M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Thursday, April 9, 2020

کرونا وائرس بڑی ہوشیاری سے انسانی جسم کو دھوکہ دیتا ہے: ریسرچ

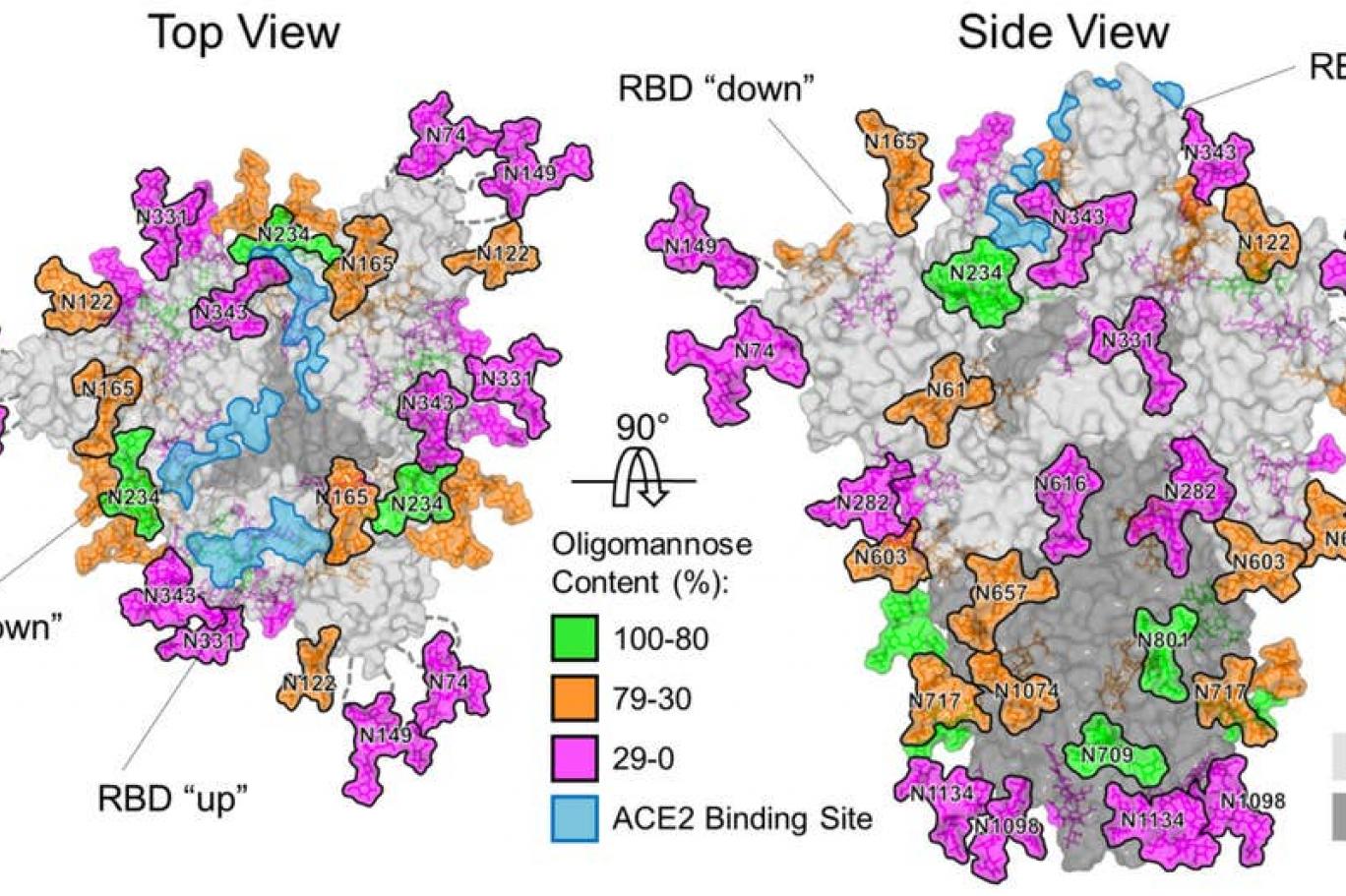

ساؤتھ ہیمپٹن یونیورسٹی کے سائنس دانوں کے مطابق کرونا وائرس ایک ایسا 'بھیڑیا ہے جو بھیڑ کی کھال' پہن کر انسانی جسم میں داخل ہوتا ہے۔

ایک تازہ تحقیق کے مطابق کرونا (کورونا) وائرس بڑی ہوشیاری سے انسانی جسم میں داخل ہوتا ہے۔ یہ خود کو نشاستے سے بنے ایک لبادے میں چھپا کر'بھیڑ کی کھال میں بھیڑیا' بن جاتا ہے۔

یونیورسٹی آف ساؤتھ ہیمپٹن کے سائنس دانوں نے معلوم کیا ہے کہ انسانی خلیوں میں داخل ہوتے وقت کرونا وائرس کا پتہ نہیں چلتا کیونکہ اس کے اردگرد نشاستے کا ایک غلاف ہوتا ہے جسے 'گلائیکین' (glycans) کہتے ہیں۔

تاہم کرونا کے گرد موجود غلاف دوسرے وائرسوں، جیسے کہ ایچ آئی وی کے مقابلے میں کمزور ہوتا ہے۔ تحقیق کرنے والی ٹیم کو امید ہے کہ وائرس کے کمزور غلاف کی بدولت ویکسین کی تیاری کے لیے کوششوں میں اہم اور حوصلہ افزا معلومات ملیں گی۔

تحقیقی ٹیم کے سربراہ پروفسر میکس کرسپِن نے وضاحت کی ہے کہ کرونا وائرس انسانی خلیوں میں داخل ہونے سے پہلے خود کو ان کے ساتھ چمٹانے کے لیے ایسے کانٹے استعمال کرتا ہے جوگلائیکین میں لپٹے ہوئے ہیں۔ یہ گلائیکین وائرس کی پروٹین کو انسانی جسم کے مدافعتی نظام سے چھپانے کے قابل بناتے ہیں۔

ڈاکٹر کرسپِن نے کہا: 'خود کو نشاستے میں چھپا کر وائرس بھیڑ کی کھال میں بھیڑیا بن جاتا ہے، لیکن ہماری تحقیق کی ایک اہم بات یہ ہے کہ چاہے نشاستے کے جتنے بھی غلاف ہوں، اس کرونا وائرس کے گرد اتنی مضبوط حفاظتی تہہ نہیں ہے جتنی دوسرے وائرسوں میں ہوتی ہے۔'

انہوں نے مزید کہا کہ ایچ آئی وی جیسے وائرس گلائیکین کی حقیقی موٹی تہہ میں لپٹے ہوتے ہیں جب کہ کرونا کے گرد موجود غلاف پتلا ہے۔

پروفیسر کرسپِن نے کہا ہو سکتا ہے کہ ایسا اس وجہ سے ہو کہ یہ 'مارو اور بھاگو' (hit and run) وائرس ہو, یعنیٰ یہ تیزی سے ایک سے دوسرے شخص کو منتقل ہوتا ہے۔ گلائیکین کی پتلی تہہ کے نتیجے میں مدافعتی نظام کو وائرس پر قابو پانے کے لیے کم رکاوٹیں پار کرنی پڑتی ہیں۔

یہ ویکسین کی تیاری کی کوشش کرنے والے محققین کے لیے ایک اچھی خبر ہے۔ یونیورسٹی ساؤتھ ہیمپٹن کی تحقیق میں جو آلات استعمال کیے گئے، ان کے لیے اس سے پہلے بل اینڈ میلینڈا گیٹس فاؤنڈیشن نے ایڈز کی ویکسین کی تلاش میں مصروف عالمی اتحاد کے توسط سے گرانٹ دی تھی۔

کورونا وائرس سے مقابلے کیلئے پلان ہونا چاہیے، بلاول بھٹو

چیئرمین پیپلز پارٹی بلاول بھٹو زرداری کی سربراہی میں وڈیو لنک کے ذریعے ایک اجلاس منعقد ہوا، جس میں کوروناوائرس کے حوالے سے حکومتی حکمت عملی زیر بحث آئی۔

اس موقع پر بلاول بھٹو زرداری کو سندھ حکومت کی جانب سے بریفنگ دی گئی۔ اور بتایا گیا کہ بدین میں آئسولیشن سینٹر بنایا گیا ہے، ریسرچ ٹیم صورت حال کو سامنے رکھ کر مستقبل کے حوالے سے تحقیق کررہی ہے، نجی اسپتال طبی آلات و عملے کے ساتھ حکومت کی مدد کررہی ہے۔

بلاول بھٹو زرداری نے کہا کہ بدترین حالات میں کورونا وائرس سے مقابلہ کرنے کے لیے پلان ہونا چاہئے، گنجائش اور صلاحیت میں اضافے کے حوالے سے تیاریوں میں تیزی لائی جائے۔

بلاول بھٹو نے کہا کہ سندھ حکومت اپنی ریسرچ میں ملک بھر میں کورونا کی موجودہ صورت حال کاجائزہ لے، کوئی بھی صوبائی حکومت اکیلے کچھ نہیں کرسکتی، وفاق کو مدد کرنا ہوگی، وفاق سے بار بار مطالبہ کررہے ہیں وہ سندھ کی مدد کرکے اپنی ذمے داری ادا کرے۔

انہوں نے کہا کہ ہم سب کو مل کر کورونا وائرس کی وباء کا مقابلہ کرنا ہوگا، بلاول بھٹو نے ہدایت کی کہ سندھ حکومت سنگین صورت حال کے لیے تیار رہے۔

اجلاس میں وزیراعلیٰ سندھ مراد علی شاہ اور وزیرصحت عذرا پیچوہو، سیکریٹری صحت کے علاوہ ڈاکٹر باری، ایم بی دھاریجو اور ریحان بلوچ بھی شریک ہوئے۔

Pakistani doctors need PPE to fight Covid-19, PM Imran Khan puts paper tigers on the job

NAILA INAYAT

Perhaps Pakistan’s more serious bodies dealing with the coronavirus crisis weren't up to the task. It seems the Corona Relief Tiger Force was just what the doctor prescribed.

Pakistan has what the rest of the world doesn’t. But don’t think too much: it’s not something that Pakistan actually has. The Imran Khan government is merely using them to sell itself as a caretaker in these uncertain times. They are tigers — extinct in real life, but living in Pakistan’s imagination.

The government has instituted a Corona Relief Tiger Force, which currently has more than 8,00,000 ‘registered members’. Whether they are real or paper tigers, we would have to wait and see. But these volunteers comprise students, social workers, doctors, teachers, lawyers, journalists and even retired armed forces personnel, according to official details.

Perhaps Pakistan’s more serious bodies dealing with the coronavirus crisis in the country — such as National Security Committee, National Coordination Committee, National Command and Operation Centre — weren’t up to the task. It seems the Corona Relief Tiger Force was just what the doctor prescribed.

PM’s love for tigers

The soon-to-be-activated force was first announced by Prime Minister Imran Khan last month in his two ‘F’s strategy to fight the coronavirus: Fund for corona and Force of tigers. Funding from overseas Pakistanis has been the cornerstone of Imran Khan’s strategy to solve any problem in his philanthropic or political life. Tigers are mandated to first identify needy people — they’ll find out who is unemployed, then go door-to-door and give out ration, and spread awareness regarding safety measures.

Fighting coronavirus with paper tigers

Fast forward to 2020 and Imran Khan is now recruiting Tigers to do jihad against the coronavirus. However, neither are the Tigers benign anymore nor is the pandemic, which they are up against.

Divisive in nature, the relief force tends to give a clear signal: if you are a Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) supporter, you are welcome to become a Tiger and don an alleged t-shirt in party flag colours of green, red and white. But who will dare break it to Imran Khan that he is now the PM of Pakistan and not of Shuakat Khanum or Tehreek-e-Insaf?

And if you thought the Imran Khan government was capable of using the funds from the relief force for something good, think again: there are fears that the money will be spent on manufacturing t-shirts for the volunteers, fears that the government denies. People on social media have rightly called the recruitment, training and deployment of Tigers a waste of money, which could have been instead used to buy protective gears for the doctors.

Doctors and paramedic staff across Pakistan have been demanding personal protective equipment (PPE) and other facilities to help treat the patients. But what did the Imran Khan government do? In Quetta, Balochistan, doctors demanding protective gears were baton-charged and more than 50 of them were later arrested. Elsewhere, doctors protesting by wearing garbage or plastic shopping bags to highlight the lack of gloves and masks have been issued show cause notices.

When countries around the world are focusing on strengthening the healthcare system and helping their doctors — the first line of defence against the coronavirus — Pakistan is empowering paper Tigers. It is by floating political ideas such as these that the PTI government makes people accuse it of not being serious — that is, when they aren’t pointing out its ill-preparedness to deal with the pandemic.

Putting young in danger

The work that the government plans to get done through the Corona Relief Tiger Force is something that grassroots local bodies are equipped to do. There are several governmental, non-governmental and religious organisations with millions of volunteers distributing rations, which the PTI thinks its Tigers should do.

To justify it by saying that Pakistan has a large population of young people who would want to help with the fight against coronavirus or by that they did enormous relief work during floods and earthquakes and so they can do it in this case too is beyond stupid. For one, the nature of the pandemic is different from a natural disaster. Young people without proper training and protection will be at risk of getting infected, and the number of positive Covid-19 cases will keep rising. But does this government even think?

Is it a good idea for the PTI government to get sidetracked like this in the middle of a pandemic? The answer is clear. PM Imran Khan sees coronavirus as an opportunity for his party members, whom he has been telling that by engaging in acts of charity and welfare — they just have to put up a show — they can have an edge over their political opponents. The members, in return, must be expecting a personalised Tiger badge if they do well during coronavirus.

Pakistan’s Hazaras to India’s Muslims – people are finding Covid-19 scapegoats

SRIJAN SHUKLA

Since the Black Death plague in the 14th century, when people went after Jews, beggars, and foreigners across Europe, every disease outbreak has been followed by racism and xenophobia.

Atragedy is a terrible thing to waste – for the haters.

Since the Black Death plague in the 14th century, every outbreak of an infectious disease has also been closely followed by an outbreak of stigma, racism and xenophobia. Things haven’t changed much 600 years later. As the world grapples with Covid-19 pandemic today, some countries are also finding their favourite scapegoats to hate on.

During the Black Death, people went after Jews, beggars, and foreigners across Europe. This time around, the Iranian government is blaming Jews, and the Israelis in turn are blaming Palestinians. The Chinese are blaming Uyghurs and Pakistanis are blaming the Hazaras. And at home, people en masse are blaming Muslims over the Tablighi Jamaat congregation in New Delhi.

In a world marked by hyperglobalism and nationalist populism, we all are living in societies with almost state-sanctioned hatred against persecuted groups and minority communities. In such a world, the coronavirus pandemic is causing societies to find their own personal scapegoat to blame.

These new patterns of hatred during coronavirus pandemic reflect the already existing structures of marginalisation and persecution. Only now it’s on a global scale.

Global disease, local hatred

It all began with US President Donald Trump. Given that the novel coronavirus originated in Wuhan in China, the not-so-civil leader used this opportunity to label Covid-19 as the “Chinese virus”. This follows the US-China trade war and all the rhetoric that accompanied it in the last two years. This also heightened instances of racism and discrimination faced by the Asian population in the US.

While Trump’s politics was expected, it makes little sense that the deeply persecuted Hazaras and seething African asylum seekers in Italy would be made the scapegoat in Pakistan and Italy.

“We are troubled that government officials in Balochistan are scapegoating the already vulnerable and marginalized Hazara Shi’a community for this public health crisis,” said United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) Commissioner Arunima Bhargava.

The African asylum seekers – the continent with the least Covid-19 incidence – were blamed by former Italian deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini as the main cause of the virus’ spread in his country. When a boat carrying 276 Africans rescued in the Mediterranean, was allowed to dock in Sicily, Salvini went on a limb and asked Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte to resign, accusing him of his inability to defend “Italy and Italians”.

In China, where the authorities, unlike anywhere else in the world, are actually acquainted with where the virus originated and how it spread, are using the crisis to further persecute the Uyghur community. They are forcing them to donate organs in order to save the lives of the infected Han population.

In India, while the Tablighi Jamaat need to be held accountable, the Muslim population at large has had to face the brunt of a government action and media-run hate campaign that blamed them for single-handedly spreading the virus across the country. And as shown by journalist Shoaib Daniyal of Scroll, the very premise of these “statistical” claims were based on basic sampling bias and errors.

“The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has uncovered social and political fractures within communities, with racialised and discriminatory responses to fear, disproportionately affecting marginalised groups,” notes a new study in The Lancet.

Hyper-globalisation meets nationalism

The three major economic crises of the recent past – Asian financial crisis, global financial crisis, and now the coronavirus pandemic – have all been caused by unrestricted global flows. In the first two instances, it was flows of global capital; and in the third, it was unrestricted human flows.

The inability of nation-states to balance between these flows with the task of providing welfare to their citizenry gave rise to populist nationalism around the world. The sheer lack of experience ensures that when met with a crisis, these populist nationalist leaders resort to the only thing they are really good at — manipulating the masses and raking up the politics of fear and discrimination.

The Scary State of Pakistan's Many Nuclear Weapons

By Caleb Larson

Bad security and a lack of cash for upgrades are among the many problems.

Unlike India, Pakistan lacks a sea-based nuclear delivery platform and thus does not have a three-pronged nuclear triad. Worst still for Islamabad, Pakistan is hindered by a lack of cash, and there are questions about how secure the nuclear missiles in Pakistan are from falling into non-state actor’s hands.

First-Use Deterrence

Unlike India, Pakistan does not adhere to a no-first-use nuclear policy. That is to say, Pakistan reserves the right to use nuclear weapons first, rather than in retaliation after being struck first. India is Pakistan’s main geostrategic enemy, and their nuclear arsenal exists only to deter India. A Pakistani military officer, General Khalid Kidwai, mentioned in 2002 what Pakistan’s nuclear use strategy could look like, saying that Pakistan would willingly launch nuclear missiles if the existence of the state was at risk. He outlined the following points that would merit a nuclear response from Pakistan:

India attacks Pakistan and conquers a large part of its territory;

India destroys a large part of either Pakistan’s land or air forces;

India attempts the economic strangulation of Pakistan;

India pushes Pakistan into political destabilization or creates large-scale internal subversion in Pakistan.

So while not completely ambiguous, there is also an element of strategic ambiguity in Pakistan’s policy.

Hindered by Cash

When compared to their neighbor India, Pakistan plays second fiddle. India is “more powerful than Pakistan by almost every metric of military , economic, and political power—and the gap continues to grow,” according to some experts.

This is reflected in Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal, which unlike the India triad of land, air, and sea-based delivery, can only deliver payload from land, via ballistic missiles, or from the air, via jet bombers.

Like India, Pakistan has also received a large amount of assistance from abroad in developing their land-based nuclear missile program. The majority of this assistance has come from the enemy of their enemy: China. Pakistan has also reportedly received assistance from both North Korea and Iran.

In contrast to India, the majority of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is made up of “short and medium-range ballistic missiles,” though it has made significant progress in “developing cruise missiles.”

Non-state Threats

One of the concerns regarding Pakistan’s arsenal is not how destructive it could be, but rather how insecure it may be. An on-again, off-again Taliban insurgency in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border regions, as well as home-grown militant groups have raised alarm bells in Washington previously. Part of the worry is that the United States does not know for certain the exact location of all of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons.

Speaking to the New York Times, some American officials expressed their concern about “new vulnerabilities for Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal, including the potential for militants to snatch a weapon in transport or to insert sympathizers into laboratories or fuel-production facilities.”

Because of these concerns, the Obama administration had continued a Bush-era program reportedly worth $100 million to aid Pakistan in securing the physical protection surrounding its nuclear arsenal, and to help train up the security services that guard Pakistan’s nuclear facilities.

In the end…

…it may matter little that Pakistan’s nuclear capabilities are significantly less capable than those of their geostrategic rival, India. Still, better not to take any chances.

https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/scary-state-pakistans-many-nuclear-weapons-142277

Pakistan’s Fragile Health System Faces a Viral Catastrophe

By FaseehMangi

The country of 210 million is ill-prepared for the pandemic.Syed Mohammad Yahya Jafri, 22, a Pakistani student from Karachi, was coming to the end of a two-week pilgrimage to Iran when his head started spinning. He felt weak and feverish but decided the best thing to do was head home. It was mid-February, and most countries weren’t yet blocking people with flu-like symptoms from traveling.

No one stopped Jafri at the airport in Tehran when he arrived for his Iran Air flight, or on landing in Karachi. He went about his routine there, encouraged that his symptoms seemed to be intermittent. But when they became constant, along with a nagging cough, Jafri went to a local hospital and insisted on being tested for the novel coronavirus. He soon learned he was one of the first two confirmed cases in Pakistan.

A little more than a month later, the country has about 4,000 official cases—likely a fraction of the true figure—and is preparing for an outbreak that could drive its fragile health-care system to the breaking point. Pakistan’s health expenditures, according to the World Health Organization, are just 2.9% of gross domestic product, significantly below neighboring India and less than half the global average. The country is one of only three with ongoing polio transmission, and it’s struggled in recent years to contain AIDS and dengue outbreaks.

Health care in Pakistan “continues to suffer from coordination challenges and an acute shortage of resources,” says Arsalan Ali Faheem, a consultant at DAI, a Bethesda, Md.-based company that advises on development and health projects. “The country has been hard-pressed to find resources for health delivery.”

Pakistan’s biggest problem is money. Health care competes for scarce funds with the armed forces, which absorb a huge share of the national budget. Ambulances are funded largely by charities, and even when hospitals do have critical-care equipment, they may lack staff trained to operate it. Prime Minister Imran Khan has tried to improve services, but the government has limited influence over the provincial authorities that deliver much of the care. Together, federal and provincial health spending in the last fiscal year was the lowest since 2016, according to Asad Sayeed, an economist at the Collective for Social Science Research in Karachi.

“The camp was a breeding ground for the virus” Proximity to one of the first hot spots outside East Asia has been an important factor in the local outbreak. Shia Muslims such as Jafri represent a bit more than 10% of the Pakistani population, and thousands travel every year to holy sites in neighboring Iran. Until mid-March, when Pakistan closed its land borders, most were able to return home without disruption. At one border crossing, thousands of travelers without symptoms were waved through. Those who felt ill were sequestered in a makeshift tent city on the Pakistani side that, according to patients, had no soap or hand sanitizer. “If one is affected, everyone would get it,” says Mohammad Hussain, 42, who spent more than two weeks there. “The camp was a breeding ground for the virus.”

Khan’s administration is playing catch-up. Public gatherings have been banned and travel sharply curtailed, though the government struggled to reach a deal with religious authorities to close most mosques and shrink crowds at Friday prayers. Bolstered by the military, officials are going door to door looking for possible cases, a daunting task in one of the world’s most populous countries. In Karachi, local authorities have converted a convention hall into a 1,200-bed field hospital in anticipation of a surge in patients.

The number of tests for Covid-19 performed in Pakistan is less than 50,000

So far, Khan has ruled out a nationwide lockdown like that in India, arguing that suspending economic activity in a country where a quarter of citizens live in poverty would be a humanitarian disaster. Provincial governments in Punjab and Sindh, which contain about three-quarters of the national population, have tried to close workplaces and keep people at home, but compliance has been spotty, with residents still crowding snack carts and supermarkets.

Pakistan’s other obstacles would be familiar to doctors elsewhere. Diagnostics are in short supply: Fewer than 50,000 tests have been performed, compared with about 2 million in the U.S. The Aga Khan University Hospital, one of Karachi’s top medical facilities, closed its doors to new coronavirus patients in late March after crowds overwhelmed a screening clinic, potentially exposing staff to infection. Protective gear for physicians is a problem. One of the first Pakistanis to die from Covid-19 was a 26-year-old doctor.

With such limited resources, keeping the disease under control will fall largely to regular citizens. Jafri, now recovered, says he’s fearful that message isn’t getting through. After a slow start, “the government is doing all it can,” he says. “The biggest problem are the people who are not taking the virus seriously.”

BOTTOM LINE - With underfunded hospitals and disjointed management, the coronavirus could push Pakistan’s health-care system to collapse.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-08/pakistan-s-fragile-health-system-faces-a-viral-catastrophe

#Pakistan - The #coronavirus outbreak may hurt Imran Khan's political future

By Tom Hussain

There are increasing signs of disagreement between Prime Minister Imran Khan and the establishment in Pakistan.

Populous Pakistan has not yet made the grim headlines spawned by the global coronavirus pandemic, despite reporting its first infections on February 26.

Sadly, in the weeks to come, it will. The number of infections is projected to spiral into the millions. And as the death toll mounts, the blame for the government's failure to learn from the mass outbreaks in neighbouring China and Iran will fall squarely on the government and Prime Minister Imran Khan, whose reluctance to act decisively may cost him dearly.

Initially, its response to the brewing crisis was lackadaisical. Responding to criticism in his first televised speech on March 17, Khan said his government had been monitoring the pandemic since January, but did not begin emergency consultations until the first cluster of infections was identified on March 12.

Notably, this discovery by the opposition-controlled Sindh provincial government exposed the failure of the federal authorities to properly screen and quarantine thousands of pilgrims returning from Iran.

Had Sindh's Chief Minister Murad Ali Shah not taken the initiative to start testing returnees upon learning of the first infections in the provincial capital Karachi, the metropolis of 18 million souls would have become another Wuhan, and health authorities in other provinces would not have been alerted to the infectiousness of the pilgrims.

However, when Khan addressed the subject, he was absurdly fatalistic. The spread of the coronavirus was inevitable, he said, but there was no need to panic because for the majority, the disease would feel like mild flu. He ruled out a nationwide shutdown to contain the virus, saying Pakistan's poor were dependent on daily incomes and would starve.

This deprived the country of a clear sense of direction. The federal government and provincial authorities - even those ruled by Khan's PTI party - each reacted differently. Sindh moved steadily towards a shutdown, while others enacted piecemeal measures like school closures and shortened shopping hours. There was no nationwide effort to urgently equip hospitals and front-line healthcare providers. There was not even a clear, mass messaging campaign launched by the authorities.

Pakistan's powerful military was left with no option but to make its presence publicly felt. On March 23, Pakistan's national day, chief spokesman Major General Babar Iftikhar announced troops would be deployed across the country in response to calls for assistance from the provincial authorities.

This was a clear signal that the establishment was losing patience with Khan's refusal to provide responsible leadership when the country most needed it. At a press conference on March 24, several TV anchors humiliated the prime minister.

Instead of accepting the counsel of the military, which helped usher his government into power in August 2018, Khan responded to criticism with obstinacy.

Addressing a video conference of parliamentary party leaders called by the opposition on March 25, Khan opposed moves by the Sindh government to enforce a province-wide shutdown, thereby stymying any matching measures in the other provinces, where his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party and their allies hold power.

The resultant leadership vacuum was exploited by populist clerics, whose refusal to cancel congregational prayers last Friday and other religious gatherings planted viral time bombs which began to detonate across the country, setting Pakistan on the path to a massive outbreak.

Again, Khan took to the airwaves on March 31, amid expectations that he would finally grab the bull by the horns. Instead, the prime minister insisted that Pakistan's youthful demographic would save it from the fate of other infected countries, and questioned the effectiveness of a lockdown.

The military had had enough. Another video conference of federal and provincial leaders was held on April 1 with army chief of staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa attending in combat fatigues, rather than usual dress uniform. In the official video of the event, he silently frowned at the federal cabinet.

Afterwards, Planning Minister Asad Umar, rather than Khan, announced that the varying restrictions on public movement introduced by the federal and provincial authorities in the second half of March would be extended until April 14, and the military announced that Lieutenant General Hamood Khan will be in charge of its command and control apparatus would oversee the state's response to the pandemic.

The ramifications of the all-powerful military's intervention could be dire for Khan's administration, once Pakistan has overcome the pandemic. Tired of the government's poor governance, in particular its mishandling of the economy, the military reportedly reached out to opposition party leaders last autumn. An increasingly public conversation among opposition politicians on how to go about removing Khan has ensued, fuelled by the subsequent release from jail of ailing former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on medical grounds.

Since then, the Pakistani news media has been rife with speculation about the longevity of Khan's administration. Until the coronavirus spread from Iran, eminent analysts generally felt that Bajwa was prepared to give Khan time to improve his government's performance.

That view has shifted markedly since the military was forced by Khan's ineptitude to take control of Pakistan's emergency response to the pandemic. Veteran Urdu language columnist Suhail Warraich, one of a handful of analysts renowned for accurately predicting the demise of governments, on Monday wrote that Khan has until June to get his administration's act together and mend fences with the opposition, failing which, violent political change may follow.

That "message" should be viewed as a warning that the military is in no mood to shoulder the blame for Khan's shortcomings. With Pakistan's very future at stake, the trajectory of the pandemic and his political career may well prove inseparable.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)