Saad Rasool

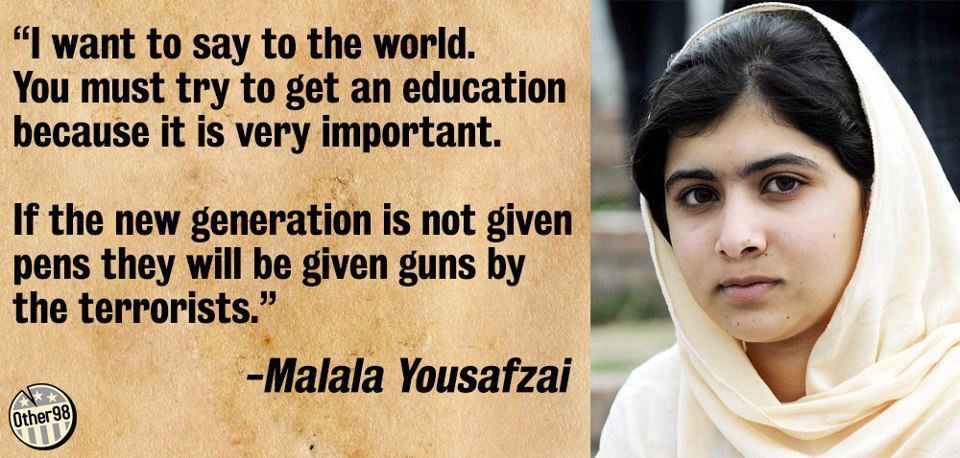

In September of 2014, DG ISPR revealed that ten militants had been arrested, as part of the ongoing military operation in North Waziristan, for having been directly involved in the assassination attempt on Malala Yousafzai, on October 9, 2012. These militants, all of whom belonged to the banned Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), admitted to carrying out the attack on the orders of Mullah Fazalullah, as part of a planned and deliberate exercise to assassinate Malala, a “Jewish agent”, for advocating education for young girls in Swat. The attack on Malala Yousafzai, in many ways, was a horrific precursor to the unfathomable barbarity committed in Peshawar, two years later.

At the time of the attack on Malala, in 2012, the entire country as well as the world-at-large, experienced an unprecedented surge of anger and disgust. It became apparent, almost instantaneously, that in the ongoing war against extremism, which in many ways is the defining battle of our time, the casualties would no longer restricted to uniformed officers or unassuming bystanders. The enemy had just spiked the temperature by identifying and attempting to kill a young girl (child), in school uniform, who believed in the purpose and promise of education. This perverse idea reached its boiling point in APS Peshawar, turning children into martyrs, and students into soldiers.

As the world focused its attention and prayers on the recovery of Malala, and her meteoric assent on the global platform, DG ISPR, unveiled the arrest of ten TTP militants in 2014. This news, at the time, received modest media attention, as the militants were presented before the Anti-Terrorism Court (ATC) in Mingora. And in the months to follow, the ongoing trial of these militants continued unnoticed, up until Friday of this week, when the country woke up to the startling revelation that eight out of ten militants had been freed by the ATC, and only two had been sent to serve a life sentence.

Reportedly, as confirmed by Regional Police Officer (RPO) Malakand Division and the District Police Officer (DPO) Mr. Saleem Marwat, the ATC sentenced two attackers, Israr-ur-Rehman and Izhar Ullah to life imprisonment, while freeing the other eight. This was despite the fact that (reportedly, some of) the accused had confessed to carrying out the assassination attempt on direct orders from the head of TTP.

It has been reported that the eight acquitted men were freed because of “a lack of evidence” against them. In fact, despite the public nature of the shooting, no one was willing to step forth and present ocular testimony against the accused, out of fear of repercussions from TTP militants and its sympathisers. The Court had to base its judgment on the scant evidence presented by the public prosecutor and the army officials. In the circumstances, per the established standards of our jurisprudence, which have been developed over the course of our common law history, the ATC freed eight out of the ten militants, swearing fidelity to the letter of the law as opposed to the spirit of justice.

The acquittals in Malala Yousafzai’s case, keeping aside the ongoing rumours of these being part of some secretive deal, once again bring to question the effectiveness of our laws, and the judicial system, to convict modern-day terrorists.

Borrowed from the centuries old dictums of English Common Law, and then interpreted and applied under the Pakistani law of the past seventy years, the criminal law jurisprudence of Pakistan, particularly as it relates to convictions for murder, require strict standards of admissibility of evidence, corroborating testimony, and ocular accounts. This model of conviction, evolved during a bygone era when crime, even murder, was unsophisticated in nature and rural in setting, is inadequate to grapple with the complexities of suicide attack or target killings. For the most part, modern-day terrorist attacks leave no witnesses; and in the rare cases where witnesses are available, there are no procedures in place to protect the identity or security of such testimony.

Beyond the obvious, as has now been established in repeated terrorist attacks, the planning and execution of the attacks carried out by outfits such as TTP, involve numerous individuals, disconnected with one another, and existing in disparate legal jurisdictions. The financing frequently takes place in the grey murk of international monetary transactions, and the planners (true culprits) mostly exist beyond the jurisdictional reach of the trial (even appellate) Courts. Faced with this complex myriad of an evolving terrorist organism, it would be naïve, if not foolish, to apply the conviction standards of Allah Ditta vs. the State.

The responsibility, in this regard, of convicting modern-day terrorists, rests (in equal part) with our investigating agencies as well as the superior Courts. Of course our investigating agencies must do better in collecting evidence for a prosecutable case. Of course we must do more to increase the capacity and expertise of our provincial police forces to collect untampered evidence that would result in a conviction in the court of law. Of course we must train our prosecutors better to present such evidence and effectively cross-examine witnesses.

But all of this would probably still not amount to a conviction unless we rethink the jurisprudential standards upon which terrorism cases are decided. And this responsibility resides with the honourable members of our superior judiciary.

The trial Court (a Court of first instance) is constitutionally bound to apply the precedents of the superior judiciary. The trial judge has no option but to award conviction or acquittal on precisely the contours set by the superior Courts. It is thus the responsibility of our superior Courts to evolve fresh standards for cases concerning terrorist activity.

It is time for us, as a constitutional democracy, to join step with the rest of the modern nations, most of which have already determined a different bar for admissibility of evidence in cross-border and international terrorist incidents. Standards of conviction that do not require eyewitness testimony, or corroborating witnesses, or nominating an individual in FIR, or an unbroken chain of financing records… what precisely these new standards might be, in fidelity to our constitutional spirit, is a question that can only be answered by the bench. What is evident, however, is that the existing standards no longer work.

Staying within the parameters of our Constitution, it is now the responsibility of our superior judicial officers to find a way towards regaining ground in the ongoing legal battled against hardened terrorists. Till such time that we find a solution to the terrorism problem in our civilian Courts, and are able to avenge Malala and APS Peshawar through it, the people of this country will have a legitimate (grief-stricken) reason to clamour for military Courts.

The judiciary, and the legal community, must rise to this occasion for the sake of its own legitimacy, as well as that of our Constitution.

No comments:

Post a Comment