Emma Graham-Harrison

Despite 10 years of western efforts to curb production, a combination of economics and political instability means farmers in the world's largest heroin-producing country are as enthusiastic as ever for the poppy

Afghanistan's farmers planted a record opium crop this year, despite a decade of western-backed narcotics programmes aimed at weaning farmers off the drug and cracking down on producers and traffickers.

For the first time over 200,000 hectares of Afghan fields were growing poppies, according to the UN's Afghanistan Opium Survey for 2013, covering an area equivalent to the island nation of Mauritius.

Violence and political instability means there is unlikely to be any significant drop in poppy farming in the world's top opium producer before foreign combat troops head home next year, a senior UN official warned.

"This is the third consecutive year of increasing cultivation," said Jean-Luc Lemahieu, the outgoing Afghanistan director for the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, which publishes the report. "The assumption is that the illicit economy is to gain in importance in the future."With conflict spreading to once-peaceful areas of the country and a critical presidential election scheduled for early next year, poppy fields provide both cash to networks of power-brokers and insurance to farmers at the bottom of Afghanistan's feeble economy.

Portable and long-lasting, the high value per kilo of opium makes it attractive to families who fear they may need to flee, or see fields of conventional crops destroyed by fighting.

The total harvest was probably slightly lower than the previous peak five years ago, mostly because bad weather meant each plant yielded less of the sticky narcotic. But the number of fields turned over to poppy is a more accurate gauge of farmers' enthusiasm for the crop and the government's ability to control it than the final production figures.In a bleak assessment of efforts to curb opium farming in a country that produces the vast majority of the world's supply, Lemahieu said the international community needed to stop thinking there was a quick fix to a complicated problem. "As long as we think we can have short-term, fast solutions to the counter-narcotics problem, we are doomed to continue to fail," he said. "That means first knowing this will take 10-15 years."

Because the value of opium is so much higher than any other crop available to Afghan farmers, it has become the only way for many to cover the basic expense of large families. Although opium prices of around $130 per kilo are barely half their 2011 peak, they are still well above market rates after the last production glut of 2007, and may have further to fall. Many who grow the crop are aware that mullahs denounce production of the drug and the government bans it. But they say officials also grow the drug and religious leaders are always eager to claim a share of harvest income.

"We doubt that it is forbidden, because if it is, why are the mullahs taking these taxes?" said the 53-year-old farmer Abdul Khaliq, who has been growing poppy in Helmand province for over a decade to support a family of nearly two dozen. "We are a lot of people, this is the reason we grow opium. If we do other work, we can't feed our family."

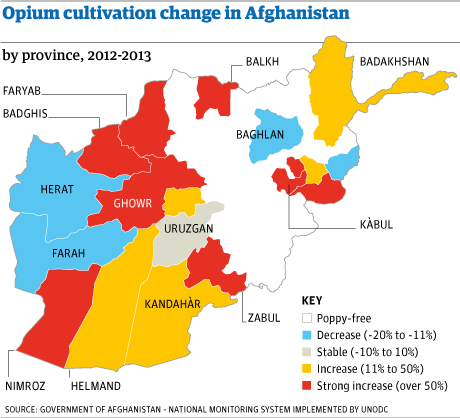

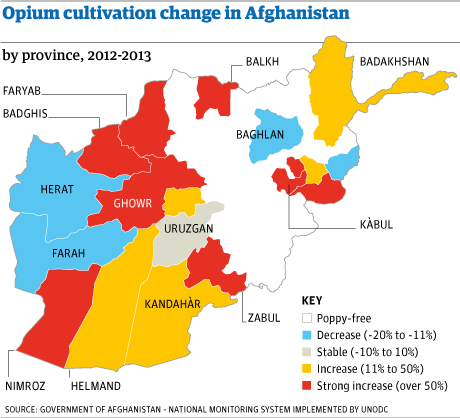

Around half the poppy grown in Afghanistan is planted in Helmand, and the end of a UK-backed project trying to keep poppy out of the main valleys, or "food zone", brought increase in planting there, though crop levels were far below that in areas under insurgent control, the report said.

"Opium cultivation in the food zone increased by half … [but] outside the food zone the extent of poppy cultivation was far greater," the report said.

Eradication efforts slowed and became much more dangerous, with 143 people killed while trying to uproot crops, up by nearly half from a year before. Nearly 100 others were injured.

Northern Badakhshan province was the only place in Afghanistan where authorities managed to destroy more than half of the poppy planted; elsewhere teams made small inroads to large harvests.

One of the few bright spots was greater control of the drugs trade, with beefed-up drugs police seizing over 10% of production, up from just 3% or 4% a few years ago, Lemahieu said. But the country also needs to work out how to tackle a growing addiction problem from a product that was once used largely for export or in moderation as a medication. Now over 1 million Afghans – around 3% of the population – have an opium or heroin habit.

Case study: the poppy farmer

My name is Hedayatullah, I am 45 years old and there are 11 people in my family. I am from Marjah district and I have been growing poppy for twenty years. No one in our family uses opium, we grow it as a business.

The imams often tell us it is forbidden to grow opium, but when we get our harvest they take a 10% tax. So we think they aren't saying these things because of religion and the holy Qur'an, other people are just telling them to say this.

We know the constitution says you can't grow opium but with wheat or beans you can't make good money. Also the government officials grow opium themselves, and if they don't grow it themselves they rent out their land to farmers who grow it. If the officials don't care about the law, there is no reason for us to respect it.

Under Taliban rule there was an order to stop growing opium, so I stopped for one year, but then the temporary government was set up and I started growing opium again.

In the government-controlled area we farm 1 jerib (half an acre) per year, but in the desert we farm another 4 to 5 jeribs. Sometimes the government does military operations, but after they leave the Taliban take back control.

Before I used to make 800,000 Pakistani rupees (£4,700) per year, but in the last two years it has gone down to 300,000 Pakistani rupees (£1,800).

No comments:

Post a Comment