I hope my film’s Netflix release makes Pakistanis see Abdus Salam beyond his Ahmadi faith.

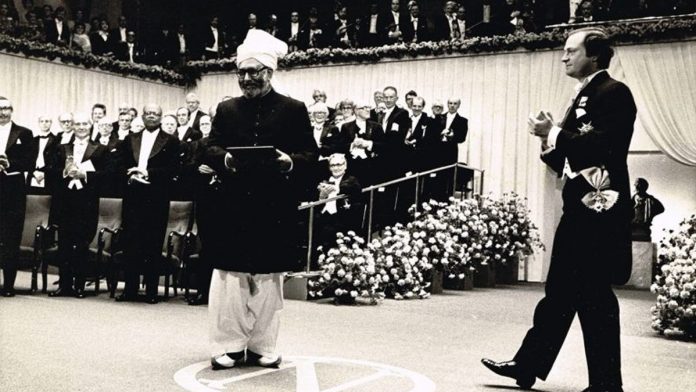

Nobel laureate Abdus Salam remains a controversial figure in Pakistan because of his Ahmadi faith. But now, my documentary will finally be seen where it matters most.

As Netflix releases my documentary Thursday on Pakistani physicist and Nobel laureate Abdus Salam, I recall how after the fifth screening of Salam – The First ****** (Muslim) Nobel Laureate at the Chicago South Asian Film Festival last September, a young woman approached me in the lobby. She was of Pakistani origin. She thanked me for making this film. I could see that the film had visibly moved her.

She had travelled a long distance to attend the screening. Her voice shaking with emotion, the woman confided in me that her father was killed in Pakistan when two Ahmadi mosques were attacked in Lahore in 2010. That’s when it dawned on me how important and iconic the story of Abdus Salam is to so many people in Pakistan and elsewhere.

Now, its Netflix release on 3 October will fulfill our singular goal of having this film seen widely in Pakistan and across the world — for people to know the journey of a man of science and religion who achieved great feats and was ostracized by his own countrymen.

The trigger

The making of this film has been a long an arduous journey, mostly championed by the steadfastness of its Pakistani-origin producers Omar Vandal and Zakir Thaver.

Omar Vandal is a senior scientist at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and Zakir Thaver is a science enthusiast and television producer. Both were colleagues on a US university campus when they decided to embark on a journey to make this film. Filmmaker Mira Nair recommended them to find a director to helm the project, and they found me through a mutual acquaintance.

When they approached me to direct it in 2016, they had already spent twelve years collecting archival material and raising funds by all means necessary.

Until then I had known very little about Abdus Salam. Having studied physics in my undergraduate years in college and directed another film about a physicist, I had known the name as he was from the sub-continent. But beyond that my knowledge about him was limited.

What instantly triggered my interest in the project was the complex and layered character of the “man” Abdus Salam. He was a child prodigy who came from a remote village and rose to great prominence purely on the basis of his intelligence and his ability to navigate the echelons of power and politics with charisma and tact.

Despite innumerable obstacles and Pakistan rejecting him for his faith, he seemed adept at navigating two worlds at every stage in his life. He reconciled the East and the West, the traditional and the modern, the religious and the scientific, the exiled and the citizen, without much conflict.

This drew me in as a filmmaker and storyteller and ignited my interest in exploring the contradictions and revealing the layers that make Abdus Salam a towering figure even today.

The distribution challenge

After a challenging year in the editing room, the documentary was completed in 2018. It had its first public screening at a science film festival in Santa Barbara, California, where it won the best film award. Since then, it has won several international awards, and has been screened at more than 30 cities across the world.

From Sri Lanka to the Czech Republic to Holland to India, wherever we have screened the film, it has moved people to tears and inspired many. The response has been overwhelming.

Despite its success at many international film festivals, it was a challenge to get the film distributed, either via a broadcast medium, theatrical release or a streaming platform. Many attempts were made to get an American distributor, but there were no takers. Even many A-list film festivals rejected the film, probably because the story was not “western”, “American” or “edgy” enough.

I sometimes used to make a snide comment when addressing an audience after a screening, saying that Salam was discriminated when alive and is still being discriminated against in death.

After almost a year of trying relentlessly, we approached Vista India, a Mumbai-based digital partner, which showed great interest in representing the film and eventually took it to Netflix.

Why Pakistan should watch the film

Unfortunately, due to the volatile political and religious climate in Pakistan, the one place the film would have the greatest significance did not get to see it widely.

But now with the Netflix release, this goal will be achieved, circumventing any censorship or blockade.

And we hope people in Pakistan will embrace this film and restore Abdus Salam’s stature and respect, which is long overdue. Abdus Salam remains a controversial figure in Pakistan for his Ahmadiyya faith. We hope our film will open eyes to see him beyond this aspect.

The violation of human rights of minority communities has continued unabated in the subcontinent. From our political leaders to common citizens, tribalism dominates people’s minds. Religion is used to divide and disenfranchise people on a regular basis. Right-wing nationalism and religious extremism creep into the minds of even the most educated and powerful — thus, sowing the seeds of hate and animosity among different communities.

As filmmakers, we know we cannot change the world with one film. We would be delusional and egotistical if we thought we could.

But what we can certainly do is provoke a discussion, shine light in darkness and force people to consider an alternative that is just and humane.

The producers of Salam are of Pakistani origin and I was born in India. Abdus Salam was born in British India, but eventually migrated and was laid to rest in Pakistan. People in both India and Pakistan carry the painful legacy of Partition.

Although India and Pakistan speak of war more than peace, we hope our small joint contribution to the world speaks of peace, science and humanity more than anything.

Abdus Salam once famously said, “Scientific thought and its creation are the common and shared heritage of mankind”. He said this at a time when the world was bogged down by the Cold War, and parochialism was at its most extreme. It showed that Salam was always thinking global.

This is the message I took away from his life. Science tells us we are much bigger than our differences and ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment