By Niall Ferguson

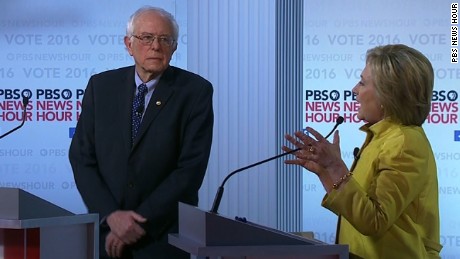

An intense confrontation between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders during Thursday’s debate centered on Henry Kissinger, a man who hasn’t held public office for 39 years. Kissinger, national security adviser and secretary of state for Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, won the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating the end of the Vietnam War and helped open relations between the United States and China. His advice has been sought by leaders of both political parties. But he has also been condemned for helping extend the war, spreading hostilities to Cambodia, supporting ruthless governments in Pakistan, Indonesia and Chile.

Does he deserve to be highly regarded or is he still a potent symbol of the abuse of American power?

For Bernie Sanders to call Henry Kissinger “one of the most destructive secretaries of state in the modern history of this country,” is a reminder that, for all his appeal to younger Democrats, Sanders is a throwback to a bygone era.

No secretary of state leaves office as a saint and nearly all strategic choices in the cold war were likely to be between evils.

Sanders’s gratuitous broadside against the 92-year-old statesman was calculated to hurt his rival Hillary Clinton, who has made no secret of her respect for Kissinger (not least in her recent review of his book "World Order").

But its historical content suggests that Sanders has not read anything published on the subject since the late Christopher Hitchens’s polemic, "The Trial of Henry Kissinger," which appeared 15 years ago — or perhaps since William Shawcross’s "Sideshow" (1979), the first book to blame Kissinger for the descent of Cambodia into the catastrophe of Pol Pot’s murderous tyranny.

Such works had a striking tendency to play down the roles of North Vietnam, the Soviet Union and China in the maelstrom of violence that engulfed Southeast Asia in the 1970s. Anyone who wants to pass judgment on the foreign secretaries of the cold war needs to bear in mind that the Communist states were ruthless aggressors on multiple occasions. Indeed, at the time Kissinger was appointed national security adviser at the end of 1968, the Soviets had reason to believe the Third World was going their way.

Hillary Clinton’s rejoinder to Sanders was that Kissinger’s “opening up China” and his “ongoing relationships with the leaders of China” had been and are “incredibly useful.” Certainly, any modern history of the Cold War today devotes significant space to the Nixon administration’s engagement with Mao’s regime, beginning with Kissinger’s secret visit to Beijing in 1971. Though fiercely criticized — by conservatives — at the time, it was one of the pivotal moments not just of the Cold War but of modern world history, exploiting the Sino-Soviet split, and laying the foundation for what I have called “Chimerica,” the key economic partnership of modern times.

Clinton could have countered with a longer list of Kissinger’s major achievements: the first strategic arms limitation treaty with the Soviet Union; the exclusion of the Soviets from the Middle East in 1973; the first steps toward peace between Israel and Egypt; not to mention the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, ignominious though it ultimately was. Above all, she might have reminded Sanders of the ultimate success of Kissinger’s policy of détente with Moscow, repudiated by Ronald Reagan only to be adopted by him at Reykjavík in 1986. Was Sanders against détente?

In another sally, Sanders sought to associate Kissinger with the “domino theory” during the Vietnam era. “Not everybody remembers that,” he declared. “The domino theory, you know, if Vietnam goes, China, da, da, da, da, da, da, da [sic].” However, the reason not everybody remembers this is because it is fiction. As I have shown, Kissinger had doubts about the Kennedy administration’s policy in Vietnam as early as 1963. He grasped the disastrous nature of the U.S. military effort in the course of a visit there in 1965. He spent much of 1967 trying vainly to initiate peace talks with Hanoi, despite his lack of sympathy with the Johnson administration, some members of which had indeed invoked the domino theory to justify their escalation of U.S. involvement.

No secretary of state leaves office with the record of a saint. As Kissinger himself observed before entering government, nearly all strategic choices in the Cold War were likely to be between evils. The moral challenge was to try to choose the lesser evil. That remains true in our time, which is presumably why Bernie Sanders would not discontinue the use of drone strikes in Pakistan and elsewhere. Nor would he terminate military aid to the Egyptian dictatorship of Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

Writing in 1968, Kissinger warned Americans against voting for leaders with “a high capacity to get … elected but no very great conception” of what to do in office. There is more than one of those around this year, unfortunately. They are not my kind of guys.

No comments:

Post a Comment