M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Sunday, September 15, 2019

#Pakistan - The regime

Cyril Almeida

BY now, it’s apparent to all — or at least to anyone willing to look — what this is. Gone are the fig leaves and legal nuances and faux optimism. It is what it is, it isn’t very pretty and it’s probably going to get a whole lot uglier.

BY now, it’s apparent to all — or at least to anyone willing to look — what this is. Gone are the fig leaves and legal nuances and faux optimism. It is what it is, it isn’t very pretty and it’s probably going to get a whole lot uglier.

Welcome to the hybrid regime.

A lot has already gone wrong and the stuff that has gone wrong is obvious for two reasons. Economic hurt is impossible to hide, especially at the consumer end and when jobs start to disappear. Folk can easily intuit what’s going on every time they buy something or wander around in search of jobs.

Imran helped. His message was simple — I’ll fix everything at the same time in record time, just trust me — while the base he cultivated is simpler still: young-ish, previously apolitical and with not much understanding of much.

Outsized expectations were always going to collide with reality, but that reality has turned out to be so dismal and the collision come at such speed is down to something else.

Imran has landed himself in an awkward and potentially perilous situation.

The periodic shopping around for a useful idiot to nominally run the show was more straightforward in times past: pick a technocrat or select a traditional politician. Technocrats get a bit of work done because that’s what professional sorts do: they try and do stuff.

Never mind that they screw up matters and leave a mess behind; while they’re on the job, technocrats always look like they’re busy doing stuff. They have to.The traditional politician has much the same imperative to be seen to be doing things, but his focus is mostly on greasing the system because no grease means no support and no support means no utility to the ones hunting about for the next useful idiot.

But things aren’t so simple in a hybrid regime.

The headhunters don’t just have to find someone who can get things done, they need someone to bring a veneer of legitimacy to the whole enterprise. In these tricky times, a memorable Mohammed Hanif phrase must suffice by way of elaboration:

“Khan has politicised a whole generation, only to deliver it into servitude to Pakistan’s old establishment.”

If the headhunters needed someone Imran-esque, give the man his due: Imran made it impossible for the headhunters to look past him. A hybrid regime fronted by a technocrat or traditional politician was a non-starter in the presence of Imran.

With the idea being to put Nawaz and Zardari to the sword politically and then if you look past Imran too, there isn’t much left in the wagon wheel of public opinion from which to secure legitimacy for a hybrid regime.

One of the more curious elements of the experiment we’ve all been made to live through this past year is why this doesn’t seem to have occurred to Imran — that much as he needs them, they need him, or did anyway.

Perhaps Imran really has no interest in anything beyond becoming PM as a final chapter in a life well spent. Or perhaps in finding their latest useful collaborator the competence deficit is more than what had been hoped for.

Either way, in eviscerating great chunks of his political capital in little over a year, Imran has landed himself in an awkward and potentially perilous situation: on balance, it’s not quite clear if the veneer of legitimacy Imran brings to the hybrid regime is really worth the headaches he’s created for the regime.

But if what’s gone wrong is obvious and how we’ve got to this miserable point in double-quick time is fairly clear, there’s a more fundamental problem with the hybrid regime: it can’t work, no matter who is trotted out to front it.

Slice it anyway you like. Regimes almost by definition are a centralising force, but delivery is almost always decentralised.

Perhaps because the margins at the centre were razor-thin or perhaps because the impetus behind this project is itself a centralised force, too much time and attention was wasted on fashioning a workable arrangement at the centre.Imran is now effectively a lame duck at the centre, the IMF straitjacket and the snatching away of key ministries from his control ensuring that. But Imran still has real sway in Punjab and KP and, with the right assistance, a fair bit of potential to meddle in Sindh.That Imran has proved rubbish at managing the provinces, and thereby undercut the rationale of the hybrid regime, has obscured the point that the provinces can’t be managed from the centre. But then no regime can tolerate multiple power centres across the provinces. It’s a riddle with no solution.

Or flip it around.

Just because Imran is flailing around doesn’t automatically have to mean that a better frontman can never be unearthed. It could just be a question of more skilfully looking in the right place at the right time.

A regime frontman with the skills of a technocrat, the savvy of a traditional politician and the sleight of hand of a populist. See the problem there? In Pakistan? You may as well be looking for a unicorn snuggling up to leprechaun at the end of a rainbow. The internal contradictions of a hybrid regime are too many and too varied to be adequately and sustainably overcome.

By now, it’s apparent to all what this is: it isn’t very pretty and it’s probably going to get a whole lot uglier. And that we still have Imran is both the good news and the bad.

Pakistan, eh?

May God bless this land and good luck to all of us here.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1505305/the-regime

#Pakistan - Why Imran Khan's 'Kashmir Hour' Fell Flat

By Daud Khattak

To show solidarity with Kashmir, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan announced on August 26 that “Kashmir Hour” would be observed across the country. However, the common Pakistanis, unnerved by deteriorating security and economic conditions did not show much passion to honor the prime minister’s appeal.

Very few Pakistanis observed the much publicized “Kashmir hour” this past Friday, indicating a genuine source of concern both for Khan’s popularity and his Kashmir policy.

For decades, common Pakistanis in general and the religious right, continued to show an emotional attachment with the word “Kashmir”, and always claimed to render any sacrifice to make it a part of Pakistan. This is mainly because of state-sponsored propaganda and the use of fiery and jingoistic slogans in the social and political spheres of the country.

On August 26, Imran Khan in his tutorial-styled televised speech urged his countrymen and women to come out of their houses and workplaces every Friday and observe a thirty-minute “Kashmir hour” to show solidarity with the Kashmiri people. He said this should continue until September 27, when he would be addressing the United Nations General Assembly in New York.

While scattered protests were observed in major cities where traffic was stopped on red lights and political leaders, mostly from the ruling Tehreek-e-Insaaf party, led demonstrators on the first Friday on August 29, the response was lukewarm on September 6, the second Friday since Mr. Khan’s August 26 appeal.

Except for the country’s federal capital Islamabad, not a single major protest demonstration or a standstill was observed to mark the “Kashmir Hour.” Does this mean that Khan is losing his popularity?

He is famous for his angry posturing and emotional frenzies. In his speeches in the opposition, he termed the country’s previous leaders mainly Nawaz Sharif, as responsible for all the ills of the country. During his electoral campaign, Khan made tall claims of purging the country of corrupt practices, promising to recover looted money, to create job opportunities, to stop short of the International Monetary Fund for loans, to stabilize the economy, and to provide relief to the masses.

As the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf government completed its first year in July, none of the claims were materialized, as the country heads down to further economic and political instability. The prices of daily commodities, for example, have risen to their highest level in half a decade in March 2019, while the fiscal deficit for 2018-19 was 8.9 percent of the country’s GDP, which is the highest in four decades.

One of Imran Khan’s most ambitious plans was the creation of 10 million jobs within five years and construction of five million houses. However, unofficial estimates suggest unemployment and layoffs have risen mainly because of the economic slowdown and the record depreciation of the country’s currency.

And it is the poor and middle classes, who used to join Khan’s rallies, public meetings and protest sit-ins, who bear the brunt of his government’s policies. It is not unusual if there is no love lost for Imran Khan and his calling to arms among the masses any more.

Another reason for the feebler response to Khan’s “Kashmir Hour” is the almost muted reaction of the religious right and, in particular, of Kashmir-focused parties such as Jamaat-e-Islami and the now defunct Difa-e-Pakistan Council.

Religious and jihadi leaders are generally considered as the key drivers for the anti-America, anti-India, and pro-Kashmir policies of the country’s security establishment.

While relations between the religious parties and their backers in the establishment have already muddied following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States and Pakistan’s support for the Operation Enduring Freedom to topple the Taliban regime in Kabul, it further widened with the establishment’s not-so-secret support for Imran Khan’s party in the 2018 parliamentary elections.

Quite understandably, the religious parties then do not come out with the desired response when both Imran Khan and the security establishment need their street power.

People in mainland Punjab and the remote tribal areas, the two other strong support grounds for the country’s Kashmir cause, also did not stage protests the way they used to in the past.

While Punjab is undergoing its worst political divisions in some time following the imprisonment of three-time Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, the province’s most popular leader, on the basis of a highly controversial court judgement, the people of the tribal districts have recently expressed serious grievances regarding the huge human and financial losses they suffered during the military operations over the past 18 years.

And yet another reason for the muted response from the people is seen as a deliberate effort on part of the government and the security establishment to keep the Kashmir issue on the back burner for the time being mainly because the country is facing a multifaceted problem involving the terror funding and international pressure, dwindling economy and political instability.

The sword of Damocles will continue to hang over Pakistan until the country satisfactorily complies with the demands of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on money laundering and terror financing. Another tough front is U.S. President Donald Trump’s exit plan from Afghanistan by signing a peace deal with the Taliban, where Pakistan is being considered both a spoiler and a fixer.

In such testing times, letting jihadi groups and their sympathizers to demonstrate their street power like the past might have consequences.

Meanwhile, after drawing much ire of his detractors on the social media and in the parliament for mishandling the Kashmir issue, Imran Khan announced to address a public gathering in Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistan-administered Kashmir, on September 13.

Choosing Muzaffarabad as the venue for the prime minister’s speech, was meant to convey the message of Pakistan’s unwavering support for Kashmiris, but it also shows that he is no longer able to attract big gatherings in mainland Pakistan.

His political opponents are capitalizing on Imran Khan’s waning popularity when rumors of a deal between the government and imprisoned leader Nawaz Sharif are in the air.

Modi has finished Pakistan’s ‘unfinished business’ of Partition

SHEKHAR GUPTA

Article 370 is gone, now it’s time to fight the good fight — for rights of Kashmiris as fellow Indians and restoration of commerce & political activity in J&K.

Here is a somewhat different way of looking at Jammu and Kashmir today.

One side in the conflict had used one description for the Kashmir issue for 70 years, as if it was cast in a Pir Panjal rock: It is the unfinished business of Partition.

That side was Pakistan.

India never agreed. Not even by way of emphasising its claim on Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). India’s view was, Partition ended in 1947. We have moved on, so should you. It wasn’t stated, but unambiguously implied.

Pakistan disagreed. In the decade of the 1950s, it waited to strengthen its armed forces by joining US-led military pacts. That achieved, in the 1960s, it launched a full-fledged military campaign to take Kashmir by force to settle that “unfinished business”, but failed.

It spent the 1970s recuperating from defeat and the dismemberment of 1971. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto turned its attention westwards, towards Islamic countries, especially the Arabs, and sought solace in the Ummah. The “unfinished business” wasn’t forgotten. The Pakistani establishment was biding its time.

The time came in the late 1980s. By 1989-90, Pakistan believed it now had a proven strategy. It was the one used to defeat the Soviets in Afghanistan. It also had the nuclear umbrella. The asymmetric war launched in Kashmir at that time is now in its 30th year.

In the 1990s, it waned (after P.V. Narasimha Rao crushed the insurgency). It rose again with pan-Islamisation of the insurgency as foreign mujahideen surfaced. The intrusion in Kargil was the next gambit. That failed because of India’s resolute response and Pakistan’s non-existent international leverage.

After Musharraf’s coup in 1999, the insurgency was fully revived, now manned entirely by Pakistani jihadis. As it peaked, the Vajpayee government accepted a Pakistani overture for a summit. But the imperious manner in which Musharraf conducted himself at Agra shocked even an incorrigible peacenik like former prime minister I.K. Gujral. He said Musharraf was behaving as if he was visiting a “defeated country”.

The Agra summit failed. Pakistan’s global leverage also returned soon with 9/11. From being an expendable old ally-turned-nuisance, Pakistan emerged as a “stalwart ally” (Bush’s description) yet again. Bloodshed in Kashmir peaked. You want to know how strong Pakistan’s hold on the Americans was in this year? When Kashmir’s first suicide bomber blew up its state assembly, then Secretary of State Colin Powell infamously described it as an attack on an Indian government “facility”.

The attack on Parliament, a near-war following it, and then the long peace process with Musharraf during the tenures of Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh are relatively recent history. Regrettably, the Pakistani establishment was again only buying time.

Keeping pace with all the peacemaking efforts was pro-active asymmetric warfare. India was hit with something big the moment the ISI calculated India had had “too long” a period of respite. There were many train bombings, attacks here and there in mainland India (besides routinely in Kashmir) and then the Mumbai massacres of 2008.

The pattern continued in the following decade. Every thaw was followed by a kick in India’s shin. Gurdaspur, Pathankot, Pulwama, keep counting.

India responded in a variety of ways: From counter-insurgency in Kashmir, a localised fight back (Kargil), coercive diplomacy (after the Parliament attack) and strategic restraint (26/11).

The initiative was always with Pakistan. For 70 years, Pakistan had brainwashed itself into believing that if it kept bleeding India, India would one day give in.

Pakistan had given up hope of winning Kashmir after its 1965 misadventure. But there was always the hope for something, at least a face-saver, something to write home about.

From a four-district Valley land grab deal in the pre-1965 Bhutto-Swaran Singh negotiations under big-power (mostly British) pressure, to open borders and treaty-bound Kashmiri autonomy in the Musharraf-Vajpayee/Manmohan Singh era, Pakistan had moderated its expectations.

But it was confident of getting “something” in the end. Something to claim that it had concluded that unfinished business of Partition.

Instead, on 5 August this year, the Modi government finished that “business”. Every Indian prime minister had moved the clock in the same direction. Article 370 and Kashmiri special status and autonomy had been whittled down over these decades, as if serendipitously.

Narendra Modi has sealed that. Of course, it brings him great benefit in domestic politics. But he never claimed he wasn’t a politician.

This business finished, where do we go next?

For the first time since 1947, Pakistan has to strategise when it doesn’t have the initiative. India has shut the door on negotiations on the status of Kashmir, or at least the part of Jammu and Kashmir with India.

Pakistan can, of course, try to take it by force again. A full-fledged war will have its own consequences. Resumption of terrorism will be countered under the definition of a new normal.

Here’s the oldest reality on Kashmir: It was never an international or even bilateral issue. The only thing bilateral was our mutual hypocrisy.

For Pakistan, it was the fraudulent pretence of “Azad Kashmir”, as if “azadi” or any third option was available besides India or Pakistan.

For India, it was the insincere subterfuge of a moral, political and constitutional commitment to Kashmiri autonomy and special status. None of our 13 prime ministers believed this. Not even Jawaharlal Nehru.

All this is now buried.

The new reality is, therefore, essentially the old one: There will be no territorial exchange at all between the two countries, even if they fight a thousand-year war as Bhutto had threatened (only 72 have gone yet). Not even if they drop all their nukes on each other. Kashmir’s territorial status was never going to change. Now even cosmetic, optical face-savers to Pakistan are out.

There is a nuttier (but self-destructively powerful) section among the Pakistani establishment which still has scriptural belief of ‘Ghazva-e-Hind’, whereby Islamic forces led by them will “break up and subjugate India”. That is exactly the fantasy echoed by the idiotic few (and we don’t yet know who) who shouted “Bharat tere tukde honge…” the other day. India isn’t about to break up, and Kashmir will stay where it is.

Pakistan is out of the equation now. Where do we go next?

First, accept that whether or not you like Narendra Modi and Amit Shah, there is zero popular support for or prospect of what happened on 5 August being reversed. Zero. On the status of Kashmir, there is the widest political and popular unanimity in India.

This accepted, junk all guilt and self-flagellation. Since you swear by your Constitution, read it from Article 1 on, not 370. Article 1 lists the states and territories of India and has Jammu & Kashmir firmly at no. 15. You can’t swear by your Constitution, but only by a solitary temporary Article 370 and fight with its Article 1.

What follows is less cluttered. Speak, campaign, fight for the restoration of all civil and human rights, restoration of communication, commerce, movement, assembly, peaceful protests, political activity in Jammu and Kashmir. It’s a good fight.

Fight for the Kashmiris’ constitutional rights now as equal, fellow Indian citizens. There is no reason why they should not have the same rights as Indians in Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal or Gujarat. It should have always been the case, except for those lingering uncertainties about the “dispute” with Pakistan, the unfinished business of Partition.

After the loss of more than 42,000 lives in 30 years, a new history has begun in Kashmir. We can make it much better than the past.

بھارت سے تجارتی پابندیوں کے بعد نصابی کتب کا بحران سر پہ موجود

چونکہ پاکستان میں پرنٹنگ کا کاروبار نہ ہونے کے برابر ہے اس لیے یہاں صرف لوکل شاعری یا ادب کی کتابیں پرنٹ ہو جاتی ہیں لیکن یونیورسٹی پریس گروپ یا ہارورڈ پبلشر کی کتابیں بھارت میں ہی پرنٹ ہوتی ہیں۔

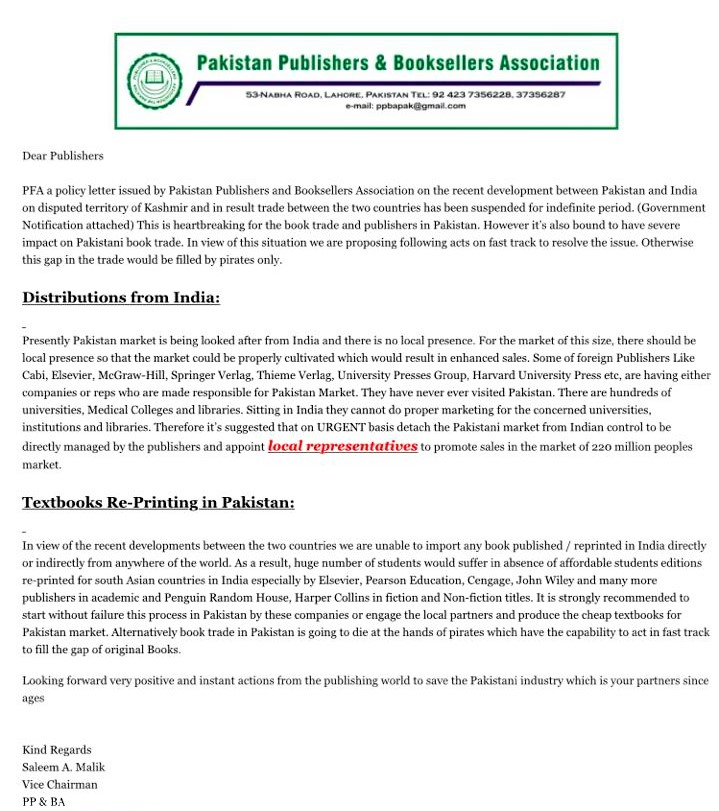

پانچ اگست کو بھارت کی جانب سے جموں و کشمیر کی ریاستی حیثیت ختم کرنے کے ردعمل میں پاکستان نے نو اگست کو بھارت کے ساتھ تجارت پر پابندیاں عائد کر دیں۔ پابندی لگنے کے تین ہفتے بعد ہی احکامات میں ترمیم کرتے ہوئے بھارت سے ادویات اور طبی آلات منگوانے کی اجازت دے دی گئی۔

یہ پابندیاں بھارت سے منگوائی گئی نصابی کتب پر کس طرح اثر انداز ہوتی ہیں، یہ جاننے کے لیے انڈپینڈنٹ اردو نے پاکستان پبلشر اینڈ بُک سیلر ایسوسی ایشن کے نائب صدر سلیم ملک سے بات کی تو انہوں نے بتایا کہ ’ٹیکسٹ بُکس جو بھارت سے پاکستان منگوائی جاتی تھیں وہ آئندہ تعلیمی سال اس پابندی کی وجہ سے میسر نہیں ہوں گی جس سے طلبا کا بہت نقصان ہو گا۔‘

انہوں نے مزید وضاحت کی ’بہت سی امریکی اور غیر ملکی پبلشر کمپنیوں نے جنوبی ایشا میں کتابوں کی مناسب قیمت رکھنے کے لیے بھارت میں اپنے پبلشر ہاؤسز بنائے۔ وہاں او لیول، اے لیول، میڈیسن، انجنئیرنگ اور کمپیوٹر سے متعلقہ کتابیں چھاپی جاتی ہیں اور جنوبی ایشا کے دیگر ممالک میں ان کی ترسیل کی جاتی ہے۔‘ انہوں نے کہا کہ نو اگست کے تجارتی بندش نوٹیفیکیشن کے بعد پاکستان اب بھارت سے وہ کتب بھی درآمد نہیں کر سکتا۔

جب اُن سے سوال کیا گیا کہ کیا پاکستان میں ان بین الاقوامی ٹیکسٹ بُکس کا سٹاک موجود نہیں تو سلیم ملک نے کہا کہ موجودہ تعلیمی سال کے لیے کتابیں تو طلبا نے خرید لی ہیں لیکن آنے والے دسمبر جنوری میں شروع ہونے والے سمسٹر اور تعلیمی سال کے لیے کتابوں کا ذخیرہ موجود نہیں اور اس کے لیے حکومت کو اقدام اٹھانے ہوں گے۔

کیا وہ کتابیں پاکستان میں پرنٹ نہیں ہو سکتیں؟ اس سوال کے جواب میں انہوں نے کہا کہ ’پاکستان کے پاس پرنٹ کرنے کے قانونی حقوق نہیں ہوں گے تو ہم پرنٹ نہیں کریں گے۔ اور بغیر اجازت اگر کتابیں پرنٹ کی جائیں گی تو وہ قانونی خلاف ورزی میں شمار ہو گا۔‘

سلیم ملک نے کہا کہ ’ہم نے بین الاقوامی پبلشر سے درخواست کی ہے کہ اگر 2000 سے زائد کتابوں کی سالانہ ضرورت ہے تو پاکستان کو وہ کتابیں پرنٹ کرنے کے قانونی حقوق دیے جائیں۔‘

انہوں نے کہا ’چونکہ پاکستان میں پرنٹنگ کا کاروبار نہ ہونے کے برابر ہے اس لیے یہاں صرف لوکل شاعری یا ادب کی کتابیں پرنٹ ہو جاتی ہیں لیکن یونیورسٹی پریس گروپ یا ہارورڈ پبلشر کی کتابیں بھارت میں ہی پرنٹ ہوتی ہیں۔ وہاں سے پاکستانی پبلشر وہ کتابیں منگوا کر بڑے کتاب گھروں میں تقسیم کر دیتے ہیں جہاں سے طلبا کتابیں خرید لیتے ہیں۔ لیکن جب مارکیٹ میں کتابیں میسر ہی نہیں ہوں گی تو طلبا کتابیں کہاں سے خریدیں گے؟ ‘

انہوں نے مزید کہا کہ ’اگر پاکستان کو پرنٹنگ کے حقوق مل جائیں تو اس سے پاکستان میں پبلشنگ بزنس بھی بڑھے گا اور روز روز کے پاکستان بھارت تناؤ سے درسی کتابوں کی تجارت میں بندش بھی نہیں آئے گی۔‘

اگر ادویات کی درآمد کی اجازت دے دی گئی ہے تو کتابوں کی درآمد کی بھی اجازت حکومت کو دینی چاہئیے۔ اس معاملے کی وضاحت کرتے ہوئے سلیم ملک نے کہا کہ 'ہم پبلشرز کے ساتھ رابطے میں ہیں اور ہماری پہلی کوشش یہی ہے کہ اس مسئلے کا مستقل حل نکال لیں اور پاکستان میں پرنٹنگ کے حقوق حاصل کر لیں۔ انہوں نے کہا کہ حکومت نے 70 برس سے اس بارے میں کچھ نہیں کیا۔ اتنی اہم کتابیں پاکستان میں پرنٹ ہونا شروع ہو جاتیں تو دہلی سے درآمد کرانی ہی نہ پڑتیں۔ لیکن افسوس کہ تعلیم کو کبھی اتنی توجہ دی ہی نہیں گئی۔

انہوں نے کہا کہ ’حکومت سے یہی اپیل ہے کہ اس مسئلے کا مستقل حل نکالے اور پاکستان میں بین الاقوامی کتابوں کے پرنٹنگ حقوق لینے میں پبلشرز کی مدد کرے تاکہ ہم اہم تعلیمی کتابوں میں خودکفیل ہو سکیں۔‘

وزیر تعلیم شفقت محمود سے انڈپینڈنٹ اردو نے رابطہ کیا تو انہوں نے کہا کہ 'معاملہ وزارت تجارت دیکھ رہی ہے لیکن وہ خود بھی اس معاملے کو دیکھیں گے کہ درسی کتابوں کے معاملے پہ حکومت کیا کر سکتی ہے۔‘

درسی کتابوں کا مسئلہ کیسے حل ہو؟ یہ جاننے کے لیے انڈپینڈنٹ اردو نے وزارت تجارت کے ترجمان محمد اشرف سے رابطہ کیا تو انہوں نے بتایا کہ ’ابھی تک حکومت کے علم میں یہ معاملہ تھا ہی نہیں اور نہ ہی کسی بھی پبلشر ایسوسی ایشن کے رکن نے وزارت تجارت سے رابطہ کیا ہے۔‘

وزارت تجارت کے ترجمان نے کہا کہ ’پبلشرز اگر حکومت کے پاس باضابطہ پروپوزل لے کر نہیں آئیں گے تو مسئلہ کیسے حل ہو گا؟ جب بھی دو ملکوں کے درمیان تجارتی پابندیاں لگتی ہیں تو دونوں ممالک میں بزنس کمیونٹی کو برداشت کرنا پڑتا ہے۔ لیکن یہاں اہم بات یہ ہے کہ وزارت تجارت کو تو خوشی ہو گی اگر پاکستان کو بین الاقوامی پبلشرز سے حقوق ملیں اور یہاں ری پرنٹنگ کی سہولت مل جائے۔ اس سے پرنٹنگ انڈسٹری بھی ترقی کرے گی لیکن اس کے لیے متعلقہ پاکستانی پبلشرز کو معاملہ وزارت تجارت کے سامنے رکھنا ہو گا۔ صرف بیان میں یہ کہہ دینا کہ حکومت کچھ نہیں کر رہی، اس سے مسائل کا حل نہیں ہوتا۔‘

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)