M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Sunday, December 16, 2018

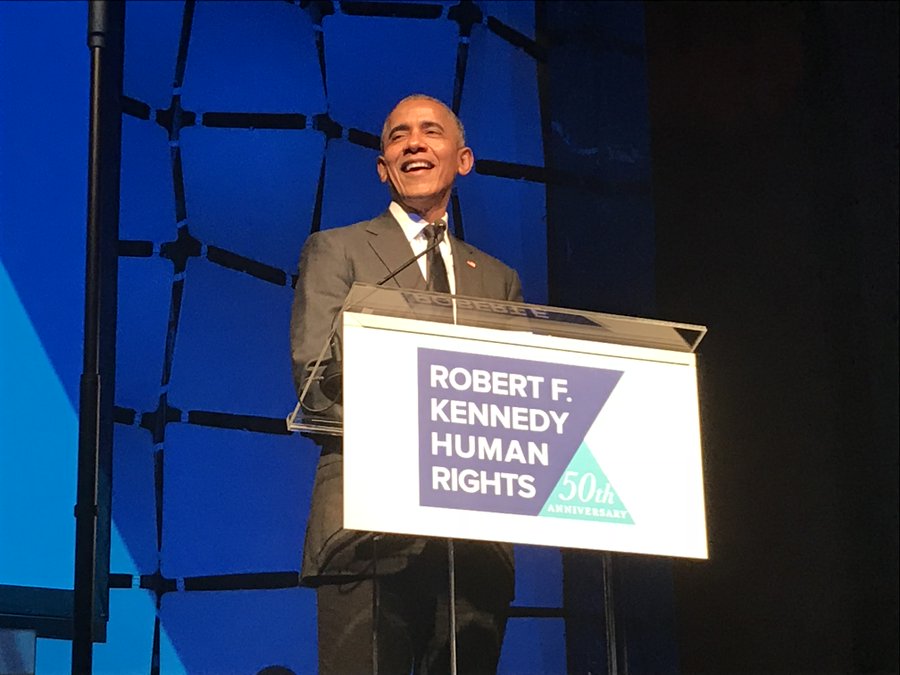

Obama honored with RFK Human Rights award

By Veronica Stracqualursi

President Barack Obama was honored Wednesday night with the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights' Ripple of Hope award at a gala in New York.

"I'm very humbled by this honor. I'm not sure if you've heard but I've been on this hope kick for a while now," Obama said in his speech Wednesday to laughs from the audience. "I gave a big speech on hope. I ran a couple of campaigns. Hope. It's my kind of thing. ... So I'd like to thank all of you for officially validating my hope credentials."

Later in his remarks, Obama said, "It can be tempting to succumb to the cynicism, the belief that hope is a fool's game for suckers."

"And worse, at a time when the media is splintered and our leaders seem content to make up whatever facts they consider expedient, a lot of people have come to doubt even the very notion of a common ground, insisting the best we can do is to retreat into our respective corners, circle the wagons and then do battle with anybody who is not like ourselves," Obama said. "Bobby Kennedy's life reminds us to reject such cynicism."

Discovery CEO David Zaslav, Humana CEO Bruce Broussard and New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy were also honored with this year's Ripple of Hope award.

"As Bobby Kennedy taught us, the thing about hope is that it travels through space *and* time, first splashing against the rocks, but eventually breaking down the walls of cruelty and injustice," Obama wrote on Twitter Wednesday night echoing his speech. "And if we do our best with the time we're given, others will take hope in our example."

As Bobby Kennedy taught us, the thing about hope is that it travels through space *and* time, first splashing against the rocks, but eventually breaking down the walls of cruelty and injustice. And if we do our best with the time we’re given, others will take hope in our example.

50K people are talking about this

Kerry Kennedy, the organization's president and daughter of Robert Kennedy, presented the 44th president with the award for those who have "demonstrated a commitment to social change."

"Bobby Kennedy was one of my heroes," Obama said in a statement back in August when it was first announced he'd be receiving the award. "He was someone who showed us the power of acting on our ideals, the idea that any of us can be one of the 'million different centers of energy and daring' that ultimately combine to change the world for the better."

"I’m not sure if you heard, but I’ve been on this hope kick for quite awhile."

President @BarackObama delivers a message of hope at the 2018 #RippleofHope Gala. #RFK50

59 people are talking about this

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the organization RFK Human Rights' founding and Kennedy's historic campaign for the White House.

Past recipients of the Ripple of Hope award include Hillary Clinton, Bill Clinton, Joe Biden, Al Gore, John Lewis, Robert De Niro, Taylor Swift and George Clooney.

Hillary Clinton writes letter to 8-year-old girl who lost class president to male classmate

BY AVERY ANAPOL

Former Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton penned a personal letter to an 8-year-old girl who lost her race for class president to a boy.

Clinton wrote to console Martha Kennedy Morales after the third-grader lost the election by a single vote, according to The Washington Post, which confirmed the letter's authenticity with a Clinton spokesman.

“As I know too well, it’s not easy when you stand up and put yourself in contention for a role that’s only been sought by boys,” Clinton wrote in the letter.

Morales’s father posted updates about his daughter’s campaign on Facebook, which caught the attention of someone close to Clinton.

Morales said she lost her election to a popular fourth-grade boy in her mixed-grade class at Friends Community School, a private Quaker school in Maryland. She was named vice president after six ballots were found to be filled out incorrectly, losing a second election by one vote.

“While I know you may have been disappointed that you did not win President, I am so proud of you for deciding to run in the first place,” Clinton wrote to Morales. “The most important thing is that you fought for what you believed in, and that is always worth it.”

“As you continue to learn and grow in the years ahead, never stop standing up for what is right and seeking opportunities to be a leader, and know that I am cheering you on for a future of great success,” the former first lady, senator and secretary of State wrote.

The 8-year-old told the Post that she was “very surprised” to get a letter from Clinton, who was the first woman to be a major party’s presidential nominee.

#Bangladesh - Victory Day: Written by hand, driven by heart

By Wasim Bin Habib and Rejaul Karim Byron

October, 1971.

The war waged by the Pakistani occupation army on Bangalees had just entered its eighth month.

Unimaginable brutalities and carnage -- countless deaths, millions displaced and a trail of destruction -- were all over the then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

And in the ruins the resistance against the brute Pakistan force was growing in every nook and corner, with thousands taking up the arms and a few others embracing weapons of a different kind to liberate their beloved nation.

One day, a group of young people in a small village in Nawabganj felt the urgent need of a weekly publication to unite the locals against the marauding army's crackdown and killings.

They launched Saptahik Bangladesh to spread the flames of freedom among the people of the greater Bikrampur.

In its 70-day life-span, the weekly mirrored the tumultuous days of 1971 and published local and international news about the Liberation War.

"I cannot explain how difficult it was to publish a newspaper at the time. We were living on our nerves every moment as we published the newspaper," said Mizanur Rahman, a freedom fighter entrusted the task of editing and publishing the weekly from a secret place.

Now 73-year-old, Mizanur, a businessman, talked about the extraordinary episode of bringing out the newspaper with The Daily Star at his Eskaton office.

"I was a teacher and people in the area used to respect me," said Mizanur, who passed matriculation from a school in Kolaroa of Satkhira in 1965 and joined Churain High School in Nawabganj as a teacher in 1969.

The crew involved with the newspaper was at risk of being attacked all the time, he said.

"Besides, collecting the paper and other materials from Dhaka was extremely risky."

His colleague and fellow freedom fighter Abdus Salam took the risk and left for Dhaka on what he now thinks was October 23.

“Salam returned and came to my home the next day with the necessary paper, printing ink, stencils and other materials. It was like we achieved our first victory."

The next challenge was to manage a cyclostyle, a device that makes stencil copies with its small-toothed wheels on a special paper that which serves as a printing form.

Head teacher of the school Shaktipada Chowdhury made the job easy. He gave the school's cyclostyle to the publishers.

The office of the newspaper was set up at a room in Mizanur's rented house. The first issue was published on October 31.

The writers used pseudonyms. Mizanur was Kirti.

The printer's line of the weekly shows "Kirti" as the editor and "Torit" as the printer. The newspaper was published and circulated by "Biplobi Parishad".

Shahidullah Khan was the news editor and Abdul Baten was the chief reporter. Kaikobad and Mohammad Israfil were the sub editors and Rafiqul Islam and Niranjan were reporters.

Each issue had Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's speeches printed just below the masthead. The paper, except the first four issues, had a sketch of Bangabandhu just beside the masthead and a map of Bangladesh beneath it.

The content mostly depicted the struggle of people, brutalities of the Pak forces, and stories of successful operations and victory of the freedom fighters at different fronts.

The newspaper's editorial, columns, international news and poems were a huge source of inspiration for the common people, he said.

"I used to write a column titled Drishtikon and Mukjodhhar Dairy Theke under my pseudonym."

He became seriously involved in politics in 1965 when he was enrolled in Munshiganj's Haraganga College, a famous institution.

At least 10 teachers of his school would collect news from local and faraway places. Two others were dedicated to collect international news about the war from the radio.

Image of the first issue of the Saptahik Bangladesh, a weekly published in Bikrampur in 1971.

Apart from the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra, they used to get reports from BBC, Voice of America and Akashbani.

"We all were young and our emotions ran very high. We used to give a portion of our salary for the expenses of bringing out the newspaper. A number of local people would also donate money sometimes."

Even in those days, the headmaster ensured the regular salary of the teachers every month, he added. "My monthly salary was Tk 160."

Mizanur could not recall the exact amount they would need to bring out the newspaper. But he said one rim of paper would cost around Tk 45 or 50 and a tube of ink Tk 50.

In the initial few weeks, they would print 150 to 200 copies and then increased the publication to around 400 to 500 copies. The highest number of copies that they could bring out was around 1,200, he said.

"Starting from the afternoon, we used to print the newspaper throughout the night."

The price they fixed for each issue hovered between Tk .12 to .25.

"But we used to distribute the paper for free as well, because our main objective was to mobilise a strong public opinion about the atrocities and to lift the morale of the freedom fighters."

Mizanur was the Chhatra League president in Munshiganj subdivision unit and senior vice president of Dhaka district unit in 1967.

"We usually did not verify the reports and ran those that went in favour of freedom fighters. There was practically no scope to cross check those."

One day, they had to flee to Arial Beel with the cyclostyle as they heard that the Pak force was coming to their area.

"That night, we hid in a boat and published the newspaper from there.

"There were many other challenges and concern of losing life, but we continued publishing the newspaper fearlessly," he said, adding that the brief stop-over of Tajuddin Ahmed and his emotional speech in Churain inspired them the most.

The prime minister of the then government in exile in Mujibnagar attended an armed training of the freedom fighters at Churain High School playground on March 27 before heading for Faridpur the next day, said Mizanur.

Mizanur also travelled to Mujibnagar and then to Kolaroa, his birthplace. From there, he went to Bithari of North 24 Parganas district in West Bengal before returning to Nawabganj in mid August to devote himself in organising the war.

The last Saptahik Bangladesh came out on January 8, 1972.

https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/news/victory-day-written-hand-driven-heart-1674328

#Bangladesh - After the war - Some wounds don’t heal

By Shilpi Rahman

As a precocious pre-teen, I had a hidden world of my own, to which only I had access.

Here, I had my own joys and sorrows, and my own secret language. Maybe this language would be unintelligible to others, maybe it wouldn’t. It was a window into my secret world, and I didn’t have the courage to share the key.

It’s easier for me to talk about this now -- back then, it was impossible. Baba used to emerge from the bathroom, freshly showered, leaving behind the scent of his aftershave. The smell of it lingers in my mind, one of the precious few memories I have of him, and I hold it close, because I can’t let it fade. It gives me comfort.

Within this secret world, I held on to a complicated conviction. I was still searching for my father, and I had convinced myself that he would return to us one day. I could picture his right hand hovering over us all, as though to dispel our fears and pledge his return, and I was the secret witness to that pledge.

I waited for the day he’d make true on that promise. I told myself he had lost his memory during the heat of battle and forgotten us. Someday, it would return to him in a flash.

We’d be seated at dinner and there would be a knock at the door, and we’d open it to find a man with a long beard, wearing a white panjabi and tears of joy in his eyes at having finally found us again. I could never envision beyond this moment. All my fantasies would end at this point, but I kept revisiting them, as though to mend some frayed wires.

I was so young when they took him away, I don’t have clear memories. Whenever an event of great import happened, I would join in to see what was happening. One day, I saw that two of the razakars who had taken my father away had been caught and brought to our door. Their hands were tied behind their backs, and they were to be put on trial for their crimes, but brought for us to see them one last time.

I saw some people spit on their faces, others swear at them, and still others throw in a slap or punch. As if that would recoup our losses. My father wasn’t coming back. My mother hadn’t stopped weeping. We had nowhere to go. There was hardly any food. We spent our days in uncertainty. Word had been sent to Dhaka, and we waited for someone to come and rescue us.

Our area had been liberated the day after my father’s death. I feel as though if he had managed to stay alive just one more day, our lives would have been different. At that time, Bangladesh was achieving liberation one area at a time. The Pakistan army had got their hands on a list of our intellectuals.

They went to places where these intellectuals lived or were rumoured to be staying, to finish them off. A lot of ordinary people also died in the process. The Pakistani army brutally slaughtered most of the intelligentsia on December 14. They knew perhaps that they were losing, and so decided to break our backbone before retreating, so that we as a nation would never be able to stand on our feet. But they had underestimated the Bangalis.

Sixteen days later, my maternal cousin arrived from Dhaka to take us away from the little village in Ghorasal, where we’d been staying. I felt that they had arrived to add to the mourning party. People wept day and night, and fainted often. We had to procure smelling salts from the nearby medicine shop to revive those who swooned, but they’d wake up only to swoon again. My eldest sister and my grandmother fainted most often. My mother had probably turned to stone by then. Once one enters the battle for life, there is no room for tears.

The more one understands what one has gained or lost, the more one is plagued by a need to seek answers and find closure. The uninformed don’t have that worry. I don’t know what memory specialists have to say about early childhood memories, but the clarity with which I remember certain events from so far back amazes even me. That I can astound my family members with such vivid recollections fills me not with pride, but wonder.

I can’t explain it, but my theory is we all have certain hidden memories that a certain amount of trauma or triggering event can bring to our conscious minds to create new connections. I get hazy mental images sometimes, sparked off by a photo, or event. These come into sharp focus when I concentrate on remembering, gaining colour and shape until a page out of my personal history emerges.

The stories I tell today are partly based on some of my own recollections, which gained meaning for me long after the actual events themselves, some as I attained maturity, and others based on stories I heard growing up.

'We're All Handcuffed in This Country.' Why Afghanistan Is Still the Worst Place in the World to Be a Woman

By LAUREN BOHN

It was a sunny morning in early December last year when 23-year-old Khadija set herself on fire. She kissed her three-month old son Mohammed goodbye and said a short prayer.“Please God, stop this suffering,” she pleaded in the sun-soaked courtyard of her home in Herat, Afghanistan as she poured kerosene from a copper lamp over her small frame. She then struck a match. The last thing she heard were birds chirping.The next morning, she realized her prayer had gone unanswered. Khadija, who asked TIME not to publish her last name or her family’s, woke up at Herat Hospital in Afghanistan’s only burn unit, her body blanketed in third-degree burns and bandages.

“I am not alive, but I am not dead,” Khadija told me later that week, crying and gripping the hands of her sister, Aisha. “I tried running away and I failed.” Like the majority of Afghan women, Khadija was a victim of domestic abuse. For four years, she said, her husband beat her and told her that she’s ugly and dumb – “a nobody.”

“Women never have any choices,” Khadija said last December in the hospital, as tears streamed down her face, a barely recognizable charred patchwork of fresh scars. “If I did, I wouldn’t have married him. We’re all handcuffed in this country.”Khadija’s decision to set herself on fire prompted her husband to be arrested on charges of domestic violence, an unusual situation in a country where abuse against women is rarely criminalized. But even while he was serving his prison sentence, Khadija felt more trapped than when she tried to take her own life. Her husband’s parents, who were looking after her son, issued Khadija an ultimatum: If she would tell the police that she lied—that her husband didn’t actually abuse her—and if she returned home, then she could see her son. If she refused, she would never see him again.

In a country racked by decades of war and a dearth of resources, Khadija’s story shows how women in Afghanistan are struggling to live with dignity. It also highlights how, in the face of little governmental support and dwindling international aid, women are stepping in to help one another.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this for Afghanistan, the country of 35 million people where America has waged its longest war. The war was billed, in part, as “a fight for the rights and dignity of women.” The Taliban ruled in Afghanistan from 1996 until 2001, a period in which women were essentially invisible in public life, barred from going to school or working. In a 2001 radio address to the nation, First Lady Laura Bush urged Americans to “join our family in working to ensure that dignity and opportunity will be secured for all the women and children of Afghanistan.” In 2004, President George W. Bush declared victory in the country.

But seventeen years and almost $2 trillion later, the country is still in turmoil as the Taliban maintains its grip on almost 60 percent of the country, the most territory it has controlled since 2001. In October, the U.N. said Afghan civilian deaths were the highest since 2014: from January to September 2018, at least 2,798 civilians were killed and more than 5,000 others injured. Gallup’s most recent survey of Afghans, conducted in July, revealed strikingly low levels of optimism: Afghans’ ratings of their own lives are lower than in any country in any previous year.

As in all war-torn societies, women suffer disproportionately. Afghanistan is still ranked the worst place in the world to be a woman. Despite Afghan government and international donor efforts since 2001 to educate girls, an estimated two-thirds of Afghan girls do not attend school. Eighty-seven percent of Afghan women are illiterate, while 70-80 percent face forced marriage, many before the age of 16. A September watchdog report called the USAID’s $280 million Promote program – billed the largest single investment that the U.S. government has ever made to advance women’s rights globally – a flop and a waste of taxpayer’s money.Government statistics from 2014 show that 80 percent of all suicides are committed by women, making Afghanistan one of the few places in the world where rates are higher among women. Psychologists attribute this anomaly to an endless cycle of domestic violence and poverty. The 2008 Global Rights survey found that nearly 90 percent of Afghan women have experienced domestic abuse.“It hurts me to say this, but the situation is only getting worse,” said Jameela Naseri, a 31-year-old lawyer at Medica Afghanistan, an NGO established by German-based Medica Mondiale, defending women and girls in war and crisis zones throughout the world. Naseri oversees Khadija’s case, as well as the cases of dozens of other women who are seeking refuge or divorce from allegedly abusive husbands. In the face of what she calls “a war against women,” she is leading an informal but determined coalition of female psychologists, doctors and activists in Herat who take on cases like Khadija’s.

“I meet a new Khadija almost every day,” she said, while fielding a call from an activist. Earlier that week, a man claimed his wife had died from a longstanding illness but activists suspect he murdered her. “We do the best to help these women, but sometimes we can’t. That’s hard to accept.” Herat, a province in western Afghanistan near the border of Iran, has some of the highest rates of violence against women in the country and some of the highest rates of suicide among women. Psychologist Naema Nikaed, who was working with Khadija, said she handles several cases of attempted suicide every week. Most go unreported due to fear of tarnishing a family’s honor. “The government wants to say they’re prioritizing women,” a female Afghan diplomat told me, speaking on condition of anonymity during the NATO Summit in Brussels in July. “But they’re really not. Supporting women in Afghanistan is something people all over the world pay lip service to, but money and aid never get to them. It’s eaten by corruption, the monster of war.” Transparency International ranked Afghanistan the fourth most corrupt country in the world, noting that corruption hampers humanitarian aid from getting where it needs to go. At the NATO summit, I asked President Ashraf Ghani why two-thirds of girls are still out of school. He largely blamed the numbers on ill-conceived, misguided Western aid efforts that fail to acknowledge the realities on the ground.

“To get to the very nitty gritty, how many girls schools at the age of puberty have a toilet? That’s fundamental,” he said. “How many girl schools are three kilometers away? The issue here is that international experts were male-centric. They talked about gender but their pamphlets were glossy and totally lacking content.”

But activists say his administration has failed to take responsibility for clear backslides in women’s rights. In 2015, 27-year-old Farkhunda Malikzada was beaten to death by a mob in Kabul after being falsely accused of burning the Quran. The government did little to mete out justice and ignored demands for more action to combat violence against women. What’s more, in February 2018, Afghanistan passed into law a new criminal code that the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) hailed as a milestone in the country’s criminal justice reform. However, one chapter of the code was removed before it was passed: the chapter penalizing violence against women. In June, a United Nations report took the Afghan criminal justice system to task for ignoring violence against women.

“Women’s rights were supposed to be the success story of the 2001 invasion,” Naseri said. “But the legacy of war is still killing our women.”

Naseri knows this legacy all too well. Her own mother was forced to marry her father when she was only 12 years old and says she was then abused for years. In order to go to school, Naseri and her mother crafted lies so that her father would let her leave the house. They told him she was going to the mosque or to Quran studies. School wasn’t a place for girls, he contended. Eventually, they convinced him to let her attend university; she became the first and only woman in her family with a degree.

In the face of so much oppression, Naseri vowed to become a lawyer and help women like her own mother and sister, who was forced into marriage at the age of 14.

“Afghan women need to take matters into our own hands. We can’t wait for the government and international charities to save or liberate us,” she said in her office at Medica. Across the hall, a 16-year-old girl named Sahar sat waiting to speak to Naseri. Her mother brought her to Medica after she tried to jump off the sixth-floor balcony of their building. She was to be married off to her cousin in days, and said her uncle had been raping her since she was just 10.

“In doing this work alone, the risks are high. At any moment, we could be killed,” Naseri said. Not a week goes by, she said, that she doesn’t receive death threats. Just last year, an angry mob of men came to the center threatening to burn it to the ground, claiming Naseri was promoting divorce and damaging the fabric of Afghan society.“I know what it’s like to be the victim,” Naseri said. While at university, she fell in love with a classmate. She says she is the first woman in her family whose marriage wasn’t arranged.In March, on International Women’s Day, she gave birth to a boy. “I refuse to bring my son into a world where he thinks women are second-class citizens.”

Last December, the halls of Herat Hospital were lined with patients sitting on the floor, waiting for assistance. Everything is off-white: the chairs, the walls, the floors. Moans of pain echo through the hospital’s burn unit.

Khadija’s doctor, 29-year-old Hasina Ersad, visited her a few times a day for months. “I saw women like Khadija all my life,” said Ersad. “She’s the reason I wanted to become a doctor.”Khadija said her abuse began as soon as she got married. Her father, Mohammed, was poor and sold her off. Her husband promised her that she could go to school and pursue her goal of becoming an esthetician, but by the first week of marriage she learned that would likely never happen. Her mother-in-law told her that her purpose was to raise children. After several miscarriages, she finally gave birth to her son, Mohammed. She thought the abuse would stop once he arrived, but it only got worse.Khadija’s sister Aisha said domestic abuse is pervasive. “My husband has hit me for years,” she shrugged.

Aisha’s husband is 71 years old; she is 26. Over the years, she said she has thought about getting a divorce, but she knows the reality: she’d lose custody of her three children and likely never marry again. In cases of divorce, women have custody of their children up until the age of 7, then children are given to their fathers.

“We weren’t lucky girls,” Aisha said as Khadija struggles to nod in agreement. “Actually, no girl in Afghanistan is lucky.”

Khadija’s psychologist Naema Nikaed, one of the few in Afghanistan who counsel suicide survivors, said she and her colleagues have witnessed an uptick in suicides among women over the past few years.“If the government doesn’t start prioritizing the lives of women, then we will be in a forever war here in Afghanistan,” she said. Earlier that day, Nikaed had visited a 15-year-old patient who overdosed that morning on unidentified tablets from a pharmacy.“It’s really only up to us – the women like Jameela, myself and others – to fight this discrimination and to save lives. No one can save us but ourselves.”When Khadija was three, her mother died from childbirth complications, leaving their father Mohammed to raise Khadija and her four siblings. (Afghanistan has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world.)

“I always wanted to give my daughters a better life, but how could I?” Mohammed asks as he waits on a bustling street corner to find daily labor. It’s a cold December morning and he and other men warm their hands over a makeshift fire. He’s only 50 years old, but his face prematurely droops from years of depression and destitution.

Both of Mohammed’s parents died when he was one; he said he grew up with an abusive uncle who stole his land. “War has affected this whole country,” he said. “It’s all we know and it has made us broken and blind.”

When Khadija was 15, he began shopping around for dowries. The highest bid came from a working-class family in Herat with a “good enough” reputation. Mohammed received $3,400 for Khadija. Mohammed said he understands that his daughter is unhappy, but that she has no choice. Even if her husband is abusive, he is resolute about what his daughter should do: she must stay with him. “I can’t take care of her. I wish I could, but she’s better off with them,” he said. “Trust me, she’s better off.”

To get to Khadija’s and her parents-in-law’s home, you pass through a maze of trash-strewn streets and small corner shops selling nothing more than soda and chips. On the corner, there’s a tiny pre-school filled with little boys in blue shirts next to a beauty store where sometimes Khadija would work – her only reprieve from home life. In the family’s small living room, Khadija’s in-laws told me their son “never touched” Khadija and that because of her, they had lost their reputation. When their son called them from prison, where he was granted one call a day, he told me he was an innocent man.

Naseri’s close friend, Hassina Nikzad, the director of Afghan Women’s Network, visited Khadija weekly and reminded her that she could file for a divorce. “But where will I go? Mom is dead and dad is old,” she cried to her sister, Aisha.

Nikzad suggested that she could move to a shelter and learn a trade like tailoring. Khadija shook her head and looked down.

Last December, Nikzad told me she wasn’t sure Khadija would go through with the divorce. “It’s often easier to stay with the pain. Starting a new life in Afghanistan seems impossible,” she said. “We’re not given any chances, let alone a second chance.”

Last June when Khadija left the hospital, she wearily told Naseri that she had made up her mind. Although Naseri suggested she move to a shelter, Khadija decided to return to her husband’s parents. The pain of not seeing her son was too much to bear and raising a child in a shelter seemed too daunting.But after a month of living with her parents-in-law, Khadija called Naseri in the middle of the night, crying. Her parents-in-law had refused to let her touch her son, Khadija said. And her husband kept saying that he planned to “punish” her when he was released from prison.

Because there was no adequate shelter space in Herat, Khadija decided to stay in her father’s one-room apartment. But her step-mother made it clear that Khadija wasn’t welcome there.

“I don’t regret doing what I did, but I’m still in chains,” Khadija told me in November over Skype. She hadn’t seen her son in months. “One day, I will try to explain to my son why I did this. I hope he understands.” Naseri held her as she sobbed.

In late November, Khadija’s husband was released from prison. Soon after, Naseri tried to contact Khadija but couldn’t reach her. Her phone has been turned off since. Naseri suspects Khadija fled across the border to Iran. It’s unlikely she will see her son again—at least not for a while.

To Naseri, Khadija is one of far too many invisible victims in the country’s war against women. “I could have been Khadija,” Naseri said. “Who knows what separates us? Nothing does.”

India, Pakistan, and the Kartarpur Corridor

By Grant Wyeth

It is no great claim to state that India and Pakistan have always struggled with the complexities that were established by the 1947 border. Instead of facilitating a separation, the partition persistently highlights the realities of a shared past, and continues to present new ways both countries seek to negotiate this dilemma. While an issue like the disputed territory of Kashmir can seem almost intractable, there are areas of shared interest between the two countries where they are capable (albeit stubbornly) of forming agreements, building trust, and making progress toward greater stability.

One of many problematic outcomes of the 1947 partition of India — and its creation of Pakistan — was that a number of sites of religious significance to the region’s three main religions became located on either side of the division. This created a significant tension between the religious aspirations of the two countries’ citizens and the new hard border now placed in front of them.

This became especially troublesome for followers of Sikhism. For Sikhs, the partition of India posed a deep existential headache. Sikhs overwhelmingly chose India over the newly formed Pakistan as the state that would best protect their interests (there remain around 20,000 Sikhs living in Pakistan today, compared to around 21 million in India). However, in making this choice Sikhs became isolated from a number of their holiest sites, as well as their cultural, and former political, capital of Lahore. This has generated a westward yearning for the community that the border only intensifies.

While the Sri Harmandir Sahib (or Golden Temple) in the Indian city of Amritsar remains Sikhism’s most important religious site, three sites (gurdwaras) deeply connected to the life of the religion’s founder, Guru Nanak, are now in Pakistan. The Gurdwara Janam Asthan, west of Lahore, is situated on the location where Guru Nanak was born, and the Gurdwara Panja Sahib in the town of Hasan Abdal is believed to have the handprint of Guru Nanak imprinted on a boulder within its grounds. And lying just 4 kilometers across border is the Gurdwara Darbar Kartarpur Sahib, the location of Guru Nanak’s death, and where he spent the last 18 years of his life. Such is the emotional pull of this site that on the Indian side of the border a viewing platformhas been constructed where people can use binoculars to gain a look at the temple.

India and Pakistani do have an agreement that provides a framework to approach this dilemma. The Protocol on Visits to Religious Shrines (1974) allows their respective citizens the opportunity to visit religious shrines in each country under certain conditions. Alongside Sikhism’s holy sites in Pakistan, India contains a number of sites of great importance to followers of the Sufi Islam, while Pakistani Hindus and Indian Muslims also rely on the protocol for their cross-border pilgrimages. The protocol recognizes the deep shared history that permeates the region, and understands that the cultural and religious requirements of their respective citizens need to be honored outside the strategic animosity between the two states.

However, the agreement is often held hostage to this animosity. When tensions arise both states become reluctant to issue visas to pilgrims, creating further resentment and suspicion between the countries. Yet a recent initiative, instigated by the new Pakistani government of Imran Khan, to establish more consistent access for Sikh pilgrims has the potential to build some greater trust between the two countries. With the Gurdwara Darbar Kartarpur Sahib being so close to the border, its location presented an opportunity to create a more efficient structure around visitation rights, and provide some surety for Sikh pilgrimages.

In late November inauguration ceremonies were held for a new road linking the Indian town of Dera Baba Nanak to the Gurdwara Darbar Kartarpur Sahib in Pakistan. Known as the “Kartarpur Corridor,” the road would allow for visa-free travel for Sikh pilgrims to the gurdwara. It is planned to be opened next year, in time for the anniversary celebrations commemorating 550 years since Guru Nanak’s birth. Although the plans for the corridor include a fenced roadway, creating something of a inhospitable environment for the short journey, the development will nonetheless be appreciated by Indian Sikhs, and the display of cooperation between Islamabad and New Delhi should be taken as a positive step.

Khan’s initiative, combined with an announcement that Pakistan would issue 3,800 visas for Sikh pilgrims to visit other sites in Pakistan for Guru Nanak’s birth anniversary, seems to indicate a greater willingness to reach out to India. These actions can be seen in light of what has come to be known at the “Bajwa Doctrine.” Earlier in the year, Pakistan’s army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa, made a series of speeches signalling that Pakistan was willing to take a more cooperative approach to its neighborhood relations. The analytical consensus was that a stalling Pakistani economy has the potential to become an internal security threat, and Bajwa sees that increasing trade with India may provide a solution to this problem.

While New Delhi may welcome this more conciliatory tone from the Pakistani military commander (the driving force of Pakistani foreign policy), it will also be wary that the Bajwa Doctrine itself faces a highly institutionalized combative attitude toward Pakistan’s neighbors that may be difficult to shift so easily, even with the Pakistani military’s considerable influence on public policy.

This reflex attitude was on full display when Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi boasted that Khan had “bowled a googly” to India in order to secure Indian representation at the Kartarpur Corridor groundbreaking ceremony in Pakistan. In cricket a “googly” is a ball that seems like it is going to spin in one direction but actually spins the opposite way. The use of the term indicated that India had fallen for a “trap” laid by Khan. The predictable combative response from India’s Minister of External Affairs Sushma Swaraj then threatened to derail the goodwill that had initially been established. Khan has since distanced himself from his foreign minister’s remarks, stating that the plan for the Kartarpur Corridor was a “sincere effort.”

Although Bajwa and Khan may be attempting to find a more cooperative relationship with New Delhi, Pakistan’s national psychology remains focused on proving that the idea of India, as a plural and secular society, cannot work. Pakistan was indeed born out of this notion, making it a deep existential component of the state. Due to this Islamabad has a tendency to find ways to try and intensify sensitive internal issues to annoy the Indian government.

In April, a group of Indian Sikh pilgrims were granted visas to visit the Gurdwara Panja Sahib in Hasan Abdal for Vaisakhi, Sikhism’s most important festival. However, along the route to the town Sikh separatist propaganda had been strategically placed. The posters proclaimed “Sikh Referendum: 2020 Khalistan” — a reference to a proposed referendum by the New York-based Sikhs for Justice for a separate Sikh state to be known as Khalistan. The advocated poll has no support from either the Indian government or the Punjab state government, and it seems to lack any credible way of gauging actual separatist sentiment with its focus on diaspora communities. But for Pakistan the noise presented an opportunity to try sow discontent among the Sikh pilgrims visiting their religious site.

India has long accused Pakistan of attempting to ferment separatist sentiment in Indian Punjab, and the leadership of Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) — the Sikh terrorist organization responsible for the bombing of an Air India flight from Toronto to Delhi in 1985 — is currently located in Pakistan. According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal, the organization is aided by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), as well as by Sikh diaspora groups.

Coming so soon after a tense visit by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, where issues of Khalistani sentiment in Canada dominated the agenda, New Delhi had little patience for this attempt to influence Sikh pilgrims and directly warned Islamabad that such tactics would not be tolerated. The Ministry of External Affairs issued a statement regarding the incident that explained “Pakistan was called upon to immediately stop all such activities that were aimed at undermining India’s sovereignty, territorial integrity and incitement of disharmony in India.”

Making note of the threat this posed to the Protocol on Visits to Religious Shrines agreement, the statement further added, “It was conveyed that such repeated attempts by authorities and entities in Pakistan to extend support to secessionist movements in India amount to interference in the internal affairs of India. Moreover, such incidents during the visit of the Indian pilgrims went against the spirit of the bilateral Protocol of 1974 governing the exchange of visits of pilgrims between the two countries.”

Were Pakistan to utilize such tactics again in relation to the Kartarpur Corridor the initiative would quickly be derailed. But as a new prime minister, Khan should be given time to demonstrate he is indeed sincere in wishing to make progress on the relationship with India (he wasn’t yet PM in April). However, Bajwa must understand that antagonistic actions like displaying Khalistani propaganda will only undermine his new strategic doctrine. That Bajwa was seen shaking hands with a pro-Khalistan leader at the groundbreaking ceremony for the corridor did not bode well in this regard. If Pakistan is genuine about its current outreachtoward New Delhi then its leaders will require greater vigilance and restraint in order to establish the requisite trust.

Currently that trust is lacking. Swaraj has indicated that she sees the positive developments regarding the Kartarpur Corridor as separate from the wider bilateral talks between the two countries — the latter being something that New Delhi is currently refusing to re-engage with due to continued Pakistani efforts to further destabilize India’s Kashmir region. With an election approaching in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi would also be cautious about engaging in any complex and protracted negotiations. Modi will also not attend the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) summit to be held in Islamabad this month.

As is the case with such a diverse and complex region, a potential solution to one problem usually has the knock-on effect of generating another problem. The smoother access to the Gurdwara Darbar Kartarpur Sahib for Indian Sikhs has already created demand from other religious groups for similar arrangements. Hindu Kashmiri Pandits are now hoping to gain easier access to the Sharada Peeth temple, which lies across the Line of Control (LoC) in Pakistan-administered Kashmir. Given the sensitivity of the region, this seems highly unlikely.

In this light, what the development of the Kartarpur Corridor has clearly demonstrated is that the deep shared cultural and religious histories of the region cannot be erased, only complicated by the border. It remains true that at the time of partition it was not fully understood exactly what the new border would produce. After all, Muhammad Ali Jinnah — the driving force of partition and founder of Pakistan — thought he’d be able to retire in Bombay (now Mumbai), a prospect that may have seemed plausible to him at the time, but is clearly absurd today.

The Kartarpur Corridor may be a small initiative to create some goodwill and ease one pressure on both states, and with success this may create the momentum to identify and sooth another problem in the future. Although religious tensions in the region continue to be fraught, the opportunity for more consistent and efficient access to pilgrimage sites is an area of cooperation between the two states that could prove fruitful. With increased trust and serious commitment this incremental approach may achieve some tangible results, but the overall task of rapprochement remains considerable.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)