By Mohammed Hanif

This country has a poor record of protecting its religious minorities, but we outdo ourselves when it comes to Ahmadis. Members of the sect insist on calling themselves Muslims, and we mainstream Muslims insist on treating them like the worst kind of heretics.

The day I wrote this piece, a small headline in a newspaper informed me that an Ahmadi lawyer, his wife and two-year-old child had been shot dead by gunmen at home, for being Ahmadis. Killings like this have happened so many times that the story wasn’t even the main news. On May 28, 2010, some 90 Ahmadis were killed during attacks on two mosques in Lahore. No public official attended the funerals.

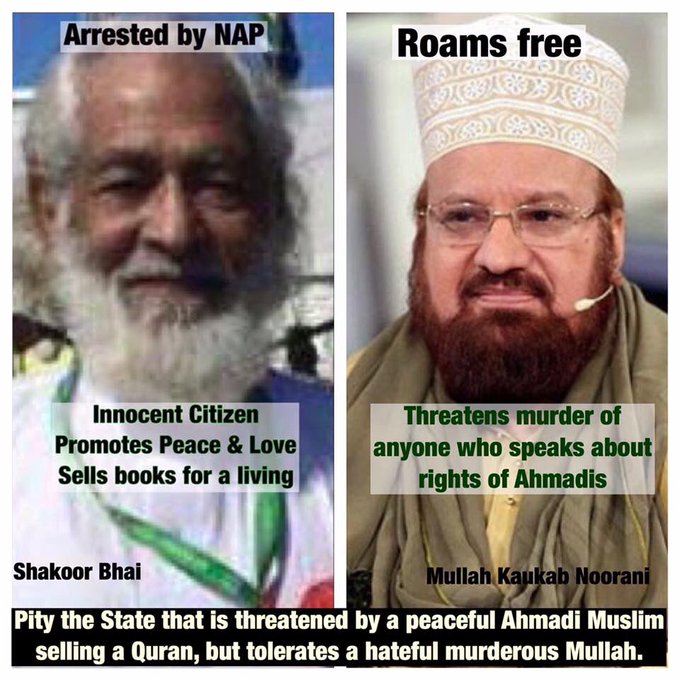

You would think that the government, law enforcers and the courts would do something about such sustained acts of brutality. But they are too hard at work. I learned from another recent headline that a district court near Lahore, in eastern Pakistan, had sentenced three Ahmadi men to death for blasphemy. A fourth man was shot dead before the trial while in police custody.

It is always prudent not to ask what blasphemous act is said to have been committed, because under the law, repeating something blasphemous can itself constitute blasphemy. According to one newspaper report, the men were on trial for attempting to remove from a wall religious posters that incited hatred against Ahmadis. That’s right, they were sentenced to death for taking down posters that incited people to kill them. (The prosecution argued that since the posters were religious, removing them was an insult to the Prophet Muhammad.)

The Ahmadi (or Ahmadiyya) sect is a reformist movement founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad toward the end of the 19th century in the city of Qadian, in what is today the Indian part of Punjab. Ahmad claimed to be the incarnation of a Messiah promised in Islamic holy texts. That challenged the mainstream Muslim belief that Muhammad is Islam’s last and final prophet. Ahmad was accused of being an agent of the British Empire.

There are no reliable statistics about the number of Ahmadis in Pakistan today. Many Ahmadis don’t publicly identify as Ahmadi; others refuse to take part in the census. Estimates range from 500,000 to four million.

In 1974, Pakistan’s elected Parliament declared Ahmadis to be non-Muslims. Religious parties had held street protests demanding this, and even though Parliament back then was full of liberals and socialists, there was hardly a dissenting voice when the time came to pass the law.

Our Parliament today is still at it. Last week Muhammad Safdar, a son-in-law of the recently deposed prime minister, thundered against Ahmadis, demanding they be banned from joining the armed forces. He also demanded that a physics department of a university in Islamabad be renamed because in 2016 it was named after Abdus Salam, the only Pakistani scientist to become a Nobel laureate. The Pakistani government had already taken close to four decades to name anything after Mr. Salam, a theoretical physicist, because he was Ahmadi. It appears that not a single parliamentarian spoke up against Mr. Safdar’s diatribe.

Earlier this month, Parliament also changed the oath that Pakistanis are required to take to get a passport or run in an election. A standard version of the statement goes: “I hereby solemnly declare that I consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Qadiani to be an impostor nabi and also consider his followers, whether belonging to the Lahori or Qadiani group, to be non-Muslims.” (Nabi means prophet.) Language in the election law was changed from “I solemnly declare” to “I believe.”

It’s not clear why this happened. The government claims it was a clerical error. But there was a public uproar over the change, including accusations that the government was going soft on Ahmadis. Parliament promptly backtracked, and we all resumed solemnly declaring rather than just believing.

The word “Ahmadi” was hardly even used during the debate in Parliament. We prefer to call the Ahmadis “Qadianis,” meaning from Qadian. Ahmadis consider the word derogatory, which is why we use it.

I got a call a few months ago from my family who still lives in my ancestral village in Punjab. A stranger had come asking about me, I was told. He claimed to be my friend from school. While I was still trying to put a forgotten face to the name, my relative asked, “Is your friend a Qadiani?” I suddenly remembered the boy from my school who was indeed a friend and happened to be Ahmadi. I asked the relative, “How did you know he was a Qadiani?” The reply shouldn’t have shocked me, but it did. “I have an inbuilt Qadiani detector. I can always smell them.”

I wanted to remind my relative that when I was a kid and he was a young man, all his best friends were Ahmadis and I had seen him locked in our bathroom smoking his first cigarette with those infidels. But then I remembered the slap.

It must have been around 1974. I was about nine years old and was taking my Quran lessons. My teacher was gentle. At the time, protesters in the bazaars were asking shoppers not to go to Ahmadi-owned shops. I asked my teacher who the Ahmadis were, and he patiently explained that they were heretics, because they challenged the notion that Muhammad was Islam’s last prophet. I said, even if they are heretics, does Islam say we can’t buy stuff from their shops? The slap was full and hard.

As I grew up, Ahmadis went from being treated as zealous reformist Muslims to non-Muslims to kafir, or heretics — worse even than Hindus or Jews. In the mid-1980s, a decade after Ahmadis were declared non-Muslims, another set of laws forbade them to act like Muslims.

This is the tricky bit, because Ahmadis insist on calling themselves Muslim and behave like Muslims. They pray in mosques, they call out the azaan at prayer time, they say “assalam alaikum,” they invoke Allah’s will or his mercy — and every time they do any of the above, they violate the law of the land. If they call their mosque a mosque, they become criminals. If they call their daily prayers namaz, as Muslims do, they risk imprisonment. Ahmadis have been charged with blasphemy for printing a verse of the Quran on wedding invitations.

Early this month, I saw Pakistan’s foreign minister, Khawaja Muhammad Asif, give an interview on television. He had just returned from a tour of the United States and had been accused of hobnobbing with Ahmadis while there. He was at pains to explain that he had never met an Ahmadi in his life. To prove his point, he said that once, while he was sitting in a restaurant in Islamabad, two boys came up to get a selfie with him. “I asked them, ‘I hope you are not Qadianis.’” The foreign minister and the show host shared a hearty laugh.

I

called up my long-lost Ahmadi friend recently and the brief conversation that followed was full of blasphemies. He was acting all Muslim. “Assalam alaikum,” he greeted me. By the grace of Allah, he said, he still has a job. Sometimes, when people suspect him of being Ahmadi, he is thrown out of shops or business meetings. But Allah is kind, my friend insisted. His wife, a teacher of fashion design, still has a job at a university — though she doesn’t use the staff room because some people have become suspicious. The kids are doing well, thanks to Allah, but he has told them not to tell even their closest friends that they are Ahmadis.

He tried to make us both feel better: Thanks to Allah, it’s not as bad for us as it is for Shias. Look how many of them get killed for their beliefs.

Pakistan was essentially created to protect the religious and economic rights of Muslims who were a minority before India’s partition in 1947. But since the country’s inception, we have created new minorities and keep finding new ways to torment them.