M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Monday, January 14, 2019

Opinion My Sister Is in a Saudi Prison. Will Mike Pompeo Stay Silent?

By Alia al-Hathloul

The United States secretary of state is visiting Riyadh — but political prisoners are not on his agenda.

When Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visits Saudi Arabia on Monday, he is expected to discuss Yemen, Iran and Syria and “seek an update on the status of the investigation into the death of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.”

I am struck by what is not included in Mr. Pompeo’s itinerary: the brave women activists of Saudi Arabia, who are being held in the kingdom’s prisons for seeking rights and dignity. Mr. Pompeo’s apathy is personal for me because one of the women detained, Loujain al-Hathloul, is my sister. She has worked relentlessly to earn Saudi women the right to drive.

Loujain al-Hathloul in 2014, when she took a widely-viewed video of herself as she drove from the United Arab Emirates to Saudi Arabia.CreditLoujain Al-Hathloul/Loujain al-Hathloul, via Associated Press

Image

I live in Brussels. On May 15, I got a message from my family that Loujain had been arrested at my parents’ house in Riyadh, where she was living. I was shocked and confused because the Saudi ban on women driving was about to be removed.

We could not find out why she was arrested and where she was being held. On May 19, the Saudi media accused her and the five other arrested women of being traitors. A government-aligned newspaper quoted sources predicting the women would get sentences of up to 20 years — or even the death penalty.

Loujain was first arrested in December 2014 after she tried to drive from the United Arab Emirates to Saudi Arabia. She was released after more than 70 days in prison and placed under a travel ban for several months.

In September 2017, the Saudi government announced that the ban on women driving was going to be removed the following June. Loujain received a call before the announcement from an official in the royal court forbidding her from commenting or talking about it on social media.

Loujain moved to the U.A.E. and enrolled into a master’s degree in applied sociological research at Sorbonne University’s Abu Dhabi campus. But in March she was pulled over by security officers while driving, put on a plane and transferred to a prison in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. She was released after a few days but banned from traveling outside the kingdom and warned not to use social media.

Then came her arrest in May. I hoped that Loujain would be released on June 24, the date for removing the ban on women driving. That glorious day arrived, and I was delighted to see Saudi women behind the wheel.

But Loujain was not released. I remained silent, hoping my silence might protect her. Around that time, I was struck by a dark trend emerging on social media in Saudi Arabia. Anyone who criticized or made a remark on anything related to Saudi Arabia was labeled a traitor. Saudi Arabia has never been a democracy, but it hadn’t been a police state either.

I kept my thoughts and my grief private. Between May and September, Loujain was held in solitary confinement. In brief phone calls that she was allowed to make she told us that she was being held in a hotel. “Are you at the Ritz-Carlton?” I asked. “I don’t have the Ritz status, but it is a hotel,” she laughed.

In mid-August, Loujain was transferred to Dhaban prison in Jeddah and my parents were allowed to visit her once a month. My parents saw that she was shaking uncontrollably, unable to hold her grip, to walk or sit normally. My strong, resilient sister blamed it on the air-conditioning and tried to assure my parents that she would be fine.

After the killing of Jamal Khashoggi in October, I read reports claiming that several people detained by the Saudi government at the Ritz-Carlton in Riyadh had been tortured.

I started getting phone calls and messages from friends and relatives asking if Loujain too had been tortured. I was shocked by the suggestion. I wondered how people could think a woman could be tortured in Saudi Arabia. I believed that social codes of the Saudi society would not allow it.

But by late November, several newspapers, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International reported that both male and female political and human rights activists in Saudi prisons had been tortured. Some reports mentioned sexual assaults.

My parents visited Loujain at the Dhaban prison in December. They asked her about the torture reports and she collapsed in tears. She said she had been tortured between May and August, when she was not allowed any visitors.

She said she had been held in solitary confinement, beaten, waterboarded, given electric shocks, sexually harassed and threatened with rape and murder. My parents then saw that her thighs were blackened by bruises.

Saud al-Qahtani, a top royal adviser, was present several times when Loujain was tortured, she said. Sometimes Mr. Qahtani laughed at her, sometimes he threatened to rape and kill her and throw her body into the sewage system. Along with six of his men, she said Mr. Qahtani tortured her all night during Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting.He forced Loujain to eat with them, even after sunrise. She asked them if they would keep eating all day during Ramadan. One of his men answered, “No one is above us, not even God.”

A delegation from the Saudi Human Rights Commission visited her after the publication of the reports about her torture. She told the delegation everything she had endured. She asked them if they would protect her. “We can’t,” the delegates replied.

A few weeks later, a public prosecutor visited her to record her testimony about torture. After the killing of Mr. Khashoggi, Saudi Arabia argued that occasionally officials make mistakes and misuse their power. Yet we are still waiting for justice.

I would have preferred to write these words in Arabic, in a Saudi newspaper, but after her arrest the Saudi newspapers published her name, her photographs and labeled her a traitor. The same newspapers concealed the names and pictures of the men who could face the death penalty for the murder of Mr. Khashoggi.

Even today, I am torn about writing about Loujain, scared that speaking about her ordeal might harm her. But these long months and absence of hope have only increased my desperation to see the travel bans on my parents, who are in Saudi Arabia, revoked and to see my brave sister freed.

سعودی عرب میں خواتین کے حقوق: ’میں نے سعودی عرب میں اپنے خاندان کو کیوں چھوڑا؟‘

تصویر کے کاپی رائٹSALWA

تصویر کے کاپی رائٹSALWA

سعودی خاتون رہف محمد القنون کی ڈرامائی کہانی نے سعودی عرب میں خواتین کو درپیش پابندیوں کو ایک بار پر توجہ کا مرکز بنا دیا ہے۔

18 سالہ رہف محمد القنون نے گذشتہ ہفتے اپنے آپ کو ہوٹل کے ایک کمرے میں بند کرنے اور اپنے آبائی وطن واپس جانے سے بین الاقوامی توجہ حاصل کی تھی۔

انھوں نے سعودی عرب میں اپنے خاندان سے راہ فرار اختیار کی تھی، اور ٹوئٹر پر شروع کی جانے والی مہم کے بعد انھیں کینیڈا میں پناہ مل گئی۔

سعودی عرب میں خواتین کے حقوق کے بارے میں بحث تاحال جاری ہے، سعودی عرب چھوڑ کر کینیڈا آباد ہونے والی ایک اور نوجوان خاتون نے اپنی کہانی بی بی سی کو بتائی ہے۔

18 ماہ قبل 24 سالہ سلویٰ اپنی 19 سالہ بہن کے ہمراہ بھاگ گئی تھیں اور اب وہ کینیڈا کے شہر مونٹریال میں رہتی ہیں۔ ان کی کہانی انھی کی زبانی پیش کی جا رہی ہے۔

تیاری

ہم وہاں سے بھاگنے کی تیاری تقریبا چھ سال سے کر رہے ہیں لیکن اس کے لیے ہمیں پاسپورٹ اور قومی شناختی کارڈ کی ضرورت تھی۔

اس کے لیے ہمیں اپنے سرپرست کی رضامندی درکار تھی۔ (سعودی عرب میں خواتین کو بہت سے کاموں کے لیے خاندان کے کسی مرد کی اجازت کی ضرورت ہوتی ہے۔)

خوش قسمتی سے میرے پاس قومی شناختی کارڈ تھا کیونکہ میرے خاندان نے مجھے یہ بنوا دیا تھا جب میں یونیورسٹی میں پڑھ رہی تھی۔

میرے پاس پاسپورٹ بھی تھا کیونکہ مجھے دو سال قبل انگریزی زبان کا ایک امتحان دینے کے لیے اس کی ضرورت تھی۔

لیکن میرے خاندان نے یہ مجھ سے لے لیا تھا۔ اب مجھے یہ کسی طرح واپس لینا تھا۔

یہ بھی پڑھیں!

میں نے اپنے بھائی کے گھر کی چابیاں چرائیں اور پھر ان ایک دکان سے ان جیسی چابیاں بنوا لیں۔ میں ان کی اجازت کے بغیر گھر سے باہر نہیں جا سکتی تھی، لیکن میں نے اس وقت ایسا کیا جب وہ سو رہے تھے۔

یہ بہت خطرہ مول لینے والی بات تھی کیونکہ اگر میں پکڑی جاتی تو وہ مجھے نقصان پہنچا سکتے تھے۔

جب مجھے چابیاں مل گئیں تو میں اپنا اور اپنی بہن کا پاسپورٹ حاصل کرنے میں کامیاب ہوگئی، اور میں نے اپنے والد کا فون بھی اٹھا لیا جب وہ سو رہے تھے۔

اس کا استعمال کرتے ہوئے میں نے وزارت داخلہ کی ویب سائٹ پر ان کے اکاؤنٹ سے لاگ ان کیا اور ان کا فون نمبر اپنے نمبر سے تبدیل کردیا۔

میں نے ان کا اکاؤنٹ استعمال کرتے ہوئے اپنا اور اپنی بہن کے لیے ملک چھوڑنے کی رضامندی بھی حاصل کر لی۔

تصویر کے کاپی رائٹGETTY IMAGES

تصویر کے کاپی رائٹGETTY IMAGESفرار

ہم رات کو نکلے جب سب سو رہے تھے۔ یہ بہت، بہت دباؤ والی کیفیت تھی۔

ہم ڈرائیونگ نہیں کر سکتے تھے لہذا ہم نے ٹیلسی بلوائی۔ خوش قسمتی سے سعودی عرب میں تقریبا تمام ٹیکسی ڈرائیورز غیرملکی ہیں لہذا انھوں نے ہمارے اکیلے سفر کرنے کو حیران کن نہ سمجھا۔

ہم ریاض کے قریب شاہ خالد بین القوامی ہوائی اڈے کی جانب جا رہے تھے۔ اگر کسی کو اندازہ ہو جاتا کہ ہم کیا کرنے جا رہے ہیں تو ہمیں مارا جا سکتا تھا۔

اپنی تعلیم کے آخری سال سے میں ایک ہسپتال میں کام کر رہی تھی اور میں نے اتنی رقم جمع کر لی تھی کہ ہوائی جہاز کے ٹکٹ اور جرمنی کا ٹرازٹ ویزہ حاصل کر سکوں۔ میرے پاس بے روزگاری الاؤنس کی رقم بھی تھی جو میں نے بچا کر رکھی ہوئی تھی۔

میں اپنی بہن کے ہمراہ جرمنی کے لیے پرواز پکڑنے میں کامیاب ہوگئی۔یہ پہلا موقع تھا کہ میں جہاز میں بیٹھی تھی اور یہ بہت حیران کن تھا۔ میں نے خوشی محسوس کی، میں نے خوف محسوس کیا، میں نے سب کچھ محسوس کیا۔

جب میرے والد کو احساس ہوا کہ ہم گھر پر نہیں ہیں تو انھوں نے پولیس کو اطلاع کی لیکن اس وقت تک بہت دیر ہو چکی تھی۔

چونکہ میں وزارت داخلہ کی ویب سائٹ پر ان کے اکاؤنٹ میں ان کا فون نمبر تبدیل کر چکی تھی اس لیے جب انتظامیہ نے انھیں کال کرنے کی کوشش کی تو وہ دراصل مجھے کال کر رہے تھے۔

جب میں نے لینڈ لیا تو مجھے پولیس کی جانب سے پیغامات موصول ہوئے جو میرے والد کو بھیجے گئے تھے۔

آمد

سعودی عرب میں کوئی زندگی نہیں ہے۔ میں صرف یونیورسٹی جاتی اور پھر سارا دن گھر میں کرنے کے لیے کچھ نہیں ہوتا تھا۔

وہ مجھے مارتے تھے، اور مجھے بری باتیں بتاتے کہ مرد برتر ہوتے ہیں۔ مجھے زبردستی نماز پڑھائی اور رمضان میں روزے رکھوائے جاتے۔

جب میں جرمنی آئی تو میں نے پناہ کی درخواست دائر کرنے کے لیے وکیل تلاش کرنے کے لیے قانونی مدد حاصل کی۔ میں نے کچھ فارم بھرے اور انھیں اپنی کہانی سنائی۔

میں نے کینیڈا کا انتخاب کیا کیونکہ انسانی حقوق کے حوالے سے اس کی ساکھ بہت اچھی ہے۔ میں نے شامی مہاجرین کو یہاں دوبارہ آباد کرنے کی خبریں سنی تھیں اور فیصلہ کیا کہ میرے لیے یہی بہترین جگہ ہے۔ میری درخواست قبول ہوگئی، اور جب میں ٹورانٹو میں لینڈ ہوئی میں نے ہوائی اڈے پر کینیڈین جھنڈا دیکھا اور یہ کچھ حاصل کرنے لینے کا حیران کن احساس ہوا۔ .

تصویر کے کاپی رائٹGETTY IMAGES

تصویر کے کاپی رائٹGETTY IMAGES

آج میں مونٹریال میں اپنے بہن کے ہمراہ ہوں اور کوئی ذہنی دباؤ نہیں ہے۔ مجھ پر کام کے لیے زبردستی نہیں جاتی۔

سعودی عرب میں شاید زیادہ دولت ہوتی لیکن یہاں بہتر ہے کیونکہ میں جب بھی اپنے اپارٹمنٹ سے باہر جانا چاہتی ہوں جا سکتی ہوں۔ میں کسی کی رضا مندی کی ضرورت نہیں۔ میں باہر چلی جاتی ہوں۔

اس سے میں بہت، بہت خوش ہوتی ہوں۔ مجھے احساس ہوتا ہے کہ میں آزاد ہوں۔ میں جو کچھ بھی پہننا چاہوں پہن سکتی ہوں۔

مجھے یہاں خزاں کے رنگ اور برفباری پسند ہے۔ میں فرانسیسی زبان سیکھ رہی ہوں لیکن یہ بہت مشکل ہے! میں بائیسکل چلانا بھی سیکھ رہی ہوں اور میں تیراکی کرنا اور آئس سکیٹ بھی سیکھنے کی کوشش کر رہی ہوں۔

مجھے محسوس ہوتا ہے کہ میں اپنی زندگی میں واقعی کچھ کر رہی ہوں۔

میرا اپنے خاندان سے کوئی رابطہ نہیں ہے، لیکن میں سمجھتی ہوں کہ یہی میرے لیے اور ان کے لیے بہتر ہے۔ مجھے اب محسوس ہوتا ہے کہ یہی میرا گھر ہے۔ میں یہاں بہتر ہوں۔

https://www.bbc.com/urdu/world-46853272

#SHAME @ #Twitter - #Pakistan’s #Twitter Crackdown -

By Tehreem Azeem

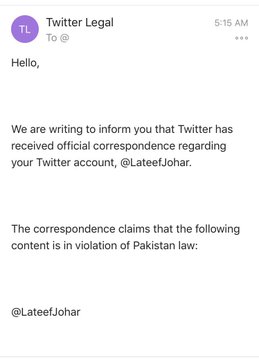

Twitter is sending emails to some journalists, human rights activists, and even foreigners to notify them of “official correspondence” it has received against particular tweets allegedly in violation of Pakistani law.

Abdul Qadeer Baloch, better known as Mama Qadeer, is a Baloch rights activist from Balochistan. He received an email from Twitter last Thursday, in which the micro blogging website informed him that it had received official correspondence regarding his Twitter account.

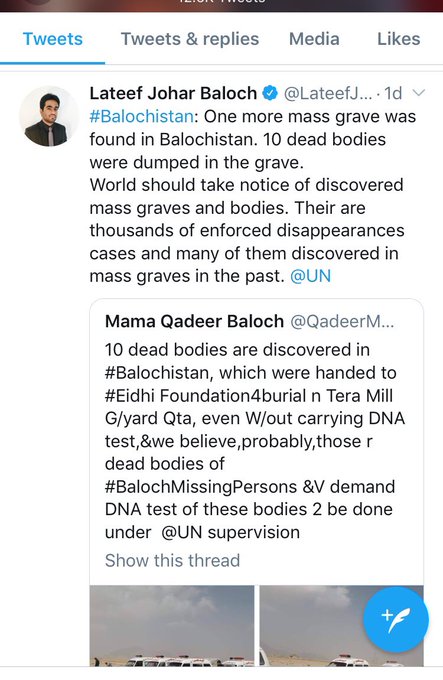

In the particular tweet referenced, Qadeer had written about 10 dead bodies that were found in the province. He writes in this tweet that those dead bodies were handed over to a nonprofit social welfare program for burial in the Tera Mill graveyard, Quetta without conducting any DNA tests.

In the particular tweet referenced, Qadeer had written about 10 dead bodies that were found in the province. He writes in this tweet that those dead bodies were handed over to a nonprofit social welfare program for burial in the Tera Mill graveyard, Quetta without conducting any DNA tests.

Qadeer, who is the founder of the International Voice for Baloch Missing Persons, believes that those were dead bodies of missing persons. In his tweet, he demanded DNA tests on the bodies under the supervision of United Nations.

10 dead bodies are discovered in #Balochistan, which were handed to #Eidhi Foundation4burial n Tera Mill G/yard Qta, even W/out carrying DNA test,&we believe,probably,those r dead bodies of #BalochMissingPersons &V demand DNA test of these bodies 2 be done under @UN supervision

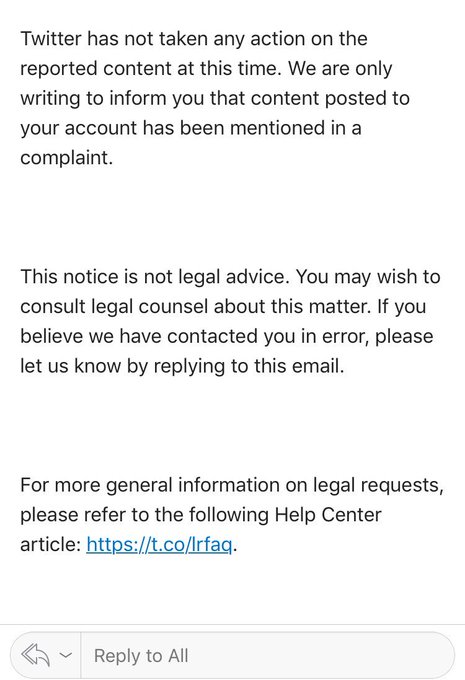

The email he received from Twitter mentions that the company was contacting him in response to official correspondence against his Twitter account and that one of his tweets was in violation of Pakistani law. The message, however, does not mention who filed the complaint and which law his tweet was allegedly violating.

He posted the screenshot of the email in a tweet and asked if championing for human rights was a crime, or if demanding a DNA test of unidentified corpses was a violation of Pakistani law.

I have received an email frm @Twitter where I'm informed that I have tweeted some content tht n violation of Pakistan law.

Does championing4HR is a crime?Or asking4DNA test of10 mutilated dead bodies under the supervision of @UN is violation of Pak law? @TwitterSupport #Twitter

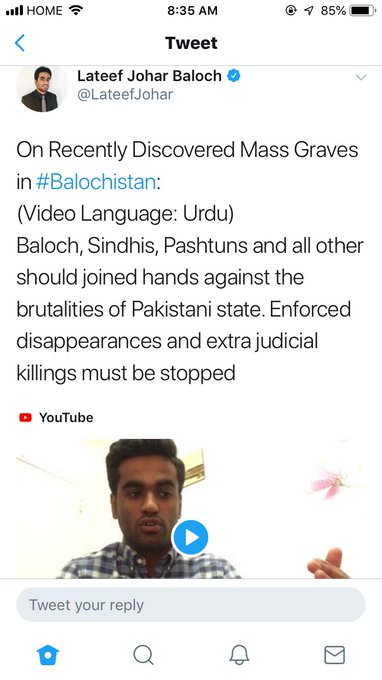

Another human rights activist from Balochistan, Lateef Johar Baloch, received the same email from Twitter for retweeting Qadeer’s tweet.

“What did I tweet? I questioned the ten bodies recovered in Balochistan buried without DNA tests. How did this break Pakistan’s laws? Is there something Pakistani authorities want to hide?” he asks in a tweet.

, @Twitter has warned me for violating #Pakistan’s laws and will shut down my account. What did I tweet? I questioned the ten bodies recovered in #Balochistan buried without DNA tests. How did this break Pakistan’s laws? Is there something Pakistani authorities want to hide?

In Balochistan thousands of civilians are missing. Locals believe that Pakistan’s military is behind these abductions. The actual number of missing persons is not known and mainstream media outlets don’t give much coverage to these abductions or the protests against the disappearances.

Earlier this month, senior journalist and anchorperson Mubashir Zaidi had received a similar email from Twitter for one of tweets regarding the murders of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa superintendent of police Tahir Dawar and former member of the National Assembly Ali Raza Abidi. Twitter notified him that the official correspondence mentioned that his tweet was in violation of Pakistani law.

I have received an email from @Twitter telling me that my below mentioned tweet is in violation of Pakistani law according to a complaint it received against me from Pakistan. No idea who is the complainant and how it violates Pakistani law?

Ali Raza Abidi, who was gunned down on December 25 outside his residence, was one of the strongest voices in the country. Hours after his brutal murder, Zaidi, in a tweet asked about the status of the investigations into the two murder cases.

What happened to the inquiry of Tahir Dawar? The cold blooded murder of #AliRazaAbidi will also remain unresolved like many before him

Dawar went missing from Islamabad on October 26 last year. In mid-November, pictures of a dead body found in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province started circulating on social media platforms. Later, government confirmed that those were pictures of Dawar.

Taha Siddiqui is another journalist from Pakistan who received a similar email from Twitter. Taha left Pakistan after a failed abduction attempt he blames on the powerful military over his frequent social media criticism. He is now settled in Paris, France and speaks openly against the Pakistani army on social media networks.

Twitter had sent a notice to columnist Gul Bukhari as well for her tweet in which she criticized the government’s lack of action against Tehreek-i-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) Chief Khadim Hussain Rizvi.

And the warning says the tweets were reported ‘officially’ for having violated Pakistani law. I’m wondering how criticising Govt for hypocrisy on corruption, or inaction against TLP violates the law. Shouldn’t @Twitter ask Govt to cite the law & explain how it’s violated first?

Other than these examples, several bloggers and foreigners have also received similar notices from Twitter. It is believed that the powerful military of the country is behind these complaints, which are increasing with every passing day.

According to a biannual report issued by Twitter in December last year, Pakistani authorities reported 3,004 Twitter accounts to the microblogging website for alleged offenses like “spreading hate material” and “inciting violence” in the first six months of 2018.

Last year the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) had informed the Senate Standing Committee on Cabinet Secretariat that while Facebook, YouTube, and other social media platforms had complied with requests from the government to block objectionable content, Twitter was not obliging. The government threatened to block the platform, after which it seems that the company has given in.

Last year the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) had informed the Senate Standing Committee on Cabinet Secretariat that while Facebook, YouTube, and other social media platforms had complied with requests from the government to block objectionable content, Twitter was not obliging. The government threatened to block the platform, after which it seems that the company has given in.

Freedom of expression, which is already declining in Pakistan, seems to be shrinking in online spaces too. The internet is heavily monitored and censored in Pakistan. Facebook regularly removes pages and posts critical to the Pakistani government, its policies, army, and religion. YouTube has launched a local version for the country after it was kept banned for three years. It was done under the pretext of controversial blasphemy laws but now it seems that the country wants to shut down any voice that it finds offensive. Journalists and human rights activists are the main targets.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)