proved convenient since it incurred no liability of maintenance.

Chief Justice Mansoor Ali Shah observed that the Christian clergy and political leadership were united in their rejection of divorce – except in cases of adultery. He went on to note, however, that the Christian leadership had no opposition to Section 7 before the good general did away with it back in 1981.

Yet one worrying development is the apparent conflict with religion. The Christian clergy stated before the court: “no one can change any verse or order of the Holy Bible”. Federal Minister for Human Rights Kamran Michael and Punjab Human Rights and Minority Affairs Minister Khalil Tahir Sandhu both voiced their support, with the latter reportedly telling the court that “divine laws could not be changed in the name of fundamental rights.” Such views are particularly worrying, given how close they are to the rhetoric promoted around Islam in the Zia era and its aftermath. Clearly the “Zia-isation” of the Christian community has proceeded abreast of that of the majority Muslim population of Pakistan.

All of which seemingly places Pakistan’s Christian community at the crossroads. Now is the time to decide whether it seeks validation of Zia’s blatant move to interfere in personal laws – or whether it stands for the constitutional and international human rights guarantees enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on Elimination and Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). These international standards require equal treatment of men and women before the law – and that, of course, includes fair and just mechanisms for marriage dissolution.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)