M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Wednesday, August 16, 2017

Pakistan court seeks to amend blasphemy law

By Saba Aziz

Legal experts discuss court ruling recommending a review of the controversial decree to prevent false accusations.

Blasphemy and accusations of the crime have led to the deaths of dozens of people in Pakistan since 1990.

Rights groups have repeatedly criticised and called for the reform or repeal of the country's controversial blasphemy laws, which date back to the British empire.

The Islamabad High Court asked parliament on Friday to make changes to the current decree to prevent people from being falsely accused of the crime, which is punishable by death if the Prophet Muhammad is insulted.

Other punishments include a fine or prison term, depending on the specific offence.

In a lengthy 116-page order, Justice Shaukat Aziz Siddiqui suggested that parliament amend the law to require the same punishment of the death penalty for those who falsely allege blasphemy as for those who commit the crime.

"Currently, there is a very minor punishment for falsely accusing someone of blasphemy," the judgement said.

Under the existing law, the false accuser faces punishments ranging from two years in prison to life imprisonment. Mehdi Hasan, chairman of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, welcomed the Islamabad court's move seeking amendment for the law.

"This law is being misused by people to take revenge against their opponents, and it is very easy to charge anyone for blasphemy," he told Al Jazeera from Lahore.

Exploitation of law

Friday's ruling noted that some critics are demanding the law be abolished but Siddiqui argued that it's better to stop the law's exploitation rather than get rid of it.

A majority vote in the provincial assemblies is required for the law to be amended. Backing of that vote by the federal government would likely be needed for the Senate to move.

Decrees in Pakistan are derived from the British common law, but the constitution holds that no laws shall be passed that are against the teachings of Islam.

WATCH UpFront: Tahir ul Qadri: 'No rule of law' in Pakistan After previous unsuccessful attempts to amend the blasphemy laws, legal experts offered little optimism over the new recommendation.

"Blasphemy is a very difficult topic, and any small change will be opposed by the right when they feel like it's being watered down and by the left when they feel it's being made stronger," Angbeen Mirza, a lawyer based in Lahore, told Al Jazeera.

In late January, Pakistan's Senate officially took up the issue of the law's potential misuse for the first time in 24 years.

Analysts say previous attempts at reviewing the law have been thwarted by the pressure of religious parties who, along with most in society, see it as "equivalent to religion" in the country.

"The religious right is on the offensive in Pakistan and because of the apologetic attitude of all governments they do not take a stand," Hasan said.

Legal experts say instead of repealing the law, legislation to curb false accusations and hate speech is required to deter the decree's exploitation for personal gains.

"An accusation of blasphemy hardly ever results in legal process," Mirza said.

"When someone makes an accusation, the neighbours do the rest."

She added: "The justice system is slow and provides no protection, leaving the accused at the mercy of the people".

Aarafat Mazhar, an independent researcher of Pakistan's blasphemy laws, said there is a tendency in the country to resort to public accusations rather than formally registering a case.

"Labelling a specific person or a community as being a blasphemer or just being anti-Islamic in general can be a death sentence and is a cause for disruption in public order," he said.

"Constitutionally speaking, such speech is not protected, and there is a definite need for legislation."

Culture of intolerance

Tahir Mahmood Ashrafi, a religious cleric and chairman of the Pakistan Ulema Council, said while there can be no room for change in the existing law, a review to prevent its misuse should take place.

However, beyond legal parameters,it is thought that a culture of intolerance towards free speech and religion is at the root of problem.

"Other countries have survived without blasphemy provisions," Mirza said. "All they regulate is hate speech. By creating offences where there should probably be none, Pakistan is creating hatred."

"Other countries have survived without blasphemy provisions," Mirza said. "All they regulate is hate speech. By creating offences where there should probably be none, Pakistan is creating hatred."

In a December 2016 report, rights group Amnesty International condemned Pakistan's blasphemy laws for "violating human rights" and called for their abolition.

While not a single convict has ever been executed for blasphemy in Pakistan, currently about 40 people are on death row or serving life sentences for the crime, according to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.

ncreasingly, however, right-wing vigilantes and mobs have taken the law into their own hands, killing at least 69 people over alleged blasphemy since 1990, according to an Al Jazeera tally.

In April, a university student, Mashal Khan, was killed and two others wounded during a violent mob attack after being accused of committing blasphemy in the northern city of Mardan.

In two prominent cases in 2011, Salman Taseer, governor of Punjab, and Shahbaz Bhatti, minorities minister, were both assassinated within two months of each other for asking for the law to be reformed.

Taseer's killer and bodyguard, Mumtaz Qadri, was hanged in February 2016.

Ashrafi blamed the judiciary's failure to hand down timely judgements for the rise in public tensions.

"When the punishments are not given, or the judgements are not passed on time, then people get an opportunity to take the law in their own hands," he said.

Academic circles in Pakistan advocate more research and urge authorities to learn from the example of other Muslim countries.

"The point is to make sure that our laws are aligned with the fundamental rights promised in the constitution," Mazhar said.

"Death or nothing is a rhetoric that creates a false binary and leads the conversation nowhere."

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/08/pakistan-court-seeks-amend-blasphemy-law-170814120428595.html

China Contributes To Doubts About Pakistani Crackdown On Militants – Analysis

China, at the behest of Pakistan, has for the second time this year prevented the United Nations from listing a prominent Pakistani militant as a globally designated terrorist. China’s protection of Masood Azhar, who is believed to have close ties to Pakistani intelligence and the military, comes days after another militant group, whose leader is under house arrest in Pakistan, announced the formation of a political party.

The two developments cast doubt on the sincerity of Pakistan’s crackdown on militants a day after a suicide bomber killed 15 people when he rammed a motorcycle into a military truck in Quetta, the capital of Balochistan. Balochistan, a troubled province in which the military has supported religious militants an anti-dote to nationalist insurgents, has suffered a series of devastating attacks in the last year.

Taken together, the developments are unlikely to help Pakistan as the Trump administration weighs a tougher approach towards the South Asian country as part of deliberations about how to proceed in Afghanistan where US troops are fighting the Pakistani-backed Taliban.

US National Security Adviser Gen H.R. McMaster warned a week before the Chinese veto and the announcement of the new party, Milli Muslim League (MML), by Jamaat ud-Dawa (JuD), a charity that is widely viewed as a front for Lashkar-e-Taibe (LeT), a group designated as terrorist by the UN, that President Donald Trump wanted Pakistan to change its ‘paradoxical’ policy of supporting the militants.

“The president has also made clear that we need to see a change in behaviour of those in the region, which includes those who are providing safe haven and support bases for the Taliban, Haqqani Network and others,” Mr McMaster said.

Mr. McMaster said that the US wanted “to really see a change in and a reduction of their support for these groups…. They have fought very hard against these groups, but they’ve done so really only selectively,” he added.

Pakistan’s military and intelligence have used militant groups to maintain influence in Afghanistan and to support protests as well as an insurgency in Indian-administered Kashmir. China’s repeated veto of a UN designation of Mr. Azhar, whose group, Jaish-e-Mohammed, has been proscribed by the international body as well as Pakistan, is not only bowing to Pakistani wishes but also a way of keeping India on its toes at a time of heightened Chinese-Indian tension.

Mr. Azhar, a fighter in the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan and an Islamic scholar who graduated from a Deobandi madrassah, Darul Uloom Islamia Binori Town in Karachi, the alma mater of numerous Pakistani militants, is believed to have been responsible for an attack last year on India’s Pathankot Air Force Station. The militants, dressed in Indian military uniforms fought a 14-hour battle against Indian security forces that only ended when the last attacker was killed.

Mr. Azhar, a portly bespectacled son of a Bahawalpur religious studies teacher and author of a four-volume treatise on jihad as well as books with titles like Forty Diseases of the Jews, was briefly detained after the attack and has since gone underground.

Freed from Indian prison in 1999 in exchange for the release of passengers of a hijacked Indian Airlines flight, Mr. Azhar is also believed to be responsible for an attack in 2001 on the Indian parliament in New Delhi that brought Pakistan and India to the brink of war. JeM despite being banned continues to publicly raise funds and recruit fighters in mosques.

JuD sources said the charity’s transition to a political party was in part designed to stop cadres from joining the Islamic State (IS). They said some 500 JuD activists had left the group to join more militant organizations, including IS. They said the defections often occurred after the Pakistani military launched operations against militants in areas like South Waziristan.

Pakistan listed LeT as a terrorist organization in 2002, but has only put JuD “under observation.” Pakistan’s media regulator in 2015 banned all coverage of the group’s humanitarian activities by the country’s news media.

JuD’s head, Muhammad Hafez Saeed, a UN and US-designated terrorist and one of the world’s most wanted men, has been under house arrest in Pakistan since early this year. Mr. Saeed is believed to be among others responsible for the 2008 attacks on 12 targets in Mumbai, including the Taj Mahal Hotel, a train station, a café and a Jewish centre. Some 164 people were killed and more than 300 wounded. The US government has a bounty of $10 million on Mr. Saeed who was once a LeT leader. He has since disassociated himself from the group and denied any link between JuD and LeT.

“What role (Saeed) will play in the Milli Muslim League or in Pakistan’s ongoing politics will be seen after Allah ensures his release. (Once he is released) we will meet him and ask him what role he would like to play. He is the leader of Pakistan,” MML leader Saifullah Khalid told a news conference. Mr. Khalid added that Mr. Saeed’s release was high on the MML’s agenda.

Mr. Saeed was not present at the conference, which was attended by Yahya Mujahid, a close aide of his, who is also subject to UN terrorism sanctions.

Treating men like Mr. Azhar and Mr. Saeed with kid gloves is unlikely to earn Pakistan any goodwill in Mr. Trump’s Washington. China’s protection of Mr. Azhar, moreover, undermines its sincerity in claiming that it is cracking down on militancy despite its harsh policy in the restive province of Xinjiang. If anything, it could put Beijing in Mr. Trump’s crosshairs too.

Opinion: Pakistan - India: The anniversary of hatred

By Shamil Shams

India and Pakistan became independent from British rule in 1947, yet they are still belligerent neighbors locked in territorial disputes and deep mistrust. The scar of partition remains unhealed, says DW's Shamil Shams.

It was a violent partition. Around 1 million people died as a result of it, and millions more were uprooted and displaced. The Indian subcontinent, which was home to people of different faiths, was divided and maimed. A nation was forced out of it on the basis of religion, of otherness and mistrust. It was named Pakistan. The birth pangs, the mayhem, the physical and emotional suffering never left the former British colony. As India and Pakistan celebrate the 70th anniversary of their independence from British rule, the idea of division and separation remains as stark as it was on the midnight of August 14-15, 1947.

The first few months after the partition set the tone for the future of Indian-Pakistani relations. The two states became embroiled in a territorial conflict over the Kashmir region, with Pakistan's founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah's aides sending a batch of tribal warriors to "liberate" Kashmir from the rule of a Hindu maharaja. As a result, India dispatched its troops to the area, occupying most of the land, while Pakistan took control of the rest. Both countries have fought three wars over Kashmir, and the conflict continues to be the biggest impediment to cordial bilateral ties. With Pakistan's support of Islamic separatists, the once secular and indigenous dispute has been transformed into a battle fought along communal lines.

As early as 1948, the two nations sought to outdo each other's influence in Afghanistan, a region that British rulers could never win over. Pakistan feared that a pro-India government in Afghanistan could pose a threat to its existence, with many ethnic Pashtuns also unhappy with Jinnah's authority and seeking unity with Afghanistan - also a Pashtun-majority area. That was the beginning of the Afghan conflict, which culminated in the former Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan. As New Delhi was closer to Russians, Pakistan offered its full support to the United States, plunging the region into a deadly civil war that continues to this day.

The initial foreign-policy decisions taken by both countries have had a deep impact on their domestic policies, too. The mistrust of each other has seeped into their official propaganda, their history books, their security apparatus and, more significantly, their psyche.

Another partition

When Bengalis living in the then eastern part of Pakistan (now Bangladesh) started demanding their rights and autonomy, the first reaction of the authorities in then West Pakistan was to label them as "Indian agents." The Muslim-majority East Pakistan's close proximity to India, its historical links to Indian Bengal and cultural affinity with Bengali Hindus were major reasons behind this suspicion. The unnatural line of partition that was carved out of bloodshed in the western parts of British India was missing in the east. Ironically, the All-India Muslim League, which demanded a separate country for Indian Muslims, was founded in Bengal. But Jinnah's idea of winning greater political and legal rights for the minority groups in India was severely betrayed by his successors in Pakistan. Pakistani rulers refused to accept the Bengalis' demands and used force against them, which resulted in an independence movement in East Pakistan and the foundation of Bangladesh in 1971.

It was the second partition in a span of 24 years - another violent partition that claimed the lives of millions of Bengalis. Thousands of Bengali women were raped, intellectuals tortured and houses burnt. Islamabad has never apologized to Bangladesh over the 1971 massacre and officially "justifies" the conflict by accusing India of conspiring to disintegrate Pakistan.

The second partition was also a result of a mutual fear of each other. The "enemy" discourse that was set into motion by Jinnah and leaders of the Indian National Congress in 1947 perpetuated itself in 1971, consolidating hatred.

Amnesia about partition

Most problems that India and Pakistan face today are rooted in the 1947 partition. Any scholarly study in post-colonial theory would point to similar issues in other parts of the world as well, be it the Middle East, Latin America or Africa. In India, there is still talk about partition and its effects, but there is an absolute silence over it in Pakistan, even though discussing partition would be an essential step toward solving the issue of political and economic governance in Pakistan.

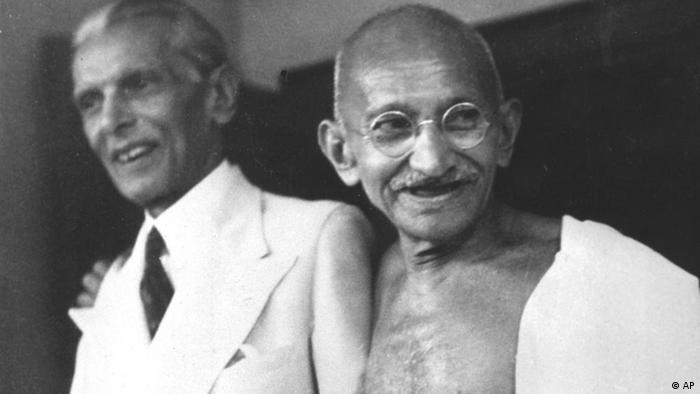

Jinnah (l.), seen here with Mahatma Gandhi, believed Hindus and Muslims could no longer coexist peacefully in one country

The "elite capture" of the state in 1947, with the British-backed land-owning class seizing the newly independent country's resources and its governance, remains intact, as well as the persecution of religious minorities that was a result of the so-called "two-nations theory" on which Pakistan was founded. We also need to revisit the Indian partition to understand why Islamist extremism has swept across Pakistan or why the state chose to use Islam as a foreign and security policy tool. Today, when Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is bent on reviving Hindutva, a Hindu supremacist ideology, we need to go back to the 1947 partition to trace its roots.

India and Pakistan celebrate the 70th anniversary of partition with nationalistic fervor, but there is nothing much to celebrate for the people of the two countries. While both nations boast of having nuclear weapons, advanced militaries and defense systems, the majority of Indians and Pakistanis do not have access to basic facilities. Yet the warmongering on both sides continues, witha falsified history about India's partition is being fed to the subcontinent's denizens - stories of fake glories and false supremacies.

It is not the 70th anniversary of independence; it is the 70th anniversary of animosity. The partition cannot be undone, but the wall of hatred can be brought down. Let's bring down this wall!

How have India and Pakistan fared economically since partition?

When India and Pakistan became independent 70 years ago, they were at the same level of development, with both equally poor and wretched. But the economic gap between them is growing.

Persistent underdevelopment has afflicted the Indian subcontinent since the region was unshackled from the chains of British colonial domination seven decades ago. South Asia's growth and development have been underwhelming compared to those of places like Northeast and Southeast Asia.

The region's independence from British rule was marked by its partitioning along religious lines, giving birth to a Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan as two independent countries. At the time of their independence in 1947, they both found themselves at a similar level of socio-economic development. The two newly formed nations were desperately poor and desiccated, home to hundreds of millions of destitute, illiterate and malnourished people.

India started its independent journey with an advantage by inheriting public institutions set up by the British during their rule. It also had a bigger share of the urban population, industry and transportation infrastructure. Pakistan, on the other hand, had the upper hand in agriculture, as the nation's territory composed of a huge tract of the alluvial, irrigated land of Punjab.

The two countries dreamt of rapid economic advancement, in the hope that it would uplift millions of their impoverished citizens.

Similar paths

There was significant convergence in their economic policies in the 1950s and 60s. Inspired by the Soviet Union and skeptical of capitalism, both sides designed centrally planned, state-led economies. The focus was on import substitution and self-sufficiency. Unsurprisingly, it was accompanied by their governments executing protectionist and interventionist policies, holding down growth and sustaining widespread poverty.

Inequality was as much a problem then as it is now. In the 1970s, redistribution of wealth came to dominate political discourse in both countries. While India's then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi captured public imagination with her "gharibi hatao" (eliminate poverty) call, her Pakistani counterpart Zulfikar Ali Bhutto popularized the slogan "Roti, Kapda aur Makan" (food, clothing and shelter).

Gandhi's radical approach to economic management was epitomized by her drive to nationalize a number of industries, including banking, insurance, coal and steel. Across the border, Bhutto, too, was committed to a strong state control over the economy. He also nationalized financial institutions as well as a number of other sectors.

The stated intention behind the nationalization drives in both nations was to reduce inequality and share economic prosperity more widely. But the policies slowed down growth, drove away foreign investment and discouraged entrepreneurship. Economists claim they actually increased inequality rather than decreasing it.

In Pakistan's case, political and security risks also grew in the 1980s. The rise of sectarian conflict and the emergence of religious political parties were compounded by the proliferation of extremist ideologies and violence emanating from Pakistan's involvement in the Afghan War. These factors, too, had a negative effect on the Pakistani economy and people's well-being.

Opening up

The growth-crippling policies ultimately caused myriad and complex dysfunctions in both economies, hurt development efforts and sparked severe crises by the late 1980s and early 1990s. The large deficits and balance-of-payments difficulties forced the two nations to knock on the door of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help. Pakistan went to the IMF in 1988 and India in 1991.

Both nations had to implement some radical free-market reforms, liberalizing and opening up their economies. But while India approached the IMF only once for help in 1991, Pakistan has sought assistance from the fund 12 times since 1988.

It reflects the diverging paths the two nations' economies have taken since then.

"Since 1990, as India has moved ahead with economic liberalization and major reforms, Pakistan has become mired in episodes of political turmoil and economic crises," said Rajiv Biswas, Asia-Pacific Chief Economist at IHS Markit, a global information and analytics firm. "India's economy has outperformed Pakistan during this time, and the country has achieved a more balanced and sustained macroeconomic performance."

This striking progress by India has drawn the attention of the global investor community and magnified the economic gap with its neighbor. Still, experts point out that despite India's relatively better performance, per capita GDP levels are still broadly at the same level. "India's per capita GDP has reached an estimated $1,930 in 2017, while Pakistan's per capita GDP is estimated at $1,560," Biswas told DW.

Energy-sector crises have contributed significantly to Pakistan's economic problems, with large power-sector debts and inadequate electricity-generating capacity resulting in severe power shortages. They have acted as a key bottleneck for industrial development, prompting the government in Islamabad to make power infrastructure a key focus.

Undertaking reforms

Both India and Pakistan continue to remain notorious for red tape and cumbersome barriers for private sector investment flows, with India still ranked 130 out of 190 countries in the 2017 World Bank Ease of Doing Business Index, while Pakistan is slightly worse with a ranking of 144.

That's why they have been focusing their efforts on pushing through critical reforms aimed at easing infrastructure bottlenecks, accelerating growth and spreading prosperity, with mixed results.

India's economy is expected to show sustained rapid expansion of around 7.5 percent per year over the next five years, boosted by the government's initiatives to streamline the nation's clumsy tax regime, accelerate infrastructure investment and bolster manufacturing. The Pakistani economy, meanwhile, is estimated to grow at a pace of around 5 percent per year over the next five years.

Islamabad pins its growth hopes on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a joint multibillion-dollar project, which is expected to channel tens of billions of dollars in Chinese investment into Pakistan. Experts reckon the initiative could give a fillip to expansion over the next five years.

Less integration

Political and border tensions between Pakistan and India over the past seven decades, and the ensuing deep-seated mutual mistrust and hatred, have spilled over into the economic arena, hindering any meaningful commercial partnership between them. The bitterness and suspicion between the two sides have also contributed to their committing enormous financial resources toward defense and national security, thus resulting in far lower resources available for other areas such as education and health in a region where millions still live on less than 2 dollars a day.

Furthermore, they have pushed South Asia behind others in terms of economic integration. The region is plagued by high trade barriers, underdeveloped transport infrastructure and regulatory hurdles, among a slew of other problems. And it remains much less integrated into global manufacturing supply chains.

For the situation to improve, analysts say, both countries need to find a more peaceful coexistence built on bilateral trade and investment flows.

"The EU example, whereby Germany's relations with other European nations have been built on peace and stability with steadily improving economic and political ties in the aftermath of two devastating world wars, should serve as a role model for future India-Pakistan relations," said economist Biswas.

Pakistan - No country for the poor

The dream of Pakistan was not to just create a country for Muslims but to create a country where the poorest sections of society would be taken out of the centuries of poverty they had gone through. The 1945 Muslim League manifesto included promises of land rights for the landless and rights for the working class. Much of these promises led to the popular support that the party was able to gain in the last election before independence. The dreams of poor peasants and poor workers were shattered quite quickly. Bureaucratic rule was followed swiftly by military rule in the new country. Party-based elections were not held for more than two decades. The political stifling produced a context which allowed an undercurrent of pro-working class, pro-poor politics to topple the Ayub dictatorship. When elections were held in the 1970, left-wing political parties were elected in all four provinces of West Pakistan. In the 1970s, Pakistan experimented with state-led socialism, which despite its failures gave hope to the poor that ‘roti, kapra and makaan’ were their basic rights. The rights of food, clothing and housing had become entrenched in the public imagination of the poor – but the dream was trampled over by another military dictatorship.

The dream of Pakistan was not to just create a country for Muslims but to create a country where the poorest sections of society would be taken out of the centuries of poverty they had gone through. The 1945 Muslim League manifesto included promises of land rights for the landless and rights for the working class. Much of these promises led to the popular support that the party was able to gain in the last election before independence. The dreams of poor peasants and poor workers were shattered quite quickly. Bureaucratic rule was followed swiftly by military rule in the new country. Party-based elections were not held for more than two decades. The political stifling produced a context which allowed an undercurrent of pro-working class, pro-poor politics to topple the Ayub dictatorship. When elections were held in the 1970, left-wing political parties were elected in all four provinces of West Pakistan. In the 1970s, Pakistan experimented with state-led socialism, which despite its failures gave hope to the poor that ‘roti, kapra and makaan’ were their basic rights. The rights of food, clothing and housing had become entrenched in the public imagination of the poor – but the dream was trampled over by another military dictatorship.

Politics in Pakistan changed fundamentally after the 1980s. While we focus on the Islamisation project of the decade, what is ignored is what the decade did to working class politics in the country. Workers’ unions and farmers’ organisations were declared illegal and many were broken through violence. When democracy returned to Pakistan, those that came into power belonged to the economic elite. Elections became more and more about who could spend the most money in the electoral process. No poor person can contest elections – even going down to the local bodies level. If we scour our legislative assemblies, they are made up of the who’s who of local and national elites. Can the poor hope for their deliverance from a legislature and executive made up of the richest people in the country? There is something fundamentally wrong with the social contract that has been given to the poor. Seventy years later, over 30 percent of Pakistan’s population still lives in abject poverty. Public-sector hospitals and public-sector schools are getting poorer every year. This is a failure of the process of representation. Pakistan’s failure to develop economically is claimed to be one of the fundamental reasons why people continue to live in abject poverty. But no one who witnesses the lavish lifestyles of the richest families in Pakistan can say that we have not seen economic development. Instead, it is a reminder that the question of the redistribution of wealth which was raised in 1945 and then again in the 1970s must be asked again.

Pakistan - Awam taqat ka sarchashma hain

By Wajid Shamsul Hasan

For most of our 70 years, the apex judiciary has been nothing more than a puppet on the string of the Praetorian establishment.

Pakistan has entered its 71st year of independent existence with great national fervour. The hallmark of the celebrations was the hoisting of the largest Pakistani flag by Army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa on the Pakistani side of the Wagah border. While the President, Prime Minister and leaders of all political parties too talked of their renewed commitment to make Pakistan role model as per the vision of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, one gets the impression that none was clear in one’s mind as to what actually vision of MAJ was.

Only redeeming feature of the day was often reference was made to MAJ’s landmark speech of August 11, 1947 in which he laid bare blueprint for his Pakistan. It was to be a secular, liberal democratic state with equal rights to all its citizens irrespective of their religion, gender or class. And categorically Pakistan was not to be a theocratic state-religion would have nothing to do with the business of the state.

Since interpretation of Pakistan’s ideological moorings differ from person to person, there is also confusion in the minds of academics. However, it is good to note that times have changed. Even former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif who has been a true political heir of Pakistan’s worst anti-secular and religiously rabid dictator General Ziaul Haq — seems to have turned a new leaf. On 70th Independence Day at Allama Iqbal’s mazar ousted Prime Minister declared that it was time for the nation to build Pakistan that was envisioned by MAJ. The need of the hour is to resolve once and for all the fundamental issue: who is the sole arbiter of power in Pakistan? If Jinnah were alive today, the Pakistani masses would have been the sovereign and sole arbiter of power, or as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto put it — awam taqat ka sarchashma hain Besides, he wants a new social contract, redesigning of democracy, drastic amendments in the constitution and has started talking of ushering in a revolution — whatever he means by it. One thing is for sure, he wants to get rid of Article 62 and 63 that he had refused to amend when PPPP wanted to when it introduced 18th Amendment in 2010. Now MNS is so desperate that he wants it done retrospectively. His opponent Imran Khan is opposed to any amendment. His diehard supporter Maulana Fazulur Rehman too is opposed to it.

With confusion worst confounded, one also heard a sweeping but very significant comment on the eve of August 14. One would not like to name the person since despite hearing him in TV news coverage of the Wagah flag hoisting function, one found it conspicuously missing in the print media. However, what was said about the current situation in the country was definitely music to ears. As I heard it the remark was as follows: “Today all the institutions in Pakistan are working within the framework of the constitution and rule of law. And Inshallah, Pakistan will continue to move forward on the path to progress. If any force came in its way then Pakistan army will confront it.”

This statement does not seem to be meaningless. It is a fall out of earlier events including former Prime Minister’s confrontation directly with the judiciary and indirectly with the establishment. Although MNS was responsible twice for the ouster of Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and once of PPPP Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani by conspiring against them with extra-constitutional forces, now he is lamenting that no prime minister was allowed to complete his or her tenure. Seventy years down the road, where do our institutions stand today is a question that begs an answer. Except for the army or the establishment nothing seems to be functioning well. Most of our 70 years apex judiciary has been puppet on the chain of the Praetorian establishment. It acted as an executioner to judicially murder Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto on the orders of General Ziaul Haq.

Earlier and later too, our superior judges happily danced on the tunes played by the establishment to justify dismissals of prime ministers on the basis of Doctrine of Necessity or on charges of corruption based on newspapers report. Only once in 1993 Supreme Court did not approve of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s dismissal on charges of reports of corruption against him.

Most significant was the case of Prime Minister Mohammad Khan Junejo. His dismissal was challenged in the Supreme Court. When it was to order for his restoration, the then Army Chief General Aslam Beg sent Acting Chairman Senate Waseem Sajjad to the Chief Justice to tell him if Junejo was restored, martial law would be imposed. One could write more including General Hameed Gul’s creation of IJI in 1988 elections, ISI’s secret funding of political opponents of Benazir Bhutto including Nawaz Sharif and of course massive rigging to stop her landslide victory at least twice.

In democracy besides the role of apex court, performance of Election Commission matters most. Unfortunately like judiciary, conduct of successive Election Commissions too have been most questionable. Except for 1971 elections, results of successive elections to this date have been marred by allegations of rigging.

Even last elections results were allegedly managed by Returning Officers. In neighbouring India elections are held regularly, never has any one ever challenged the sanctity of the Indian Election Commission or the results. Similarly, no decision of the Indian Supreme Court has ever been questioned as have been influenced by the executive or the military. In Pakistan doubts a galore about every major judicial decision or election result.

Situation being that, Chairman Senate Senator Raza Rabbani has suggested convening of tripartite conference comprising of three major institutions — Parliament, Prime Minister and the Establishment. It needs to be debated if this tripartite moot would be able cut the Gordian knot or not. Irrespective, the need of the hour is to resolve for all times the fundamental issue — who is the sole arbiter of power in Pakistan. If MAJ were alive today, in his Pakistan masses would have been the sovereign — sole arbiter of power or as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto called — awam taqat ka sarchashma hain.

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari discussed political situation with former President Zardari

Chairman Pakistan Peoples Party Bilawal Bhutto Zardari arrived in Lahore from Karachi and held meeting with former President Asif Ali Zardari discussing prevailing political situation in the country.

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari apprised former President of highly successful public gatherings in Chitral and Chiniot.

Vice President Pakistan Peoples Party Parliamentarians Mian Manzoor Watto, Senator Farhatullah Babar, Senator Qayyum Soomro, Senator Salim Mandviwala, Qamar Zaman Kaira, Nadeem Afzal Chan, Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar, Bashir Riaz, Mehreen Anwer Raja, Makhdoom Shahabuddin, and Faisal Mir also called on Asif Ali Zardari and discussed political situation in the country.

Former President instructed Party office bearers to chalk out strategy for bye-election in NA 120. He also asked party workers to campaign vigorously for party candidate in NA 120.

https://mediacellppp.wordpress.com/2017/08/16/bilawal-bhutto-zardari-discussed-political-situation-with-former-president-zardari/

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari apprised former President of highly successful public gatherings in Chitral and Chiniot.

Vice President Pakistan Peoples Party Parliamentarians Mian Manzoor Watto, Senator Farhatullah Babar, Senator Qayyum Soomro, Senator Salim Mandviwala, Qamar Zaman Kaira, Nadeem Afzal Chan, Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar, Bashir Riaz, Mehreen Anwer Raja, Makhdoom Shahabuddin, and Faisal Mir also called on Asif Ali Zardari and discussed political situation in the country.

Former President instructed Party office bearers to chalk out strategy for bye-election in NA 120. He also asked party workers to campaign vigorously for party candidate in NA 120.

https://mediacellppp.wordpress.com/2017/08/16/bilawal-bhutto-zardari-discussed-political-situation-with-former-president-zardari/

Pakistan - Don't want to be in contact with Nawaz, says Zardari

Pakistan Peoples Party supremo Asif Ali Zardari said on Wednesday that he has no interest in establishing contact with former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, reported Geo News.

Sources said the former president made the comments during a meeting of the party's core leadership at Bilawal House.

Zardari said the PPP also has no interest in becoming part of a 'Grand National Dialogue' proposed recently by Nawaz Sharif.

Sources quoted Zardari saying that the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz chief has a different attitude when he is in power and a completely different tone when he is not.

https://www.geo.tv/latest/153901-dont-want-to-be-in-contact-with-nawaz-says-zardari

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)