Alex Hern

Most of the world won’t be affected by the changes, so are they a problem? No, if you are a tech monopoly – but yes if you don’t want a two-tier internet.

Ajit Pai, head of the US telecoms regulator, revealed sweeping changes on Tuesday to overturn rules designed to protect an open internet.

The regulations, put in place by the Obama administration in 2015, enshrined the principle of “net neutrality” in US law. Net neutrality is the idea that internet service providers should not interfere in the information they transmit to consumers, but should instead simply act as “dumb pipes” that treat all uses, from streaming video to sending tweets, interchangeably.

Net neutrality is unpopular with internet service providers (ISPs), who struggle to differentiate themselves in a world where all they can offer are faster speeds or higher bandwidth caps, and who have been leading the push to abandon the regulations in the US.

On the other side of the battle are companies relying on the internet to connect to customers. Their fear is that in an unregulated internet, ISPs may charge customers extra to visit certain websites, demand fees from the sites themselves to be delivered at full-speed, or privilege their own services over those of competitors.

The fear is well-founded. Outside the US, where net neutrality laws are weaker and rarely enforced, ISPs have been experimenting with the sorts of favouritism that a low-regulation environment permits.

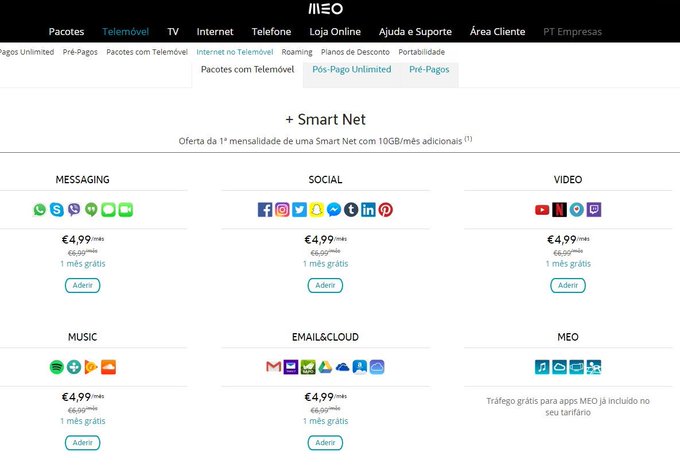

In Portugal, mobile carrier MEO offers regular data packages, but it also offers, for €4.99 a month, 10GB “Smart Net” packages. One such package for video provides 10GB of data exclusively for YouTube, Netflix, Periscope and Twitch, while one for messaging bundles six apps including Skype, WhatsApp and FaceTime.

In New Zealand, Vodafone offers a similar service: for a daily, weekly, or monthly fee, users can exempt bundles of apps from their monthly cap. A “Social Pass” offers unlimited Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter for NZ$10 for 28 days, while a “Video Pass” gives five streaming services – including Netflix but not YouTube – for $20 a month.

Even British carriers are experimenting. Virgin Mobile doesn’t charge extra for its packages, but does offer free data on three apps – Facebook Messenger, Twitter and WhatsApp – for subscribers. Three’s “Go Binge” plans do similar having “teamed up with Netflix, TVPlayer, Deezer, SoundCloud and Apple Music” to exclude them from data caps.

Two-speed internet

Supporters of net neutrality cite two major concerns about these practices. The first is that breaking the internet down into packages renders pricing confusing and difficult to compare, providing cover for mobile operators and ISPs to increase overall costs and pocket the difference.

The second is more systemic: an exclusive list of apps and services that receive preferential treatment divides the internet into haves and have-nots. Sometimes referred to as a “two-speed internet”, this runs the risk of entrenching incumbents at the top of the field, while making it very hard for startups to grow to the same scale. Consider, for instance, trying to advertise a new video-streaming service to New Zealand’s Vodafone customers. As well as beating Netflix on its own terms, perhaps by offering better programming or a cheaper subscription, the new service would have to deal with the fact that some Vodafone subscribers will get Netflix without affecting their data caps, but streaming from the startup will eat up their limit very quickly.

But if net neutrality is already weak around the rest of the world, without such negative outcomes becoming widespread, why has the US reacted so strongly – and negatively – to the changes domestically? A glance at Reddit, the self-proclaimed front page of the internet, reveals the scale of the response: 16 of the 25 stories on the site’s homepage are about net neutrality, with all but two of them linking to the exact same page. As San Francisco-based, British-born, venture capitalist Benedict Evans noted, the biggest distinction is competition. “When I lived in London I had a choice of a dozen broadband providers. That made net neutrality a much more theoretical issue,” Evans wrote. In the US, much of the population has essentially no choice over who to buy broadband from, with local monopolies enshrined in law and a nationwide duopoly providing access to high-speed connections for three quarters of the nation. That gives ISPs much more power to wield net neutrality in an extractive fashion, forcing customers to pay extra to access their favourite sites at full speed – or forcing companies to pay for access to customers. This back and forth has been going on for over a decade, with the term net neutrality coined in 2003, but in recent years the landscape has changed. The most obvious driver has been the election of a US President whose largest motivation for policy decisions appears to be simply undoing the actions of his predecessor.

But the power dynamics between the large internet firms and ISPs has also shifted, in a way that has lessened the institutional support for net neutrality.

In May 2017 Netflix CEO Reed Hastings, once one of the largest proponents of the principle, noted that it didn’t really matter for the firm anymore. “Neutrality is really important for the Netflix of 10 years ago, and it’s important for society, it’s important for innovation, it’s important for entrepreneurs … It’s not our primary battle at this point.

“[For] other people it is, and that’s an important thing, and we’re supportive through the industry association, but ... we don’t have the special vulnerability to it.”

If an ISP slows down the traffic to a small startup, that startup looks bad. If it slows down the traffic to Netflix, though, it’s the ISP that looks incompetent.

Other internet giants have an even weaker support for the principle. Facebook has actively contributed to the erosion of net neutrality in the developing world, through its Internet.org Free Basics programme. That offers free internet access, but only to a selected list of low-bandwidth websites (Facebook, naturally, is included). For the company that wants to ensure that all human communication is piped through its channels, whether or not other websites have good connections isn’t a great concern.

With the US regulations scrapped, the door is open for service providers to begin experimenting with their offerings. The new normal may go no further than those packages offered in the UK or New Zealand, or it may finally realise the nightmares the campaigners have been warning about all this time.

The fight now moves from the regulatory sector to the market: if ISPs try to introduce a two-tier internet, will consumers vote with their feet? Will they have the freedom to even do so?

No comments:

Post a Comment