M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Sunday, November 11, 2018

Why Did The Pakistan Army Kill The ‘Father Of Taliban’? – OpEd

By Nauman Sadiq

On Friday evening, Maulana Sami-ul-Haq was found dead in his Rawalpindi residence. The assassination was as gruesome as the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. He was stabbed multiple times in chest, stomach and forehead.

Sami-ul-Haq was widely known as the “father of the Taliban” because he was a renowned religious cleric who used to administer a sprawling religious seminary, Darul Uloom Haqqania, in Akora Khattak in northwestern Pakistan. During the Soviet-Afghan War in the 1980s, the seminary was used for training and arming the Afghan so-called “Mujahideen” (freedom fighters), though it is now used exclusively for imparting religious education. Many of the well-known Taliban militant commanders received their education in his seminary.

In order to understand the motive of the assassination, we need to keep the backdrop in mind. On October 31, Pakistan’s Supreme Court acquitted a Christian woman, Aasiya Bibi, who was accused of blasphemy and had been languishing in prison since 2010. Pakistan’s religious political parties were holding street protests against her acquittal for the last three days and had paralyzed the whole country.

But as soon as the news of Sami-ul-Haq’s murder broke and the pictures of the bloodied corpse were released to the media, the religious parties reached an agreement with the government and called off the protests within few hours of the assassination.

Evidently, it was a shot across the bow by Pakistan’s security establishment to the religious right that brings to mind a scene from the epic movie Godfather, in which a horse’s head was put into a Hollywood director’s bed on Don Corleone’s orders that frightened the director out of his wits and he agreed to give a lead role in a movie to the Don’s protégé.

What further lends credence to the theory that Pakistan’s security establishment was behind the murder of Sami-ul-Haq is the fact that Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, a close associate of the Taliban’s founder Mullah Omar, was recently released [1] by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies and allowed to join his family in Afghanistan.Baradar was captured in a joint US-Pakistan intelligence operation in the port city of Karachi in 2010. His release was a longstanding demand of the Afghan government because he is regarded as a comparatively moderate Taliban leader who could play a role in the peace process between the Afghan government and the Taliban.Furthermore, Washington has been arm-twisting Islamabad through the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to do more to curtail the activities of the militants operating from its soil to destabilize the US-backed government in Afghanistan and to pressure the Taliban to initiate a peace process with the government. Under such circumstances, a religious cleric like Sami-ul-Haq, who was widely known as the “father of the Taliban,” becomes more of a liability than an asset.

It’s worth noting here that though far from being its diehard ideologue, Donald Trump has been affiliated with the infamous white supremacist ‘alt-right’ movement, which regards Islamic terrorism as an existential threat to America’s security. Trump’s tweets slamming Pakistan for playing a double game in Afghanistan and providing safe havens to the Afghan Taliban on its soil reveals his uncompromising and hawkish stance on terrorism.

Many political commentators in the Pakistani media misinterpreted Trump’s tweets as nothing more than a momentary tantrum of a fickle US president, who wants to pin the blame of Washington’s failures in Afghanistan on Pakistan. But along with tweets, the Trump administration also withheld a tranche of $255 million US assistance to Pakistan, which shows that it wasn’t just tweets but a carefully considered policy of the new US administration to persuade Pakistan to toe Washington’s line in Afghanistan.Moreover, it would be pertinent to mention here that in a momentous decision in July 2017, the then prime minister of Pakistan Nawaz Sharif was disqualified from holding public office by the country’s Supreme Court on the flimsy pretext of holding an ‘Iqama’ (a work permit) for a Dubai-based company.

Although it is generally assumed the revelations in the Panama Papers, that Nawaz Sharif and his family members own offshore companies, led to the disqualification of the former prime minister, another critically important factor that contributed to the downfall of Nawaz Sharif is often overlooked.

In October 2016, one of Pakistan’s leading English language newspapers, Dawn News, published an exclusive report [2] dubbed as the ‘Dawn Leaks’ in Pakistan’s press. In the report titled ‘Act against militants or face international isolation,’ citing an advisor to the prime minister, Tariq Fatemi, who was fired from his job for disclosing the internal deliberations of a high-level meeting to the media, the author of the report Cyril Almeida contended that in a huddle of Pakistan’s civilian and military leadership, the civilian government had told the military’s top brass to withdraw its support from the militant outfits operating in Pakistan, specifically from the Haqqani network, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad.

After losing tens of thousands of lives to terror attacks during the last decade, an across the board consensus has developed among Pakistan’s mainstream political forces that the policy of nurturing militants against regional adversaries has backfired on Pakistan and it risks facing international isolation due to belligerent policies of Pakistan’s security establishment. Not only Washington, but Pakistan’s ‘all-weather ally’ China, which plans to invest $62 billion in Pakistan via its China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) projects, has also made its reservations public regarding Pakistan’s continued support to the aforementioned jihadist groups.

Thus, excluding a handful of far-right Islamist political parties that are funded by the Gulf’s petro-dollars and historically garner less than 10% votes of Pakistan’s electorate, all the civilian political forces are in favor of turning a new leaf in Pakistan’s checkered political history by endorsing the decision of an indiscriminate crackdown on militant outfits operating in Pakistan. But Pakistan’s security establishment jealously guards its traditional domain, the security and foreign policy of Pakistan, and still maintains a distinction between the so-called ‘good and bad’ Taliban.Regarding Pakistan’s duplicitous stance on terrorism, it’s worth noting that there are three distinct categories of militants operating in Pakistan: the Afghanistan-focused Pashtun militants; the Kashmir-focused Punjabi militants; and foreign transnational terrorists, including the Arab militants of al-Qaeda, the Uzbek insurgents of Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and the Chinese Uighur jihadists of the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM). Compared to tens of thousands of native Pashtun and Punjabi militants, the foreign transnational terrorists number only in a few hundred and are hence inconsequential.

Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which is mainly comprised of Pashtun militants, carries out bombings against Pakistan’s state apparatus. The ethnic factor is critical here. Although the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) like to couch their rhetoric in religious terms, but it is the difference of ethnicity and language that enables them to recruit Pashtun tribesmen who are willing to carry out subversive activities against the Punjabi-dominated state apparatus, while the Kashmir-focused Punjabi militants have by and large remained loyal to their patrons in the security agencies of Pakistan.

Although Pakistan’s security establishment has been willing to conduct military operations against the Pakistani Taliban (TTP), which are regarded as a security threat to Pakistan’s state apparatus, as far as the Kashmir-focused Punjabi militants, including the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad, and the Afghanistan-focused Quetta Shura Taliban, including the Haqqani network, are concerned, they are still enjoying impunity because such militant groups are regarded as ‘strategic assets’ by Pakistan’s security agencies.Finally, after Trump’s outbursts against Pakistan, many willfully blind security and defense analysts suggested that Pakistan needed to intensify its diplomatic efforts to persuade the new US administration that Pakistan was sincere in its fight against terrorism. But diplomacy is not a pantomime in which one can persuade one’s interlocutors merely by hollow words without substantiating the words by tangible actions.

The double game played by Pakistan’s security agencies in Afghanistan and Kashmir to destabilize its regional adversaries is in plain sight for everybody to discern and feel indignant about. Therefore, Pakistan will have to withdraw its support from the Afghan Taliban and the Punjabi militant groups, if it is eager to maintain good working relations with the Trump administration and wants to avoid economic sanctions and international censure.

Pakistan’s government bows to Islamist right, victimizes anew woman in blasphemy case

By Sampath Perera

Bowing to the demands of the Islamist right, Pakistan’s three-month-old Tehrik-e-Insaaf (PTI) government has ordered the country’s Supreme Court to review its decision vacating the blasphemy conviction and death sentence imposed on Asia Bibi, an impoverished Catholic woman.

The government has also ordered that Bibi, who languished on death row for eight years, not be allowed to leave the country.

On Wednesday, Pakistani and international media claimed that Bibi had been allowed to go into exile. But Foreign Office spokesperson Dr. Mohammad Faisal has denounced these reports. “There is no truth in reports of her leaving the country—it is fake news,” Faisal told Dawn News Television. It subsequently emerged that the authorities had merely released Bibi from a Multan jail and flown her to Islamabad where she remains closely guarded for her own protection.

Pakistan’s highest court struck down Bibi’s 2010 blasphemy conviction and ordered her immediately freed in an October 31 ruling. While the Supreme Court framed its ruling within a defence of the legitimacy of Pakistan’s reactionary blasphemy laws, it said there was insufficient evidence against Bibi, including inconsistencies in the testimony of her accusers.

The Islamist right—which has long been cultivated by Pakistan’s ruling elite, especially the military-intelligence apparatus, as a bulwark against the working class and a weapon in its strategic rivalry with India—responded to the court’s verdict with calls for immediate mass protests.

From Wednesday, October 31, through Friday, November 2, Pakistan was rocked by violent protests led by the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP). In Karachi, Peshawar, Lahore and other cities, TLP supporters clashed with the police and set fire to vehicles and other property.

TLP co-founder Muhammad Fatal Badri told a Lahore rally that the three-judge bench of the Supreme Court led by the chief justice “deserve to be killed.” “Either their security, their driver, or their cook should kill them,” he declared. Badri also publicly urged Pakistani army officers to mutiny against the chief of the military, General Qamar Javed Bajwa.

Such threats by Islamists in Pakistan are not empty rhetoric. In 2011, Salman Taseer—Punjab’s provincial governor and an influential leader in the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), Pakistan’s then ruling party—was killed by his bodyguard after he advocated for Bibi’s release. Shahbaz Bhatti, the federal minister for Minorities Affairs and a Christian, was assassinated two months later, after declaring his opposition to Bibi’s incarceration and threatened execution. The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) claimed responsibility for the latter killing.

The TLP’s founding in 2015 and subsequent expansion was connected to the Pakistani state’s conviction and hanging of Taseer’s assassin. Sectarian attacks—especially those by suicide bombers linked to the TTP—have frequently targeted minorities in recent years, killing hundreds of men, women and children.

The rise of the TTP was itself a product of the Pakistani state’s decades-long promotion of Islamic fundamentalism and US-sponsored alliance with the Afghan mujahedin, on the one hand; and the brutal methods it has used—including carpet bombing and colonial-style collective punishments—in militarily suppressing support for the Taliban within Pakistan’s tribal areas since 2001.

In a televised speech on the evening of October 31, Prime Minister Imran Khan supported the Supreme Court’s ruling, admonished the protest leaders for their remarks against the judges and the military, and decried the violence and blocking of roads. He warned the protesters against pushing “the state to a point where it has no option but to take action.” However, two days later, as the Islamist rampage continued and the highway connecting Islamabad with Lahore remained blocked, the government pulled back from its harsh rhetoric and bowed to most of the TLP’s demands.

In addition to ordering the Supreme Court to review its decision, and placing Bibi under an arbitrary travel ban so as to prevent her from leaving the country, the government agreed to the immediate release of all TLP supporters arrested since the protests began.

In response, the TLP issued a token apology, mainly to appease the military.

A year ago this month, the TLP waged a campaign against the former Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) government’s attempts to amend the religious oath taken by election candidates, denouncing the government’s action as tantamount to blasphemy. This campaign, which brought the TLP to prominence, was tacitly supported by Pakistan’s military. The protests crippled Islamabad and involved a demand for the resignation of the minister for law and justice, Zahid Hamid, which the government carried out after the military announced it was “neutral” and would not disperse the protests.

The threat of the Supreme Court reversing its decision, turning Bibi, who is in her early 50s and a mother of five, back to the hangman’s noose, remains real. Her whole family also faces the threat of assassination or mob attack. Such attacks, resulting from blasphemy allegations, have caused the deaths of at least 65 people since 1990. Since 2010, Bibi’s husband has been living in hiding. Their two mentally and physically disabled daughters have had to live apart from him out of fear for their safety.

Bibi’s lawyer, Saiful Mulook, left the country last Saturday. “In the current scenario, it’s not possible for me to live in Pakistan,” he told the AFP. “I need to stay alive as I still have to fight the legal battle for Asia Bibi.”

The origins of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws lie in the British Raj, which promoted communalism as a key element in its colonial “divide-and-rule” strategy. They have been upheld and dramatically expanded under a succession of governments led by the military and all factions of the political elite, including the PPP, which once claimed to be an “Islamic socialist” party and today passes itself as the votary of Pakistani liberalism.

The blasphemy laws have served to intimidate critics of the government and religious obscurantism and to harass and terrorise minorities like the country’s Christians, who make up 2 percent of the population and are largely drawn from groups historically discriminated against as low-caste and “untouchable.” No one has yet been executed by the state after being convicted of blasphemy, but 1,472 people were charged under the laws between 1987 and 2016, according to the Lahore-based Centre for Social Justice.

The charges against Bibi, an impoverished farm labourer, emerged out of a 2009 dispute in a rural Punjab field. While harvesting falsa berries, she was asked to fetch water to share with the rest of the farmhands. After drinking from a cup next to the well, she was accosted by a Muslim neighbor of hers. The woman and the other farmhands refused to drink from the same well, claiming that being a Christian she had tainted it. As a result of the ensuing argument, Bibi was accused of insulting the Prophet Muhammad and arrested.

The backsliding of the Khan government is not a surprise. Khan has long courted the Islamist right, including by championing the blasphemy laws and supporting the disenfranchisement of the several-million-strong Ahmadi religious minority.

In September, Khan revoked the appointment of economist Atif Mian to his Economic Advisory Council when the TLP threatened protests against the inclusion of a member of the Ahmadi sect, which Islamic fundamentalists view as comprised of apostates. “The government wants to move forward with the religious leaders and all segments of society,” declared Information Minister Fawad Chaudhry in justifying Khan’s decision.

US imperialism has played a major role in the growth of the Islamic right in Pakistan. It staunchly supported the military regime led by General Zia ul-Haq (1977-1988), whose “Islamicisation” campaign spearheaded a political-ideological offensive against the working class and the left, and made Pakistan’s military-intelligence apparatus the linchpin of the CIA operation to organise and arm the mujahedin to wage war on Afghanistan’s Soviet-backed government .

It was under Zia that the punishment for blasphemy against the Prophet Muhammad was raised to “death, or imprisonment for life.”

While the government appeases the Islamist right and bows before its threats of violence, Pakistan’s military with the support of the PTI and complicity of the rest of the political establishment uses the threat of terrorist attacks and disorder to extend its power and reach.

This has included using the anti-terrorism laws against striking workers and to arrest leftists, and subjecting the press and social media to ever more severe censorship. Last week, the editors of the Dawn lamented that while the government had responded to the violent threats of the TLP leaders with talks, “Editors have been threatened; the distribution of newspapers disrupted; news channels taken off air or consigned to anonymous slots” for doing their “job and reporting events, facts and information.”

https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2018/11/09/pabl-n09.html

#Pakistan - SMOKERS’ CORNER: -POLITICS OF APPEASEMENT-

By Nadeem F. Paracha

In a recent statement, Shireen Mazari, the minister of human rights, equated her government’s ‘agreement’ with the agitating leaders of the Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) to British prime minister Neville Chamberlain’s “policy of appeasement” towards Nazi Germany.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the word ‘appease’ originated in the 14th century CE and means ‘to pacify’. However, the word’s political context is entirely a 20th-century construct.

According to Frank McDonough’s Chamberlain, Appeasement and The British Road to War, the word ‘appeasement’ (in its political context) was first used by Chamberlain’s critics to censure his ‘peace deal’ with German leader Adolf Hitler.State institutions may believe that a policy of appeasement avoids conflict, but in reality it offers nothing more than a brief respite.

In his 1983 essay for the Journal of Contemporary History, Prof Anthony Adamthwaite wrote that the British government’s soft stance towards the increasingly belligerent Nazi regime was explained as a way to avoid another war in Europe. This was the reason given by the British regime even when news about Nazi atrocities against opponents and its expansionist ambitions began to come out of Germany.

The perception that Germany had been handed a humiliating deal in 1919’s Treaty of Versailles was also used by the British government to draw support for Chamberlain’s policy. Adamthwaite wrote that Chamberlain’s government imposed strict media restrictions to curb newspapers from reporting criticism against Chamberlain’s policies, and even news about Nazi expansionism was largely repressed.

In 1938, on his return from Germany, Chamberlain triumphantly waved a piece of paper — ‘the Munich Agreement’ — claiming that this agreement will herald “peace in our time.” To critics, this was an act of surrender by an imperial power in front an aggressive fascist foe. On the other end, Hitler saw the agreement as Britain’s inability to halt Nazi Germany’s territorial ambitions. Hitler thus hastened his plans to invade various European nations and eventually triggered the Second World War in which millions of lives were lost.

Adamthwaite wrote that even though Chamberlain’s critics had warned that his “policy of appeasement” would only embolden Hitler, he dismissed them as being “pro-war.”

In his book, Strategy and Diplomacy, British historian, Paul Kennedy offered a more sympathetic view of Chamberlain’s policy. He wrote that there were limited choices at the time for Britain and one of them was appeasement. Britain’s economy had suffered during the global economic depression of the 1930s. Despite being an imperial power, the British state and government(s) were feeling vulnerable.

Yet, when in 1940 Winston Churchill was elected PM, he immediately undid Chamberlain’s policies. With some fiery rhetoric and carefully constructed alliances with the opposition Labour Party, the US and the Soviet Union, he managed to militarily hold back the Nazi war machine. Nazi Germany fell in 1945.

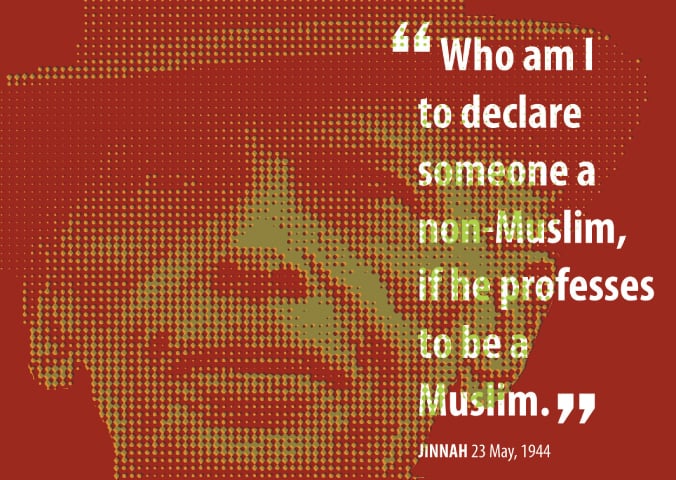

After the war, appeasement as a policy became anathema to Western states. It was to be avoided. Its opponents suggested that, whereas the idea of holding negotiations is agreeable, appeasement should be divorced from it because it immediately hands over the advantage to the other party. This sentiment was found not only among the Western post-war leadership. For example, Pakistan’s founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah was conscious of not giving too much leverage to India’s religious parties — even those who backed his call for a separate Muslim-majority state.To Jinnah, Islam — as it had meant to scholars such as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Syed Ameer Ali and Muhammad Iqbal — was something dynamic, democratic and ‘modern.’

According to Jamiluddin Ahmad’s book Speeches and Writings of Mr Jinnah, on May 23, 1944, when some supporters of Jinnah’s All-India Muslim League asked Jinnah to address the “Ahmadiyya question”, Mr Jinnah replied: “Who am I to declare someone a non-Muslim, if he professes to be a Muslim?”

In his book Jinnah Reinterpreted, Pakistan’s former ambassador Saad Khairi writes that, soon after Pakistan’s creation in 1947, during a party session chaired by Jinnah, a man, unhappy by the manner in which Jinnah had explained Islam, stood up and said: “But Jinnah Sahib, we have been promising people, ‘Pakistan ka matlab kya, la ilaha illallah ...!”

“Sit down!” roared Jinnah. “Neither I nor the working committee of the Muslim League have ever passed any such resolution. You might have done so to catch a few votes.”

The founders of Pakistan had their own idea of Islam that was rooted in the scholarly works of ‘Muslim Modernists’. There was no room in it to appease the idea of an Islamic state held by radical religionists. Even five years after Jinnah’s demise, the state of Pakistan unblinkingly crushed the first anti-Ahmadiyya movement, headed by religious groups, in 1953.

The Ayub Khan regime (1958-69), too, refused to exhibit any such leniency. Ayub refused to budge when religious parties protested against his government’s take-over of mosques, shrines and seminaries and the introduction of new family laws. The Islamic outfits decried these as being “un-Islamic.” Ayub held his ground.

The state, till then, was confident and clear about what the founders had stood for. But things in this context began to change after the 1971 East Pakistan debacle. As prime minister, Z.A. Bhutto was presiding over a country whose state and government institutions had been shaken by the 1971 episode, feeling vulnerable to disintegration. In 1974, while facing a 1953-like situation, his regime decided to agree to the demands of the agitators.Bhutto believed the state of Pakistan was not strong enough to withstand the consequences of the kind of operation undertaken in 1953. But even though his ‘capitulation’ in 1974 did manage to avoid what he feared, it turned out to be a short-term respite. Just three years later in 1977, his government was being attacked by the same forces he had appeased. The result? He tried to appease them again, but fell in a reactionary military coup.

The Gen Zia dictatorship (1977-88) fully adopted the agenda of the appeased. The appeased entered the parliament and, without much debate or hesitation, enacted laws that have created major political and judicial complications. So much so that post-Zia governments and state institutions believe they have no choice but to exercise appeasement to keep violence orchestrated by radical religious outfits in check.

But as we have seen on numerous occasions, moost notably with the accords signed with the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) radicals in Swat in 2011, these have only offered brief respite. What’s more, they have made governments and the state seem weak. The TTP clearly felt the same before organising its outrage in Peshawar which saw the slaughter of over 140 students.

Pakistan's lack of state writ - Vandal who?

As the nation recovers from Tehreek-e-Labbaik-Pakistan’s (TLP) latest protests, the costs of politicking in the name of religion are becoming clear. The Punjab government has prepared a report which outlines the private and public damages incurred due to the violent three day protests by TLP. The report estimates the cost of damages as Rs.260 million due to vandalism, destruction and rioting. This is in addition to the Rs143 million damages from the Faizabad sit-in of 2017. While the federal government gave into the demands of these extremists, it overlooked how hundreds of citizens across the country were directly harmed by vigilante mobs. The report captures the harrowing reality of Pakistan during those three days.

Another interesting revelation from the entire episode is the stark contrast between the depictions of the event on varying mediums for different groups. While mainstream media blacked out the protest entirely, and liberal critics were in an uproar regarding the violence, intimidation and lack of state writ — a completely different narrative was presented by the TLP. Blocked from mainstream media, digital platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Whatsapp facilitated news within conservative circles. What is illuminating is that these videos and messages show TLP workers cleaning up streets, distributing food, emphasising on the importance of a ‘peaceful protest’. Then there were those, present in the major sit-ins who had no access to any information due to jammed cellular networks.

Regardless of the conflicting narratives, the real issue here is the dwindling writ of the state. With questions pertaining to damage of public and private property and endless efforts to appease the Mullahs, the state is only repeating the unfortunate trends of the past.

While the government continues to issue and retract arrest warrants in the name of “public interest”, concerned Pakistanis hope that the judiciary will intervene. CJP Saqib Nisar has requested a full report regarding damages to ensure that affected citizens are duly compensated. Moreover, the suo motto case for the Faizabadsit-in, taking into account the role of TLP will be heard on November 16. It is time that the elected government and the permanent institutions of the state realised the gravity of this situation for the long term stability of the country.

#Pakistan - Explaining the #PTI’s poor performance

Whatever else might be said about the current PTI government, it cannot be denied that its first few months in office have been wildly entertaining (albeit in morbid, dark kind of way). When the government’s representatives are not fulminating against their predecessors, loudly vowing to bring about all manner of radical change, they are hastily recanting their previous statements, flailing wildly as their clear incompetence and lack of a plan hits the brick wall of reality. Who cannot remember the Prime Minister’s vows that rivers of milk and honey would flow within the first hundred days of his tenure as he transformed Pakistan into an Islamic welfare state? Alarm bells should have perhaps started ringing when considering how the Prime Minister’s plan was to model a twenty-first century nation-state on a seventh century Middle Eastern city, just as alarms should have been blaring when the auctioning of seven cows procured by the previous government was trumpeted as a vital part of the plan to plug Pakistan’s current account deficit. Pakistan is no stranger to the absurd antics of an arguably irredeemable political class distinguished only by its venality and incompetence, but the PTI government has thus far managed the dubious feat of making the past look good. When people start pining for the ‘good old days’ of the PML-N and even PPP governments, something is amiss in the status quo.

There are several possible explanations for the PTI’s lacklustre performance in government. The first, trotted out most frequently by those observing the government’s travails, points towards the relative inexperience of the party and its leaders. The argument here is that as a party enjoying its first actual taste of power, the PTI and its members will take some time to learn the ropes, and that its early missteps are nothing more than birth pangs that will likely be forgotten as the government makes itself more comfortable wielding the levers of power. There is some merit to this view except for a few inconvenient facts; the PTI was in power in Khyber Pukhtoonkhwa for several years prior to the 2018 elections, had participated vociferously in the national and provincial assemblies and most importantly of all, have years in which to prepare for power as it campaigned across the length and breadth of the country. Governing a country of 220 million people is not meant to be a walk in the park, nor is it a job that can simply be learnt on the go. To suggest that the PTI was not prepared to govern cannot be taken as anything other than a damning indictment of the party.

A second explanation, not too dissimilar to the first, acknowledges the missteps made by the PTI but attributes them to incompetence rather than inexperience. This line of reasoning suggests that despite having the best of intentions, the PTI simply lacks the capacity to formulate and implement policies that can help address the complex issues confronting Pakistan. How else, the argument goes, can one explain the government’s endorsement of the Chief Justice’s questionable plan to crowdfund the construction of the Diamer-Bhasha dam? Or the dogged belief that the Chinese government would bend over backwards to completely renegotiate the terms of CPEC? Or even the continued insistence, eventually prompting one of the Prime Minister’s infamous U-turns, that the country would never have to go to the IMF? The problem here is not that the government changes its mind, which is something that should be welcomed if changing circumstances prompt the decision to go in a new direction; what is troubling is that the PTI should have seen all of this coming and should have understood that the overblown rhetoric of its campaign would not necessarily translate into policy. That slogans could be mistaken for policy in the first place is what is truly troubling.

A more cynical view of the PTI might also suggest that the party’s problem is neither inexperience nor incompetence but, rather, a lack of concern about anything beyond its image and its optics. As has been discussed in this space before, the government’s continued reliance on empty stunts and gimmicks in the place of concrete action, and its unending use of campaign rhetoric to castigate and silence its political opponents, could be interpreted as a recognition of how, like other populist governments around the world, the PTI needs only to keep its base energised to remain in power. In a time of echo chambers on the internet and hyper-partisan media houses fuelling the spread of fake news and propaganda, it is easy to see how the PTI (and indeed any other party) might be tempted to rely on propaganda to reinforce its hold on power. As evidence from around the world currently shows, this tactic seems to be working, although it remains to be seen if it can continue to sustain the PTI’s momentum in the years to come.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it is necessary to recognise the structural conditions both underpinning and constraining the PTI government. As a populist party that came to power on the basis of bombastic rhetoric and the co-optation of traditional political elites the PTI, like Pakistan’s other mainstream parties, can hardly be considered to be ideological, let alone progressive. That the PTI has resorted to aping its predecessors, particularly when it comes to questions of economic policy, is hardly surprising in this context. Matters are made worse by the not entirely unreasonable suspicion that the party’s ties to the establishment, which were arguably instrumental in bringing it to power, further limit its ability to actually act on any radical impulses it might have. Further evidence for the party being constrained by its own contradictions comes from its response to the TLP, first promising to strike out against it before capitulating to it, releasing its activists who had been arrested for engaging in violence, and then blaming the opposition parties for the disturbances that accompanied the dharnas last week. Again, this is not conduct that should be surprising given how the PTI actively campaigned on religion and blasphemy to come to power.

Inexperience, incompetence, Insouciance, and inability, all are potential explanations for the PTI’s visible lack of performance in power. That the country may have to be subjected to almost five more years of this is a depressing thought.

#Pakistan - #AasiaBibi - Aasia and us

I.A. Rehman

No clear evidence is available to suggest any effort on part of the government to prevent the potential agitators from capturing strategic points on roads in cities and on highways.

Many questions have been thrown up by the way the government wasted its advantage in the matter of Aasia Bibi’s acquittal and negotiated a settlement that, on the face of it, looks like handing over an undeserved victory to Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP).

The first question is whether the government had prepared itself to meet the TLP agitation, that surely was not unexpected. A large number of people, including the TLP leaders, had come to know at least a day earlier when the Supreme Court was going to announce its verdict on Aasia Bibi’s appeal.

In Karachi, and possibly elsewhere too, posters attacking the convict’s acquittal had been printed before the judgment was announced and these were put on display immediately after the news of the decision was received. Obviously, the agitators had prepared themselves for both of the possible eventualities. Even a modestly efficient administration should have found out what plans the various parties were hatching.

The Christian community had reason to apprehend mob violence against them in the event of Aasia Bibi’s acquittal, and the provincial governments deserve credit for taking steps to protect them. These arrangements were however not tested as there are no reports of attacks on Christian settlements or offices of their organisations.

But no clear evidence is available to suggest any effort to prevent the potential agitators from capturing strategic points on roads in cities and on highways. This proved to be an extremely expensive lapse.

The government’s lack of a plan to deal with the situation is also confirmed by the confusion and indecisiveness seen in the way the TV coverage of the agitation was handled. In the beginning, no scenes of the agitators’ violent acts were allowed to be telecast, in the hope, probably, of preventing a snowballing effect, but the policy was changed later on and the coverage of acts of arson and vandalism did contribute to the erosion of public sympathy for the agitators.

The second question is as to why the government did not realise that several factors had made its position this time stronger than the protesters’. It was backed by a judgment of the apex court and that reduced the agitators’ cause to a totally unacceptable demand that everyone accused of blasphemy must be punished regardless of lack of evidence against him/her. Moreover, casting doubts on this verdict of the Supreme Court amounted to making its other judgments, from which the present political structure derives much strength, controversial.

The common citizens are justified in asking the government as to what happened to its will to establish its writ while the situation on the ground was in its favor.

The agitators lost the support of the business community and a large part of the country’s urban population by causing them material losses. This public mood probably persuaded some of the prominent religio-political outfits to put themselves at some distance from the agitators. They deplored acts of arson and destruction while remaining silent on the merits of the agitation. Above all, the agitators made the capital mistake of targetting not only the prime minister and the judiciary but also the army. This became evident on the very first day of the agitation because the prime minister gave special importance to the attack on the army.

The common citizens are justified in asking the government as to what happened to its will to establish its writ while the situation on the ground was in its favour.

Of the three possible ways of dealing with a situation like the one the government faced on October 31, the first one, that is, preventing a mob action, was missed as discussed above.

That left the authorities with two options: use of force to control the mob or to achieve the same result by peacefully demonstrating the futility of the agitation.

While the government has never been shy of using force to quell a protest by political activists, factory workers, teachers, lawyers, and even the visually impaired citizens, its ability to use force against a crowd that is appealing to the religious sentiments of the people is limited by several factors. The authority is afraid of escalation of conflict if the protesters are given dead bodies to whip up the people’s emotions. In addition to the fact that belief-related movements (Pakistan National Alliance in 1977 and Faizabad in 2017) have been more successful than secular political movements (anti-Ayub agitation in 1969 and Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in 1983 and 1986), the history of failure to suppress by force, movements launched under religious slogans is an inhibiting factor. A division within the establishment may make effective force unavailable to the government (PNA 1977, Faizaabad 2017).

However, the most decisive factor that undermines the government’s ability to use force against a mob raising, rightly or wrongly, religious slogans is that in most cases the government cannot repudiate the protesters’ core demand, which is roughly described as enforcement of a Sharia order. The government at the most claims to be better equipped than the agitators to achieve the shared objective. Thus, the government raises the threat from mob leaders to the level of a competition between them for realising a common ideal. Use of force against a crowd chanting religious slogans becomes an unwelcome hazard.

The government has also not been able to develop a strategy to overcome agitators through persuasion. Its negotiations with hardline agitators have ended more often than not in its capitulation. In the latest case too, the government rushed into negotiations with TLY apparently from a position of weakness. It might have improved its bargaining position by isolating the arsonists and destroyers of property from the TLY leadership and ordering a crackdown against the former before talking to the agitation organisers. Unfortunately, the government sued for relief in a state of panic and perhaps without a clearly thought out strategy.

The government’s case also suffers from treating any challenge from religious groups as a law and order problem. Eventually, the issue boils down to the government’s lack of a credible counter-narrative. The authorities did call out friendly religious scholars to deplore violence but their intervention was too little and a bit too late.

Unfortunately, the present government seems determined to appease the forces of religiosity to a greater extent than the previous governments. Any concession to these forces will inevitably lay the foundation of a new assault on the state’s political structure. The custodians of power in Pakistan are not strong enough to overturn the lesson of history that capitulation to unreasonableness never yields a fair dividend.

#Pakistan - Government only has ‘begging policy’: Bilawal

Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari has said the incumbent government only has the ‘begging’ policy.

Speaking to the media after the National Assembly session on Wednesday, he claimed Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government had no foreign and economic policy. He said only ten days were left in the 100 days agenda of the government but no promise had been fulfilled so far.

He criticised the government for increasing the prices of gas and electricity. He said the National Assembly does not debate on the national economy. He added that he was expecting a ‘tsunami of increased prices’ in days to come.

He claimed that the government was taking ‘U-turns’ on establishing the writ of the state.

Speaking to the media after the National Assembly session on Wednesday, he claimed Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government had no foreign and economic policy. He said only ten days were left in the 100 days agenda of the government but no promise had been fulfilled so far.

He criticised the government for increasing the prices of gas and electricity. He said the National Assembly does not debate on the national economy. He added that he was expecting a ‘tsunami of increased prices’ in days to come.

He claimed that the government was taking ‘U-turns’ on establishing the writ of the state.

https://tribune.com.pk/story/1842805/1-government-begging-policy-bilawal/

Speaking to the media after the National Assembly session on Wednesday, he claimed Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government had no foreign and economic policy. He said only ten days were left in the 100 days agenda of the government but no promise had been fulfilled so far.

He criticised the government for increasing the prices of gas and electricity. He said the National Assembly does not debate on the national economy. He added that he was expecting a ‘tsunami of increased prices’ in days to come.

He claimed that the government was taking ‘U-turns’ on establishing the writ of the state.

Speaking to the media after the National Assembly session on Wednesday, he claimed Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government had no foreign and economic policy. He said only ten days were left in the 100 days agenda of the government but no promise had been fulfilled so far.

He criticised the government for increasing the prices of gas and electricity. He said the National Assembly does not debate on the national economy. He added that he was expecting a ‘tsunami of increased prices’ in days to come.

He claimed that the government was taking ‘U-turns’ on establishing the writ of the state.Referring to the Pakistan and China currency policy, the PPP chairman said it was mentioned by Asif Ali Zardari. He added that it was acceptable as long as the government favoured the policy mentioned by the former president.

https://tribune.com.pk/story/1842805/1-government-begging-policy-bilawal/

#Pakistan - Government refuses to answer any question about economy, foreign policy: Bilawal Bhutto

Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) Chairman Bilawal Bhutto meted out severe criticism to the government, saying it has failed to provide answers to any questions regarding economy and foreign policy questions.Speaking with media, Bilawal Bhutto said that the government has no real foreign policy other than begging from other countries and International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Inflation in the incumbent’s government’s tenure is an all-time high, he claimed.The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) chairman Bilawal Bhutto further slammed the government for having contradictory policy on internal security.

He also responded to comments by some government ministers about imposing governor rule, saying the PPP will not submit to such threats.

Bilawal Bhutto, however, said that the PPP will support PTI if it forms a separate South Punjab province as promised by PTI pre-election or at least takes a concrete step towards it within the government’s first 100 days.

https://dailycapital.pk/news/top-stories/government-refuses-to-answer-any-question-about-economy-foreign-policy-bilawal-bhutto/

Senior Karachi journalist taken away by law enforcement agencies: journalist bodies

A senior journalist was allegedly taken away by law enforcement agencies from his home in Karachi on Saturday, according to media organisations.

Nasrullah Khan Chaudhry, a senior journalist associated with Urdu-language daily Nai Baat, was ‘detained’ by security personnel following a raid on his residence on Saturday morning. His whereabouts are not known, said a statement issued by the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) and Karachi Union of Journalists (KUJ-Dastoor).

An emergency meeting of PFUJ (Dastoor) was held at the Karachi Press Club (KPC) on Saturday under the chairmanship of its secretary general, Sohail Afzal Khan, and was attended by KPC office-bearers and senior journalists.

The participants expressed their concern over "illegal detention" of Chaudhry and termed it an attack on media freedoms.

The participants were of the view that the detention of the senior journalist was aimed at "sabotaging" the ongoing country-wide protest against the "forcible intrusion and harassment" of journalists by law enforcers at the KPC premises on Thursday night.

“High-handed tactics are being used to harass the journalists who were protesting against the intrusion by armed personnel and violation of sanctity of the KPC two days ago," the statement said.

The PFUJ has urged the Sindh governor, chief minister, Corps Commander Karachi, director general of Sindh Rangers and the inspector general of Sindh Police to take notice of the harassment of journalists and efforts to undermine freedom of the press. It has also demanded that Chaudhry be released immediately.

Journalists bodies have announced a protest against Chaudhry's 'detention' on Sunday outside the KPC.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)