By Mark Lobel

We were invited to Qatar by the prime minister's office to see new flagship accommodation for low-paid migrant workers in early May - but while gathering additional material for our report, we ended up being thrown into prison for doing our jobs.

Our arrest was dramatic.

We were on a quiet stretch of road in the capital, Doha, on our way to film a group of workers from Nepal.

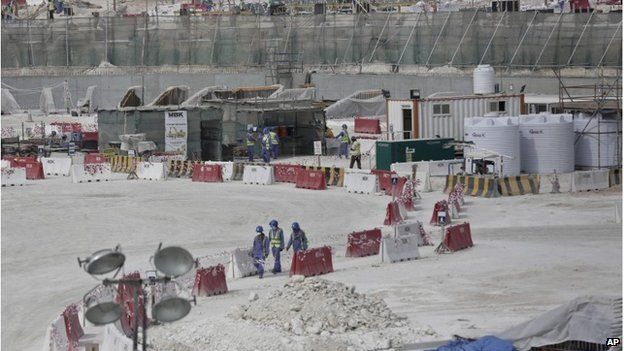

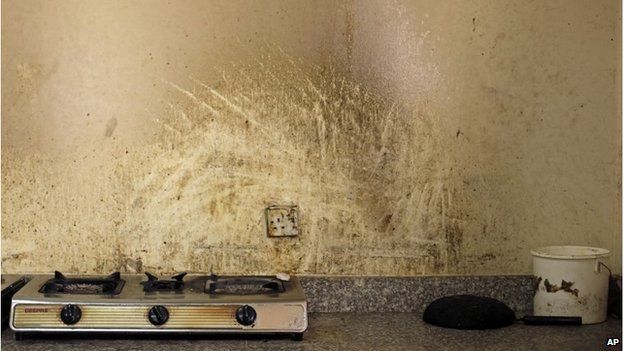

The working and housing conditions of migrant workers constructing new buildings in Qatar ahead of the World Cup have been heavily criticised and we wanted to see them for ourselves.

Suddenly, eight white cars surrounded our vehicle and directed us on to a side road at speed.

A dozen security officers frisked us in the street, shouting at us when we tried to talk. They took away our equipment and hard drives and drove us to their headquarters.

Later, in the city's main police station, the cameraman, translator, driver and I were interrogated separately by intelligence officers. The questioning was hostile.

We were never accused of anything directly, instead they asked over and over what we had done and who we had met.

During a pause in proceedings, one officer whispered that I couldn't make a phone call to let people know where we were. He explained that our detention was being dealt with as a matter of national security.

An hour into my grilling, one of the interrogators brought out a paper folder of photographs which proved they had been trailing me in cars and on foot for two days since the moment I'd arrived.

I was shown pictures of myself and the team standing in the street, at a coffee shop, on board a bus and even lying next to a swimming pool with friends. It was a shock. I had never suspected I was being tailed.

At 01:00, we were taken to the local prison.

'Not Disneyland'

It was meant to be the first day of our PR tour but instead we were later handcuffed and taken to be questioned for a second time, at the department of public prosecutions.

Thirteen hours of waiting around and questioning later, one of the interrogators snapped. "This is not Disneyland," he barked. "You can't stick your camera anywhere."

It was as if he felt we were treating his country like something to be gawped at, suggesting we thought of trips to see controversial housing and working conditions as a form of entertainment.

Qatari government statement, 18 May:

"The Government Communications Office invited a dozen reporters to see - first-hand - some sub-standard labour accommodation as well as some of the newer labour villages. We gave the reporters free rein to interview whomever they chose and to roam unaccompanied in the labour villages.

"Perhaps anticipating that the government would not provide this sort of access, the BBC crew decided to do their own site visits and interviews in the days leading up to the planned tour. In doing so, they trespassed on private property, which is against the law in Qatar just as it is in most countries. Security forces were called and the BBC crew was detained."

BBC response:

"We are pleased that the BBC team has been released but we deplore the fact that they were detained in the first place. Their presence in Qatar was no secret and they were engaged in a perfectly proper piece of journalism.

"The Qatari authorities have made a series of conflicting allegations to justify the detention, all of which the team rejects. We are pressing the Qatari authorities for a full explanation and for the return of the confiscated equipment."

In perfect English and with more than a touch of malice, he threatened us with another four days in prison - to teach us a lesson.

I began my second night in prison on a disgusting soiled mattress. At least we did not go hungry, as we had the previous day. One of the guards took pity on us and sent out for roast chicken with rice.

In the early hours of the next morning, just as suddenly as we were arrested, we were released.

Bizarrely, we were allowed to join the organised press trip for which we had come.

It was as if nothing had happened, despite the fact that our kit was still impounded, and we were banned from leaving the country.

I can only report on what has happened now that our travel ban has been lifted.

No charges were brought, but our belongings have still not been returned.

So why does Qatar welcome members of the international media while at the same time imprisoning them?

Is it a case of the left arm not knowing what the right arm is doing, or is it an internal struggle for control between modernisers and conservatives?

PR effort

Whatever the explanation, Qatar's Jekyll-and-Hyde approach to journalism has been exposed by the spotlight that has been thrown on it after winning the World Cup bid.

Other journalists and activists, including a German TV crew, have also recently been detained.

How the country handles the media, as it prepares to host one of the world's most watched sporting events, is now also becoming a concern.

Mustafa Qadri, Amnesty International's Gulf migrant rights researcher, told us the detentions of journalists and activists could be attempts "to intimidate those who seek to expose labour abuse in Qatar".

Qatar, the world's richest country for its population size of little more than two million people, is pouring money into trying to improve its reputation for allowing poor living standards for low-skilled workers to persist.

A highly respected London-based PR firm, Portland Communications, now courts international journalists. On the day we left prison, it showed us spacious and comfortable villas for construction workers, with swimming pools, gyms and welfare officers.

This was part of the showcase tour of workers' accommodation, and it was organised by the prime minister's office.

Qatar's World Cup organising committee, which answers to Fifa, was helping to run the tour.

Fifa says it is now investigating what happened to us. It has issued the following statement: "Any instance relating to an apparent restriction of press freedom is of concern to Fifa and will be looked into with the seriousness it deserves."

'Open country'

Following our detention, the minister of labour agreed to talk to us on camera about how the media can cover what human rights campaigners have identified as "forced labour" within his country.

"Qatar is an open country forever, since ever," Abdullah al-Khulaifi said.

"The shortcomings that I am facing, the problems I am facing, I cannot hide. Qatar is open and now with the smartphones, everyone is a journalist," he said.

He said the negative coverage of migrant workers' conditions was wildly overblown and that much progress had been made to improve basic conditions for migrant workers.

The government has implemented a wage protection scheme. It says at least 450 companies have been banned from working in the country and more than $6m (£3.8m) of fines have been handed out to firms mistreating workers, and the number of inspectors has been doubled.

Workers are now ferried to and from work in buses, not lorries.

But change has not come easily in what one security guard privately described to me as a country with surveillance officers everywhere.

Without trade unions or a free media, bosses of large domestic and international companies have little incentive to radically improve conditions for well over a million labourers desperate for money.

Before we were detained, I met an 18-year-old mechanic, one of the 400,000 Nepalese workers there.

He said he wanted to support his older brothers because his father had died and the family was struggling financially.

He paid a recruitment agency in Nepal $600 to arrange his visa to work in Qatar and was told he would earn $300 a month.

When he arrived he was told his salary, as a labour camp cleaner for air conditioning mechanics, was in fact $165 a month. He said he has never been given a copy of the contract he signed. Worse still, he said he could not understand it as it was in English.

It's a very common trick that foreign recruitment agents play before workers even get to Qatar, and very difficult for Qatar itself to police, although it says it is trying.

This young man now finds himself at the mercy of Qatar's restrictive kafala system, which prevents workers from changing jobs for five years. Being tied to an employer in that way can leave migrant workers open to exploitation.

However, with so much money needed for rebuilding decimated parts of Nepal, there will be no shortage of future volunteers.

And as Qatar's World Cup approaches, the focus on migrant labour is only likely to increase.

No comments:

Post a Comment