Asad Hashim

Asad Hashim

More than 2.3 million have been forced from their homes across the conflict-ridden northwest since 2009.

Peace talks with the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) - the Pakistani Taliban - have broken down amid continuing violence, and with momentum gaining for the use of military force in the tribal regions, tens of thousands are fleeing in anticipation of a bloody confrontation.

As many as 40,000 people have fled the North Waziristan tribal area where the TTP and other armed anti-state groups are based, bound for the nearby areas of Bannu, Lakki Marwat, Karak and Kohat, locals told Al Jazeera.

A steady flow of residents are moving into adjoining districts, with one local journalist telling Al Jazeera he observed as many as 300 people leaving the tribal area, bound for Lakki Marwat, within just two hours last week.

It is almost impossible to get an exact figure of those who have fled in the latest wave of internal migration, which was sparked by a staccato series of military air raids that began in mid-January and have continued in response to TTP attacks on military and paramilitary forces, as the government has yet to establish any camps or registration systems for the new IDPs.

Security officials, speaking on condition of anonymity because they weren't authorised to go on the record, told Al Jazeera the military had killed between 60 and 100 people in the latest air strikes - mostly in the North Waziristan and Khyber tribal areas - carried out since February 16 when a faction of the TTP claimed responsibility for killing 23 Frontier Corps soldiers.

With the air raids and helicopter gunship attacks continuing, the government of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif also announced a shift away from a dialogue-driven approach, with the use of a full-scale military operation in the face of the TTP's refusal to declare a ceasefire increasingly seen as a possibility.

Such military operations have, in the past, created hundreds of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Pakistan. Since 2009, more than 2.3 million Pakistanis have been forced to flee their homes from across the country's conflict-ridden northwest, mainly from the Bajaur, Mohmand, South Waziristan and Khyber tribal areas, and the Swat Valley.

While many IDPs have since returned, there remain almost three-quarters of a million - 747,498 to be exact - displaced individuals who are either living in government-maintained camps, or on their own, according to the UNHCR.

History of Jalozai

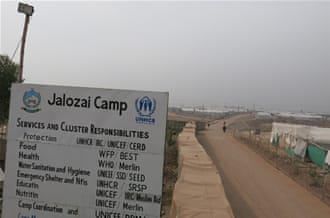

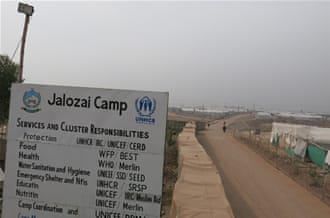

Almost 40,000 of those IDPs live in the Jalozai refugee camp, located about 40 kilometres southeast of Peshawar, the capital of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province.

Jalozai, a sprawling sea of tents, mud huts and unpaved paths, is spread out across about eight square kilometres of land. It is no stranger to providing refuge to those seeking respite from conflict. It was here that as many as 70,000 Afghan refugees fled after the Soviet Union invaded their country in 1979, and Jalozai grew over the years to become the largest refugee camp in Asia.

Back then, the camp was also a base for the "mujahideen", and, as recently as November 2012, long-buried surface-to-air Stinger missiles were still being found on its grounds. It is also home to a "martyrs graveyard" for those who fell fighting the Soviets, as well as Abdullah Azzam, a Palestinian cleric considered to be Osama Bin Laden's spiritual guide in waging global jihad. Azzam was killed by a car-bomb in 1989 in Peshawar, and his attackers, to this day, remain unknown.

The camp was officially closed to Afghan refugees in April 2008 - having seen its inhabitants swell to more than 300,000 at its peak following the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

By 2009, however, Pakistani IDPs displaced by military operations were already flooding into the recently closed camp. Today, it is home to 39,823 people - about 21,000, or 53 percent, of them children. Families of four to eight people often live in a single tent, or one-room mud hut, across the camp's eight sections.

"I came to the camp in 2009, from Bara [in Khyber agency]," says 45-year-old Khel Jan, who fled the violence there along with 20 family members. "The government told us to leave because of the military operation. We couldn't go back - I haven't even visited since then. If the government catches us when we are there, they accuse us of being Talibs, and if the Talibs catch us, they say we are government agents.

"I came here out of desperation. I had no choice."

Most of Jalozai's current inhabitants are, like Jan, from the nearby Khyber region, which adjoins Peshawar and has seen multiple large- and small-scale military engagements against groups allied with the TTP, including helicopter gunship operations in the past two weeks.

Rahim Khan, a daily wage labourer who fled Khyber agency in 2009, lives in a small hut with his family of 10, and echoes that sentiment of desperation.

"The situation was terrible there. There was no food for me or my family. There was government shelling, so we had to leave. We were desperate and even now we live in an IDP camp. We don't have a choice," the 48-year-old told Al Jazeera.

Longing for peace

With negotiations ongoing at the time of these conversations, camp residents expressed differing views on their expectations for results. Some felt the negotiations were "a drama", others said they wanted an outcome - but all agreed they desired a lasting peace so they could return home.

"If there is peace, regardless of whether it is the government or the Taliban in charge, we will go back," said Khan.

Jan, however, offered a different point of view, one echoed by others Al Jazeera spoke to.

"We fled our homes because of [the Taliban] - there is no point in sending us back to them. We will just have to flee somewhere else then."

That tension around whether or not there will be peace, says local official Raina Shah, is a central challenge for the Provincial Disaster Management Authority, which manages the camp.

"The biggest challenge is to convince these people that it is safe to return to their homes. Someone who leaves a war will be afraid to return - how do you convince them that it is safe? How do you remove the fear?"

In the meantime, those who are already displaced say they remain caught between a rock and a hard place, in an interstitial security space where they are treated with suspicion by both the Taliban and the Pakistani state.

"Right now, I have issues being both here and there," says 21-year-old Khanat Gul, who fled to Jalozai from Khyber agency when he was just 17. "Over here, the police harass me because my identity card says that I am from Khyber, and there the Taliban harass me. Refugees are more free in this country than we are."

Asad Hashim

History of Jalozai

Almost 40,000 of those IDPs live in the Jalozai refugee camp, located about 40 kilometres southeast of Peshawar, the capital of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province.

Jalozai, a sprawling sea of tents, mud huts and unpaved paths, is spread out across about eight square kilometres of land. It is no stranger to providing refuge to those seeking respite from conflict. It was here that as many as 70,000 Afghan refugees fled after the Soviet Union invaded their country in 1979, and Jalozai grew over the years to become the largest refugee camp in Asia.

Back then, the camp was also a base for the "mujahideen", and, as recently as November 2012, long-buried surface-to-air Stinger missiles were still being found on its grounds. It is also home to a "martyrs graveyard" for those who fell fighting the Soviets, as well as Abdullah Azzam, a Palestinian cleric considered to be Osama Bin Laden's spiritual guide in waging global jihad. Azzam was killed by a car-bomb in 1989 in Peshawar, and his attackers, to this day, remain unknown.

History of Jalozai

Almost 40,000 of those IDPs live in the Jalozai refugee camp, located about 40 kilometres southeast of Peshawar, the capital of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province.

Jalozai, a sprawling sea of tents, mud huts and unpaved paths, is spread out across about eight square kilometres of land. It is no stranger to providing refuge to those seeking respite from conflict. It was here that as many as 70,000 Afghan refugees fled after the Soviet Union invaded their country in 1979, and Jalozai grew over the years to become the largest refugee camp in Asia.

Back then, the camp was also a base for the "mujahideen", and, as recently as November 2012, long-buried surface-to-air Stinger missiles were still being found on its grounds. It is also home to a "martyrs graveyard" for those who fell fighting the Soviets, as well as Abdullah Azzam, a Palestinian cleric considered to be Osama Bin Laden's spiritual guide in waging global jihad. Azzam was killed by a car-bomb in 1989 in Peshawar, and his attackers, to this day, remain unknown.

No comments:

Post a Comment