M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Friday, December 14, 2018

The Last Secret of the 1971 India-Pakistan War

By James Maclaren

In the weak December sunlight, the Indian Air Force Hawker Hunter began a second run to strike the heavily defended radar complex set atop the Sakesar Mountain in West Pakistan. Its pilot, Flight Lieutenant Gurdev Singh Rai, knew the terrain well. He had conducted the same bombing run the previous day, dodging the wall of anti-aircraft fire that rose like a curtain from the Pakistani ground forces deployed to protect the base. The 1971 war was only two days old and Rai was part of the enormous air offensive that would decimate its Pakistan Air Force opponents and cripple Pakistan’s navy. That would allow Indian forces in the east of the country to strike deep into East Pakistan and force the capitulation of its forces, resulting in the creation of the new state of Bangladesh.

Unfortunately, Flight Lieutenant’s Rai’s short war was over. The hail of anti-aircraft fire from the ground batteries fatally wounded his aircraft. Rai crashed, and he was declared missing in action by his squadron later that day.

Two days later and 4,000 miles away, his younger sister Rajwant Kaur was sitting anxiously in the front room of her modest home in North London. She was watching the BBC’s evening news coverage of the war and alongside her was her husband and their landlord. Suddenly she bolted from her chair and went to the television pointing at the screen. “There,” she said excitedly. “Thank goodness, there is Gurdev.” There on the grainy screen was her brother, dirty and battered but safe, standing in a line of prisoners of war (POWs) guarded by Pakistani troops. Relief washed over her. He would be safe now; however the war went he would come home.

But Gurdev Rai never did come home. Rajwant waited days, then weeks, months, years, and finally decades for news, but she has never seen him or had official news of him since that grainy television picture.

How could this be? Gurdev was a POW and protected by international law. In theory when the conflict ended just a few days later with a decisive Indian victory, completed lists of prisoners should have been exchanged via the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). As POWs they would have been entitled to mail and fair treatment, and should have been repatriated as soon as possible under internationally monitored arrangements. The 90,000 Pakistani POWs were rapidly returned but the unknown fate of Flight Lieutenant Rai is not an isolated case. When Pakistan produced its list of 635 POWs, 51 suspected Indian POWs from 1971 were not accounted for — leaving their families grieving confused and over time to a large extent forgotten. The earlier conflict between the two countries in 1965 had left three other personnel still unaccounted for, bringing the total missing to 54 men who served in all branches of the Indian Armed Services.

Suspicion that the men may still be alive and held captive by Pakistan continues. Over the years, reports of sightings of the men have emerged. Dr R.S. Suri, father of Major Ashok Suri, at first believed the army when they declared Major Suri as “Killed in action” in the 1971 war. Then in early December 1974 he received a smuggled note apparently from his son saying that he was well. The note had been carried by a released prisoner in Pakistan who claimed Major Suri was still being held in jail. To raise hope further, a second note from Major Suri arrived and was declared sufficiently authentic by the Indian Defense Ministry to have the officer’s official status changed from “killed in action” to “missing in action.”

Various other sightings of the missing men have taken place.

Major A.K. Ghosh was caught on camera by a Time newspaper reporter in late December 1971. A Pakistan radio broadcast in early December 1971 reported that Flight Lieutenant L.M. Sasoon, shot down while on a bombing mission, had survived the wreckage of his Canberra aircraft and was in captivity. The young wife of Flight Lieutenant Ashok Balwant Dhavale received his wallet, which included her photograph, and his scarf intact, but despite these personal belongings there was no apparent sign of his body near his wrecked aircraft.

Wing Commander Hersern Singh Gill was by reports befriended by two imprisoned Pakistani officers jailed in Attock military prison in 1973-1974 for their role in plotting a military coup. Other reports suggest that up to 40 unaccounted for Indian prisoners were held in Attock Jail at that time.

A Sikh prisoner repatriated to India reported a meeting in 1983 with a Captain Kamal Bakshi, whom he had met while serving time in Multan Jail. Captain Bakshi’s sister is British and still lives in London.

As late as 2003, a Canadian human rights representative visiting Lahore Jail was called out to by prisoners claiming to be held from the 1971 conflict but was denied contact with them by his minders. Even more recently, in 2012, an Indian carpenter working in Oman reported he had been approached by a fellow Sikh who claimed to be Sepoy Jaspal Singh and said that he and four other Indian POWs had been held in Oman since 1975, in what would be one of the earliest cases of rendition.

Pakistan has always denied any knowledge of the men. In 1982, Zia-ul-Haq, the military dictator of Pakistan, visited India. In a surprise move, he agreed to allow some of the families to have consular access to prisons where it was suspected the majority of the 54 POWs were being held. Six of the families travelled to Pakistan, although the heavily controlled visit yielded no sign of their loved ones nor clues as to where they might be.

As the years have passed, the families’ faith in their own government’s actions in attempting to recover the men have been shaken. The Indian government seems unwilling to internationalize the issue.

In 2015 human rights lawyer Jas Uppal, who runs from the U.K. charity Justice Upheld, petitioned the Indian Supreme Court wanting the matter raised with the International Court of Justice as a matter concerning international law. As a result of her petition, the Court received an affidavit from the Indian Ministry of Defense in which it declared that it had no details regarding 54 missing defense personnel believed to be held captive as prisoners of wars (POWs) in Pakistan jails after the 1965 and 1971 wars.

Uppal has had the question of the missing POWs raised in the U.K. Parliament, bringing the attention of the U.K. government to the fact that two of the missing POWs have sisters who are British citizens. However, the Foreign Office declined to become involved, referring to the matter as a bilateral issue between India and Pakistan. Uppal does not consider that good enough.

“Two of the kin of the Indian POWs are British nationals who urgently need the support of their government to ascertain the fate of their kin,” she says. “The British authorities have good diplomatic ties to both India and Pakistan therefore Britain is the best placed to mediate in this situation.”

So far, her calls to elevate the case of the men has gone unheeded.

So, what happened to the missing 54 POWs? There is much evidence that these men survived the combat phase of operations and Pakistan has a history (which continues today) of conducting ex-judicial detention. Its jails hold detainees who fall into special categories of prisoner, determined by the nation’s powerful security apparatus rather than the courts. Many believe that the fear of prosecution by the new nation of Bangladesh for war crimes committed by members of the former Pakistan military meant Indian POWs were held for use as bargaining chips against such prosecution. Over time the prisoners became an embarrassment — possibly to both sides — as the turbulent diplomatic relationship between the two countries never produced the right time to reveal their existence.

This view may be supported by the decision of the Red Cross to keep its records of the Indo-Pak war of 1971 confidential until 2035. The reasons for this remain obscure but suggest that details of negotiations between the two countries are too sensitive to be made public. That’s only a short step from explaining away the missing 54 as simply collateral damage as the two nations struggle to live next to one another. It’s unlikely all of these men have survived nearly five decades in captivity but it’s quite possible that some did. If so, they continue to wait with diminishing hope that their government and international pressure will come to their assistance and allow them to live the last few years of their lives in a dignified manner.

The men have never faded from the memory of their families, who keep hoping to learn the truth of what happened to their loved ones following that short war. Numerous appeals for information and legal applications to both governments and the international community have led nowhere.

Sadly, for Rajwant Kaur, a serious car accident has left her confined to a wheelchair. Yet she still waits, patiently sustained by the hope that one day her brother will walk into the room where she lives alone in a North London suburb and they will be reunited.

Elsewhere, when Indians celebrate December 16 as “Vijay Divas” (Victory Day) the families to whom the 54 POWs never returned will have mixed and muted feelings as they wonder whether their loved ones remain hidden after all this time behind a Pakistani prison door.

Sherry raises questions on devaluation of rupee in Senate

PPP Parliamentary leader in Senate Sherry Rehman, speaking in the Senate raised five key questions pertaining to the recent rupee devaluation and Pakistan’s spiralling economy in her calling attention notice.The combined opposition then staged a walkout after the senator’s questions were not adequately answered in the absence of the finance minister.

Sherry Rehman pointed out, “It is rather troubling that the finance minister is readily available for media appearances and has answered more questions in talks shows and press conferences than he ever has in parliament”.

The senator then questioned the government on who is calling the shots on Pakistan’s economy, “If the prime minister did not know about such a huge devaluation and yet the Finance Minister did, then who is in charge and who will take responsibility? Entire livelihoods were wiped out in the crash while they were celebrating their first 100 days in government,” she said.

“If the precipitous devaluation was not part of any IMF precondition to bring the rupee down to non-artificial rate, then why was it done in such a disastrous freefall in two crashes? Either way why was the managed float not graduated down slowly?” asked the former senate opposition leader.

Rehman added, “If the current account deficit will be fixed by this adjustment via a more robust export sector why are all the exporters saying that the crash is too steep and the comparative impact on imports is too high to help our exports?”

The senator also reiterated the importance of transparency. She said, “When a country’s currency crashes so fast in one or two days, then there has to be an inquiry into who traded on the inside and made a fortune, while others lost their businesses and savings. The FIA should share its findings with parliament on which money changer or syndicate profited from the devaluation”.

“We are told the external account is under immense pressure but tell us if billions won’t be added to foreign debt as a result of the whopping exchange rate adjustment? It is the finance minister’s job to answer these five questions in parliament”, she concluded.

How Benazir Bhutto and personal tragedy influenced Theresa May's early years

Theresa May’s political career stands at the brink but what is driving her on is a strong sense of duty forged in her childhood

The anarchy engulfing her leadership, even before the confidence vote in her Conservative party, lies in stark contrast to her early years in the seaside town of Eastbourne.

She led a relatively quiet upbringing as the only child of a Church of England clergyman. In comparison to many of her Conservative colleagues Mrs May attended state schools rather than the expensive private institutions steeped in history many of her predecessors went to.

Gaining a degree from Oxford fitted more into the tradition of UK leaders, but her subject choice of geography was not the typical breeding grounds for a prime minister even if she then spent six years working for the Bank of England.The early 80’s were marked by tragedy when her father died in a car accident and her mother from multiple sclerosis. Aged 25 and finding her place in the world, she was now an orphan. Mrs May has previously commented she was sorry her parents never saw her elected as a Member of Parliament – but they didn’t even witness her role tenure as a Conservative councillor for the London borough of Merton from 1986 to 1994.

Helping her through the tragedy was her husband Phillip, who she married in 1980 at the age of 23 after meeting at Oxford University, and is often described as her “rock.” Mrs May had an eclectic group of friends whilst studying, including Sir Alan Duncan and Damien Green, who would later become ministers and close allies.

However, it was Benazir Bhutto, the future Pakistani prime minister, who was particularly influential when she introduced Mrs May to Phillip.

In her early parliamentary career, after being elected for the new constituency of Maidenhead in 1997, one her most notable roles was as the first female chairman of the Conservative’s. She famously urged the party to change, uttering the words: “You know what people call us? The Nasty Party.”

When David Cameron became prime minister in 2010, he immediately made Mrs May home secretary become the fourth women to hold one of the British great offices of state. Arguably her biggest test was the 2011 summer riots, when a London man was shot dead by police, sparking country-wide chaos that mirror the state of UK politics.

Comparisons are being made between Mrs May’s predicament and Malcom Turnbull, former Australian prime minister, who faced a leadership crisis earlier this year in his Liberal party. He survived the initial vote, but amid further pressure only ten days later he handed in his resignation. What will happen with Mrs May remains to be seen.

https://www.blogger.com/blogger.g?blogID=6906155786122195046#editor/target=post;postID=121421118326680383

Benazir Bhutto: The ‘Iron Lady’ of Pakistan

Muhammad Ziauddin

Eleven years is a long time. But it is still very difficult to accept that Benazir Bhutto is no more. She is missed, she is mourned and she is remembered with fond memories by many, including scribes like me who had the good fortune of observing her from very close quarters while covering her as she began her tumultuous political career that spanned over 30 eventful years and then also having had the misfortune of writing her obituary.

But much has happened since her assassination to turn her, at the national level, into a fading memory because the national party that she had left behind has in the intervening period turned into a provincial one in size and reach and today it is confined to the rural part of Sindh. Second, the uplifting political narrative that she and her father had used to rally political support of the downtrodden has meanwhile been assumed by other mainstream parties including PML-N and PTI, with the latter employing it more effectively. Third, General Zia’s legacy of Islamisation and Jihad has shrunk the political space for parties anchored to progressive ideologies.

The left-oriented slogan, “Land to the Landless”, proved irresistible to the peasants. The working class and labour movement quickly flocked to the party.

She challenged a ruthless military dictator, suffered for her daring, managed to revive a political party which had gone into doldrums, and made history by becoming the first woman to win the coveted office of Prime Minister of a Muslim country and that too, twice. But all this has turned into an intangible legacy; unlike that of the General Ayub era, which is remembered for the fast-paced industrialization, the military pacts he had entered into with the US and the Indus Basin Treaty that he signed with India. Her father is remembered for giving the nation the 1973 constitution and his legacy of nationalization.

Zia is remembered for Islamisation and Jihad. Nawaz would perhaps be remembered for the motorways he built. And Musharraf would probably be remembered for letting terrorism take a deadly hold on the nation. At 29, Benazir was locked in an acrimonious confrontation with a military dictator who had a rubber-stamp Supreme Court send her father to gallows on trumped-up murder charges; suffered a couple of years of solitary incarceration in Sukkur which sizzles in summer and a five-year long exile. Zulfikhar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) at 29 was already a government insider.

t was perhaps the ruthless persecution of PPP by General Zia ul Haq that sucked Benazir into Pakistan’s political cauldron. Still, she was 26 when she became co-chairperson of the Party. And by the time she eased Begum Nusrat Bhutto out of the Party office, Benazir was a mature lady of 34. Benazir did not automatically inherit her father’s political mantle. First, she was not the first of ZAB’s children. Second, she was a woman in an overly man’s world soaked in an obscurantist version of Islam.

When Zulfiqar Bhutto launched the PPP, he was more mature and experienced at 34, as he had already for a couple of years held the office of Secretary General of the ruling Convention Muslim League besides having held a number of portfolios in Ayub’s cabinet including that of the country’s foreign ministry. When ZAB returned home after attending Berkley, Oxford and Lincoln’s Inn, he was 27 and one of the most highly educated young barristers in the country. By the time Benazir went to Harvard and Oxford studying governance, philosophy, politics, and economics, she was not an exception.

Benazir had also needed, in view of the fact that it was now a unipolar world with the U.S. at the helm, to amend PPP’s anti-American stance.

There were many girls in the country with a similar upbringing. ZAB launched the PPP as the Vietnam War was winding down in the late 1960s and the world was being swept by left of- center winds. Western Europe and even the U.S. to some extent, had become social welfare states with public sector catering for the nations’ education, health, transport, communication, housing, energy, and water. Bhutto’s program directly targeted the country’s poverty-stricken masses. The left-oriented slogan, “Land to the Landless”, proved irresistible to the peasants. The working class and labour movement quickly flocked to the party.

Many other members of society who had felt stifled and repressed by the authoritarian regime also joined the new party. The party’s manifesto attracted the country’s numerous sectarian minorities. Eventually, the socialist-oriented catchphrase ‘Roti, Kapra aur Makan’ became a nationwide rallying-call for the Party. However, by the time Benazir returned home in 1986 to a memorable welcome, the world had undergone a qualitative change on the ideological front. Soviet Communism was breathing its last gasps. Europe and the U.S. were on their way to the era of less government. British Prime Minister Mrs.

Thatcher of the Conservative Party had forced the opposition to morph into New Labour, which ideologically seemed similar to the Conservatives if not identical. In Reagan’s U.S. social infrastructure carried a price tag. In Pakistan, nobody knew what had happened to the unencumbered billions that had come in by way of rent for our assistance to the U.S. in its war of attrition against the Soviets in Afghanistan. And by the time Zia died in an air crash in August 1988, our kitty had bottomed off forcing the then finance minister, late Mehbubul Haq to run to the IMF, for a paltry standby loan, which the fund agreed to provide but only to the winner of the 1988 elections.

So, the winner, Benazir led PPP, walked straight into the Washington Consensus that was opposed to the social welfare agenda of ZAB’s PPP. Benazir had also needed, in view of the fact that it was now a unipolar world with the U.S. at the helm, to amend PPP’s anti-American stance. She also needed to establish working relations with the country’s establishment that had bitterly persecuted the PPP all through Zia’s 11-year rule. The establishment suspected her credentials. Some even branded her as a security risk.

The former was roughly estimated to be about 33 percent and the rest was anti-Bhutto. But most of these anti-Bhutto votes were scattered over a number of right-wing political parties.

Here let me digress a little. The return of Benazir in 1986 from exile, had happened at about the time when the U.S. administration was distancing itself from President General Zia ul Haq because the latter was opposing the Geneva Accord talks, which had begun in 1985 between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. These Accords were finally signed in early 1989 between Benazir Bhutto’s Pakistan and Soviet-backed Najibullah’s Afghanistan with the U.S. and the Soviet Union standing in as guarantors.

Zia was perhaps opposed to Benazir’s return as well but the then Prime Minister Mohammad Khan Junejo who had started asserting his independence had facilitated her return, presumably on the advice of the U.S. Of course, there is no tangible evidence of money having been used in the 1988 elections. But the then ISI Chief General Hamid Gul according to his own public admission did put together the Islami Jamhoori Ittehad (or IJI), a conglomerate of almost all the right-wing parties of the country in September 1988 to stop Benazir Bhutto led PPP from winning the forthcoming November elections.

However, the PPP still managed to win the 1988 elections. But in the next elections called in October 1990, the establishment did not take any chances. According to another former ISI chief Asad Durrani’s admission, he had distributed millions of rupees among Pakistani politicians including many of those belonging to the PML and Jamaat-i-Islami in 1990 “on the instructions of the then army chief General Mirza Aslam Beg and late President Ghulam Ishaq Khan”.

Here one needs to remember that Benazir did not actually inherit the Party that ZAB had founded. It had been completely decimated by General Zia and his cronies by the time Benazir came of age and took over the chairperson’s office from Begum Nusrat Bhutto, who despite the destruction of the Party at the hands of Zia had succeeded in keeping its vote bank intact. ZAB had founded a left-of-center party which was more left than center. Benazir, on the other hand, when she died left behind a party which was more center than left.

It was Benazir who had selected the candidates and issued them tickets to contest the 2008 elections. Zardari was not even remotely connected with this selection process.

Throughout the three decades leading up to the turn of the century, the electorate in Pakistan was divided into a pro and anti-Bhutto vote. The former was roughly estimated to be about 33 percent and the rest was anti-Bhutto. But most of these anti-Bhutto votes were scattered over a number of right-wing political parties. Over the last two decades or so, the anti-Bhutto vote seems to have disappeared gradually. That is why no political party, even staunchly opposed to the PPP, tries to mobilize political support with anti- Bhutto rhetoric anymore. Most avoid criticizing the Bhuttos in public. It is not considered good politics.

That is another reason why perhaps the PPP is finding it increasingly difficult to attract voters using the name of Bhuttos. ZAB had subscribed to the Fabian philosophy that had fostered the idea of advancing the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort rather than by revolutionary overthrow. And Benazir, on the other hand, was inspired first by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s politics and later seems to have persuaded herself to subscribe to what was called the New Labour when the British Labour Party morphed into a caricature of Conservatives.

While trying to adjust their respective political aspirations to the ground realities in Pakistan both ZAB and BB had gradually become centrists attracting a large nation-wide crowd encompassing people belonging to right-of-center and left-of-center, as well as pure centrists. Most of these voters now seem to have gone over to the PML-N and the PTI because of the quality of governance of the PPP during the last ten years, five of which were at the center and an entire decade in the province of Sindh.

It was Benazir who had selected the candidates and issued them tickets to contest the 2008 elections. Zardari was not even remotely connected with this selection process. Had she been alive and led the election campaign perhaps she would have swept the polls hands down. However, her tragic assassination did not seem to have attracted enough sympathy votes. In fact, it lost many, because of the uncertainty that had engulfed the Party when Asif Ali Zardari took over after her assassination.

Benazir’s return from self-exile in 2007, like in 1986, was facilitated by the U.S. as like then differences had presumably cropped up between the U.S. administration and the then Pakistani military dictator, General Pervez Musharraf over how to go about restoring peace in Afghanistan. Benazir’s condition for returning home was removal of the constitutional bar against contesting for the third time for the office of the PM. The demand was rejected by Musharraf but he accepted her alternate demand that had asked for withdrawal of all cases of corruption instituted against her and her party leaders including her husband.

A National Reconciliation Ordinance (NRO) was promulgated by the President making way for return of both Benazir and Nawaz. An attempt was made to assassinate Benazir in Karachi on the very day that she returned from her self-exile which she escaped. But she could not survive the second attempt made in Rawalpindi on December 27, 2007. Like most high profile assassinations in this country, hers too seems likely to join the list of Pakistan’s blind murders like that of Liaquat Ali Khan and Murtaza Bhutto. Indeed, a decade is too long a period for leads, both hard and circumstantial, to have remained alive. Still, the hunt must continue.

پاکستان کو ’’خان کی جاگیر‘‘ کے طور پر نہیں چلایا جا سکتا،بلاول

بلاول بھٹو نے کہا ہے کہ عمران خان کو سمجھنا چاہئے کہ پاکستان کو ’’خان

کی جاگیر‘‘ کے طور پر نہیں چلایا جا سکتا۔شہباز کو چیئرمین پی اے سی بنانا خوش آئند ہے، ترجمان پی پی نے کہا کہ اپنے نفع نقصان کیلئے نہیں، جمہوریت کیلئےفیصلہ کیا،حکومت کےاپوزیشن لیڈر کوپبلک اکاؤنٹس کمیٹی کا چیئرمین مقرر کرنے پرآمادہ ہونےپر اپنے ردعمل میں چیئرمین پی پی پی بلاول بھٹو نے سماجی رابطوں کی ویب سائٹ پر جاری کردہ ایک پیغام میں کہا ہے کہ سمجھداری کا مظاہرہ خوش آئند ہے، بالآخر 4 ماہ بعد حکومت قائد حزب اختلاف کو پبلک اکاؤنٹس کمیٹی کا سربراہ نامزد کرنے پر آمادہ ہو گئی۔ انہوں نے کہا کہ یہ نامزدگی شفافیت اور احتساب کیلئے ضروری ہے اور اپوزیشن کو حکومت کو جوابدہ بناناچاہئے۔ بلاول نے یہ بھی کہا کہ حکومت نے کسی قانون سازی کے بغیر کئی ماہ ضائع کر دیئے ہیں۔ دوسری جانب، چیئرمین پاکستان پیپلز پارٹی بلاول بھٹو کے ترجمان سینیٹر مصطفیٰ نواز کھوکھر نے حکومت کی طرف سے قائد حزبِ اختلاف شہباز شریف

کو چیئرمین پبلک اکاؤنٹس کمیٹی بنانے پر آمادگی کا خیرمقدم کرتے ہوئے کہا ہے کہ آج ایک بار پھر چیئرمین پاکستان پیپلز پارٹی بلاول بھٹو کے اصولی مؤقف کی وجہ سے پارلیمنٹ سرخرو ہوئی، ہم اپنے سیاسی نفع نقصان کے لئے نہیں بلکہ جمہوریت اور اداروں کی بہتری کے لئے فیصلے کرتے ہیں۔

https://jang.com.pk/news/586881-topstory

The rich Balochistan and unfortunate Baloch

By: Abid Shaizad

Reko Diq is a less populated village of district Chaghe; which is a remote area of the rich province, Balochistan. According to the 1998 census the population of Chaghe District was 202,562, along with approximately 53,000 Afghan refugees. The population of Chagai District was estimated to be over 250,000 in 2005.

Reko Diq is famous because of its vast Gold, Copper and shell gas reserves and it is believed to be the world’s 5th largest gold deposit as 20 million tons and the copper, 12-13 million ton, which is estimated to be more than 3 trillion dollar of cost. Reko diq has got 50 kinds of minerals that are considered the high quality in the world. The mountain range of these reserves is spread on approximately 100 kilometers. The gold reserve is estimated to be 1276 ton. Acceding to experts’ estimation, if gold is extracted from Reko Diq as per day, it will be sufficient to do this for 50 years.

Misfortunately, the treasures of Reko Diq have been looting by the national and international muggers. This rich area of Reko Diq was given in lease to an Australian company which looted it and then handed over to other company for same reason. It is humiliating to know that the companies which are give this land on lease to extract gold, copper and other mineral that too without any accountability. They have been granted immunity from audit and check and balance in return of a little share to government of Pakistan in which Balochistan gets only 2 percent of its minerals, which reflects incapability of our leaders.

There are 9 mineral zones in Pakistan and 5 of them are found in Balochistan. So generous and tolerant is our Balochistan that it fulfills almost 90 percent of minerals of Pakistan; be it gold, gas, gypsum, chromites, marbles, coal, copper or the deep warm water sea port of Gwadar while its inhabitants are still silent on this regard; bearing hunger and thirst, accepting starvation and injustice, deprivation of basic facilities!

In addition, that, the district where reserves of Reko Diq are found, their people are suffering from different diseases and other health and fundamental rights. The federal and the helpless Balochistan governments have nothing to do with the people, their prosperity and the progress of Balochistan, but its minerals.

The federal and the provincial governments must take just measures to provide due rights of Balochistan in order to maintain peace and order and stability in the province and the country.

Published in The Balochistan Point on October 24, 2018

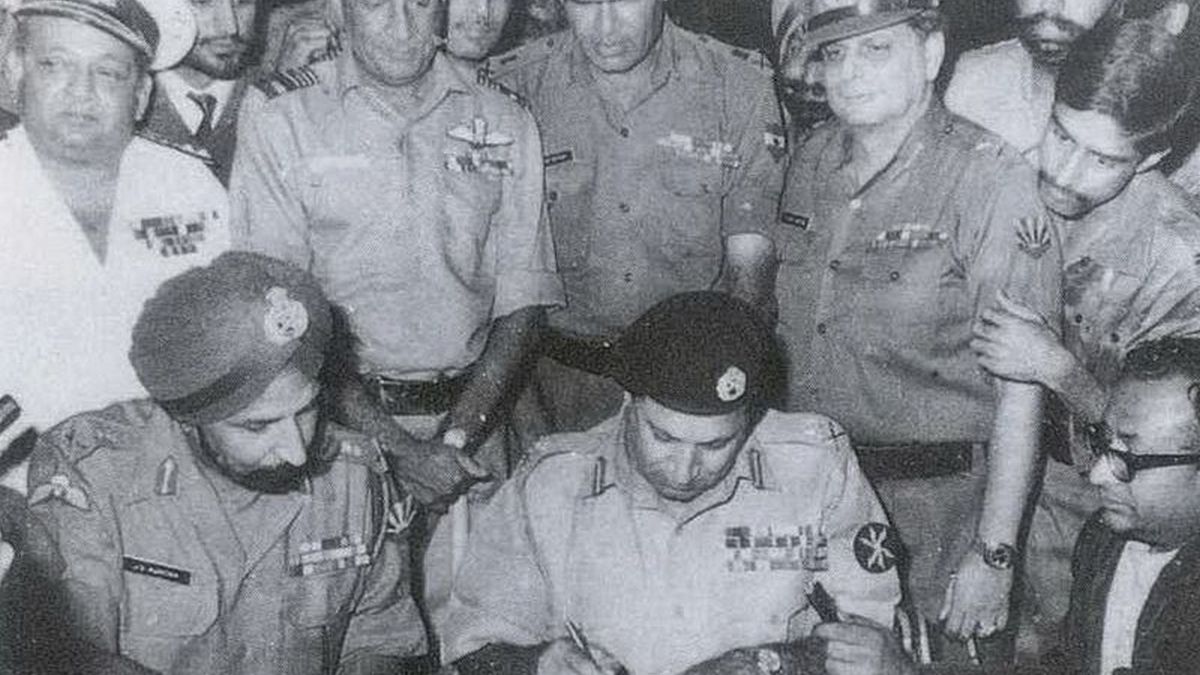

Dhaka & Pakistan’s psychological defeat: How Indian military commanders won 1971

LT GEN H S PANAG

Before 1971, our political and military leadership was inexperienced in waging a war at this scale to achieve absolute victory.

India’s absolute victory in 1971 to create Bangladesh was a result of some of our brilliant military commanders following a bold operational strategy to bring about the psychological collapse of the Pakistan army. This strategy was different from the rather conservative strategy originally conceived by the Army Headquarters.

Before 1971, our political and military leadership was relatively inexperienced in waging a war at this scale to achieve absolute victory. While the desirable political aim was to liberate East Pakistan and create Bangladesh, politically and militarily we were not very confident that this aim could be fully achieved.

The significance of Dhaka

There were two centres of gravity of East Pakistan – the Pakistan army and its critical vulnerability — Dacca (now Dhaka). So long as the Pakistan army remained a cohesive fighting force, and held on to Dhaka, the political aim could not be achieved. The new nation state would lack legitimacy and international or American intervention remained a possibility.

Our armed forces were not too sure of their capabilities as we had no experience of operations on this scale. The initial operational plan was a compromise. Dhaka was never formally defined as an objective. The directive given to the Eastern Command focused on capture of maximum territory, including the major towns and the port cities of Chittagong and Khulna, but shied away from declaring Dhaka as the military objective of the campaign.

Manoeuvre style of warfare

Culturally, our Army followed the attrition style of warfare, which relies on “force on force” to capture terrain objectives. This style literally seeks the enemy to attack. It was the influence of this culture that led us to consider that Dhaka was an “objective too far”. As per this approach, unless all other areas/towns, which were held by the enemy, were physically attacked and captured, we could not have reached Dhaka.

The manoeuvre style of warfare, instead, focuses on ‘defeat’, which lies in the psychological realm. It is empirical wisdom that barring exceptions, ‘defeat’ is a state of mind, a factor of ‘will’. When the conditions are created to bring about a psychological collapse, the enemy accepts defeat even if s/he has adequate resources to continue the fight.

Consequently, in this style, an all-out effort is made to threaten/capture/destroy the critical vulnerability of the enemy with sufficient residual combat potential. Only selected positions or ‘surfaces’ are attacked to create logistics corridors, and ‘gaps’ are exploited to reach the critical vulnerability. Once the critical vulnerability is threatened or captured, the forces, regardless of their strength, are rendered ineffective.

This was the reason why Dhaka had to be the operational-level objective. Without it, the psychological collapse of the enemy forces would not take place and victory would never be complete.

This was well understood by a handful of brilliant commanders and staff officers. Notable among them were the Chief of Staff Eastern Command Major General J.F. R. Jacob, Director General of Military Operations Major General Inderjit Singh Gill, GOC 4 Corps Lt. Gen. Sagat Singh, and Commander of 95 Mountain Brigade Brigadier H.S. Kler, operating under 101 Communication Zone.

These brilliant commanders never lost sight of Dhaka as the critical operational objective. When the seemingly insurmountable problems were pointed out to Lt. Gen. Sagat Singh by Lt. Gen J.S. Aurora, Singh said: “Leave it to me, I will take you to Dhaka”. Brigadier Kler used to give the example of the agile David striking at Goliath’s critical vulnerability – his forehead. On the eve of the war, he told his subordinates, “Do not take counsel of your fears, we will take this under-equipped brigade to Dhaka.”

Pakistan’s strategy

Pakistan’s Eastern Command also faced a dilemma due to paucity of resources. It correctly identified that Dhaka had to be defended. It was desirable that it was held in strength. Yet the vast territory ahead of Dhaka could not be given up.

The defensive strategy adopted by Pakistan Army was a compromise. Cantonments and major towns were to be developed as fortresses guarding the approaches to Dhaka. These fortresses were to push forward light forces right up to the international boundary (IB) to deny loss of territory. Depending upon the progress of the Indian offensive and the tactical situation, the formations were to conduct an orderly fighting withdrawal to wage a final battle around Dhaka.

India’s strategy

The “default strategy” that was adopted by the maverick commanders and the staff officers was perfect to a fault and ended up being adopted by the Army Headquarters midway through the war.

The political aim was to dismember Pakistan and create the new nation state of Bangladesh. The victory had to be absolute, leaving the international community with no option but to recognise the new state.

The operational strategy was to launch a land, air and sea campaign on multiple thrust lines from the west with 2 Corps, northwest with 33 Corps, north with 101 Communication Zone, east with 4 Corps and south with the Indian Navy. The aim was to threaten/capture the geostrategic and geopolitical centre of gravity – Dhaka – to bring about the psychological collapse of Pakistan’s Eastern Command, and in so doing establish tactical control over the entire territory of East Pakistan.

The preliminary operations, conducted all along the IB in November, “sucked” the enemy forces forward from Dhaka and the fortress towns. Once the war broke out, from 3 to 10 December, the Indian Army formations across the entire front left the ‘highways and took the byways’ to exploit the gaps and relentlessly attack selected positions from the rear to open logistics corridors. Risks were taken, opportunities were created and river obstacles were surmounted by 4 Corps using helicopter-borne forces and local resources. It was a Blitzkrieg on foot.

The enemy’s planned withdrawal to Dhaka became a disorderly retreat. The paradrop at Tangail on 11 December and link up by Brigadier H.S. Kler’s 95 Mountain Brigade from the north and the simultaneous “vertical envelopment” across the Meghna by Lt. Gen. Sagat Singh from the East opened the way to Dhaka. The leading elements, 2 Para and 95 Mountain Brigade, entered Dhaka early in the morning of 16 December, later followed by 57 Mountain Division of 4 Corps.

Bulk of the Pakistan army was still intact. The garrison at Dhaka far outnumbered the leading elements of 101 Communication Zone and 4 Corps threatening it. But such was the impact of the geostrategic and geopolitical centre of gravity being threatened that Pakistan’s Eastern Command psychologically collapsed. By the afternoon of 16 December, the surrender had taken place and history had been created!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)