M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Friday, January 2, 2015

The Fear That Haunts Peshawar

By Abdur Razzaq

After the Taliban killed 147 people at a local school, 136 of them children, nobody in Pakistan's frontier city feels safe

Two weeks after a Taliban attack on a local school killed 147 people, 136 of them children, the Pakistani city of Peshawar is still raw with grief and fear.

But the Dec. 16 attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar surpassed even those standards of horror. It was the worst single terrorist attack in the history of a country that, according to the Global Terrorism Index, is the world’s most affected by terrorism after Iraq and Afghanistan.The capital city of the restive Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (or the North-West Frontier Province as it used to be known) often finds itself in the front line of the 10-year-old Taliban insurgency and has witnessed appalling bloodshed.

Authorities have beefed-up security in the face of the school carnage, and in response to threats of similar attacks from the Taliban. Checkpoints have been stepped up on roads into the city. Surprise swoops netted 1,200 suspected militants (though many were found innocent and subsequently freed) and more personnel have been assigned to guard the airport. Police have also created a One-Clink SOS app that lets a user alert the nearest 10 police stations in the event of a terrorist attack by touching a smartphone screen. But nobody feels reassured.

Peshawar mother Zubida Saleem said she would rather her children were illiterate than killed in their classroom. She has also changed their school.

“After hearing the rumors that terrorists were threatening all private schools, I stopped sending my children to a private school,” she said. “I am not at all satisfied with what the security forces do these days to eliminate terrorism from Pakistan.”

Saman, a Year 9 student at a private school in Peshawar, said that she is terrified by the thought of going to school. “It’s as if what happened on Dec. 16 happened at my school,” she tells TIME. “It could be my own friends and teachers being killed.”

Fear is also palpable at tertiary institutions. Professor Nasreen Ghufran, chair of the International Relations (IR) department at the University of Peshawar, tells TIME of the “mental stress, depression, anxiety and panic” that have set in, and of lax security.

“The security guards will do a body search of ordinary people but not of officials, which is an open violation of security rules,” she says. “My students are asking me if we can manage the security of our department by ourselves since the government has failed to give us security.”

For many, the only hope of living a life without fear lies in leaving the country. Nawaz Khan’s two sons were in the school attack. The younger son was killed, the elder was seriously wounded.

“My injured son is hospitalized and according to doctors his healing will take almost six months. He won’t be able to take his Year 9 exams. I am so stressed and worried,” he said, explaining that his family was not safe in Pakistan and that he wanted to emigrate. He appealed to the international community to provide asylum to his family.

Award-winning Rahimullah Yusufzai, who was born in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and considered an authority on its affairs, says more school attacks can be expected because educational institutions are far more vulnerable than police or military targets.

He added that “Though the armed forces have cleared various areas of North Waziristan Agency of militants, the Taliban’s top leadership is still secure and able to plan such terror attacks. The military has not conducted ground assaults in the Datta Khel and Shawal areas of the agency, where militants exercise their power freely.”

Yusufzai says that while in past some people were in favor of peace talks with Taliban, the school massacre has changed everything.

“The situation in the city is alarming and parents fear for their children,” he says. “The militants’ attack on the school shows that in the future the Taliban may attack other educational institutions, or markets, bus stands and public places because these are easy targets for them.”

Crackdown in Pakistan: Is it a mock show?

Ziauddin Choudhury

PAKISTAN authorities seem to have decided that enough is enough, and it is time to weed out the extremists that have been running a reign of terror so long in its North West corner. The government and its powerful army have drawn a twenty-point programme to stop the cancer of extremism and religious militancy that in last ten years claimed more than fifty thousand people, the last being the most senseless and mindless killing of one hundred fifty children. The steps include creating a para-military force to combat the extremists, capital punishment of persons charged with extremist violence, and monitoring and regulating funding sources of the religious institutions. We can only hope that this resolve of Pakistan is for real, and it will not go the way of past such resolves of Pakistan authorities that were more known for the rhetoric than for real action.

One wishes that this will to eradicate the evil that has spawned over the last two decades had descended on Pakistan years ago. This would have saved the country thousands of lives, endless amount of financial resources, and above all the image as an intolerant and bigoted society. Unfortunately, it was not to be so; because the powers that are today declaring war on the militants are the same who had once nurtured them and helped grow the monsters they are today.

Birth of the religious extremists or the jihadists (as they call themselves) in Pakistan is no accident. This was by design, with direct help of the powers that be in Pakistan, in particular the army that had always been the king maker of the country. The midwife of religious extremism was General Ziaul Huq, the army general who commandeered his way to presidency and later became the rallying point of the West to wage war against Soviet aggression in Afghanistan. He adroitly used the Western powers' reliance on him to wage this war with locally recruited guerilla forces, motivating them with Islamic zeal to fight a communist regime. With abundant resources showered on him by the West, Ziaul Huq, himself a firebrand Islamist, created seminaries all over the country that would turn out to be recruitment centres of religious militants who would initially fight the soviets as Mujahids (freedom fighters) but later form the seed for the Taliban forces. The Talibans of Afghanistan were the brain child of Pakistan's formidable army intelligence, who ironically would later also have a fraternity in Pakistan imbued with similar ideals.

Taliban-Pakistan army axis would have gone on merrily had it not been for the tragedy of September 11 that exposed the Taliban's shelter to the main perpetrators of the tragedy. Pakistan authorities had to renounce their liaison with the Taliban under duress and helped support US war in Afghanistan to topple them. But in the change of guards, the Taliban simply blended and scattered all over, including slipping into Pakistan where they joined hands with their fellow sympathisers and blood brothers. Although this happened primarily in the territory adjoining Afghanistan, their ideological supporters were spread out all over Pakistan. And these supporters would also be within the army and its powerful intelligence branch.

Two powerful examples of such support were the firebrand imam of Islamabad Lal Masjid, Abdul Aziz, and the leader of Pakistan Taliban Fazlullah. Abdul Aziz, who was a protégé of General Ziaul Huq, preached his bigoted religious philosophy and intolerance day after day for decades, vowing to establish his brand of religious ideals in the country defying the government. He trained his students inside the mosque in handling small arms, and at one stage turned the mosque into a fort when police tried to stop the militant students from attacking them. The mosque would later turn into a battle ground, leading to the deaths of many civilians. The fortress of extremist militants that grew under the nose of Pakistan's powerful military intelligence was broken for the time being, but its main leader Abdul Aziz continued to roam free later and preach his violent philosophy.

Fazlullah, a self-declared leader of Pakistani Taliban, similarly grew his forces under the very eyes of Pakistani authorities. With the support of more than 4,500 militants, by late October 2007 Fazlullah had established a “parallel government” in 59 villages in Swat Valley by starting Islamic courts to enforce sharia. For nearly a year he ruled without any nudge from the central authorities. The Pakistan authorities acted only after goading from the US and Fazlullah had fled the area. But he continued his recruitment mission of diehard suicide bombers who would wreak havoc in various parts of Pakistan. The latest carnage in Peshawar that took lives of 150 innocent school children was also reportedly masterminded by him.

There are many other such militant leaders who are heading one or the other faction of Pakistan Taliban, including Baitullah Meshud, the self-declared ruler of South Waziristan (reportedly killed recently by US drone attack), Samiul Huq (spiritual guide of Meshud), Sheikh Haqqani (Deputy Leader of Tehrik-e-Taliban), etc., who continue to operate in Pakistan. They have been able to operate and guide their forces under the nose of Pakistan authorities either because the authorities have never shown any seriousness to apprehend them or they connive at their presence. This is also largely because the king makers of Pakistan who created the Frankenstein of religious zealots to start with used them as pawns in the past to change power play in Pakistan suiting their objectives. That is why, even though the so-called war against terrorism began in Pakistan more than a decade ago, it never succeeded in weeding out the extremists from the soil of the country.

There may be a lot skepticism about this latest phase of war against religious extremism in Pakistan, but one thing is certain; a second failure will not only pave the way for greater uncertainty about stability of Pakistan, but also peace in the sub-continent. What is spawned in Pakistan can affect and will affect the rest of the region. It is in the interest of us all in the region that this time Pakistan means serious business and the country's establishment, including the powerful military, bring this evil to an end.

How to root out the poison of extremism in Pakistan

BY RAMESH THAKUR

The slaughter of 132 schoolchildren and nine adults in an army school in Peshawar on Dec. 16 by the Pakistan Taliban marked a new low in terrorist depravity. The massacre of the innocents brings to a head several pathologies that need addressing and to that end could prove a catharsis for Pakistan.

The intertwining of religious terrorism, colonization of the state by the army, and obsession with India as the existential threat has mutated into a virulent toxin feeding parasitically on Pakistan. The shock and horror must be channeled into a determination to do whatever it takes to root out the poison.

An Indian, even an expatriate Indian, writing on Pakistan is always a tricky issue. Only Pakistanis can change their national narrative.

The dominant narrative is that India is Pakistan’s mortal enemy which is kept in check by a powerful army and lately by nuclear weapons.

Jihadists have been nurtured as strategic assets in an asymmetric war with the bigger neighbor. The Peshawar massacre proves that the existential threat is from jihadism, not India. The latter can help to contain and then defeat the former, not the other way round.

If it is to purge the toxic Quran-Kalashnikov culture and escape the seemingly inexorable descent into the nightmare of a jihadi state, Pakistan must confront three demons: the false distinction between good and bad jihadists; the excessive influence of the military; and the obsession with India as the enemy.

The last will require a matching change of mindset in New Delhi.

Pakistan produces more religiously motivated terrorism than can safely be exported. Its primary validating argument was negative: The Muslims of the subcontinent cannot be ruled by a Hindu-majority government.

By contrast, an anti-Muslim, anti-Pakistan posture is irrelevant to India’s core identity. The only other glue that could bind the new country was Islam. Pakistan is the only country to name its capital after a religion.

Starting with the dictator General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan’s military has harnessed religious hatred to its strategic goals against Afghanistan and India. But as Secretary of State Hillary Clinton famously said in 2011, if you keep snakes in your backyard trained to bite your neighbors, some day their venom will be aimed at you.

Just as, externally, India might prove to be the main salvation rather than the threat, so, domestically, the anti-jihadists might prove to be Pakistan’s saviours, not traitors.

There are cautionary warnings for Hindu zealots in India, too. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has thus far failed to confront obscurantists in his own party. If India is not to follow the same path to the dead-end of religious extremism, Modi must act decisively against them and reaffirm that India has no future other than as a tolerant, multi-religious, secular polity.

The genius of its greatness lies in a central tenet of Hinduism: Sarva dharma sambhava (all dharmas — truths/religions — are equal and in harmony).

To rescue the state, Pakistan’s military must be brought under full civilian control and all intelligence links to the Islamist militants severed.

Historically Pakistan has been triangulated by the three “A’s”: Allah, the army and America. A common saying is that in other countries, the state has an army. In Pakistan, however, the army has a state.

The enmity with India explains the role of the army as an enduring force of Pakistani politics that rules the country even when civilians are in office. The inflated threat from India validates its size, power and influence, dwarfing all other institutions (just as the alleged threat from Muslim Pakistan validates the militant Hindutva agenda).

Pakistan has always thought of itself as India’s equal in every respect. At the heart of this emotional parity lies the ability to match India militarily. This could not have been done without the alliance with the United States to begin with, and then sustained subsequently with a de facto alliance with China.

Pakistan’s record of double dealing, deceit and denial of Pakistan-based attacks in Afghanistan and in India was based on a four degrees of separation — between the government, army, ISI and terrorists — whose plausibility has steadily faded: It was exploited as a convenient alibi to escape accountability.

While the U.S. viewed Pakistan as an ally against international enemies, the alliance was useful to Islamabad principally in an India-specific context.

Control over Afghanistan through the Taliban gave Pakistan strategic depth against India

Pakistan’s army harnessed Islamism against civilian political parties at home, to maintain control over Afghanistan, and against India.

Washington never confronted the core of Pakistani duplicity under General Pervez Musharraf who deposed elected Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in 1999 and controlled both the military and the state until 2008.

During his rule ,the Islamists survived, regrouped, built up their base and launched more frequent raids across the border in Afghanistan, and increasingly deep into the heart of Pakistan itself. Slowly but surely, Pakistan descended into the failed state syndrome.

What kind of Pakistan does India want?

Is it one that is on the brink of state collapse and failure, splintered into multiple centers of power, with large swaths of territory under the control of religious zealots and terrorists?

Or, is it a stable, democratic and economically powerful Pakistan minus the influence of the three “Ms”: the military, militants and mullahs?

Fearing ripple effects on its own turf because of many potential separatist movements, India has often professed to having a vested interest in preserving a united and stable Pakistan. The answer is no longer so straightforward.

For more than a decade, even as Pakistan has teetered on the brink of collapse and disintegration, India has prospered and emerged as a major player in world affairs.

Yet, South and Southwest Asian terrorism are indeed indivisible.

Many reminders of the enduring relevance of the India equation to Pakistan’s actions in Afghanistan have come from U.S. intelligence confirmations of the links of Pakistan’s ISI to the terrorist attacks on Indian targets in Afghanistan.

India, too, has suffered political blowback in the past. India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi stoked the embers of Sikh religious extremism as a tool of domestic politics.

When she tried to put out the fire once it grew into an out of control monster, she was killed by her Sikh bodyguards in bloody vengeance in 1984.

Her son Rajiv was killed in 1991 by Tamil Tiger suicide terrorists who had been nurtured as an instrument of state policy by his government.

The saying that one country’s terrorist is a neighbor’s freedom fighter no longer applies.

South Asian countries must recognize that terrorism is a common menace and combine forces to exterminate the scourge from the region.

Pakistan Needs Curriculum Reform to Fight the Taliban

Madiha Afzal

On December 16, the 145 victims of the Army Public School attack in Peshawar, Pakistan, bore the burden of their nation’s failures and paid for them with their lives. The survivors that day witnessed the unthinkable, and lost their childhoods. I went to school in Pakistan too, but it was a different country, one where children could still be children. Yet the seeds of today’s Pakistan had already been sown by the time I was in elementary school. This was the end of General Zia’s time—a man who ruthlessly Islamized the country beyond recognition, changing laws and curricula, restricting freedoms, and transforming society.

After the horror in Peshawar, we have seen Pakistanis unite, at least for now—against the Taliban (TTP), who took responsibility for the attack in Peshawar, and who have killed tens of thousands of their fellow citizens over the last decade. The country is also united against Taliban apologists, such as the radical cleric Abdul Aziz of Islamabad’s Red Mosque, who refused to condemn the TTP until forced by days of protest to do so. But until Peshawar, Pakistan’s media, its leaders, and ordinary citizens shied away from naming terrorists and terrorist groups, refused to acknowledge their identity, and instead pointed fingers at the U.S. and India for creating havoc in the country. This obfuscation and denial has allowed militants to garner sympathy, to survive, and to operate freely.

For the last year and a half, with support from a U.S. Institute of Peace research grant, I have visited public and private schools following the official curriculum in Pakistan, attending classes and talking with high school students and teachers. I asked students about what they thought was causing terrorism in Pakistan. The majority of them said that “foreign influences”—the United States and India, and sometimes Israel—were responsible. Some of these students gave a straight up conspiracy theory version of this argument, that these countries wanted to destroy Pakistan, and so they trained or funded or even sent terrorists into Pakistan. They said that it was impossible that Muslims could be responsible for killing other Muslims. Others argued that terrorists engaged in attacks in retaliation for Pakistan having helped the U.S. in “America’s war”—in Afghanistan—or that they undertook terrorist attacks in response to U.S. drone strikes and involvement in Pakistan.

A smaller set of students argued that the terrorists want to implement Islam in Pakistan, that the country is on the wrong, un-Islamic path now—thus giving a religion-based justification for militant behavior.

These aren’t madrassa students. I visited public and private schools, the kind that reach a majority of Pakistan’s population. This isn’t down to illiteracy either—these students are in high school. What drives them to think this way? It is easy to blame Pakistan’s media, because it often spouts these same conspiracy theories. But the blame rests with Pakistan’s curriculum, society, and state. And, yes, the media.

For the last 35 years, Pakistan’s official curriculum has been an amalgam of religious dogma, historical half-truths, blatant lies, biases, and conspiracy theories. The official textbooks teach children that Pakistan’s “ideology” is Islam; that its foreign policy is ideological—its guiding principle is friendship with the Muslim world; that various other religions and nations are “evil” and “the enemy”—especially India and the Hindus, but these words are also used for Jewish people and Israel. A number of these textbooks glorify armed jihad, or struggle, against non-Muslims. The textbooks depict major historical events as the results of conspiracies—of Hindus and the British against Muslims in colonial India, rendering Pakistan’s independence necessary; and of the “secret arrangement of big powers” that led to the breaking up of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. The West is described as having “two-faced” characters, and the United States is portrayed as having betrayed Pakistan at key points in its history.

Teaching revolves around rote memorization—line by line, page by page—and the sole purpose of classes is to ensure rote learning for board exams, where the material is expected to be regurgitated verbatim. There is no room for questioning the textbooks, no discussion in class, no mention of good versus bad sources of information, no alternate views presented. It’s all black and white: Muslims and Pakistan are “good” and the rest of the world is not, and they are out to get us. Little wonder, then, that Pakistanis find it tough to believe the Taliban come from among them and are Muslims.

But for the origin of the specific conspiracy theories about the Taliban, we need look no further than elements of the Pakistani state and radical clerics. They function as “conspiracy entrepreneurs”—a paper by Sunstein and Vermeule sets up a useful framework for thinking about this—who use these theories to divert attention from their internal failings and pin blame elsewhere. Pointing the finger at India gives sustenance to Pakistan’s military, whose power depends on the conflict with India.

Pakistanis rely on the opinions of those in positions of authority to form their own—partly because of the country’s hierarchical society and culture, and partly because they are never taught how to seek and evaluate evidence in school—leading to these theories being accepted and then spreading quickly in “informational cascades”.

The outrage sparked by Peshawar has finally seen the government take an aggressive stance against the Taliban, with a force that has been lacking before. Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has announced that military courts will be set up to deal with terrorism cases. There is finally some talk about reclaiming the narrative from Taliban apologists—Pakistan’s interior minister Chaudhry Nisar asked the media not to give airtime to Taliban sympathizers—and the need for madrassa reform. But we have heard nothing about the need for curriculum reform in eliminating the roots of our national sense of denial and sympathy for militants.

That is unsurprising. In part, this is because a decentralization law passed in 2010 saw the federal government delegate curriculum formation to the provinces. In fact, in one province, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, marginal curriculum improvements made over the past few years are currently being reversed under pressure from Islamist parties in the province, and theword jihad is being reintroduced in their textbooks. In part, it’s because the government just doesn’t get the need for such reform. We have an entire generation of policymakers schooled in this system who don’t realize there’s anything wrong with it, and who systematically push back against reform.

But despite the impediments, curriculum reform is urgent. With critical thinking capabilities and a reformed curriculum, when faced with conspiracy entrepreneurs like the terrorist Hafiz Saeed, who has blamed the Peshawar attacks on India, the Pakistani public would be equipped to counter their theories.

So it is time for Pakistan to rewrite its textbooks to give its citizens a real, complete picture of history—no conspiracies attached; to purge religious dogma and hatred toward others; to introduce critical thinking in the curriculum; and to encourage global citizenship. This won’t be easy. Islamic parties will protest, but the government must ignore them. Teachers will need to be reeducated and retrained, and the results will be visible only in the long term. But that is the only way to achieve a Pakistan for the next generation that is even safer than the one where I went to school.

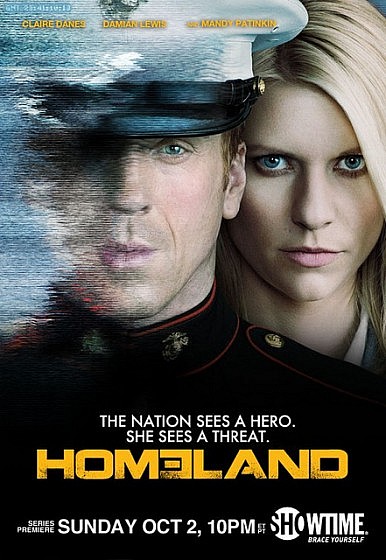

The Hypocrisy of Pakistan's Homeland Criticism

North Korea is not the only country that has taken offense to its portrayal in Western media. Recently, Pakistani officials have criticized the American television series Homeland, which airs on Showtime, for portraying Pakistan in a negative light.

Pakistani officials are upset because the show portrays their country as a “hellhole,” to use their words.Homeland focuses on American intelligence officers and the latest season mostly occurs in Pakistan. The Pakistani embassy in the United States released a statement saying that it was “very unfortunate that the underlying theme of ‘Homeland’ Season 4 is designed to create a negative perception of both the U.S. and Pakistan.” Pakistani officials were especially upset because Homeland showed agents from Pakistan’s intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), assisting local terrorist groups, including helping one attack the U.S. embassy in Pakistan. This has led to a statement from Pakistan that “insinuations that an intelligence agency of Pakistan is complicit in protecting the terrorists at the expense of innocent Pakistani civilians is not only absurd but also an insult to the ultimate sacrifices of the thousands of Pakistani security personnel in the war against terrorism.” Pakistani commentators also argued that the show fuels American paranoia over Pakistan and the Islamic world in general.

These statements from Pakistan ring hollow. Pakistan has a long history of state support of terrorist groups that conduct operations in India, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, even against U.S. interests. While Homeland is obviously a fictitious account, its theme of Pakistani support for militant organizations is not off the mark. Asanalysts have pointed out, Pakistan is unlikely to change its policy of sponsoring militant groups even after the Peshawar school attack. Recent incidents have confirmed this. On New Year’s Eve, the Indian Coast Guardintercepted a Pakistani fishing boat off the coast of the western state of Gujarat. The incident fueled speculation that the boat was transporting people and supplies to carry out another Mumbai-style attack. The Mumbai attack of 2008 featured a small, armed team attacking several key buildings simultaneously.

The truth may never be known for sure since the Pakistani boat blew itself up with some of the explosives contained within the boat. All four individuals on the boat are presumed dead. While smuggling is a possibility, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi stated that the boat was involved in a “possible terror operation.” As a new year begins, it seems as though it is business as usual for Pakistan and its support of terrorist organizations. No negative portrayal in American television or terrorist attack in Peshawar is going to change its overall strategic calculus.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)