In this context, Pakistan has the fastest-growing nuclear program in the world. And as Koblentz says in a DW interview, by 2020, the Islamic Republic could have a stockpile of fissile material that, if weaponized, could produce as many as two hundred nuclear devices, roughly equivalent to the size of the United Kingdom's nuclear arsenal.

The only four countries currently expanding their nuclear arsenals are China, India, Pakistan and North Korea. Although each nation's buildup is motivated by different reasons, the combination makes Asia the center of a new nuclear arms race.

China has been increasing and diversifying its nuclear arsenal since the end of the Cold War. This buildup is part of a broader effort to modernize the Chinese military and is also motivated by advances in the US' military capabilities such as long-range precision strike systems and missile defenses.

Major developments include the introduction of road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles and a new generation of nuclear submarines armed with ballistic missiles. These new forces should significantly improve the survivability of China's strategic nuclear forces.

India and Pakistan's slow-motion arms race picked up speed in 1998 when both countries conducted multiple nuclear tests. The ensuing nuclear and missile buildup by both countries shows no signs of abating. Last month, Pakistan tested two missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads: the 900-kilometer range Shaheen-1A (Hatf-IV) and the 1,500-kilometer range Shaheen 2 (Hatf-VI).

Altogether, Pakistan has deployed or is developing eleven different nuclear delivery systems including ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and aircraft. India is also fielding an increasingly capable array of ballistic and cruise missiles to complement its nuclear-capable aircraft. Both states are also expanding their capacity for producing highly enriched uranium and plutonium, the two key materials needed to produce nuclear weapons.

North Korea is the newest member to the nuclear club. Although North Korea started with a much smaller base of nuclear and missile technology than China, India or Pakistan, it has exerted enormous effort to develop a nuclear warhead small enough to be delivered to the continental United States by a ballistic missile.

In your report you identify South Asia as the region "most at risk of a breakdown in strategic stability." Why is this the case?

South Asia is the region most at risk of a breakdown in strategic stability due to an explosive mixture of unresolved territorial disputes, cross-border terrorism, and growing nuclear arsenals. While the United States and Soviet Union were engaged in a fierce competition during the Cold War, India and Pakistan face more severe security challenges than those of the other nuclear weapon states. The status of the Muslim-majority province of Jammu and Kashmir in India remains a source of dispute between the two states. India and Pakistan have already fought three conventional wars since they gained independence in 1947, including two over Kashmir.

Koblentz: 'China's military buildup is partly motivated by advances in the US' military capabilities such as long-range precision strike systems and missile defenses'

Since their nuclear tests in 1998, India and Pakistan have fought one low-intensity war (the 1999 Kargil War) and experienced two serious crises spurred by terrorist attacks launched from Pakistan (the 2001 attack on the Indian Parliament and the 2008 Mumbai attack). The geographic proximity of the two countries complicates crisis management since the flight times of ballistic missiles is measured in minutes. Finally, while both states claim to seek only a credible minimum nuclear deterrent, regional dynamics have driven them to pursue an array of nuclear and missile capabilities.

In this context, how dangerous has the ongoing rivalry between India and Pakistan become?

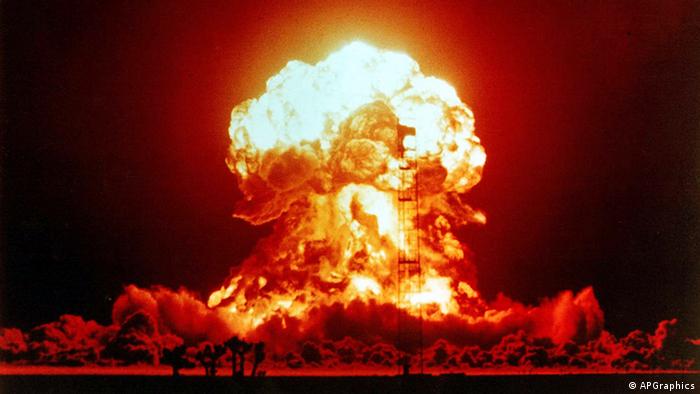

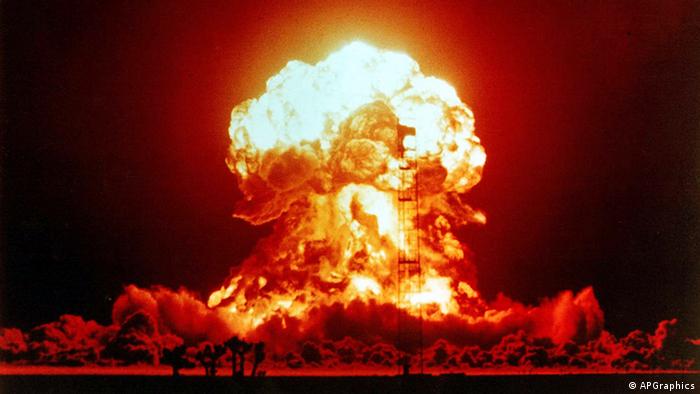

One of the most dangerous aspects of Indo-Pakistani rivalry is the introduction of tactical nuclear weapons in South Asia. During the next Indo-Pakistani conflict, the "fog of war" could take the shape of a mushroom cloud. After the 1999 Kargil War, India developed a new doctrine of rapid, limited conventional military operations designed to punish Pakistan but remain below Pakistan's presumed nuclear threshold.

In response, Pakistan has begun deploying tactical nuclear weapons, such as the Nasr (Hatf IX) short-range ballistic missile, to deter even limited Indian military intervention. Since the conventional military imbalance between India and Pakistan is expected to grow thanks to India's larger economy and higher gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate, Pakistan's reliance on nuclear weapons to compensate for its conventional inferiority will likely be an enduring feature of the nuclear balance in South Asia.

One of the most worrisome risks introduced by Pakistan's deployment of tactical nuclear weapons, especially acute during a crisis, is what Scott Sagan calls the "vulnerability/invulnerability paradox."

Pakistani nuclear doctrine calls for the deployment of road-mobile missiles during a crisis to protect them from an Indian first strike. But these weapons will become more vulnerable to theft or terrorist takeover once they leave the security of a military garrison.

The risk that terrorists could breach Pakistan's nuclear security is magnified by the strong presence of domestic extremists and foreign jihadist groups in Pakistan, their demonstrated ability to penetrate the security of military facilities, and evidence that these groups have infiltrated the Pakistani security services.

Another worrisome development is that the Pakistani practice of storing its nuclear warheads separately from launchers, which has provided a strong barrier to nuclear escalation in the past, may be eroding. The introduction of tactical nuclear weapons may lead Pakistan to loosen its highly centralized command and control practices. Due to their short-ranges (the Nasr/Hatf-IX has a range of about 60 kilometers), these types of weapons need to be deployed close to the front-lines and ready for use at short-notice.

Granting lower-ranking officers greater authority and capability to arm and launch nuclear weapons raises the risk of unauthorized actions during a crisis. Another risk is inadvertent escalation. There is the potential for a conventional conflict to escalate to the nuclear level if the commander of a forward-deployed, nuclear-armed unit finds himself in a "use it or lose it" situation and launches the nuclear weapons under his control before his unit is overrun.

How fast is Pakistan's nuclear weapons' stockpile growing?

While there are significant uncertainties about the scope and sophistication of Pakistan's nuclear weapon program, the country appears to have the most aggressive program in the world for producing nuclear material for military purposes. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Pakistan currently has enough fissile material, in the form of highly enriched uranium and plutonium, for about 100-120 nuclear weapons.

However, Pakistan is expanding its capability to produce even more weapons-grade material. By 2020, it could have sufficient weapons-grade uranium and plutonium to manufacture more than 200 nuclear weapons, roughly equivalent to the size of the United Kingdom's nuclear arsenal.

Although Pakistan initially focused on the uranium route to nuclear weapons, in recent years it has focused more on the plutonium pathway. Pakistan currently has three reactors at the Khusab nuclear site, 200 kilometers south of Islamabad, capable of producing enough plutonium for six to seven nuclear weapons a year.

In addition, Pakistan is constructing a fourth reactor at this site and expanding its ability to reprocess the spent fuel from these reactors to obtain additional plutonium. Once all four reactors and associated reprocessing facilities are complete, Pakistan will be able to produce an estimated 10-12 bombs-worth of plutonium a year.

Where is Pakistan getting the material it needs to develop these weapons?

Pakistan has a well-developed covert procurement network to obtain the materials it needs to fuel its nuclear and missile programs. During the 1970s, the Pakistani metallurgist Abdul Qadeer Khan obtained critical information about centrifuges being developed by the Anglo-Dutch-German consortium URENCO. Khan used his personal contacts and a list of URENCO's European suppliers to obtain vital material for the uranium enrichment program for several decades.

China also provided important assistance in the early 1980s in the form of highly enriched uranium and the design for an early-generation nuclear weapon. China has also been the source of key technologies (such as ring magnets) for the centrifuge program and for the construction of the Khusab plutonium production reactors. The Institute for Science and International Security has also documented a number of recent cases of American, Pakistani, Chinese, and Israeli citizens violating US export control laws by attempting to ship dual-use materials to Pakistan.

Koblentz: 'During the next Indo-Pakistani conflict, the 'fog of war' could take the shape of a mushroom cloud'

Are there any international attempts or strategies to halt the nuclear arms build-up in the region?

The nuclear and missile arms race in South Asia has not received the same level of international concern as developments in Iran or North Korea. The US tried to prevent arms racing between India and Pakistan after their 1998 nuclear tests but that effort fell to the wayside as other issues gained higher priority.

The terrorist attacks on September 11 and the US invasion of Afghanistan pushed nuclear issues low down on the list of important issues in US-Pakistani relations. Similarly, the rise of China and the potential for greater economic relations eclipsed nuclear weapon issues in US relations with India.

What is your forecast for the region for the next 5 to 10 years in terms of security and the development of nuclear weapons?

Unfortunately, I think that South Asia will remain at high risk for a nuclear crisis of some sort for the next five to ten years. Kashmir will continue to be a source of conflict between India and Pakistan. That territory has existential implications for both countries and will not be resolved in the foreseeable future.

Although Pakistan experienced its first democratic change of government in 2013, the country's history of military coups will limit the ability of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and his successors to challenge the authority of the military establishment on defense and foreign policy issues.

In addition, elements of the Pakistani government, such as the Inter-Service Intelligence agency, actively resist efforts at rapprochement with India. At the same time, India has not gone out of its way to assuage Pakistan's sense of vulnerability to its much larger and richer neighbor or pursue confidence-building measures that could reduce nuclear risks on the subcontinent.

The next crisis between India and Pakistan could be sparked by a cross-border military incursion, a mass-casualty terrorist attack, or a high-profile assassination. The growth of nuclear and missile capabilities on the subcontinent since 1998 has increased the risk that such a crisis could escalate in unforeseen and dangerous ways.

As India and Pakistan deploy new nuclear forces, such as cruise missiles, tactical nuclear weapons, and sea-based nuclear missiles, new challenges to crisis stability, deterrence, and command and control will arise. If India and Pakistan don't change their current trajectory, a nuclear crisis, or even worse, is likely to occur.

Gregory Koblentz is an Associate Professor in the School of Policy, Government and International Affairs at George Mason University and author of the Council on Foreign Relations report, "Strategic Stability in the Second Nuclear Age."

.png)