M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Friday, October 8, 2021

Pakistan and The Protection of Different Religious Minority Groups – International Peace Day

Muzna Erum

In the 2018 Pakistani election, Imran Khan, the now 22 Prime Minister of Pakistan from the Tehreek-e-Insaf ( PTI) political party, vowed to protect ”the civil, social and religious rights of minorities; their places of worship, property and institutions as laid down in the Constitution.” This was an effort from the Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) political party goal, to create the “Naya” (new) Pakistan, providing justice to all, especially the different religious minority groups in Pakistan who live in constant fear from Blasphemy laws, violence, hate speech and discrimination. However, according to several reports in 2019 by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and watchdogs groups, not only is Pakistan a dangerous place for a great number of their Muslim citizens but increasingly dangerous for different religious minorities making them susceptible to many types of abuses and less support set in place such as legislation for protection. An article by the Diplomat noted that in 2019 although Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) political party promised a change, when it comes to truly protecting different religious minorities groups nothing much has actually changed.

Although 96.28 percent of the country consists of individuals who follow the Muslim faith, Pakistan is religiously, ethically, and linguistically diverse. Minority groups make 4% of the population, with Christians making up 1.59%, Hindus 1.60% and different sects of Muslim groups such as the Shia Muslim community making an estimated 20% percent of the Muslim population. Ismail Muslim and Ahmadiyya Muslims make 0.22 %, which has been contested as false as most Ahmadiyya Muslim followers do not publicly identify themselves due to the fear of persecution that the Ahmadiyya community continuously faces.

The Shia Muslims, according to the Pakistani Constitution, are not considered minorities, the Shia community, specifically the Hazar Shia community, has been experiencing the same or even more amount of violence as the other religious minority groups. As Saqib Nisar, the former Chief Justice of Pakistan, has put it the violence the Hazar community faces is “wiping out of an entire generation” of Shia Muslims.

In an email to the Organization of World peace (OWP) from the British Asian Christian Association (BACA) – an organization actively highlighting the ongoing abuse that Christian Pakistani believers face and working to help create legislation to protect Christians – listed out many cases of abuse, including young girls being kidnapped and forced into marriages by Muslims. In fact, Movement and Solidarity, a Muslim NGO, found that 700 Christian women and girls were kidnapped, raped and forced into Islamic marriages every year. But the most common type of abuse that Christians face living in Pakistan is blasphemy laws. Blasphemy laws are also an issue that a lot of different religious minority groups as well as the different Muslim sects face. Christians only make 1.59% of the population yet make up 15% of those accused of blasphemy.

Blasphemy laws have a long history in Pakistan all the way back, from form the British Colonial rule. According to section 295-C of the blasphemy penal code, the code charges anyone who makes derogatory terms against the prophet’s name or Quran. Most religious minority groups are continuously accused of blasphemy without any proof and face mob violence like Mashal Kahn, a student who was killed by a mob at Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan because a peer he knew had alleged he had committed blasphemy without any proof whatsoever. The mob ended up taking “justice” into their own hands, which is very common with many cases of an individual being accused of blasphemy.

In fact, it is noted that many blasphemy cases and individuals accused of blasphemy come from vendettas, personal disputes, and even full discrimination and intolerance. For example, with the case of Yaqub Maish, an 11-year-old girl with several mental conditions who lived in informal slums in a Muslim community as a Christian immigrant who was accused by a Muslim cleric living in the neighbourhood of shredding the Quran. This accusation was proven to be false as the Muslim cleric just wanted to get rid of Christian immigrants in the community. According to reports from the Centre for Social Justice, it was found that 1855 people have been charged with blasphemy in Pakistan, with a significant spike in 2021. The European Parliament, United Nations, and Amnesty International have called out for Pakistan to reform blasphemy laws; however, with the long history of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws and extremist Islamic groups, push back to see any reforms seems impossible.

According to Cornell’s Policy review on Blasphemy laws, Radicalization and Discrimination in Pakistan, the most realistic way to protect minorities from violence and discrimination is not through reforming Blasphemy laws but working towards de-radicalization. As BACA has pointed out “the only way to change the social malaise is to bring up a new generation of Pakistani citizens who have a broader understanding of other faiths, have been taught that the Quran itself does not endorse blasphemy laws and that Muhammed himself had often forgiven perpetrators of a blasphemy”. The popularity of the religious rights of Islamic extremists has prompted blasphemy laws to gain votes to not work towards any type of peace or co-existence with different religious minority groups and has created intolerance.

Muhammad Ali Ilahi on creating de-radicalization from Cornell’s Policy Review points out that to create peaceful coexistence and harmony, there needs to be reform at the most basic level of education – especially for the next generation. The Ministry of education can play a huge role in celebrating diversity and bridging differences in Pakistani history classes, creating less hate. In addition, religious and Muslim clerics with a lot of social power in Pakistan can promote progressive interpretations of Islam to counter the hardline extremist narratives. In fact, it has also been noted that Pakistan’s education plays a significant role in the discrimination that different religious minority groups face. An article by The Diplomat on the Pakistani public education system found that textbooks circulated around public schools to at least 41 million children contained derogatory references when it came to different religious minority groups fostering intolerance and creating radicalization. In an email with BACA on how peace and harmony can be created in Pakistan, BACA also noted the importance of creating a change in education systems stating “a new national curriculum should include the great contribution made by minorities to the development of Pakistan, in the fields of science, law, sports, business, our contribution to war efforts and much more”.International Day of Peace is celebrated on September 21 to cease all hostilities worldwide and promote peace and harmony. It is to ensure each individual of the world, regardless of race, ethnicity, age, gender, and religion lives in the world from fear of abuse and neglect. It is to make sure that there is the protection of people and all communities. It’s an opportunity to reflect on what can be done realistically for change to create peace, harmony, and co-existence. In Pakistan. the 2016 International Peace day was celebrated with 125 guests of Muslims, Christians, and Hindus to declare a day of peace and work towards harmony and co-existence.

https://theowp.org/reports/pakistan-and-the-protection-of-different-religious-minority-groups-international-peace-day/

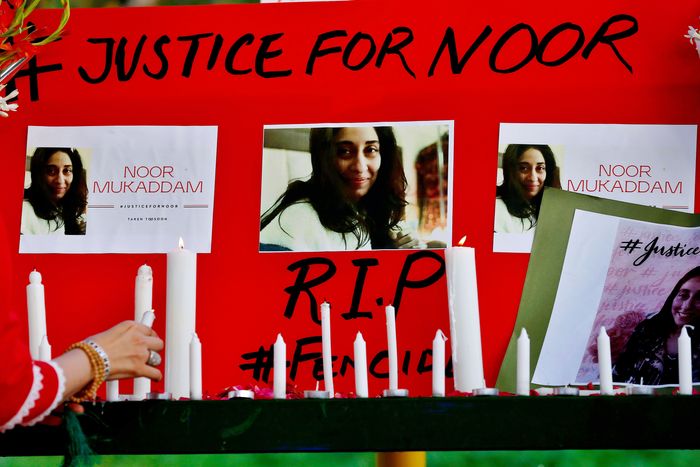

#JusticeForNoor - The Femicide Case That’s Captivated Pakistan

By Rafia Zakaria

Noor Mukadam was a charismatic and graceful woman, her father Shaukat Mukadam told the crowd. The late September vigil was being held for his 27-year-old daughter who was allegedly beheaded by Zahir Jaffer, an acquaintance of hers and scion of one of Pakistan’s richest families. “My daughter is gone,” Mukadam, a former diplomat and ambassador, told the group gathered before him, “but I want that all the daughters of Pakistan should remain safe.” As he broke into tears, his one demand for the upcoming trial, which was set to begin this week, was that there be justice for Noor.Noor’s murder took place among an especially horrific spate of crimes against women in Pakistan. It has captured the country’s attention not only because it’s especially gruesome but also because Pakistani women are utterly fed up with rich and powerful men committing crimes against them and getting away with it. Noor’s case has become a rallying point against the hypocrisy of a society where women are present in all sectors of the economy and public life but where there are few places for them to turn to when they face abuse at the hands of men. As Pakistan watches, feminists are wondering: Could this time finally be different?

The murder took place just over two months ago, on July 20. At around dusk, Zahir Jaffer, who had held Noor captive for the past two days, allegedly raped, tortured, and killed her. In the days following the crime, Zahir Jaffer’s parents, who phone records show were in contact with their son and household staff before and after the murder, were also arrested and placed in police custody, as were the household’s guards, cook, and gardener, all of whom were present at the time of the murder at the Jaffers’ sprawling home in the most exclusive enclave in Islamabad.

According to the police investigation and CCTV footage, Noor attempted to escape, but Zahir’s armed security guard did not let her leave. Later that evening, she jumped down from a balcony. This time, it was the gardener who locked the gate and refused to let her run. Zahir Jaffer emerged from the house and dragged her back inside by her hair. She was never seen alive again.

Zahir Jaffer’s multimillionaire parents then tried to orchestrate a cover-up, according to Islamabad police, calling a therapy center where Zahir had once been in treatment and asking them to send a team to their house, allegedly to dispose of Noor’s body. Had a neighbor not called the police, they may have been successful in doing so. Later that day, Shaukat Mukadam was asked to come to their home, where he identified the body and the severed head as Noor’s.

It would appear to be an open-and-shut case, but things are not simple in Pakistan. At the outset, there are laws that favor the powerful. These include ordinances that essentially permit any accused to be “pardoned” by the victim’s family. When the perpetrator is rich and the dead woman is poor, her family faces a lot of pressure to capitulate and grant the pardon. There are also unofficial ways to interfere: Police and even judges of the lower courts are poorly paid and often amenable to bribes. And since there is no jury trial in Pakistan, trial outcomes are decided by the judge alone. Powerful families can buy off witnesses or even pay armed thugs to intimidate or blackmail those refusing to do the bidding of the powerful. Pakistan’s confusing mess of parallel court systems also presents its own morass.

And despite the inordinate amount of violence Pakistani women face, they do not often see their perpetrators punished. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan recorded 363 honor killings of female victims in 2020, and according to a recent study from Pakistan’s Ministry of Human Rights, about 28 percent of women and girls between the ages of 15 and 49 have suffered violence during their lifetimes. Even when they make it in front of a judge, less than 3 percent of sexual-assault cases result in a conviction. A new bill that would criminalize domestic violence has spent months stalled in Parliament after some members from Islamist parties opposed it.

One reason Noor’s case has been able to evade the usual traps is because of the intense pressure from social media, where the hashtag #JusticeForNoor trends every time there are new developments. And while her case has certainly received more attention because of her upper-class background, it also aligns with growing anti-elitist sentiment in Pakistan; people who are not part of the multimillionaire elite have had it with the impunity with which men (and sometimes women as well) heap abuses on the less powerful. At his first press conference, Shaukat Mukadam alluded to the ruling Pakistan Justice Party, which vowed to hold the country’s corrupt elite class accountable: “The government belongs to the ‘justice’ party, and it should ensure that this justice is actually done.”

Feminists and anti-elitists are now speaking up in any way they can. YouTubers like Mahreen Sibtain and Maria Ali have been providing daily updates on the case, dedicating video segments to everything from how Zahir isn’t allowed to have a toothbrush in his cell to how his mother is spending her time in jail. Ali never once uses Zahir’s actual name, referring to him as “the beast” instead. Her anti-elitism is popular, particularly with middle-class women used to working hard for even the smallest privileges. It may not seem like a nascent feminist revolution, but this push for gender justice is supported by rapid urbanization and a critical mass of women entering the workforce. Increasingly unwilling to accept a dependent status, they are becoming more outspoken in their criticism of men.

But Noor’s killing has yet to be avenged. The trial was scheduled to begin on Wednesday, with the indictment of 12 people in connection with the murder. But before that could happen, lawyers representing Zahir’s parents introduced motions claiming they never received evidence from the prosecution, including the CCTV footage. Another motion alleged that Zahir has been unable to communicate with his lawyer. The start of the trial was delayed to October 14. This is not a good sign, but bringing the wealthy and powerful to task has never been easy anywhere. When it does begin, Pakistan’s women will be watching and waiting to see if the system will work, if there will be justice for Noor Mukadam and thus hope for them.

https://www.thecut.com/2021/10/noor-mukadam-murder-pakistan.html

The past few months have been harrowing for Pakistani women

Dr Nida Kirmani

There appears to have been a surge in violence against women, but in truth it is nothing new. It is just that we are more aware of it now and more women are fighting back.The last few months have been particularly harrowing for Pakistani women. From the horrific case of 27-year-old Noor Muqaddam, who was brutally tortured and beheaded in the nation’s capital on July 21, to that of Ayesha Ikram, a TikTok creator, who was harassed and groped on the country’s Independence Day by more than 400 men on the grounds of one of the country’s major national monuments, the Minar-e-Pakistan in Lahore – it feels as if violence against women has reached epidemic proportions. Many are even calling it a “femicide” to draw attention to the scale of the problem and its systemic nature. But gender-based violence in the country is not new. According to the 2017-2018 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey, 28 percent of women aged 15 to 49 had experienced intimate partner violence in their lifetimes. This is a slight decrease from 32 percent of the women reported to have experienced physical violence at the hands of their partners in the 2012-2013 survey. But given that domestic violence is an issue shrouded in secrecy and shame, both sets of figures are likely a gross under-estimation. One suspects that it feels like there is a surge in violence because cases are getting more attention. Mainstream media is more attuned to the issue, and it is also being highlighted and discussed on social media platforms. These conversations have created heightened awareness among young women in particular, who are becoming increasingly vocal about their rights. The vast majority of these women belong to the educated, urban middle and upper classes. This is just the latest in the long history of the struggle against gender-based violence in Pakistan. In the past, particular cases have drawn national as well international attention, leading to collective action by rights activists. One such case was that of 28-year-old Samia Sarwar, whose murder was arranged by her family in 1999. She had been seeking a divorce from her violent husband, a decision her family did not support because it would have “dishonoured” the family name. She was shot dead in the offices of Hina Jilani, a well-respected Supreme Court lawyer and human rights activist. Sarwar had been there for a pre-arranged meeting with her mother to receive the divorce papers.Her murder started a national conversation about honour killings. Women’s rights activists, including Jilani and her sister Asma Jahangir, also a renowned human rights lawyer and activist, highlighted it to advocate for an end to gender-based violence.But there were counter-protests from religious conservatives arguing that Sarwar’s feminist lawyers had no business interfering in a question of “family honour”. To this day, the perpetrators have not been brought to justice. Another well-documented case is that of Mukhtaran Mai, who was gang-raped in June 2002 by four men in Meerwala village in southern Punjab’s Muzaffargarh district. Mai was raped on the orders of a village council as “punishment” for her younger brother’s alleged illegitimate relationship with a woman from a rival tribe. And more recently, the murder of 26-year-old Qandeel Baloch by her younger brother in July 2016 for her “intolerable” behaviour, was a turning point for many younger feminists. Baloch was a social media star who was bold and open about her sexuality. Her murder set off a public debate around the question of women’s sexuality and victim-blaming. While cases such as these make headlines every few years, their frequency seems to have increased during the last five years. There are a few possible reasons for this. Social media Female education rates are gradually on the rise in Pakistan, with the rate of female secondary education rising from 28.6 percent in 2011 to 34.2 percent in 2021. There is now a new generation of young educated women who have the awareness and confidence to demand their rights. Additionally, as technology and social media have become more accessible, news of cases has started to spread more widely and at a much greater speed. As of this year, almost 27.5 percent of the country’s population has access to the internet, mostly through their mobile phones. While this is much less than the global average of 60.9 percent, it is still significant for a country of 223 million. Despite the fact that the country only has 2.1 million Twitter users, a relatively low percent, tweets are often featured by media outlets and are used to further discussions.The state has also identified social media as a possible threat to Pakistan’s national image. Fawad Chaudhry, the country’s information minister, recently alleged that Indian and Afghan accounts were “falsely” creating the impression that Pakistan is “unsafe for women”, which he argued is part of an international conspiracy to malign the country. With social media playing a key role in taking the conversation forward, women also face constant threats and harassment on these channels. Conservative commentators and groups use these to counter the claims of feminists by arguing that Pakistan is indeed one of the safest countries for women – a claim also repeated by the country’s Prime Minister Imran Khan. In June, rights activists condemned Khan’s comment that, “If a woman is wearing very few clothes, it will have an impact on the men, unless they are robots. It’s just common sense.” He later tried to backtrack on this, stating that only a rapist is responsible for their crime, but this too was couched problematically in a discussion about the need to lower “temptations” in society. Women’s March The last four years have also seen the emergence of Aurat March (Women’s March) in major cities across the country on International Women’s Day on March 8.They were first held in 2018 in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad, with hundreds attending. In 2019, they spread to Multan, Faisalabad, Larkana and Hyderabad, attracting thousands of participants.While most of those who attend are from the urban upper and middle classes, organisers have been working towards making the marches more inclusive; encouraging transgender women to participate and providing transport for working-class women to make it easier for them to attend. These demonstrations have highlighted gender-based injustices, such as domestic violence, sexual harassment, the undervaluing of women’s paid and unpaid labour, and lack of access to female healthcare. The issue of gender-based violence has consistently been front and centre. The growth in popularity of these marches can also be attributed, at least in part, to social media, with much of the publicity and conversations before and after the march taking place on various online platforms. Not part of the conversation These certainly are all hopeful signs of resistance, however, the vast majority of women in Pakistan are still not part of these conversations and the movement. There is still a long way to go in terms of diversification.For example, all of the high-profile cases mentioned earlier took place in the province of Punjab. Cases of violence against women from lower socioeconomic classes and from provinces other than Punjab, which has historically been the most economically and politically dominant province, rarely garner national attention. Pakistanis living in the country’s peripheries complain that women’s rights activists rarely take up their issues. Supporters of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM), which advocates for the rights of Pashtuns, the country’s second-largest ethnic group, highlighted the case of a woman in Khaisor, a village in the former tribal areas of Waziristan. She was allegedly harassed by security forces, with the details of the case surfacing on social media in 2019. This case received very little attention, both from feminist activists and the mainstream media, due to the gap between women in urban centres and those in rural and remote areas.Hence, while social media is helping to amplify the cases of violence against women, it has not been able to bridge the ethnic and class divides that have long existed in the country. In addition to this, the vast majority of women in Pakistan still do not use social media at all. There is a 65 percent gap in digital access between women and men in Pakistan, the highest such gender gap in the world, and the women who have access by and large belong to the upper and upper-middle class. Furthermore, as has historically been the case, progress on women’s rights is still frequently blocked by religious conservative groups, which often work in tandem with the state.Most recently, the Domestic Violence Bill – despite being passed by the National Assembly to ensure legal protection and relief for victims – was stalled after an adviser to the prime minister recommended that it be sent to the Council of Islamic Ideology for review. The victims of domestic violence continue to wait to find out what legal channels are available to them. The ‘woman card’ Despite the various hurdles that women’s rights activists face, from religious conservatives to the country’s ethnic and economic divisions, there are signs of a wider change in attitudes towards gender-based violence, and not just in the virtual realm. After the Minar-e-Pakistan incident, for example, hundreds of young women and men descended on the same spot where the Tik Tok star had been harassed a week earlier, in a bid to proclaim women’s right to occupy public spaces.On television talk shows, though largely dominated by male commentators, women journalists are increasingly vocal in their opposition to gender-based violence and are refusing to be silenced by male anchors and conservative commentators.Feminists are also creating alternative forums for discussion. For example, a group of women journalists recently started a channel on Youtube called Aurat Card (Woman Card), a tongue-in-cheek reference to the misogynistic claim that women use their gender to gain “unfair advantages”. The show presents critical views on a range of social and political issues.As a teacher, I have seen a change among university students during the last 10 years, where conversations about harassment are becoming increasingly frequent on campuses. However, with a female tertiary education rate of only 8.3 percent, even these conversations remain confined to a small section of the society, and that too in big urban centres. So, while violence against women appears to be at a peak and regressive forces are as vocal as ever, there are positive signs that women, particularly those who are young and educated, are becoming more aware and vocal in their resistance. Calling this a gender revolution may be premature, but a change is certainly taking place. The struggle for equal rights for women still has a long way to go, but the grip of conservative men is gradually being challenged and is loosening, and they have good reason to be scared. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/10/8/violence-against-women-in-pakistan-is-not-new-but-it-must-stop

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)