M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Saturday, December 29, 2018

Rise of #Bangladesh: An economic success story

Bangladesh has been marred by tragedy including: the 1971 Liberation War, poverty, natural disasters—and now—one of the world's largest refugee crises after receiving an influx of 750,000 Rohingya Muslims who fled persecution in neighboring Myanmar.

However, with remarkably little international attention, Bangladesh has also become one of the world's economic success stories.

Aided by a fast-growing manufacturing sector—its garment industry is second only to China's—Bangladesh's economy has averaged above 6% annual growth for nearly a decade; reaching 7.86% in the year through June, reports Nikkei Asian Review.

From mass starvation in 1974, the country has achieved near self-sufficiency in food production for its more than 166 million people. Per capita income has risen nearly threefold since 2009, reaching $1,750 this year.

Meanwhile, the number of people living in extreme poverty—classified as under $1.25 per day—has shrunk from about 19% of the population, to less than 9%, over the same period, according to the World Bank.

‘Developing economy’

Earlier this year, Bangladesh celebrated a pivotal moment when it met United Nations criteria to graduate from "least developed country" status by 2024. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina considers the elevation of status to "developing economy" a significant boost to the nation's self-image.

Bangladesh's economic performance has even exceeded government targets on many fronts.

With a national strategy focused on manufacturing—dominated by the garment industry—the country has seen exports soar by an average annual rate of 15-17% in recent years; reaching a record $36.7 billion in the year through June.

This sector is on track to meet the government's goal of $39 billion in 2019, and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has urged industry to reach a $50 billion valuation by 2021; to mark the 50th anniversary of the Liberation War, said the Nikkei Asian Review report.

A vast community of about 2.5 million Bangladeshi overseas workers further buoys the economy with remittances that jumped an annual 18% to top $15 billion in 2018. However, Hasina also knows the country needs to move up the industrial value chain.

Political and business leaders echo her ambitions to shift from the old model of operating as a low-cost manufacturing hub partly dependent on remittances and international aid.

‘Digital Bangladesh’

Sheikh Hasina launched a "Digital Bangladesh" strategy in 2009 backed by generous incentives.

Now, Dhaka, the nation's capital, is home to a small but growing technology sector led by CEOs who talk boldly about "leapfrogging" neighboring India in IT. Pharmaceutical manufacturing—another Indian staple—is also on the rise.

The government is now implementing an ambitious scheme to build a network of 100 special economic zones around the country; 11 of them have been completed while 79 are under construction.

Tailored industrial policy

The ready-made garment industry is a key factor in the country's phenomenal success story. The industry is the country's largest employer, providing about 4.5 million jobs, and accounted for nearly 80% of Bangladesh's total merchandise exports in 2018.

It has undergone seismic changes since the watershed Rana Plaza disaster in 2013, when a multi-story garment factory complex collapsed, killing more than 1,130 workers. In the aftermath, the industry was forced by international apparel brands to implement sweeping reforms; including factory upgrades, inspections, and improved worker conditions.

Further investment is needed if Bangladesh's garment industry is to remain competitive.

Bangladesh's textile industry could benefit if China's garment exports are hit by a prolonged US-China trade war. However, other garment centers are also taking aim at a vulnerable China, including: Vietnam, Turkey, Myanmar, and Ethiopia.

Intensifying international competition has already sparked consolidation in Bangladesh's garment industry, reducing the number of factories by 22% in the last five years to 4,560, according to the BGMEA.

The government has moved to streamline the investment process with the creation of a "one-stop" investor service intended to replicate similar services in Singapore and Vietnam. This has yet to gain momentum.

More successful is Sheikh Hasina's digital push. With her son, a US-educated tech expert, as a key adviser, the program has introduced generous tax breaks for the information and communications technology sector; and a sweeping scheme to build 12 high-tech parks across the country.

Bangladesh's exports of software and IT services reached nearly $800 million in the year, till June 30, and are on track to exceed $1 billion this fiscal year.

There have been outstanding homegrown tech successes, such as the ride-sharing service Pathao, which received a $2 million investment from Indonesian unicorn Go-Jek, and mobile financial services group bKash, in which Alipay—an arm of China's Alibaba Group Holding—took a 20% stake in April.

What about pharmaceuticals?

Bangladesh is hoping to challenge India in pharmaceuticals, too. With its "least developed country" status, the country has enjoyed a waiver on drug patents.

This has fueled intensifying competition between India and Bangladesh in the field of generic and bulk drugs. Among local star performers are Incepta Pharmaceuticals, Bangladesh's second-largest generics maker, which exports to about 60 countries, and Popular Pharmaceuticals, which is eyeing an eventual listing.

One of Bangladesh's competitive disadvantages is its poor infrastructure, and the country has turned to China for help.

Under its Belt and Road Initiative, China has financed various megaprojects in Bangladesh, including most of the nearly $4 billion Padma Bridge rail link, which will connect the country's southwest with the northern and eastern regions. In all, China has committed $38 billion in loans, aid, and other assistance for Bangladesh.

China's heavy infrastructure investment has drawn criticism of its "debt diplomacy" in other countries, including Pakistan and Sri Lanka. However, local economists dismiss such concerns.

Chinese investors also bought 25% of the Dhaka Stock Exchange in 2018, and Bangladesh is now the second-largest importer of Chinese military hardware after Pakistan.

While some may question so much investment from Beijing, Sheikh Hasina said it is simply a fact that China is set to play a bigger role in the region.

Bitter political rivalry

Behind the impressive numbers and bold ambitions, however, are daunting hurdles ranging from structural problems to deep political divisions, which have come to the fore ahead of national elections on December 30.

Bangladeshi politics have been dominated for years by the bitter rivalry between Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia. Both women have been in and out of power—and prison—over the past three decades.

Khaleda Zia, who chairs the opposition BNP, is in jail on corruption charges that she says are false.

Since 1981, Sheikh Hasina has led the ruling Awami League, founded by her father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—the country's first president—who was killed by army personnel along with most of his family in 1975.

The party enjoyed strong support in some past elections. However, opposition activists and human rights groups have voiced concern about potential polling fraud and intimidation tactics.

After two consecutive five-year terms for the ruling party, analysts point to a palpable "anti-incumbency" sentiment among some voters. Yet from an economic standpoint, many agree that a ruling party victory would support further development.

Business seems largely on the ruling party's side—if only for stability's sake.

#Bangladeshis Must Choose ‘Lesser of Two Evils’ in Election

Bangladeshi voters will decide in parliamentary elections on Sunday whether to punish the governing party for worsening human rights conditions or reward it for overseeing a booming economy.During Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s two terms, the economy and social development have improved, according to most measures. But as she has tightened her grip on power, fundamental rights have been eroded.

Now the 71-year-old leader is seeking her third consecutive term on Sunday. In defending her record, Mrs. Hasina questioned the very definition of human rights.

“If I can provide food, jobs and health care, that is human rights,” she said this month in an interview with The New York Times. She vowed, if re-elected, to deliver 10 percent annual growth, up from the current 7.8 percent, and eliminate extreme poverty while continuing to strengthen welfare programs.

“What the opposition is saying, or civil society or your N.G.O.’s — I don’t bother with that,” she said of nongovernmental organizations and her critics. “I know my country, and I know how to develop my country. My biggest challenge is that no one is left behind.”

Local activists, political rivals and international rights organizations accuse Mrs. Hasina of co-opting state institutions like the judiciary and the police. Some Bangladeshis have been punished after speaking against the government, and a new law on digital security gives the police sweeping powers to monitor people’s activity online and arrest critics without warrants. There are fears she will become even more heavy-handed should she win a new term.

Mrs. Hasina and her Awami League are pitted against the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party. The country has vacillated between the two parties since the advent of democracy in 1991, when military rule ended.

But as the election approached, the government’s critics faced arrest and other forms of repression, a crackdown on dissent that a Human Rights Watch report this month described as “a climate of fear extending from prominent voices in society to ordinary citizens.”

Mrs. Hasina dismissed such criticism from local and international organizations.

“They are trying to please their donors and exaggerating,” she said, to get more funding.

Among the Bangladeshis who have been in officials’ sights is the photographer Shahidul Alam, who was jailed for months after being arrested in August for describing police violence against student protesters in a Facebook post and an interview with Al Jazeera.

“He was doing propaganda against the government and instigating people to violence,” Mrs. Hasina said of Mr. Alam, who has been freed on bail but could still face prison time.

Voters complain this election gives them few real choices. The opposition coalition is dominated by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party but encompasses some two dozen parties bound by little other than their desire to check the prime minister’s hold on power.

It is unclear which candidate the opposition would vote in as prime minister should it clinch a majority of the 300 seats up for grabs in the election.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s own track record is marred. Even its secretary general, Mirza Fakhul Islam Alamgir, acknowledged in an interview this month that human rights violations and corruption flourished under his party in the past, with extrajudicial killings and disappearances used as governance tools.

But Mr. Alamgir and his allies say that violations under the B.N.P. government were limited and that, given another chance, they would govern well.

Some voters who are satisfied with the economic development under Mrs. Hasina’s leadership may still vote for the B.N.P., not because they think the party has a greater affinity for human rights, but because they hope to salvage democracy, they say, by providing a check on the governing party in Parliament.

“We are choosing the lesser of two evils in our politics,” said Iftekharuzzaman, who goes by one name and is the executive director of the Bangladesh arm of Transparency International, a corruption watchdog.

“All government institutions have a stake in the elections now; they have been politicized strongly,” he said, adding that if Mrs. Hasina “wins a third term, she will increase her authoritarianism, her hold over the state.”

In Bangladesh’s short democratic history, Mrs. Hasina is the first prime minister to win two consecutive terms — partly because the opposition boycotted the last election in 2014, hoping to weaken her. But the boycott meant that Mrs. Hasina’s tenure has gone largely unchecked, creating the very political condition the opposition is now protesting.“The only silver lining one can see out of this mess is a Parliament with a significant opposition to provide some checks and balances,” Mr. Iftekharuzzaman said.

He and Human Rights Watch say that the governing party has undermined an open campaigning process, with the police intimidating opposition candidates and protesters, imprisoning politicians for several days under false charges and tearing down their posters.

The B.N.P. said this month that 10 of its candidates are in prison and 6,000 party loyalists have been arrested.

“If we have a multiparty system, a Parliament that works and a government without absolute power, then this election may be worth the intimidation,” said Kamal Hossain, the head of the opposition coalition. He had previously been allied with Mrs. Hasina.Independent observers say that antipathy toward incumbents is strong and that it is hard to determine whether Mrs. Hasina will win on Sunday. But the opposition is plagued by bitter infighting, and the manifestoes of the B.N.P. and the Awami League are nearly identical, promising vague paths to continued economic growth and better welfare programs.Mrs. Hasina said in her interview that the right to criticize the government freely is only a concern of the urbanized elites. She says her government has delivered on what rural Bangladeshis are most concerned with: getting food on the table, medical care and jobs.

Per capita income has increased by nearly 150 percent, while the share of the population living in extreme poverty has shrunk to about 9 percent from 19 percent, according to the World Bank.

Electricity generation has also increased drastically under Mrs. Hasina’s rule, helping to boost factory production and spreading out to homes in rural areas. The rates of maternal mortality and illiteracy have also declined.

Sultana Kamal, a Bangladeshi activist who was once close to Mrs. Hasina but has become increasingly wary of her, said a win by the current government would be seen as an indifference by voters to rights concerns.

“If Awami League returns, they will say, ‘The critics are criticizing us, but we returned to power on the people’s vote. The people don’t care about extrajudicial killings, human rights or corruption,’” she said.Bangladesh’s telecoms regulator has ordered mobile operators to shut down high-speed mobile internet services until midnight on Sunday, the day of a national election. Activists are worried that the shut down will prevent election monitors from sharing information about any irregularities at polling stations and alerting the public. For Rashed Khan, a student who moved to Dhaka from a farming village to attend college, resentment of the crackdown on freedom of expression and assembly is not limited to city-dwellers, as the prime minister says.

“I am from a village,” Mr. Khan said. “Village politics are important; they want to be able to speak their minds.”

Mr. Khan helped lead huge student protests this year that paralyzed the streets of Dhaka, the capital. After criticizing the government in a Facebook post, Mr. Khan was detained for two months, and he says he was beaten severely in custody.

Like other activists, Mr. Khan says democratic ideals cannot be sacrificed for economic growth.

“Why doesn’t the government want our opinion, our input?” asked Mr. Khan. “If we have no rights to criticize the government, this development doesn’t matter.”

#PashtunTahaffuzMovement #Pakistan - A praetorian state?

Zahid Hussain

December 12, 2018.

IT is not unusual in Pakistan for the military’s spokesman to opine on everything from security to foreign and domestic affairs. His press talks are given live TV coverage and his remarks make newspaper headlines. After a brief respite, the ISPR chief spoke again last week. And, sure enough, it covered a range of topics.

DG ISPR Maj Gen Asif Ghafoor was pleased with the economy’s “revival” and the government’s overall performance. While calling for a political solution to the Afghan crisis, he wanted the American forces to stay in Afghanistan. He warned the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) against crossing a “red line”. But, more importantly, the good general had some piece of advice for the media: show only ‘progress’ over the next six months. Is there anything left?

Indeed, the general was presenting not his personal but his institution’s thinking on those issues. But should the military spokesman be holding forth on policy matters that do not come under his domain? Should he be commenting on the government’s performance and opining on political affairs? Does he need to tell the media what to portray?

The civil-military imbalance has remained a major source of political instability.

It also raises the question of whether there exists an elected civilian government or if this is a praetorian state. Such statements by the military spokesman not only fuel confusion, but also undermine civilian institutions. The extensive media coverage given to his remarks, which often takes precedence over even those of top civilian leaders, is itself a statement.

Is it hard to understand the obligation of the military spokesman to adopt such high personal profile? The ISPR is expected to confine itself to security and other issues related to military matters. But this military organisation seems to have expanded its role hugely over the past few years — getting directly involved in matters that must not fall under its sphere.

Despite the military’s predominance, ISPR chiefs tended to maintain at least some semblance of balance and avoided being engaged in political controversies. But that seems to have gone awry. One clear example is the latest press conference that dealt with domestic political and foreign policies. It is not that the military leadership has not been involved in those matters, yet one does not expect the ISPR to be defining state policy.

Maj Gen Ghafoor maintains that, being a national institution, the military is not linked to any party or person. It was apparently in response to the prime minister’s statement that the military stood behind his government. Should it be seen as a rebuff to the prime minister or simply a statement of fact? There may not be any inference, but the clarification was not required.

It is not the first time that the DG ISPR has spoken about Pakistan’s Afghan policy. But his latest statement on the Afghan reconciliation process raises some serious questions. More importantly, it is the job of the foreign office to explain Pakistan’s foreign policy.

Maj Gen Ghafoor’s statement that the American forces should not pull out from the war-torn country was not prudent at a time when the Afghan Taliban is engaged in direct negotiations with the US. One of the insurgents’ demands is that of the timeframe for the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan. It is better to leave any policy announcement to the relevant civilian forums. Such statements undercut civilian authority and fuel confusion.

His remarks on the PTM, too, have got the institution engaged in unnecessary political controversy. It is a political issue and should be left to the civilian government to deal with. Such warnings could only ignite the situation. Surely there has been provocation from some elements within the movement, but generally the PTM’s supporters have remained peaceful. The military’s involvement in the matter could only provide ammunition to vested interests. We must learn some lessons from our experience in Balochistan. There is always a political solution to popular discontent. Outside powers can only fish in troubled water.

The DG ISPR’s advice to the media seems quite interesting. What the good general may not understand is that journalism is the act of bringing information and opinion into the public arena. It provides a platform for discussion across a range of political, social and development issues. Only when the media is free to monitor, investigate and criticise the state’s policies and actions can good governance take hold.

Free, pluralistic and independent news media contributes to social, economic and political development. The job of the media is to provide credible information representing a plurality of opinions, facts and ideas. But, unfortunately, there is now a move to stifle freedom of expression and plurality of views in the name of national security. This is extremely dangerous for the political and social cohesion of the country. The ISPR’s job should be to provide information, not to try to impose a particular narrative.

A narrow-minded approach and suppression of press freedom intensifies polarisation among the media, as is being witnessed today. Surely the media, too, must show responsibility and be objective, but any pressure to toe certain lines is not going to help. In this age of communication, facts on the ground cannot be glossed over. The paranoia over so-called hybrid war has become a major factor in the move to control the media.

The civil-military imbalance has remained a major source of political instability hampering the democratic process. Despite three democratic transitions, the space for the military establishment has not diminished. Indeed, the PTI government has moved cautiously, trying to maintain good working relations with the generals.

Prime Minister Imran Khan is right in saying that the military is behind him, and that has given the civilian government some space to breathe. It is imperative that this space be maintained for the smooth functioning of the system and to dispel concerns of the rise of a praetorian state.

2018: A year of media suppression and rights abuses in #Pakistan

By Rabia Mehmood

Over the past year, there was a noticeable increase in attacks on freedom of expression and human rights in Pakistan.

"Sneaky", "sinister" and "Orwellian" are just some of the words Pakistani journalists and human rights defenders used to describe the censorship and growing clampdown on dissent, mainstream andsocial media in their country over the past year.

Although previous Pakistani governments also put pressure on civil society and the media, this year, many Pakistanis working in these fields I talked to felt that direct and indirect repression has increased significantly.

Attacks on the media

As we were wrapping up 2018, there were a number of incidents that solidified the perception that the situation in the country has really gotten worse.

In early December, the Pakistani authorities blocked the website of Voice of America's Pashto language radio service.

Then on December 8, a police case was filed against dozens of people in the aftermath of a rally organised by the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (Pashtun Protection Movement - PTM), which campaigns for Pashtun rights. Among them were two journalists Sailaab Mehsud, affiliated with Dawn newspaper and Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty's Mashaal Radio, and Zafar Wazir of the local channel Khyber TV, who had been covering the rally.

On December 14, Pakistan's electronic media regulatory authority (PEMRA) issued an advisory note calling on media outlets not to report excessively on topics such as violence, kidnapping, sexual abuse, terrorism and natural disasters.

This document came after a similar one was issued in advance of the July parliamentary elections, which called on the media not to air "derogatory and malicious content" against the judiciary and the army. These regulatory letters purportedly aim to build a "positive image" of the country and address the "negative perception" of Pakistan globally, but many see them as a form of pressure on the media.

Then on December 15, Jang Group, the country's leading media house, fired hundreds of staffers en masse, closing down a number of its outlets.

Over the past year, a number of media organisations have had to downsize or close down due to declining advertising revenue or other financial constraints. Journalists I have talked to believe that this is a tactic to control the media and impose more "friendly" reporting on the authorities.

They also say that printing presses have been pressured to stop from publishing certain newspapers, cable operators have been asked to cease broadcasting certain channels and big businesses have been advised against putting up advertisements with certain media outlets.

The media have also been pressured to fire certain employees who have been too critical of the Pakistani establishment. This year, leading prime-time news show hosts Talat Hussain, Murtaza Solangi, Mateeullah Jan, and Nusrat Javed either quit or lost their jobs. What they have in common is that they all questioned the transparency of the July elections and openly criticised the jailing of the former PM Nawaz Sharif and his daughter Mariam Nawaz.

Journalists I talked to also shared their frustration with the increasing pressure and censorship in Pakistani newsrooms.

"It was ridiculous how we had to keep beeping off Nawaz Sharif when he would appear in court and during the election coverage. Election day was one of the worst days in my career as a producer in the newsroom, and I have seen the Musharraf era. We were not allowed to counter the official narrative of the authorities," a senior producer of a news bulletin of a prominent cable news network told me.

An editor of an English-language daily complained that a "screening process" was set up in his newsroom under the explicit directions of the publisher which resulted in everyday interference and forced removal of editorials and op-eds.

Pressure on civil society

In addition to an intensifying clampdown on the media and the resulting self-censorship, the authorities are now pushing hard to further suppress the civic space and impose the official narrative on the human rights situation in the country after the July election.

In 2018, the authorities escalated pressure on human rights defenders and activists peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression. They faced arrests, disappearances, accusations of treason, and violent threats from hardliner groups. The government has also stepped up filing complaints with social media companies against its online critics.

Recently, Minister of Information Fawad Chaudhry admitted that the authorities want to regulate social media. Over the past several months, a number of human rights defenders and activists have received emails from Twitter that their tweets violate the country's law; some accounts have even been suspended.

There have also been a number of human rights defenders, journalists and members of the legal profession who have either had to go into hiding or move to another country. Journalist Taha Siddiqui, for example, had to leave with his immediate family after narrowly escaping an abduction attempt.

The current government also continued the campaign the previous one started against non-governmental organisations (NGOs). As a result, this year some 18 international NGOs were forced to discontinue operations in the country, including Action Aid and Plan International.

Another prominent target of the Pakistani authorities' assault on civil society this year was the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement.

Many of its members, including two MPs, Mohsin Dawar and Ali Wazir, are facing police cases for taking part in rallies and corner meetings of the PTM.

In July, Hayat Preghal, a Pashtun human rights defender, was detained for a few days. He later faced charges of "anti-state" online expression via social media for his posts in support of PTM.

Preghal, who worked as a pharmacist in the United Arab Emirates, was in Pakistan on leave. Following the court hearing, his name was put on a no-fly list and as a result, Preghal, who is the primary breadwinner of his family, lost his job. He is yet another victim of what appears to be a campaign of targeted economic pressure against political dissidents and human rights activists.

Over the summer, Wrranga Lunri, a Pashtun women's rights advocate and supporter of PTM, also faced an intimidation campaign and had to relocate from her hometown in Balochistan. She was targeted for being a woman and an organiser, speaking out in public about her cause.

These are just a few of many examples of people who have fallen victim to the increasing intolerance for freedom of speech and human rights activism in Pakistan.

It is clear that this year the Pakistani authorities not only failed to abide by their constitutional and international commitments to ensure respect for rights and freedoms, but they actually actively engaged in campaigns of intimidation and censorship.

Unfortunately, there is little evidence that 2019 would be any different in this regard.

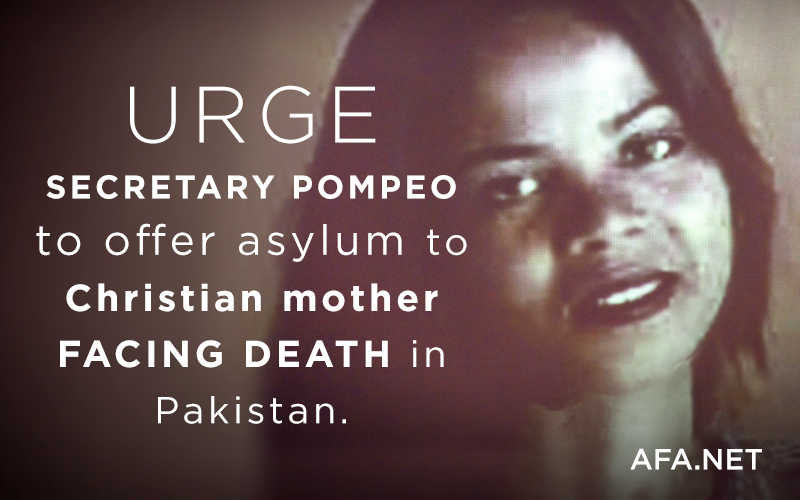

Scottish Politicians Press Theresa May to Grant Asia Bibi Asylum

A Scottish frontbencher has slammed the British government for failing to uphold the democratic value of freedom of religion in what she called a "failure" to address the situation of a Pakistani Christian, Asia Bibi, and grant her asylum in the United Kingdom.

A plea by more than 30 Scottish National Party (SNP) MPs has been sent to the UK Prime Minister Theresa May. The officials called on PM May to let Asia Bibi — who faces the threat of "violent mobs calling for her execution" in Pakistan — come to Britain and claim asylum.

SNP MP Carol Monaghan and other signatories to the letter praised "Canada, Spain and France for their offers of asylum, and note that Germany and Italy have reportedly held talks with Pakistan on the issue".

However, Westminster under Theresa May's leadership has failed to do the same, the MPs argued.

"If we claim to champion freedom of religious expression as one of the UK's core values, then we must act to uphold it rather than hiding behind others in fear of a backlash," they said in the letter.

A Catholic herself, Monaghan, said that her party would "continue to work with other parliamentarians and human rights organisations in pressing the UK government to take the right course of action."

Earlier in November, a group of politicians and campaigners have written to UK Foreign Minister Jeremy Hunt, urging him to grant asylum to Asia Bibi.

Bibi's case made headlines across the world, attracting backers and violent protesters — mainly in Pakistan — who spoke out on the matter.

Bibi was put on death row for blasphemy in Pakistan almost ten years ago, following allegations by Muslim women she worked with that she insulted Prophet Mohammed. Bibi denied the claims but was jailed and sentenced to hang on November 11, 2010.

The mother of three was eventually set free, following years in jail, after the Pakistani Supreme Court overturned the conviction last month. Bibi has reportedly spent Christmas in hiding, remaining in a secret location.

https://sputniknews.com/europe/201812281071063566-scottish-politicians-asia-bibi/

My client’s death sentence for blasphemy was overturned. She still cannot leave Pakistan.

By Saif ul Malook

Saif ul Malook, a lawyer, represented Asia Bibi in the successful appeal of her blasphemy conviction. Mehreen Zahra-Malik, a former Reuters correspondent based in Islamabad, assisted in the preparation of this op-ed.Asia Bibi spent Christmas in a safe house in Islamabad, Pakistan. I hope that’s the last time my client, a Catholic, must spend the holiday unable to live and worship in freedom. Two months ago, a three-justice panel of the Pakistani Supreme Court overturned her 2010 conviction and death sentence for blaspheming the prophet Muhammad. Protests by religious hard-liners over the possibility that she would be allowed to leave Pakistan prompted the government to bar her, at least temporarily, from departing.

Prime Minister Imran Khan’s government appears determined to ensure the safety of Asia and her husband, Ashiq Masih, and the couple’s two daughters, until another country agrees to take them in. Canada is their most likely destination.

Asia was still in prison, not in the courtroom, when the decision was handed down on Oct. 31. Enraged protesters poured into the streets in several Pakistani cities. Police escorted me from the courthouse, and I spent three days in hiding, aided by friends in the diplomatic community, before I boarded a flight for the Netherlands still wearing my Pakistani lawyer’s uniform of a black suit and white shirt. I had insisted I wouldn’t leave without Asia, but my friends swore they would take good care of her. It was my life they feared for at that moment.My last meeting with Asia had taken place on Oct. 10 at the women’s prison in Multan, about 250 miles from my home in the eastern city of Lahore, where she had been incarcerated for the past five years. Contrary to reports of her terrible treatment in prison, Asia seemed to have found a quiet life of sisterhood with her guards, who allowed her a television set and more time outside her cell than usually granted to death-row inmates. The relatively benign treatment might have resulted from pressure by Western governments, but I sensed it was because the guards recognized Asia’s bravery and human spirit.

Asia is not a sophisticated person. She was born 47 years ago to a poor family in a dusty farming village in the Punjab province and never sat in a classroom for a single day of her life. But she was helped by her strong religious faith when she ran afoul of blasphemy laws often exploited by religious extremists and ordinary Pakistanis to settle personal scores.

She was working on a berry farm in June 2009 with several Muslim women when a dispute broke out because Asia had filled a jug of water for her co-workers. Like many Pakistani Muslims, the women refused to drink water from a utensil touched by a choorhi, a derogatory word for a Christian. Apparently incensed that a lowly Christian woman had argued with them, two of the women who later appeared as witnesses in the case said Asia had insulted Muhammad and the Koran. Local clerics began denouncing her. An enraged mob beat her and dragged her to a police station, saying she had confessed to blasphemy.Asia was sentenced to death by a district court in 2010. She had legal representation in name only, because competent lawyers often fear to take on blasphemy cases. At least 70 people , including defendants, lawyers and judges, have been killed by vigilantes or lynch mobs since blasphemy laws were strengthened in the 1980s under the military dictator Gen. Mohammed Zia ul-Haq. A lawyers group that offers free legal advice to complainants is known to pack courtrooms with clerics and raucous supporters who try to bully judges into handing out convictions.

In 2011, Salman Taseer, the prominent governor of Punjab and a critic of the blasphemy laws who had visited Asia in prison and promised to lobby for her pardon, was assassinated by one of his own bodyguards. A few months later, Shahbaz Bhatti, a Christian and a cabinet minister for minorities who had also spoken up for Asia, was murdered.

I took on Asia’s case in 2014. I’m a lawyer, and I do not want to see anyone falsely convicted of a crime, much less hanged for it. The Supreme Court granted a petition to appeal her case, and in 2015 the death sentence was suspended. In October, I was notified that the final appeal would be heard. The justices’ ruling for Asia, citing insufficient evidence, took great courage.I think I will have to stay away from Pakistan for at least two years before it will be safe to return. Until then, I will live with friends in the Netherlands or with my daughter in Britain. But I yearn to return home to continue defending victims of the blasphemy laws.

Asia had rarely ventured far from her village before being imprisoned, so beginning a new life in another country would be a challenge for her. But she has shown remarkable strength throughout this ordeal, and I am confident that she will succeed.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)