Altaf Hussain will never forget his 6-year-old daughter's first day of school on Dec. 16, 2014. Seven Taliban gunman attacked the Peshawar Army Public School in Pakistan’s unruly north, and killed the girl and 131 classmates. “Who knew that my daughter Khaula’s first-day at school will be her last day?" he lamented.

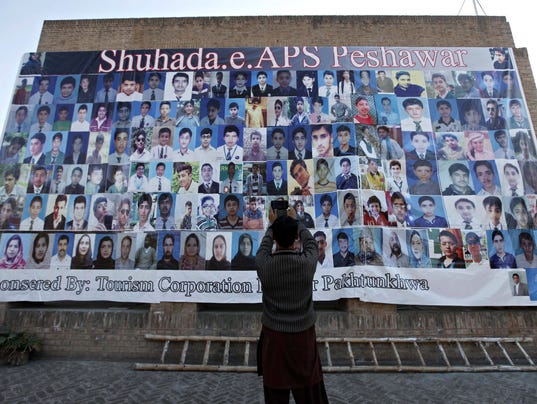

A year later, grief lingers over the loss of 141 people along with outrage over thePakistani government's failure to curb terrorist rampages that continue to plague the region.

Violence continues unabated along the Afghan-Pakistani border that Afghan and Pakistani Taliban fighters routinely cross, analysts say. Just this past Sunday, a bomb exploded in remote Parachinar, killing at least 23 people and wounding dozens more. Police arrested two Taliban suspects after the attack.

“Both Pakistani Taliban head Maulana Fazlullah and his leading commander, Omar Mansoor, are based in Afghanistan and are forever planning and executing new attacks,” said Rahimullah Yusufzai, a Peshawar-based expert on Afghan affairs. “The presence of the safe havens of the Pakistani militants in Afghanistan is an undeniable fact.”

After the school massacre, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif swore to crack down on the Pakistani Taliban fighters who staged the attack with a raft of measures that included lifting a seven-year moratorium on the death penalty for terrorism.

This year, authorities have hanged more than 300 people on terror-related crimes and other offenses, according to Amnesty International. Last week, the government put to death four terrorists charged in connection with the school attack and on Wednesday it executed eight convicted murderers.

Talat Masood, a retired lieutenant general and independent defense expert in Islamabad, said the military has succeeded in clearing militant sanctuaries in the northwest and forced some Taliban to flee.

But the police force and the judicial system remain very weak, he adds, and oversight of religious schools that teach extremism and mosques that preach militancy is practically non-existent.

Some critics say the government has used the death penalty to target political opponents instead of just extremists. “The end of the moratorium on the death penalty has resulted in more executions of non-terrorists than terrorists,” said Husain Haqqani, Pakistan’s former ambassador to the United States and a senior fellow at Hudson Institute, a think tank in Washington, D.C. "Several terrorist groups ...and the Afghan Taliban still flourish.”

Afghanistan has little reason to help Pakistan with the problem because Pakistani leaders aren’t controlling Islamic militants who plan their attacks in Pakistan and go across the border to target Afghan cities and troops.

The Afghan government in Kabul "has been countering Islamabad’s allegations on this point by pointing to the presence of the Afghan Taliban and Haqqani network leadership in Pakistan,” said Yusufzai.

Pakistani leaders are reluctant to crush Afghan terrorists on their territory because they hope the militants might become peaceful, join mainstream politics in Kabul and become Pakistan’s allies in the future, said Haqqani. Those leaders are misguided, he said.

“Attacking one group but hoping another will just become a political party means that we are allowing some Jihadis (warriors) to become dormant to fight another day,” said the former ambassador.

Failure to end the terror attacks infuriates Hussain, who taught at the Army school and was shot by gunmen as he tried to fight them. He was taken to a nearby hospital, where he learned of his daughter's death.

“A day doesn’t go by when I don’t think of Khaula,” he said. “I just wish I had got a chance to see her one last time.”

No comments:

Post a Comment