M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Monday, December 10, 2018

#Pakistan - 13 years on, 500 schools in hilly areas await reconstruction

Mohammad Ashfaq

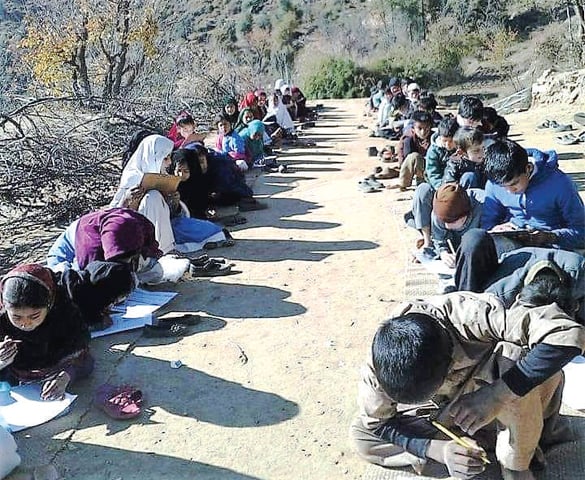

Thousands of students enrolled in around 500 shelter-less government primary schools in the hilly areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have been braving the shivering winter seasons since their schools had been demolished in the 2005 devastating earthquake.

The federal and provincial governments have failed to provide a conducive learning environment to the students at the shelter-less schools and the same number of schools functioning in rented buildings in Hazara division.

The devastating earthquake had destroyed thousands of schools and other government departments. Since 2005, a large number of schools have been either functioning in rented building or in the tents, however, the students of 500 schools still attend classes under the open sky.

CM’s adviser says rebuilding of quake-hit schools responsibility of Erra

According to the annual statistical report of government schools, Kohistan stands on the top of the list by having 162 shelter-less schools including 17 for girls; followed by Mansehra with 151 schools including 43 for girls.

The report prepared by the elementary and secondary education department states that there are 51 shelter-less schools in Battagram, of them eight for girls; 42 in Abbottabad including 11 for girls; 27 in Shangla; 24 in Torghar including seven for girls and three in Swat.

The students of the government primary school Hanjoo in Peshora union council of Thakot area in Abbottabad also get education under the open sky.

“Currently over 100 students are enrolled in government primary school Hanjoo but the school has no building,” said Javed Iqbal, the general secretary of All Primary Teachers Association Battagram.

He told Dawn that students of six classes from nursery to 5th grade gathered in a room of mud provided by the community during snowfall or rain. Asked as to how the students of six different grades were taught in a single room, he said that it was not possible but the teachers made efforts to keep the students engaged in such situation by teaching a common topic rather than the textbooks.

“For instance, we teach them prayers or general knowledge when the students of different grades are setting in a single room,” said the teacher.

Another teacher from Mansehra said that there was no concept of schooling during bad weather conditions. “The shelter-less schools remain closed until rain or snowfall is stopped,” he said.

The teacher said that in summer season, the students were forced to sit under the shadow of trees.

“Neither teachers can teach with concentration, nor students can learn because it is not possible when non-academic activities take place in the surroundings,” he said.

A senior official in the Kohistan district education office told Dawn that out of 145 shelter-less schools, many were functioning in a single room guest house provided by the community members.

Ziaullah Bangash, adviser to chief minister on elementary and secondary education, when contacted, said that it was the responsibility of the Earthquake Reconstruction Rehabilitation Authority (Erra) to reconstruct the destroyed schools. After the 2005 earthquake, the federal government had established Erra for rehabilitation and reconstruction of the destroyed infrastructure.

“We are in consultation with Erra regarding the reconstruction of the destroyed schools,” said Mr Bangash. He said that the previous PTI-led provincial government had also taken up the issue with Erra to fulfil its responsibilities by reconstructing the schools.

He said that more meetings with Erra were also in the schedule of the education department in that connection.

“If Erra refuses, then we will approach international donor organisations for reconstruction of schools in the hilly areas of the province,” he added.

How the India-Pakistan Conflict Leaves Great Powers Powerless

The U.S. helped prevent war in 2008. Those days are gone.

A decade ago, the world watched in disbelief as terrorists from the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba group ripped through the Indian financial capital of Mumbai. By the time the 10 attackers were stopped four days after the assault began, they had killed 164 people—Americans and other foreign nationals among them—and left over 300 injured. India’s 9/11, as the Indian media dubbed it, had unfolded. India, having long seen the Lashkar-e-Taiba as a direct proxy of the Pakistani intelligence outfit, the Inter-Services Intelligence, blamed the Pakistani state for having directed the attack. A near-war crisis between the two nuclear neighbors ensued in its wake, offering a stark reminder why U.S. President Bill Clinton termed this part of the world “the most dangerous place” on Earth at the turn of the century.

Ten years after the Mumbai attacks on November 26, 2008, the Indian-Pakistani rivalry remains as entrenched as ever. While the two countries have avoided major wars, they continue to flirt with crises and have been engaged in low-intensity conflict in the disputed territory of Kashmir. This has unfolded in an environment devoid of any robust crisis management mechanisms aimed at reducing the risk of inadvertent escalation and providing dependable ways of directly negotiating a way out of a crisis. With nuclear weapons in the mix, the consequences of escalation could be catastrophic—and the possibility of such an outcome is greater today than it was on the eve of the Mumbai attacks.

India and Pakistan came “fleetingly close” to war during the Mumbai crisis, but fortunate circumstances prevented a military clash. The attacks came on the back of the single most promising peace process the two have ever had. The overall aura of positivity and the trusted channels of communication created through their five-year peace bid helped relieve tensions. A dovish Indian prime minister, Manmohan Singh—who was genuinely interested in peace with Pakistan and hesitant to use military force to settle disputes, especially in South Asia’s nuclearized environment—also led India to forego the military option, even as the Indian public and media were calling for blood. Most importantly, third-party states, led by the United States, played crucial mediatory roles and were instrumental in nudging India and Pakistan to end the crisis.

This third-party role is often glossed over—partly because neither India nor Pakistan wants to acknowledge how heavily they tend to rely on outside actors in crisis moments despite being nuclear powers.

This third-party role is often glossed over—partly because neither India nor Pakistan wants to acknowledge how heavily they tend to rely on outside actors in crisis moments despite being nuclear powers.

And yet, the centrality of U.S. crisis management in nuclear South Asia has been not only consistent but also a vital substitute for the missing bilateral escalation control mechanisms between India and Pakistan. Washington was also critical to crisis termination in the previous major crises under the nuclear umbrella: a 1999 limited war in Kashmir and a 10-month military standoff in late 2001 and 2002. U.S. success in all these cases was dependent on its ability to use real-time intelligence to clarify misunderstandings between the two antagonists and to step in with a mixture of threats and concessions to force them to pull back at moments when war seemed inevitable.

None of the pacifying dynamics at play in the past necessarily hold today. The Mumbai attacks abruptly ended the peace process itself. Since then, bilateral tensions have remained high. Diplomatic dialogue between the two remains suspended. India’s nationalist government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made total cessation of cross-border militancy emanating from Pakistan a prerequisite for formal dialogue.

India and Pakistan have also failed to conclude any confidence-building measures on terrorism over the past decade. Prior arrangements, like the joint anti-terrorism mechanismthat was concluded in 2006, lie dormant. Attempts to collaborate on investigations of terrorist incidents, including of the Mumbai attacks, have failed, with both sides blaming the other. This puts India and Pakistan in a decidedly worse position to work together to thwart potential crisis triggers or to manage risks during crises than they were in on the eve of the Mumbai attacks.

At the same time, terrorism remains an ever-present danger. Even though no attacks on the scale of Mumbai have occurred since, Lashkar-e-Taiba and other anti-India terrorist outfits in the region remain active. Pakistan claims it lacks the capacity to neutralize these groups, arguing that it has had to channel all its counterterrorism focus and resources to fighting the existential threat posed to it by the Pakistani Taliban and other domestically focused groups. However, India alleges continued active Pakistani support for militants and frames their periodic strikes on Indian soil as directed by the Pakistani state. Indian leaders therefore feel justified in directly punishing the Pakistani state for the anti-India terrorism perpetrated by these groups.

Other transnational terrorist outfits, such as the Islamic State and al Qaeda, have also expanded their footprint in the region, further complicating the threat spectrum for both countries. These groups are sworn enemies of both states, and their goal of destabilizing the region would be well served by thrusting the two nuclear neighbors into war. Hindu extremist forces in India could also spark a crisis. These forces, increasingly emboldened within India under Modi, have previously targeted Pakistani citizens in a bid to derail India-Pakistan relations. Pakistan has been increasingly vocal and aggressive in alleging Indian support of terrorist incidents in Pakistan.

Terrorism isn’t the only worry. The “Line of Control” that divides Indian and Pakistani control of Kashmir is also a likely flashpoint. Violence levels along the Line of Control were the highest in 15 years in 2017, with violations of a cease-fire agreed to in 2003 consisting of prolonged and often significant military hostilities.

#Malala, the girl who wouldn't take 'no' for an answer

By Julie Power & Pallavi Singhal

In the car on Monday night on her way to see the international activist for girls' education known simply as Malala, eight-year-old Sofia Carter of Kellyville asked her mother if the event would change her life.

"It might, darling, if you let it," Sofia's mother Maryanne Carter replied.

Malala Yousafzai acknowledges the ICC crowd in Sydney on Monday night.CREDIT:WOLTER PEETERS

When she took the stage, Malala Yousafzai said nobody was too young to make a difference. "Do not let your age stop you from changing the world," she said.

"I was 11 years old when I started speaking out ... I was not thinking for a second that just because I was young I could not change the world."

Ms Yousafzai was in Sydney to stand for the 130 million girls who were not in school around the world. "I was one of them," she told the audience.

She remembered the day nearly 10 years ago in December 2008 when the Taliban announced its plan to ban girls from going to school in the Swat Valley in Pakistan.

Girls were limited to the four walls of their houses. They couldn't be human.Malala Yousafzai

"I still remember that day, that time, when I thought I was losing my dreams. No girl would be allowed to go to school. No girl had the right to become a doctor, a teacher or an engineer. Girls were limited to the four walls of their houses. They couldn't be human," she said.

Ms Yousafzai said she couldn't believe it wasn't a dream. But that day came, and she and another 5000 girls in her area couldn't attend school.

Malala Yousafzai on Monday night.CREDIT:WOLTER PEETERS

"Education is the future for girls, the future of women," she said to the young crowd at the ICC in Sydney.

When she met girls in refugee camps, she said, they too had dreams. They knew education could change their lives.

Like the many mothers and daughters among the 8000 people who flocked to see the 21-year-old - the first time she has visited Australia - Ms Carter wanted her daughter to hear Malala's "courageous" story. "I want (Sofia) to know that not everyone lives like her, and she needs to stand for something more than just herself," Ms Carter said.

Now studying at Oxford University, Ms Yousafzai came to fame when she survived an assassination attempt in Pakistan by the Taliban in retaliation for her blog posts criticising the extremist group for banning girls from going to school.

Despite a shot to the head and extensive surgery, she continued to campaign for girls' education, establishing the Malala Fund with her father. In 2014, when she was 17, she became the youngest person to win the Nobel Prize, splitting the award with another young activist. Since then, she has won nearly every humanitarian prize that exists, from the Philadelphia Liberty Medal, the United Nations International Children's Peace Prize and another named in Mother Teresa's honour. She's also had an asteroid named in her honour, "316201 Malala" .

To many young women and girls attending the event, Malala - as they call her - is the girl who wouldn't take "no" for an answer and "didn't care what others thought".

Mariama Bah, 13, who is in year 7 at Chester Hill High School in Sydney's west, said her dad first told her about Ms Yousafzai's shooting and didn't think she would survive.

"I love that even though they said no and even with the oppression, she kept fighting," Mariama said.

"She still went on, even though she got shot in the head, that's the most inspirational thing, she's amazing."

"She still went on, even though she got shot in the head, that's the most inspirational thing, she's amazing."

The school brought about a dozen students from its student representative council to listen to Ms Yousafzai speak.

Ms Yousafzai was only 11 when she started blogging about the Taliban, even then realising it would likely trigger an attack on her life.

Mariama Bah and Zeenat Razak, both 13, are in year 7 at Chester Hill High School.CREDIT:WOLTER PEETERS

"I used to think that one day the Taliban would come [for me]," she told Glamour magazine. "And I thought, What would I do? I said to myself, 'Malala, you must be brave. You must not be afraid of anyone. You are only trying to get an education—you are not committing a crime'.

"I would even tell [my attacker], 'I want education for your son and daughter'."

Her fear was grounded. In October 2012, Ms Yousafzai, then 15, was shot in the head by the Taliban - she is now deaf in one ear - on the bus home from school.

For Chester Hill High's deputy principal Julia Cremin, it was important for her students to hear about the importance of education.

Maryanne Carter with her daughter Sofia before Monday night's talk.CREDIT:WOLTER PEETERS

"We have about 60 different nationalities represented at our school and a large number of our students have refugee or similar status and we thought it was important for them to hear a girl from a similar region to theirs talk about the importance of education," she said.

Ms Yousafzai has been 13-year-old Zeenat Razak's hero since she first heard her story. "She's such an inspiration, fighting against pressure from the Taliban, even though they said no education, she still fought for it," said Zeenat, who is in year 7 at Chester Hill High.

Ms Yousafzai was brought to Australia by The Growth Faculty as part of the Women World Changers series and she will also appear in Melbourne on Tuesday night. She is in Australia to continue her campaign for every child to go to school.

As co-founder of the Malala Fund, she is building a global movement of support to ensure girls have access to 12 years education.

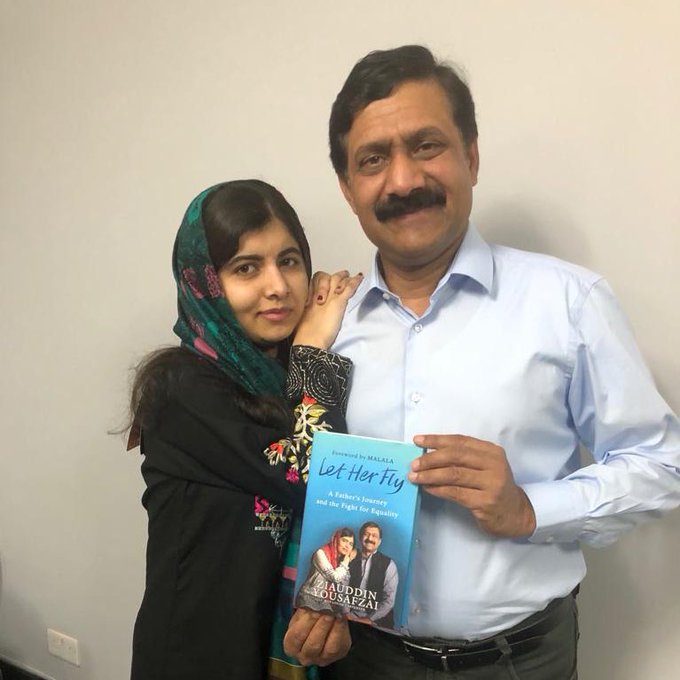

Always proud of my father @ZiauddinY, but today I’m especially so. His new book “Let Her Fly” is available now http://bit.ly/2PO9qAA

Ms Yousafzai said the fund now invested in local change makers in dozens of countries. "In some places, girls can only go to school if there are female teachers, in other places it is a need to increase Indigenous education. This is a big, big mission, and I hope everyone will think about it, and think how they can help," she said.

"If you give an education to a girl, you are changing their life and the world, too. It is one of the best investments you can make,” she said to a round of applause.

The extremists have shown what frightens them most - a girl with a book.

We must rebuild these schools immediately, get the students back into their classrooms and show the world that every girl and boy has the right to learn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1424685

On the day before the Taliban's edict took effect, she wrote in her blog nearly 10 years ago that she was discussing homework with a friend "as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened".

"Today, I also read the diary written for the BBC (in Urdu) and published in the newspaper. My mother liked my pen name 'Gul Makai' and said to my father 'why not change her name to Gul Makai?' I also like the name because my real name means 'grief stricken'," she wrote then.

Asked on Monday night in Sydney how the Taliban changed her life, she said before then, she played mock weddings. "And my brothers and other boys played police-and-thief game. When (the Taliban) came, (that game) converted into the Taliban versus the army," she said.

"You lose your childhood because you don't feel safe when you go outside because you are girl, you can't listen to music or watch TV, when all these things are taken, it is a difficult life."

Ms Yousafzai is now in her second year at Oxford studying politics and philosophy. She says she is treated like every other student and was making friends. Asked what she missed now she is living away from home, she replied "laundry". "I go home once or twice a term to wash my stuff," she said. "I get to enjoy the food and take the clean clothes back home with me."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)