M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Tuesday, May 5, 2015

Pakistan - Which Musalmans do we claim descent from? By Ayaz Amir

By Ayaz Amir

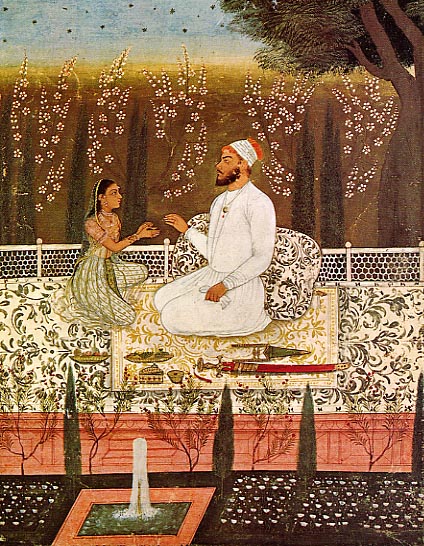

Muslim rule in Hindustan was mainly Turkish rule – from Mahmud to Babur all Turkish conquerors or rulers – interspersed with episodes of Afghan rule as under the Lodhis and Sher Shah Suri. But we the denizens of the Fortress of Islam – the confused begetters of holy enterprises like Jehad-e-Afghanistan – what have we in common with those warriors?

They were full-blooded men marching at the head of conquering armies…Muslims to be sure but with none of the false piety or hypocrisy which often seems to be the leading currency of our Islamic Republic. Come to think of it, none of them proclaimed their empires as Islamic Empires. Confident in the strength of their arms they felt no obligation or necessity to issue declarations about their rectitude or their championship of the faith.

The best or greatest of them were open about themselves. They maintained large harems, kept slave girls, married as often as they liked and when it came to imbibing, those given to this sin made no secret of it. With our weasel-like and snivelling ways – doing things behind doors and keeping up appearances in public – do we at all look like the descendants of Mahmud and Babur and Akbar?

What to talk of anything else, centuries before gay liberation came to San Francisco those inclined in that direction were fairly matter-of-fact about that too. So many times in his memoirs Babur referring to various chieftains or fighting men says of them that they had “vicious” tendencies – meaning to say that they were inclined to swing that way (although Babur uses words more direct than this).

Babur, however, is in a class by himself. Could ever a prince be more open about his foibles? We all know that the Babur-nama is full of references to drinking parties. Apart from being a warrior and a poet, Babur was an aesthete with a discerning regard for the finer things of life. Wherever he went, he planted gardens – I think it can quite justifiably be said that the father of the modern Hindustani garden is Babur. ‘I ordered a char-bagh to be laid…I ordered a platform to be built because the view from this spot was so wonderful to look at’: the memoirs are replete with such descriptions. And whenever a valley or a prospect catches the Padishah’s fancy he can’t resist a drinking party.

Or it could even be an occasion to partake of maajun, a favourite with this prince of princes. (I haven’t been able to find out whether maajun is from charas or opium.)

Sometimes these drinking parties go on for hours. The Padishah drinks at this chieftain’s place and then they move to the abode of some other companion. And so many times it happens that they march at the crack of dawn – Babur throughout calls it “shoot of dawn” – against a fortress or an opposing army. Tough men…the word hangover does not occur in these recollections.

And who can forget that famous passage about Babur’s infatuation when in Andijan (near Ferghana) for the bazaar-boy, Baburi. There is nothing to beat Babur’s own words: “In those leisurely days I discovered in myself a strange inclination, nay! as the verse says, ‘I maddened and afflicted myself for a boy in the camp-bazar, his very name, Baburi, fitting in….From time to time Baburi used to come to my presence but out of modesty and bashfulness, I could never look straight at him; how then could I make conversation (ikhtilat) and recital (hikayat)? In my joy and agitation I could not thank him for coming; how was it possible for me to reproach him with going away?...One day, during that time of desire and passion when I was going with companions along a lane and suddenly met him face to face, I got into such a state of confusion that I almost went right off. To look straight at him or to put words together was impossible…Sometimes like the madmen, I used to wander alone over hill and plain; sometimes I betook myself to gardens and the suburbs, lane by lane.”

Babur broke his drinking cups and forswore the use of wine before the battle against Rana Sangha at Kanwaha. But he keeps pining for what he has renounced. In a letter to Humayun: “…in truth the longing and craving for a wine party has been infinite and endless for two years past, so much so that sometimes the craving for wine brought me to the verge of tears…If had with equal associates and boon companions, wine and company are pleasant things; but with whom canst thou now associate? With whom drink wine?”

Is there anything in the culture, the mores and values of our republic in common with the sentiment expressed in these lines? We draw a direct line with the Timurids and say that we come from them. As we say in Urdu: chota moonh, barhi baat. Kahan woh, kahan hum. Bhutto made the admission in a public meeting that “mein thori see peeta hoon” and the maulvis and religious parties went after him. Would the Timurids have tolerated anything like our religious parties? Would they have countenanced any of their preaching?

Muslims ruled Hindustan for well over 600 years. During all this time did they feel the need to proclaim anything like the ideology of Islam? Did the Slave Kings or the Timurids fall back on anything like the Objectives Resolution?

They lived by the sword and when their sword-arm weakened their empire declined and from a master race they became a subject race. And Sir Syed Ahmed Khan in the days of their subjection and decline taught them the virtues of obedience: “…reflect on the doings of your ancestors, and be not unjust to the British Government to whom God has given the rule of India; and look honestly and see what is necessary for it to do to maintain its empire and its hold on the country.” Pakistan was born out of this milk-laced-with-water philosophy.

The spirit of Sir Syed, unless I am grossly mistaken, would be at home in Pakistan. Sir Syed would have been a great one for our pro-American alliances and for the Anglophilia of the chattering classes. But the spirit of Babur…it wouldn’t know what to make of the Pakistani scene or the Pakistani conversation.

Shouldn’t the Babur-nama be compulsory reading for all Pakistani students of history? The history we are taught is a distorted history, events and personalities painted in black-and-white and too many false gods and false heroes. What this history does above all is to make numb if not kill the critical faculty. You stop asking questions. You start accepting too many things on trust. You lay yourself open to the acceptance of outright nonsense.

Every society has its lunatic fringe. Every society has its share of rightward-leaning evangelists. But in societies where critical thinking is alive a fringe remains a fringe, part of the mosaic of society. It doesn’t become the bishop of the dominant discourse.

The Tablighi Jamaat is not peculiar to us. Something like it is there in every society, Christian, Hindu and Judaic. Our salvationists are of course adherents of Islam. Hindu salvationists do obeisance before their own deities. And Christian fundamentalists subscribe to their own creed. But in all three examples the rigid mindset is the same.

The Babur-nama would be prohibited reading in a madressah as it would be in a Christian seminary or a Hindu dharamsala. The priest as much as the mullah would feel ill at ease before words such as these: “A few purslane trees were in the utmost autumn beauty. On dismounting seasonable food was set out. The vintage was the cause! Wine was drunk! A sheep was ordered brought from the road and made into kababs. We amused ourselves by setting fire to branches of holm-oak…There was drinking till the Sun’s decline; we then rode off. People in our party had become very drunk…”

Is there anything in us worthy of this description? Would the Timurids recognise in us anything of their legacy? So why don’t we come down to more level ground? Why don’t we build a more prosaic, a slightly more rational republic, and leave the building of fortresses, whether of Islam or of ideology, to hands stronger than ours?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment