M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Sunday, August 11, 2019

The IMF Repeats Old Mistakes in Its New Loan Program for Pakistan

By Shezad Lakhani

Prime Minister Imran Khan’s recent visit to Washington included a meeting with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), after the IMF Board formally approved a three-year $6 billion bailout program for Pakistan in mid-July. It was the country’s 13th loan in little more than 30 years. While repeated IMF conditional loans highlight inept economic management across successive governments in Islamabad, they also demonstrate how the IMF has largely failed at encouraging lasting reforms in Pakistan. The current program appears to once again be destined for failure.

The structural conditionalities the IMF sets out in the new loan agreement look eerily similar to the conditions set out when Pakistan’s last program began in 2013. The inclusion of the same policies less than three years after the “successful” completion of the previous program, underlines how little lasting impact the previous program had.

The new IMF program sets out a benchmark to audit the finances of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) and Pakistan Steel Mills, and gives the government more than a year to “triage” state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to determine which to privatize, liquidate, or maintain under state control. These points are included despite the fact that privatizing PIA and developing a reform plan for 30 SOEs were conditions in the previous program. While the IMF noted in October 2016 that significant preparatory work on SOEs had been conducted, rather than moving forward with the work already conducted the IMF is allowing the government to restart the process.

The new program also gives the government three months to prepare a comprehensive plan to address the financial losses in the electricity sector, generally referred to as “circular debt.” The government is being given additional time to come up with a plan, even though circular debt is an issue that has plagued every government in power since at least 2008, and was a core element of Pakistan’s last program.

The IMF has to include similar structural reforms in its new program because its approach results in governments in Islamabad taking steps that temporarily improve financial conditions. However, these measures are easily reversed once the loan program in concluded. The Fund continues to allow Pakistan to study, plan, and prepare for structural reforms, but as each loan program progresses, the immediate economic crisis dissipates, and political will wanes. In the end, the prepared policies are not implemented, leading to episodic rather than sustained economic improvements.

For instance, Pakistan had to implement policies to increase tax revenues in its announced budget and reduce electricity subsidies before the Board approved the loan agreement. Pakistan implemented similar policies before and during its previous program, but after the program ended and elections approached, it quickly reversed course by substantially increasing spending. This led to the crisis that the current government inherited.

While pushing for periodic electricity price increases, the previous two IMF programs were not able to remove political interference in setting of prices in the sector, which drives the over a decade-long circular debt problem. Similarly, while each program had benchmarks involving privatization, Pakistan has not privatized any major SOEs since the mid-2000s.

The previous conditional loan, like the current one, set out to improve the independence of the central bank, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). But while the previous government increased independence on paper, once the program ended then-Finance Minister Ishaq Dar still pressured the SBP to maintain a strong rupee, leading to a rapid loss of precious foreign exchange reserves.

The IMF’s tedious approach of advocating for reforms occurs as economic problems in Pakistan continue to get more serious. Pakistan’s general government debt increased from an already high level of 66.7 percent of GDP before its last program to 74.9 percent of GDP last year. Cumulative losses of SOEs have climbed from 3.5 percent of GDP to about 4.5 percent of GDP.

Most importantly, repeated economic crises and the failure to address core economic constraints has led to growth remaining far below potential, which is especially concerning since Pakistan has a large and growing working age population that lacks sufficient economic opportunities.

The frequency of IMF programs for Pakistan is the most telling sign of their failures. Unless the IMF changes strategies during the current bailout, it is likely that Pakistan will need a 14th program in the next several years.

Since the IMF has been constantly engaged with Pakistan, the lender would do well if programs were built on work done during the previous loan agreement rather than starting from scratch each time. While governments in Pakistan change, the fundamental work done to prepare for structural reforms can be used across programs.

The Fund could also potentially have more success by pushing for structural reforms, such as privatization or changes in governance, early in the program, when Islamabad is more desperate for IMF support, rather than settling for important but easily reversible steps.

#Pakistan - Rethinking water and urban design

BY MOEEN KHANWith the monsoon season now in full swing, residents of major urban centers in Pakistan will have to see sights they are all too familiar with – choked sewerage, overflowing gutters, blocked traffic and flooded streets. As inconvenient as these problems may be, there is much more at risk than what meets the eye.

With rising population, disordered urbanization, lack of environmentally sensitive policy-making, dwindling water resources, and climate change, major cities like Lahore are certain to find themselves in a precarious situation in the future if remedies are not introduced on an urgent basis.

Lahore’s single aquifer, for example, provides most of the water used for domestic purposes but the water table is declining by 2.5-3 feet per year due to over abstraction.

Much can be done to efficiently manage water resources in urban environments. Systematizing domestic water use, developing a well-planned water management system, introducing environmentally sensitive building technologies, and changing cultural norms dictating water use are important facets of such an approach. This is especially urgent if climate change resilient cities are to be developed in Pakistan.

Consider the manner in which major cities in the country are currently being developed. The two largest cities in the country – Lahore and Karachi, have lost greenery to urban sprawl. Both cities have also become concrete hardscapes that have brought about a new set of problems including, but not limited to, urban runoff and soaring temperatures during summers due to changing microclimate.

Concrete jungle:

Take Lahore and consider how asphalt and concrete infrastructure is being built with little to no attention paid to the environmental impact. During the monsoon (or even the occasional showers) sewerage systems are overwhelmed and valuable rainwater is simply discharged into sewers. This, despite the fact that virtually nothing of the water seeps down into the aquifer because there is very little open soil to absorb the moisture. Bear in mind that groundwater is also the primary source of water for a city of 12 million people, a resource that is being depleted at an alarming rate.

There are a number of solutions that have successfully been adopted by cities around the world. Roads, pavements, parking lots and other similar structures are now being built with pervious concrete and porous concrete.

Instead of causing flooding or being discharged into the sewers, such construction materials allow valuable rainwater to seep through to the aquifer.

In other words, a simple change in material use and design prevents urban flooding and stores water for future use, all with virtually the same structural integrity. While the initial costs are higher as compared to conventional concrete/ asphalt, the porous variety is significantly more affordable in the long run.

With a life expectancy of around 20 years, it has lower installation and life-cycle costs and does not necessarily require investment in stormwater management infrastructure such as stormwater gutters. There are other advantages associated with such a design approach as well. Reduced water on roads during rainfall decreases the likelihood of traffic accidents.

Here is an example of how efficient porous asphalt roads are at preventing runoff.

Video courtesy: City of Burnsville, USA.

Concrete or asphalt infrastructure also absorb more heat during the daytime and emits it during the night. According to studies, hardscapes are among the primary reasons why microclimate in a city is 3-4 degrees higher than surrounding areas, a phenomenon known as the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect.

A thermal image taken of a Melbourne street during a heatwave. Image courtesy: City of Melbourne

However, simple design changes, such as painting the surface in a brighter colour helps to reflect most of the heat absorbed from sunlight, thereby fighting off the heat island effect. The advantages, such an approach offers, are not just limited to water use either. Lower temperatures translate to reduced energy consumption and reduced risk of heat-related illnesses/mortality for the elderly, young and poor.

The design thinking extends to residential infrastructure too. Pavements and parking areas in residential areas are also built using conventional concrete. However, environment-friendly designs for such structures are now widely being adopted as well.

An example of a grow-through pavement style.

Not only designs, like a grow-through pavement, are aesthetically pleasing, but they also help absorb rainwater (or even domestic water) and keep temperatures cooler.

Rooftop design:

With average temperatures rising owing to climate change, urban areas will become dangerously hot, leading to a sharp spike in water and energy consumption. It is of urgent importance to introduce wide-scale strategies to circumvent the impending threat if cities are to cope with such stress.

One effective way to do this is to alter the manner in which the roofs are designed. Simply painting the roofs in white colour can reduce air temperatures above the building by a margin of several degrees.

Similarly, green roofs – covering the roof with vegetation, are not only pleasing for the senses and reduce stress, but can help to decrease the temperature inside the building, combat urban heat island effect, help in noise reduction, cut back on carbon emissions, improve biodiversity and air quality. Most of the rainwater is retained by the soil instead of being discharged into the sewers or streets, thereby providing an excellent rainwater management strategy. Excess rainwater can also be stored in a water tank for later use. Even vegetated mats and plugs have been designed for rapid deployment of green roofs at a massive scale. There are also financial advantages associated with the design philosophy. Green roofs are estimated to increase the life of a roof by 200% and have the added effect of reducing energy consumption due to lower demand for air conditioning.

A conceptual image demonstrating green roofs as part of Green Infrastructure.

Another landscaping design similar to green roof is the concept of green wall. Dubbed the ‘Living wall’ – the idea is to grow vegetation on the walls of a building. The method provides many of the same benefits as green roofs and is highly efficient in reducing building temperature and absorbing water.

In cities across the world, community-driven projects have been initiated to allow residents to grow food on roofs as well. Such a technique has the added advantage of providing valuable household income for the poor.

Given the threat of climate change, civic bodies around the globe have progressively introduced policies, technological solutions and changes to the manner in which urban centers are developed and organised.

Pakistan, a country that is among states most threatened by climate change, has given scant attention to the matter. Of course, the solutions mentioned here are by no means exhaustive nor comprehensive, doing so is beyond the scope of this writing.

The aforementioned designs and systems have as much to do with preventing urban flooding as with ensuring that valuable water resources are preserved, that urban temperatures remain under control in a rapidly warming planet, and that a conscious approach regarding urban design is integrated into a cohesive urban development policy as part of Pakistan’s climate change risk management strategy.

The Baloch And Pashtun Nationalist Movements In Pakistan: Colonial Legacy And The Failure Of State Policy – Analysis

By Kriti M. Shah

Introduction

The border lands between Afghanistan and Pakistan have been a hotbed for global terrorism and jihad for the last four decades. The causes are rooted in colonial legacy and the impact of British rule on the region. In the late 1800s, the perennial question for the British was how far the northwestern border should be pushed beyond the Indus.iThe sub-continent was seen as a “game board” for that era’s great powers such as Britain and Russia to expand their areas of influence and undercut one another. The British empire wanted to have a ruler in Afghanistan who would be sympathetic to their interests and guard against Russian expansion into Kabul. Three wars were fought (1828-42, 1879-80, and 1919) between the British and different Afghan Amirs. It was during the second of these Anglo-Afghan wars in 1893 that Amir Abdur Rahman, while negotiating with Mortimer Durand, a British diplomat in Kabul agreed, somewhat arbitrarily to the drawing of a border line between British India and Afghanistan. The state of Afghanistan therefore emerged mainly as a result of the laying down of borders, and not laborious state-building. This border would be called the ‘Durand Line’ and would demarcate the future nation states of Afghanistan and Pakistan. The border would have an impact on how the British dealt with the Pashtuns in the north and the Baloch in the south on their side of the Line.1

Given that the Pashtun and the Baloch have inhabited the region for centuries, they became crucial elements of Pakistan’s ethnic tapestry after the creation of the state in August 1947. Their place in Pakistani society today is an outcome of their geography, British colonial legacy, and their respective relationships with the state over time. The Pashtuns have borne the brunt of the Afghan jihad and military campaigns against their tribes for the past 40 years. The Baloch have had to deal with economic exploitation and the heavy-handedness of the Pakistan military.

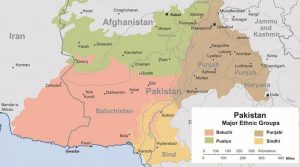

Major Ethnic Groups of Pakistan

1 The Pashtuns and the Baloch are large ethnic groups that span the region of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, and Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, respectively. While the census figures are not accurate, Pashtun make up some 15 percent, and the Baloch, over five percent of the population of Pakistan. Pashtuns are also the country’s second largest ethnic group after the Punjabis.

Since its inception, the Pakistani state has repressed ethno-linguistic identities (be it the Sindhi, Bengalis, Pashtun or Baloch) while pushing for an “Islamic” identity. In the popular narrative, therefore, the Pashtun and the Baloch have come to be associated with violence, militancy and aggression against the state. Their political grievances tend to be viewed in terms of their ethnicity; their intent is perennially questioned; and they receive proportionately greater media scrutiny for their alleged “anti-state activities”.

Over the years the Baloch nationalist movement has articulated various demands, including secession, greater political, economic and cultural rights, and political autonomy. The Pashtun movement, for its part, have been fighting for the creation of an independent state of Pashtunistan to include all Pashtuns from either side of the Durand Line, and greater political autonomy and independence within the state of Pakistan.

This paper places the Pashtun and the Baloch nationalist movements in a historical context, traces their evolution, and examines the drivers that have led them to this stage. The paper analyses the political, economic, demographic and socio-cultural trends that have characterised the Pashtun and Baloch movements over time, while highlighting how similar state policies—of economic exploitation and political repression—as well as Islamic militancy have led to different outcomes for the two populations

The Legacy of the British Empire

In the northwestern region of Pakistan, the Pashtuns have historically been influenced by their proximity to Kabul and, therefore, the Afghan king (in the west) and in turn, his relationship with British India (in the east). The spread of Pashtuns across the Durand Line established a transnational Pashtun community, with Pashtuns on either side of the Durand Line.ii This has allowed the Pashtun tribes to escape military pressure and move across the border from either side.

The British rightly feared that the Pashtun tribes, on their own or with help from across the border, would rebel against them and threaten the Indus heartland. They therefore maintained this region along the Afghanistan border as a buffer zone between Britain and Russia. Between 1849 and 1890, the British dispatched 42 military expeditions into the mountainous region, to subdue the rebelling Pashtun tribes. Unable to decisively defeat the Pashtun warriors, they adopted a policy that analysts would call “butcher and bolt”: they marched into an offending village, killed civilians, and fled before the tribal warriors could retaliate.

In 1901, the British integrated the region west of the Indus and east of the Durand line into the North West Frontier Province (NWFP). They adopted a policy of conciliation and control, backed by a massive military presence. The British built a number of forts and stationed troops in strategic points in the tribal areas.iii They allowed loyal tribes to trade in arms without restraint, and recruited them for military service. By 1915, the British had some 7,500 Pashtuns serving in the Indian Army.iv

The British strategy for dealing with the Pashtun’s local customs and power relations was based on three pillars: the tribal Maliks; political agents; and the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR). The Maliks served as local elite for the British: they ensured that British caravans could trade with Afghanistan through routes in the tribal areas, in return for benefits and subsidies. The political agent, meanwhile, was the senior bureaucrat who served as chief executive for different tribal agencies. He was the main contact for the tribal maliks, and was bestowed the power of suspending or cancelling the malik status when deemed necessary. The FCR was a set of criminal and civil laws that resolved intra-tribe conflicts according to tribal customs, or elements of Pashtun code (or Pashtunwali), such as the jirga.v Over time, maliks settled in the urban areas of Peshawar, Mardan, Kohat and Dera Ismail Khan, visiting their tribes occasionally and enjoying the benefits of their relationship with the British colonialists. This heightened the economic stratification of Pashtun society.

While the British vernacularised languages in other parts of India, they neglected the Pakhtun language and promoted Urdu instead, to force the Pashtuns to look to Punjab and India as part of a linguistic union.viPashtun leader Abdul Gaffar Khan, through his army of Khudai Khitmatgars,2 used the Pashto language as a symbol of Pakhtun identity.3 His political leanings brought him closer to Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, and his success earned the wrath of the Muslim League and the British elite in the region.viiAs the idea of partition grew and the creation of Pakistan became an eventuality, Gaffar Khan made a call for an independent Pashtunistan, although the concept was never clearly defined. After Partition, his leadership recognised the creation of Pakistan as a settled fact and espoused the reorganisation of provincial boundaries under which all Pashtuns would be united in a single province called Pakhtunistan.

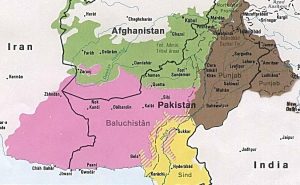

Meanwhile in the south, the region of Kalat (in present-day Balochistan) posed its own challenges for the British. Situated along the Iranian border with trade routes through Kandahar and southern Afghanistan, Balochistan’s strategic location has been of great importance to various nations, with Persian, Afghan, Sikh and British rulers making numerous attempts to gain control over it. While the different rulers of Kalat over the years attempted to bring the Baloch tribes under one political unit, weak institutions and political exploitation allowed the British to enter Balochistan.viii

Balochistan, Pakistan

2 The Khudai Khitmatgars, or Servants of God, was a non-violent movement led by Abdul Gaffar Khan against British rule in the North West Frontier Province. The movement inspired Pashtuns to lay down their arms and challenge the British in non-violent ways, similar to the tactics used by Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress Party during India’s freedom struggle.

2 The terms ‘Pashtun’ and ‘Pakhtun’ are almost interchangeable, therefore the language of the Pashtun is called Pashto or Pakhtun. The ‘Pathan’ however, as most in India refer to the group, is a term used solely by outsiders to refer to the Pashtuns.

Baloch tribes developed a sardar system in the early 15thcentury. The sardar would pledge loyalty to the Baloch Khan of Kalat and promise to defend the Khan’s kingdom against any outside attack.ix The position of the sardar was a crucial feature of membership in a Baloch tribe, and the ordinary Baloch were resigned to the leadership of the sardar. He was seen as a central and unifying presence, with the power to settle disputes between tribe members. The British would use this system to their advantage and force the Khannate to become a loose federation; over time, it became a ghost of its former self.x

The British appointed and bribed leaders amongst the Pashtuns as well. However, the concept of a sardar is absent from Pashtun society, where the main decision-making body is the institution of the jirga. The jirgaallows all adult male members of the tribe to collectively make decisions and prevents the concentration of power in a single individual. In such a system, the tribal leaders are accorded their power from within the tribe and not from their relation to the British. It was the opposite case in Balochistan, where support from the British allowed sardars to develop authority within their tribe. This helps to understand how the western frontier would evolve with its integration into Pakistan, and how the Pakistani state would dictate the frontier’s future.

The Khan of Kalat entered into an agreement with the British in 1839 which allowed them to trade and have military movements through Quetta, Bolan and Khojak passes, in return for a INR 50,000 subsidy.xi Over time, British involvement increased through further treaties, alliances with influential sardars, and military incursions. Within the next few years, the British annexed Sindh (1843) and Punjab (1849), extending their political footprint. The Khan of Kalat was left with no allies.

In 1877, Robert Sandeman was appointed as chief commissioner for the agency of Balochistan. He negotiated a treaty between the colonial government and the Khan of Kalat and his sardars, which allowed the British to consult and construct in the region as well as appoint a British agent to reside in the court of Kalat and settle disputes between the Khan and his sardars. The agreement reaffirmed the status of the Khan as a leader of an independent, albeit subordinate allied state.xii This helped the British thwart any resistance that grew amongst the local population against the Khan, who was now essentially an ‘agent’ or had at least accepted the growing clout of the British in their homeland. It was under this system that the role of sardars became part of a hierarchical British institution in the state. As the British gave sardars salaries, the fear of being denied money (which they knew would increase their influence within the tribe) forced sardars to follow British orders.xiii In 1883, the British leased Quetta, Marri-Bugti, the Bolan Pass under the name of “British Balochistan”. Except for the Marri-Bugti area, the rest of the British Balochistan region was Pashtun-dominated.

The colonial administration faced a number of social and administrative challenges as a result of their intrusion, despite treaties designed to “keep peace” with the Khan. While they continued to expand with the building of military cantonments, post offices and setting up telegraph and railway lines, the Baloch tribes put up resistance. In the years leading up to the departure of the British and the partition of India, small-scale attacks were conducted by the Baloch tribes, punctuated by a series of uprisings. In 1897, Pashtun warriors attacked British forces across the frontier.xiv Nonetheless, the British laid the foundation for the Balochistan agency, leaving Kalat (which was predominantly Baloch) free of colonial pressure.

On 12 August 1947, two days before the creation of Pakistan, Kalat declared its independence. After the creation of Pakistan, Kalat offered special relations in areas of defence and foreign affairs. Pakistan refused and demanded its integration into the new state.xv In March 1948, Pakistan annexed the entire region. A speech by Mir Ghous Bakhsh Bizenjo, a Baloch nationalist in 1947, summed up how the Baloch felt about joining Pakistan: “Pakistani officials are pressuring to join Pakistan, because Balochistan would not be able to sustain itself economically… we have minerals, we have petroleum and ports. The question is where would Pakistan be without us?”xvi

The British policy towards the Pashtun and the Baloch set the foundation for Pakistan’s state policy towards the two ethnic groups. While the Pashtuns were stereotyped as warriors and fighters, they were integrated into the army and allowed to govern themselves under FCR and certain aspects of the Pashtun tribal code. The Baloch were manipulated by coopting their leaders to support the British. Such a policy would continue as the state of Pakistan came into being.

The Role of State Policy

The partition of India in 1947 led to the creation of an ethnically and linguistically diverse Pakistan. While East Pakistan was more culturally and linguistically homogenous, West Pakistan was less so, with five major languages, various dialects, religions, castes and tribal identities. Many groups in Pakistan have similar cultural affiliations with groups outside the borders. The Pashtuns, for example, are also found in eastern Afghanistan, while the Baloch, in southern Afghanistan and Iran.

The state ideology was based on three founding principles: Islam would be the unifying force; Urdu would be the language of the people; and the military would be strengthened to counter “Hindu India”. Instead of establishing institutions that would accord equal rights to the various ethno-linguistic groups, the state projected Islam as their common denominator. The policy exacerbated ethnic divisions in the innately diverse nation; the assertion of any ethno-linguistic identity in the context of seeking political rights was seen as divisive.xvii

Each of these ethnic groups has had a unique path to mobilisation. Yet, across all of them, the drivers of ethnic conflict are largely the same: the lack of provincial autonomy; economic exploitation; and political and military oppression.

Lack of Provincial Autonomy

In the first few decades of Pakistan’s existence as a sovereign territory, the politics of the nation was defined by the government’s ‘One Unit’ plan. The scheme involved the integration of Punjab, Sindh, NWFP, and Balochistan into a single province of West Pakistan. The aim was to neutralise the Bengali majority in East Pakistan. It was strongly opposed by the people of NWFP, Balochistan and Sindh. By then, the Pashtuns had been coopted by the Pakistani leadership and were either part of mainstream politics or serving in the military and becoming the second largest ethnic group within the army. The One Unit plan thwarted any sort of autonomy for the different ethnic groups. In NWFP, Gaffar Khan led the movement against One Unit, undertaking tours across the tribal region to address rallies and raise ethno-nationalist consciousness against the plan.xviii The Pakistani state naturally saw the Pashtun nationalist leaders as projecting their Pashtun identity above their Islamic identity.xix

Following Kalat’s annexation in 1948, the Pakistani government announced that it would be treated in the same manner as it was during the British era.xx This meant the appointment of a political agent, entrusted with the powers to look after the state administration and guide the government on the internal matters of the state. The Baloch strongly resisted Pakistan assertion, seeing them as no different from the British. The government responded by banning political parties in Kalat and arresting the Baloch leadership. Over the years, the government in Islamabad has repeatedly tried to assimilate Baloch identity into the larger Pakistan identity. Since 1947, the state has engaged the Baloch in violent confrontations on five occasions (1948, 1958, 1962, 1973-77 and 2001 onwards).

The One Unit scheme sparked a violent uprising in Balochistan as the policy decreased Baloch representation at the federal level and forestalled the establishment of a provincial assembly, which had yet to be approved by the central government nearly a decade after Partition. The Khan of Kalat mobilised tribal leaders against the scheme which they saw as the federal government’s way of centralising power and limiting provincial autonomy. The government arrested the Baloch leaders and crushed the revolt. The province continued to be treated like a colony and the central government exploited the resources.xxi

Economic Exploitation

Deposits of natural gas were discovered in the Sui area of Balochistan in 1952 and piped to Punjab and Karachi soon after. Yet, it took 30 years for the gas supply to reach the capital city of Balochistan and that, too, because it was needed in the Quetta cantonment.xxii At the same time, skirmishes were regularly taking place between the tribal guerillas and the army, villages were being bombed, and rebel leaders arrested or killed. All this helped fuel anti-Pakistan sentiment.

Decades later, the sense of betrayal and exploitation that the Baloch have felt at the hands of the Pakistani establishment would continue. In the 1960s, a new generation of Baloch leaders emerged who were influenced by Marxist guerrilla movements in other parts of the world. They demanded the withdrawal of the Pakistani army from Baloch areas, the scrapping of the One Unit plan, and the restoration of a unified Balochistan. The movement was organised under the Baloch People’s Liberation Front and the fighting continued until Yahya Khan replaced Ayub Khan as Pakistan president and ended the One Unit plan. This led to the amalgamation of British Balochistan with the erstwhile state of Kalat, and thereby the merging of Pashtun and Baloch regions into one province of Balochistan.

Over the years, Balochistan has functioned as a Pakistani colony with its economy being run on the extraction of natural resources like minerals and hydrocarbon. The province, however, lags behind in physical and economic infrastructure, human capital, and investments. Moreover, the resources being extracted from its territory are processed elsewhere, leaving the people of Balochistan with little share of the revenues generated by the province.xxiii

In the tribal areas, the Pashtuns have been similarly neglected by the Pakistani state. The region is an important part of the Afghan poppy trade. The smuggling of illicit goods, including weapons and drugs across the border prompted the opening up of new trading and business opportunities for tribes in the region. As a result, posts in the Pakistani administrative and security apparatus in the border areas became highly lucrative, with agents getting a share of the profits being made by the smugglers.xxiv As Pakistan launched its military operations in the region, businesses and livelihoods were affected by the violence that followed, causing damage to the local economy. With no economic regulation nor a proper judicial system, and with the explosion of militancy-related violence, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas or FATA suffered over the years, and today remain significantly underdeveloped.4

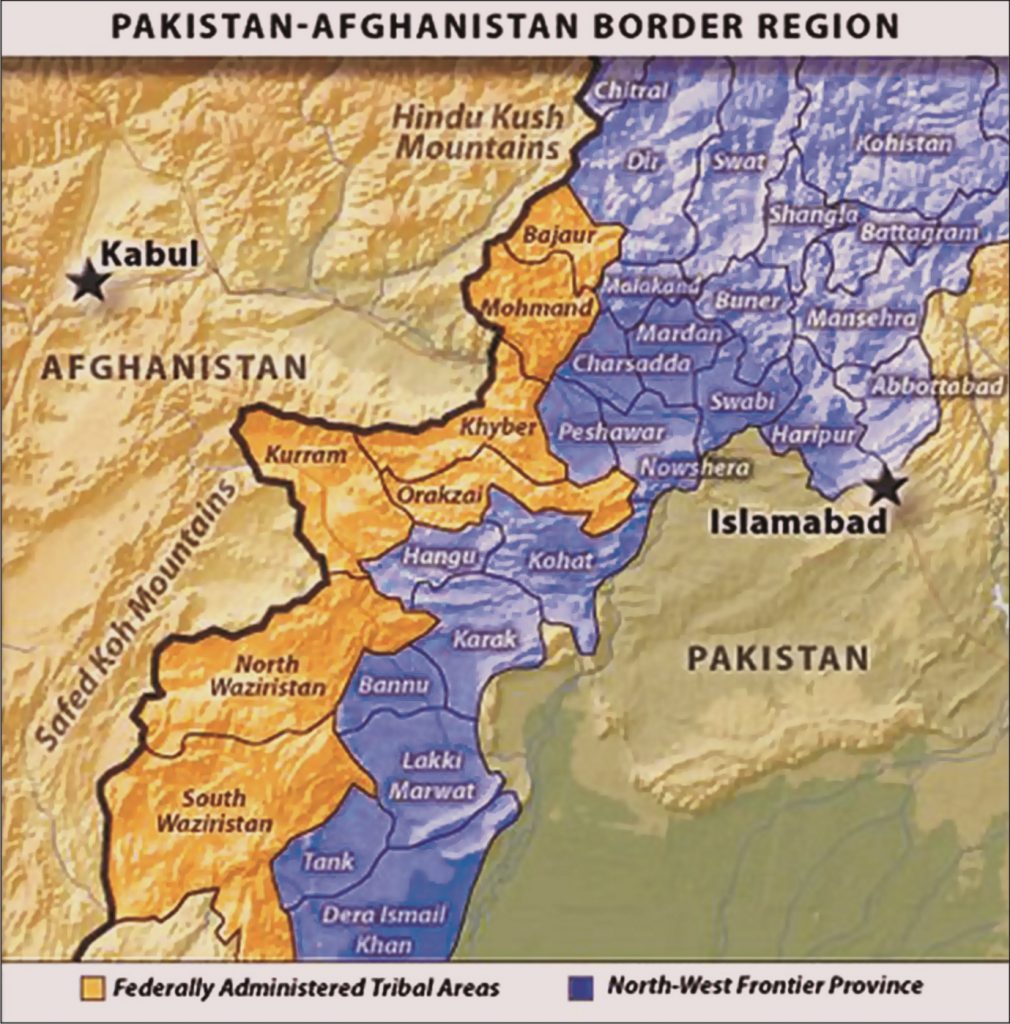

FATA and NWFP

4 For more information on FATA, read: Kriti M Shah, “Too Little, Too Late: The Mainstreaming of Pakistan’s Tribal Regions”, Observer Research Foundation, 28 June 2018, https://www.orfonline.org/research/41968-too-little-too-late-the-mainstreaming-of-pakistans-tribal-regions/

Political and Military Oppression

The National Awami Party (NAP) defined Pashtun and Balochi politics in the early decades of Pakistan’s creation. Formed in 1957, the NAP included noted Pashtun, Baloch, Sindhi and Bengali nationalist thinkers and politicians, whose objective was for greater autonomy for the non-Punjabi populations of the country.xxv In 1967, the party split into two factions over differences on how to achieve a socialist revolution. The pro-Soviet faction (which worked to achieve provincial autonomy in a democratic manner) was led by Wali Khan, the son of Gaffar Khan. In the 1970 election, the NAP-Wali faction emerged as the single largest party in Balochistan, forming a coalition government led by Sardar Atalluah Mengal along with the Islamic Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI). In NWFP, NAP-Wali put up an impressive performance as well. Fearing that NAP would make the western region especially Balochistan, another rebellious east Pakistan, then Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto dismissed the Mengal government nine months after its formation, accusing it of undermining the state, exceeding constitutional limits, and getting involved with the Iraqis and Russians. The sacking of the government—first in Balochistan and then in NWFP—frustrated any idea of provincial autonomy and set the stage for Balochistan’s fourth rebellion, which would engulf the province for the next four years.xxvi The NAP would return in 1986, evolving into the Awami National Party (ANP), an entirely Pakhtun nationalist party working in the tribal regions, NWFP and northern Balochistan.

In the late 1960s, Pakistan consolidated the administration of the tribal regions with the inclusion of Dir, Swat, Malakand and Hazara in NWFP, and leaving the rest of the tribal areas as they were, declaring them to be Federally Administered Tribal Areas or FATA and placing them under the president. Administratively, it consisted of seven political agencies and six frontier regions, that were controlled by political agents appointed by the federal government. However, the term “federally administered” is a misnomer as the tribal regions are not federally administered at all. Constitutionally, Islamabad has never maintained legal jurisdiction over more than 100 meters to the left and the right of a few paved roads in the tribal areas.xxvii

Beginning in the early 1970s, the Pakistan government began a massive social engineering experiment in the north. President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq pursued a policy of Islamisation, giving orders for instance for the construction of thousands of madrasas in the Pashtun areas. These emphasised the importance of Islam over ethnic identity and were largely funded by private Saudi agencies. The Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 intensified this policy, changing the nature of the western border permanently. Pakistan began supporting the Afghan resistance with material and financial support from the United States and Saudi Arabia. America’s interests were limited to stopping the spread of Soviet communist influence; for its part, Saudi Arabia, equally driven by the Iranian Revolution, worked to promote conservative Wahhabi Sunni Islam.

Zia received billions of American and Saudi aid that allowed him to strengthen Sunni madrassas and provide funding for militants to fight the Soviets. The promotion of Islamic identity and ideology during this time, created an atmosphere for the rise of the mullah or Islamic cleric, as a powerful leader. In the tribal areas, the mullahs engaged in misinformation campaigns, brainwashing and recruiting fighters from local mosques and madrassas for jihad. Jamaat-e-Islami, a radical Islamist party based in Peshawar at the time, was the first location for Saudi ‘charities and religious organisations’ to donate money, allowing the Saudi state to distance itself from the notion that it was officially supporting jihad. The war would reinforce the role of the madrassas as the first step in the process of recruiting and training fighters for jihad.xxviii

With the withdrawal of the Soviet Union from Afghanistan, thousands of mujahedeen across the Durand Line fought for power in Kabul. From 1996-2001, the Taliban, a predominantly Pashtun, Islamic fundamentalist group came to power. Backed by massive support from Pakistan, the group rose to power and led the continuing deconstruction and dismantling of traditional tribal structures, particularly in the Pashtun tribal areas. While majority of the commanders of the Taliban were Pashtun, the group has never reflected traditional Pashtun thinking and customs, nor does it seek to represent the interests of all Pashtuns.xxix In the years that followed, the Taliban would enforce their strict policies on Afghanistan: they imposed strict Islamic laws, forbade women from attending educational institutions or working, and banned television, music and non-Islamic holidays. The Taliban also provided sanctuary to al-Qaeda, the group responsible for the September 11 terror attacks, that would force the United States to return to South Asia, fight in Afghanistan and make deals with Pakistan.

The Conflagration of Pakistan’s Northwestern Border

The Aftermath of 9/11

In 2001, the US invaded Afghanistan to destroy al-Qaeda and the Taliban government that protected it. The war would bring monumental changes to Pakistan’s northwestern border. As the US battled the Taliban, thousands of militants fled across the border, settling in parts of Balochistan and FATA. As then president, Gen. Pervez Musharraf sought to support what the US called its “global war on terror”, the Pakistani army conducted operations in the tribal regions. Local militants joined the ranks of a new Taliban in FATA, which took the form of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan or TTP that established itself in the tribal areas as an alternative to the traditional tribal leadership system. The TTP killed hundreds of tribal elders in FATA who resisted their domination. Between 2004 and 2013, over a hundred maliks were killed in the tribal region,xxxdealing a blow to the Pashtun tribal structure.

Since the Soviet invasion of 1979, millions of Afghans have fled to Pakistan, changing the pre-existing tribal society.xxxi Through its network of militant Islamist groups, the Taliban relied on mosques in Pakistan and Saudi Arabia to recruit youth who had become isolated from their traditional tribal support networks. These were mostly in regions in the tribal belt where tribal structures have fallen through, areas with a high refugee population, and with little employment opportunities, if at all. Militants engaged in suicide bombings and ambushes, and used explosive devices across the tribal areas to target the army. Eventually, the “Talibanisation” of the north began to assume a global character as tactics used by Iraqi and al-Qaeda fighters started to appear in Pakistan. President Musharraf also decided to facilitate the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal or MMA, a conglomeration of religious parties, that gave political cover to extremists at that time and became part of the coalition government in Balochistan and government in NWFP.

The failure of the Pakistan Army to bring FATA under military control, compelled Musharraf to change strategy and pursue talks with the tribal leaders—this inadvertently allowed the tribal leaders fronting for the Taliban to establish autonomy in certain areas. The Shakai agreement in 2004 and the 2006 Miranshah agreement in North Waziristan, are only two examples of how the state gave in to the demands of the militants. These agreements saw the Army releasing all prisoners it had taken during fighting in the area; all seized weapons were returned, reparations for damages caused by the army were paid, and the army agreed to cease its patrols and dismantle temporary checkpoints within FATA.xxxii In exchange, militant religious leaders agreed to not shelter foreign militants. Within a year, the deal had collapsed and militants went back to fighting. Consequently, in 2006-2007, Afghanistan suffered an algebraic increase in violence.xxxiii

While the TTP ruled the north, the Afghan Taliban leadership fled from Kandahar to Balochistan. Mullah Omar and his aides established their new base in Quetta, which was not only the closest safe haven geographically but also the “friendliest” owing to the cultural similarities between the Afghan south and Balochistan.xxxiv This made the Baloch capital home to the Quetta Shura—the Taliban’s most important senior leadership council. While Pakistan would repeatedly deny that the Taliban had made Quetta their new base, it was the city where Mullah Omar would live before his mysterious death in 2013. His successor Mullah Akhtar Mansour would be killed by a US drone on a Balochistan highway in 2016, as he returned from Iran.xxxv

Military operations such as Zarb-e-Azb (launched in June 2014 and strengthened after the Peshawar school attack in December that year) and Radd-ul-Fassad (launched in February 2017 after a series of attacks in Sindh) have largely failed; after the military operations, the militants have also managed to simply find a new base in another part of Pakistan.

The inflow of refugees from Afghanistan as well has impacted the rise of religious extremism. Today, Quetta, given its location in the northern part of Balochistan—close to the tribal areas near the border, and with a rising Pashtun population—had become a focal point for Islamic terrorism. The mix of pent-up nationalism and inflow of militants has led to the creation of Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and other sectarian groups. As Saudi Arabia continues to finance Sunni Islam, and Iran promotes its brand of Shia Islam, given its territorial and social congruity with Balochistan this has played out in the systematic killing of Shia in the Baloch province.

The rise of religious extremism in Balochistan has been an excuse for the Pakistan army to target the Baloch population. The killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti in 2006 intensified the Baloch nationalists’ sentiments in launching a new rebellion against the state. His death brought about a generational shift in the authority structure of the Baloch nationalist movement—today a new leadership belonging to the middle-class Baloch has emerged. The movement has shifted from the traditional epicentre in the northeastern part of the province, to the rich urban south. Leaders such as Allah Nazar led the province’s fifth uprising, with the rebellion surpassing all previous ones in terms of its reach and sweeping sentiment against the state. Groups such as the Baloch Liberation Army, United Baloch Army and Baloch Liberation Force have threatened the province, displacing tens of thousands out of Baloch into nearby areas. Pakistan security forces used groups such as the LeJ and LeT to promote radical Islam and to balance and isolate the Baloch separatists.xxxvi While Pakistan continues to blame India and Afghanistan for supporting Baloch nationalists, it allows the Taliban and other extremist groups to find sanctuary in the province and form alliances with various other jihadi groups.

Strategic Realignments in Recent Years

In the last few years, geopolitical developments and subsequent domestic changes have impacted Pakistan’s northwestern border. Balochistan’s geostrategic importance and its energy reservoirs have been its curse. Just as the British made special policies in order to control and extend their power in Balochistan, the Pakistan state has been no different. The development of Gwadar, a port city in Balochistan, as a flagship project for the multi-billion-dollar China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has increased government and military authority in the province. Nationalists are opposed to the development of the port; they believe that they are the subject for subjugation and exploitation by the central authority. The influx of foreign workers has reinforced their claim that they will be reduced to a minority in their homeland. The establishment of army cantonments in Gwadar and across the state are seen by nationalists as the occupation of their homeland. While the Pakistan state says these developments will help modernise Balochistan and strengthen the country, nationalists see it as “internal colonialism”.xxxvii

While there have been multiple realignments in Balochistan over the last few years, these continue to be determined by strategic and economic priorities of the Pakistan military establishment, rather than a consequence of broader political compact for peace in the province.xxxviii In 2018 the Baloch Chief Minister from the PMLN was forced to resign after dissidents for within his own party (and others, including the JUI-F and ANP) voted against him. This led to the establishment of a new party, Balochistan Awami Party (BAP) which absorbed dissidents from rival parties, just a few months before the general election. The victory of BAP in the elections, demonstrates the military strength in political engineering and cobbling together of alliances that will work alongside them.

Over the years, there have been a number of attempts by governments to address Balochistan’s grievances. Some notable measures include the raising of provincial states within a federal structure defined in the 1973 Constitution, greater autonomy according to the 18th amendment to the Constitution (which also made Pakistan a parliamentary republic), and a larger percentage share of the National Finance Commission Award in 2009. While such measures may have provided short-term assurances, the nature of the state-province relationship has meant that the only change that has truly happened is that a new set of client-patron relationships has emerged.

The situation is similar in the north, where the state has tried to make amends but offering too little, too late. After decades of political lobbying and manoeuvring, Pakistan passed the 25th constitutional amendment in May 2018, which proposed the merging of FATA into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.xxxix While the merging of political, administrative and security structures will be long-drawn, predictably because of party affiliations with local groups and vested interests—the lack of political will amongst the provinces to finance the development of the tribal regions will ensure that the region remains underdeveloped. For decades, Pakistan has exerted military and “religious pressure” on the tribal regions, in the hope of using the region for their own security reasons, similar to how the British treated it as a frontier region to protect India. This policy has caused the breakdown of traditional, self-governing tribal structures. The support for mullahs as decision- and policymakers has not only harmed the Pashtun belt but has given rise to militants that target Pakistan; the result is a vicious cycle of killing and deceit.

For years, the people of Pakistan’s tribal region have not been treated equally like other citizens of the country. While Pashtuns enjoy representation in the army and in the government, the Pashtuns of the tribal region have long been discriminated against. Draconian laws such as FCR, drone strikes, and military operations have killed and displaced huge numbers, rekindling a new form of Pashtun identity.

These grievances have been best expressed by the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement or PTM, which began in the early months of 2018. The movement is a spontaneous reaction to the abduction and killing of a young Pashtun man, Naqeebullah Mehsud, in Karachi by the police. His killing sparked national outrage, with activists from his hometown of South Waziristan launching protest actions across the country to call for justice. While Mehsud is one such casualty, the movement brought to light the thousands of other Pashtuns and Baloch families who have been at the receiving end of the state’s repressive methods.

The demands of the movement are straightforward: an end to military abuse of power, restrictions on fundamental freedoms, enforced kidnappings and disappearances, and justice for those who have been victimised.xl Social media platforms have been awash with tweets, stories, photographs and videos of large rallies and sit-ins across the country. Manzoor Pashteen, the figurehead of the movement, organised protests in major cities such as Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad, Quetta and throughout the tribal belt (in Peshawar, Swat, Dera Ismail Khan, Bannu).xli The Pakistan media have been instructed to ignore the protest actions and have propagated the narrative that these activities are “anti-state”. By disregarding tribal divisions and sharing their stories of discrimination, torture and other forms of injustice, Pashtuns have united against the state in a non-violent manner. By coming together and speaking out against terrorism, they have distanced themselves from the idea that all Pashtuns are terrorists, calling an end to the militarisation of their land and the injustices being done to their communities. Their narrative is gaining popularity and is shaping the public discourse in the tribal belt as well as other minority-population areas across Pakistan.

Pashtun and Baloch Paths to Mobilisation

The Pashtun and Baloch nationalist movements have evolved, and continue to do so, influenced both by the domestic environment and the role of external political actors in the region. While there is economic activity in Balochistan—development projects are being undertaken and investments are pouring in— the people do not receive the direct benefits of such developments. There has also been no political reform and the Balochs continue to lack representation in the decision-making mechanisms. The leaders are widely viewed as being disengaged, unreliable and malleable, forcing the burgeoning middle class to assert themselves free from the clutches of the sardari system.xlii This middle class, driven by the legacy of past generations, finds itself part of the Baloch nationalist movement amidst the industrialisation and urbanisation being facilitated by CPEC. They are demanding their rights and claiming their stakes on the economic development of their province.

In the case of the Pashtuns, the PTM has become an unprecedented national movement. The leaders of PTM initially mobilised action on the historical problems of underdevelopment, neglect and discrimination. As the Pakistan military sought to bring down the PTM, there have been numerous reports of human rights violations being committed against the Pashtuns. Indeed, following the Soviet jihad and especially as a result of policies set down by the US and Pakistan after 9/11, the Pashtuns have found themselves associated with the Taliban, terrorism and militancy. For those who do have ideological sympathy for the Talban it is because of aspects of Pashtunwali (that dictates hospitality and safety for guests, that may be in this case, militants from Afghanistan who had fled into the tribal areas) and as a consequence of US operations and Pakistan military campaigns in the region. The movement, therefore, represents the Pashtuns’ fight for their constitutional rights. The fact that the PTM is non-violent, is in stark contrast to the number of Baloch rebellions which have advocated violence against state instruments.

While Pashtuns and Baloch have had a similar history and experience with regards to atrocities committed against them by the state, their movements have taken different paths. This section seeks to understand the different underlying themes of nationalism, religion and political and economic representation that must inform any analysis of the two movements.

1. Islamism vs nationalism

From Ayub Khan to Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan’s army elite has tried to forcefully promote a united country, favouring military action over political solutions to squash any separatist tendencies. Such a policy has only reinforced these sentiments. Former President Zia-ul-Haq was once quoted as saying he would “ideally like to break up the existing provinces and replace them with fifty-three small provinces, erasing ethnic identities from the map of Pakistan all together”.xliii

As Urdu was linked to the ideology of Muslim separatism and was projected as a major symbol for national integration, it made language an identity symbol for ethno-nationalists. Ethnic groups in East Pakistan, Sindh, Balochistan and NWFP have reacted by consolidating their identity, of which language is a defining aspect.

The Bengali and Sindh language movements have been violent. The ethnic tensions between the Urdu-speaking Mohajir and Sindhi speakers—manifesting in language riots and the splitting of Sindh’s provincial quota into Urban and Rural in 1972-73—planted the seeds for the creation of the political party, Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) in the 1980s. While groups have asserted their ethnic identity in the form of language, the Pashtun have been different. The Pashto language movement has decreased in intensity because the Pashtuns have integrated themselves in the mainstream to a certain degree, joining the army and bureaucracy in fairly large numbers.xliv

The division of Pakistan and creation of Bangladesh in 1971 shattered the myth that being Muslim was enough to unite the nation. Despite that, leaders such as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s, and Zia in the 1980s continued the policy of sectarianism and “divide and rule”. Rather than creating a national consciousness, however, the aggressive promotion of the Urdu language and Muslim identity became one of the major causes of the “Talibanisation” of the western border; it would drive the security establishment’s obsession with being anti-India. The Pakistan state’s quest for homogeneity created further faultlines within society and contributed to the emergence of radical Islamic groups across the country.

Pakistan’s ethno nationalists have all demanded greater political, economic and cultural autonomy for their group and region. Pashtun nationalists have tried to unite people on a more inclusive basis than tribalism. The call to create an independent Pashtun homeland (Pashtunistan) for all Pashtuns irrespective of tribal affiliations/ groupings and including Pashtuns from both sides of the Durand Line, had been a persistent feature of their politics, although it had since declined. While parties such as the ANP, which represents Pashtun interests, and the Pashtunkhwa Milli Awami Party or PMAP (which represents Pashtuns in Balochistan) have amassed support, their ability to form government has been controlled by other groups such as JUI (Islamic party) and other national parties. This is similar to 1947 when the Muslim League or the idea of a nation based on Islam, overwhelmed Gaffar Khan’s movement to create a Pashtun country.xlv

During the Afghan jihad, with the proliferation of madrassas, Islamists wanted to change the local Pashtun population’s tribal affiliation into religious affiliations, as Islam was the ‘tool’ used to fight the Soviets. Militants targeted tribal maliks, resulting in the collapse of the traditional tribal system. By eliminating the most powerful tribal leaders, the mullahs filled the political vacuum by providing religious motivation to the militants.

The British policy towards the Pashtun rested on identifying and ranking tribes in relation to one another, to determine which group was most strategically important over which region, and which sub-tribes relied on them, allocating allowances and subsidies on this basis. Years later, Pakistan identified Pashtuns and tribes based on whether or not they could forge a resistance to the Soviet invasion. By investing in the “idea of the tribe”, the military designed policies where Pashtun were motivated by religion and directed by tribal, cultural and religious principles.xlvi Although FATA was severely underdeveloped even before the rise of militancy, the decades of government neglect, archaic FCR laws and lack of investment in the region allowed a black economy and violence to flourish. As a result, military campaigns in the region after 2001 left residents more vulnerable to militant recruitment. While the government could have won over people’s hearts and minds and curbed extremism through institutional, political and economic changes to governance, it chose instead to empower those that would do its bidding and further alienate majority of the population.xlvii Therefore, while jihad initially helped suppress the Pashtun sentiments in the larger cause of jihad, it did not eliminate them.xlviii The PTM is a prime example of how ethnic nationalism in Pakistan continues to evolve today. The destruction of the tribal structures as a result of religious indoctrination and military campaigns has caused Pashtuns to seek a reversal of their fortunes and return to a time where their lives were governed by their tribal customs.

In Balochistan, the Pakistan government continues through the Ministry of Religious Affairs to set up madrassas to penetrate deeper into the Baloch areas that are opposed to the mullah. By harnessing the growing power of the clergy, they have manipulated elections, enabling religious parties such as Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam (JUI) to form the government. The rationale behind this policy is two-fold: the state assumes that this is the best way to entrench Islamic thought into society, engrain it amongst the Baloch so as to subdue their nationalist and separatist aspirations; the second is to propagate a disinformation campaign that equates Baloch resistance with Islamic terrorism. Pakistan intelligence services have linked nationalist militarism in the state to the terrorism of al-Qaeda and the Taliban, while ironically Baloch insurgents taking refuge in Afghanistan, sided with communist forces.xlix

2. Economic vs political motivation

Historical circumstances and social organisation of the Pashtun and Baloch have propelled their members along different routes to mobilisation. As Paul Titus highlights, neither route is entirely exclusive of the other. In post-colonial Balochistan, the Baloch have followed a predominantly political route while Pashtun have followed an economic route to mobilisation.l

The Baloch’s mobilisation has been of a political nature primarily due to the institution of the sardar in Baloch society and its tendency to create dynamic leaders at an ethnic-national level. Through the years a number of sardars have entered politics, aiming to convert their tribal standing into political power.li There has been no sincere effort or political will on the part of the British or the Pakistan state to change or curb the power of the sardar. As a sardar’s main interest remained in consolidating their land, the British focused on buying their loyalty, making them extensions of British authority in their particular region. This gave the British and later the Pakistan state indirect access over the natural resources in their territory. As the leader of his tribe, the sardar often acted against the interests of his people, accepting British financial assistance in exchange for submission to their authority. This policy has not only strengthened the sardari system over the years, it also inhibited the growth of a pan-Sardar solidarity.lii Different Baloch leaders have set up tribal guerillas and fighters in their territory, first to help the British, then to fight Pakistan over the years. Bugti, Mengal and Marri—the principal tribal chiefs in open rebellion against the government—are highly suspicious of each other. liiiThey have all led forces of thousands of loyalists: the Marri tribe formed the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA); Attaluah Mengal, leader of theBaloch National movement or BNM, which merged into the BNP; and the Jamhoori Wattan Party which has ties to the Bugti tribe. The leaders have remained divided across the political ideological spectrum, on how to deal with the Pakistan state. During the 1990 interim elections, Bugti split from the BNA, forming the Jamhoori Watan Party (JWP) which made an alliance with Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League. This has been a trend ever since, of factional rivalries leading to Baloch groups making alliances with national parties. In 1991, Mengal and the BNP formed a coalition with support of the PPP and in 1996 Zulfikar Magsi formed a government with support of PPP, PMLN and JUI.liv In 2010, after political lobbying and much struggle, the 18th amendment of the Pakistan Constitution was passed under the PPP government, whereby NWFP was renamed as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), in an effort to assuage the Pashtuns. It comprised seven agencies and 28 districts, and the tribal areas of FATA were left as they were.

Baloch ethnic identity gained greater importance in the post-colonial era because of resource competition with the Pashtuns. While this is partly because of the influx of Pashtun refugees fleeing the war in Afghanistan, it is important to recognise the legacy of the colonial era. While Balochistan remained poorer than any Pakistan region, the northern Pashtun areas achieved a greater deal of economic progress. This is partly due to the British construction of road and railway routes through the frontier region towards Afghanistan. As trade and troops flowed through the new routes, larger population centres grew. While there was economic development and new towns were being built along the railway lines in the south as well, the colonial development of the region favoured the Pashtun population in the north, more than the Baloch in the south.lvIn the Pashtun areas of Balochistan, there is evidence of economic success. Straddled across the Durand Line, Pashtuns have for generations controlled important trade and smuggling routes. Relative to the Baloch, they have been successful in professions such as transportation and construction. Given their historical ties to various regimes in northern India, the Pashtuns have developed networks and skills that have given them access to economic markets in Pakistan.lvi

The Baloch have felt a strong sense of political deprivation, due to their underrepresentation and underemployment at the federal level. They have felt much more alienated from the Punjabi establishment than have the Pashtuns. The perception is that the Punjabis, who dominate the state apparatus and representative institutions like the military and civil bureaucracy, look down on them as “primitive”, while favouring the Pashtuns.lvii Historically, the bulk of the Pakistan army has comprised Punjabis (70-75 percent), Pashtun (15-21 percent), with a small proportion of Sindhis and Mohajirs (3-5 percent) and Baloch (0.3 percent).lviii In addition, Pashtuns are well represented in all strata of the capitalist class, having established businesses in all provinces; in contrast, there is no significant Baloch capitalist class.lix

Conclusion

There is an oft-quoted way of describing the British colonialists’ approach to the historical ethnic tapestry in what is now Pakistan: “Rule the Punjabis, intimidate the Sindhis, buy the Pashtun and befriend the Baloch.”lxWhile it may have been a truism of how the British empire viewed the region, it also encapsulates the way the nation-state that is Pakistan has chosen to deal with the different ethnic groups within its territory.

Security experts are keeping a watchful eye on Pakistan’s western border with Afghanistan, given the potential for conflict in the region. After all, the tribal systems and culture of the Pashtuns of FATA have been irrevocably damaged, they continue to be economically deprived, and the military forces have them in a chokehold. The Pashtuns are left with few options. The loss of their homes, families, traditions and normalcy has not only pushed Pashtun society even further backwards, but has left them with no trust in the Pakistan government. External pressure on the tribal leaders has had no effect that is remotely beneficial to the state. It has instead forced the Pashtuns to take up arms, first against Pakistan’s enemies in Afghanistan and then against Pakistan itself. The rise and growth of the PTM threatens the Pakistan state, given its non-violent and democratic nature. It will take Pakistan nothing less than urgent, far-reaching steps to make amends for decades of brutality against the Pashtuns: restoration of the tribal structures; removal of arbitrary checkpoints; a return of those who have been taken by state forces without a trace; and a cessation of the military policy in the region.

In Balochistan, while the Baloch leaders make alliances for their own political and financial benefit, the people of the province are suffering and continue to be repressed. There is minimal representation of the people and there is a need for a drastic political change that takes into account the voices on the ground. Intra-Baloch rivalry, compounded by the paranoia of its leaders, has stunted Baloch politics. While the potential of a pan-Baloch party cannot be ruled out, the military’s meddling in electoral politics dampens hopes of real change in the grassroots. As projects under CPEC continue, there is the potential for a grassroots movement similar to PTM to emerge that will fight for adequate and fair representation in the government and development projects in the province.

The PTM continues to grow—battling state repression and the persecution and killing of its leaders—and carries the Pashtuns’ historical baggage. The Baloch and the Pashtun share a common history given injustices they have suffered in the hands of the Pakistan state. The demands of the nationalists have shifted from separatism (or calls for Pashtunishtan and Greater Balochistan) to working within the democratic system for fairer treatment and restoration of their fundamental rights. Non-violent, grassroots and non-political movements such as the PTM offer hopes of possible future cooperation between the Pashtun and Baloch people, to come together and assert their demands for their constitutional and human rights.

*About the author: Kriti M. Shah is a Junior Fellow with ORF. Her research focuses on Afghanistan and Pakistan’s foreign and domestic policy, their relationship with each other, the United States and the Taliban.

Source: This article was published by the Observer Research Foundation

Endnotes:

1 The Pashtuns and the Baloch are large ethnic groups that span the region of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, and Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, respectively. While the census figures are not accurate, Pashtun make up some 15 percent, and the Baloch, over five percent of the population of Pakistan. Pashtuns are also the country’s second largest ethnic group after the Punjabis.

2 The Khudai Khitmatgars, or Servants of God, was a non-violent movement led by Abdul Gaffar Khan against British rule in the North West Frontier Province. The movement inspired Pashtuns to lay down their arms and challenge the British in non-violent ways, similar to the tactics used by Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress Party during India’s freedom struggle.

3 The terms ‘Pashtun’ and ‘Pakhtun’ are almost interchangeable, therefore the language of the Pashtun is called Pashto or Pakhtun. The ‘Pathan’ however, as most in India refer to the group, is a term used solely by outsiders to refer to the Pashtuns.

4 For more information on FATA, read: Kriti M Shah, “Too Little, Too Late: The Mainstreaming of Pakistan’s Tribal Regions”, Observer Research Foundation, 28 June 2018, https://www.orfonline.org/research/41968-too-little-too-late-the-mainstreaming-of-pakistans-tribal-regions/

i Conrad Schetter, “The Durand Line: The Afghan-Pakistani Border Region between Pashtunistan, Tribalistan and Taliban”, Internationales Asienforum 44 (2013): 50, https://doi.org/10.11588/iaf.2013.44.1338

ii Paul Titus, “Honor the Baloch, Buy the Pashtun: Stereotypes, Social Organisation and History in Western Pakistan”, Modern Asian Studies 32, no. 3 (1998): 673

iii Titus, “Honor the Baloch”, 661

iv Ikramul Haq, “Pak-Afghan Drug Trade in Historical Perspective”, Asian Survey 36, no 10 (October 1996): 947, DOI:10.2307/2645627

v Kriti M. Shah, “Too Little, Too Late: The Mainstreaming of Pakistan’s Tribal Region”, Observer Research Foundation (June 2018)

vi Ashok Behuria, “State versus Nations in Pakistan: Sindhi, Baloch and Pakthun responses to Nation Building”, IDSA Monograph no. 43 (January 2015): 112

vii Ashok Behuria, “State versus Nations”, 113

viii Rehana Saeed Hashmi, “Baloch Ethnicity: an analysis of the issue and conflict with the state”, Journal of Research Society of Pakistan 52, no 1 (2015), 59

ix Behuria, “State versus Nations”, 87

x Behuria, “State versus Nations”, 87

xi Hashmi, “Baloch Ethnicity“, 59

xii Titus,” Honor the Baloch” ,661

xiii Hashmi, “Baloch Ethnicity“, 66

xiv Titus, “Honor the Baloch”, 662

xv Hashmi, “Baloch Ethnicity“, 62

xvi Hashmi, “Baloch Ethnicity“, 64

xvii Nazir Ahmad Mir, “Pashtun Nationalism in Search of Political Space and the State in Pakistan”, Strategic Analysis 42, No 4 (2018): 1, https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2018.1482629

xviii Syed Minhaj ul Hassan and Asma Gul, “One Unit Scheme: the role of Opposition focusing on Khyber Pakhtunkhwa”, Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan 55, no 1 (2018)

xix Behuria, “State versus Nations”, 115

xx Gulawar Khan, “Politics of nationalism, federalism and separatism: the case of Balochistan in Pakistan” (PhD dissertation, University of Westminster, 2014)

xxi Mickey Kupecz, “Pakistan’s Baloch Insurgency: History, Conflict Drivers, and Regional Implications”, International Affaires Review 10, no. 3 (Spring 2012): 101

xxii Sushant Sareen, “Balochistan: Forgotten War, Foresaken People”, Vivekananda International Foundation, September 2017: 45

xxiii Manzoor Ahmed and Akhtar Baloch, “The Political Economy of Development: A Critical Assessment of Balochistan, Pakistan”, Munich Personal RePEc Archive no. 80754, June 20, 2017

xxiv Conrad Schetter, “The Durand Line”, 64

xxv Nadeem F. Paracha, “The first left”, Dawn, November 9, 2014, https://www.dawn.com/news/1142900

xxvi Sareen, “Forgotten War, Foresaken People” 38

xxvii Thomas H. Johnson and M. Chris Mason, “No Sign until the Burst of Fire: Understanding the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier”, International Security 32, no. 4, (Spring 2008): 53, DOI: 10.1162/isec.2008.32.4.41

xxviii David Waterman, “Saudi Wahhabi Imperialism in Pakistan: History, Legacy, Contemporary Representations and Debates”, Mykolas Romeris University (2014)

xxix Kriti M. Shah, “The Pashtuns, the Taliban and America’s Longest War”, Asian Survey 57, no. 6 (November/December 2017), DOI: 10.1525/as.2017.57.6.981

xxx Dr. Muhmamad Akbar Malik, “Role of Malik in Tribal Society: A Dynamic Change after 9/11”, Pakistan Annual Research Journal 49 (2013)

xxxi “Timeline of Afghan displacements into Pakistan”, The New Humanitarian, February 27, 2012, http://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2012/02/27/timeline-afghan-displacements-pakistan

xxxii Johnson and Mason, “No Sign until the Burst of Fire”, 56

xxxiii Johnson and Mason, “No Sign until the Burst of Fire”,66

xxxiv Hassan Abbas, “ A Profile of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan””, CTC Sentinel, (January 2008)

xxxv Adam Entous and Jessica Donati, “How the US tracked and killed the leader of the Taliban”, The Wall Street Journal, May 25, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-tracked-taliban-leader-before-drone-strike-1464109562

xxxvi Malik Siraj Akbar, “In Balochistan, Dying Hopes for Peace”, The New York Times, July 19, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/19/opinion/pakistan-elections-balochistan-islamic-state.html

xxxvii Ian Talbot, Pakistan: A Modern History (London: Foundation Books, 2005): 416

xxxviii Ali Dayan Hasan, “Balochistan: Caught in the Fragility Trap”, United States Institute of Peace: 5

xxxix Amir Wasim, “President signs KP-FATA merger bill into law”, Dawn, May 31, 2018, https://www.dawn.com/news/1411156

xl Ali Wazir, “What does the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement Want?”. The Diplomat, April 27, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/04/what-does-the-pashtun-tahafuz-movement-want/

xli Manzoor Ahmad Pashteen, “The military says Pashtuns are traitors. We just want our rights”, The New York Times, February 11, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/11/opinion/pashtun-protests-pakistan.html

xlii Dr. Moonis Ahmer, “Why is the current Baloch nationalist movement different from the rest?”, Dawn, November 6, 2016, https://www.dawn.com/news/1294424

xliii Frederic Grare, “Pakistan: The Resurgence of Baluch Nationalism”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, (2006): 3 <https://carnegieendowment.org/files/CP65.Grare.FINAL.pdf>

xliv Tariq Rahman, “Language, Power and Ideology”, Economic and Political Weekly 37, no44/45 (November 2002), DOI: 10.2307/4412816

xlv Titus, “Honor the Baloch”, 678

xlvi Sana Haroor, “Competing views of Pashtun tribalism, Islam and Society in the Indo-Afghan borderlands” in Afghanistan’s Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban ed. Nile Green, University of California Press (2017): 161

xlvii “Pakistan: Countering Militancy in FATA”, International Crisis Group, no. 178, October 21, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/pakistan/pakistan-countering-militancy-fata

xlviii Nazir Ahmad Mir, “Pashtun Nationalism in search of Political Space in Pakistan”, Strategic Analysis 42, no 4, (2018): 445

xlix Frederic Grare, “Pakistan: The Resurgence of Baluch Nationalism”, 11

l Titus, “Honor the Baloch”

li Titus, “Honor the Baloch”. 679

lii “Balochis of Pakistan: On the Margins of History”, Foreign Policy Centre (2006): 31, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/26781/Balochis_Pakistan.pdf

liii For more on the how the sardars’ personal ambitions and rivalries inhibit Baloch nationalism see, Sushant Sareen, “Balochistan is no Bangladesh”, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, January 19, 2010, https://idsa.in/idsacomments/BalochistanisnoBangladesh_ssareen_190110

liv “Balochis of Pakistan: On the Margins of History”, 34

lv Talbot, “Pakistan: A Modern History”, 58

lvi Titus, “Honor the Baloch”, 677

lvii Sanchita Bhattacharya, “Pakistan’s Ethnic Entanglement”, Institute for Conflict Management 40, no. 3 (Fall 2015): 236

lviii Ayesha Siddiqa, Military Inc.: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy, (London: Pluto Press, 2006):59

lix Feroz Ahmed, “Ethnicity, Class and State in Pakistan”, Economic and Political Weekly 31, no 47 (November 1996)

lx Titus, “Honor the Baloch”, 1

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)