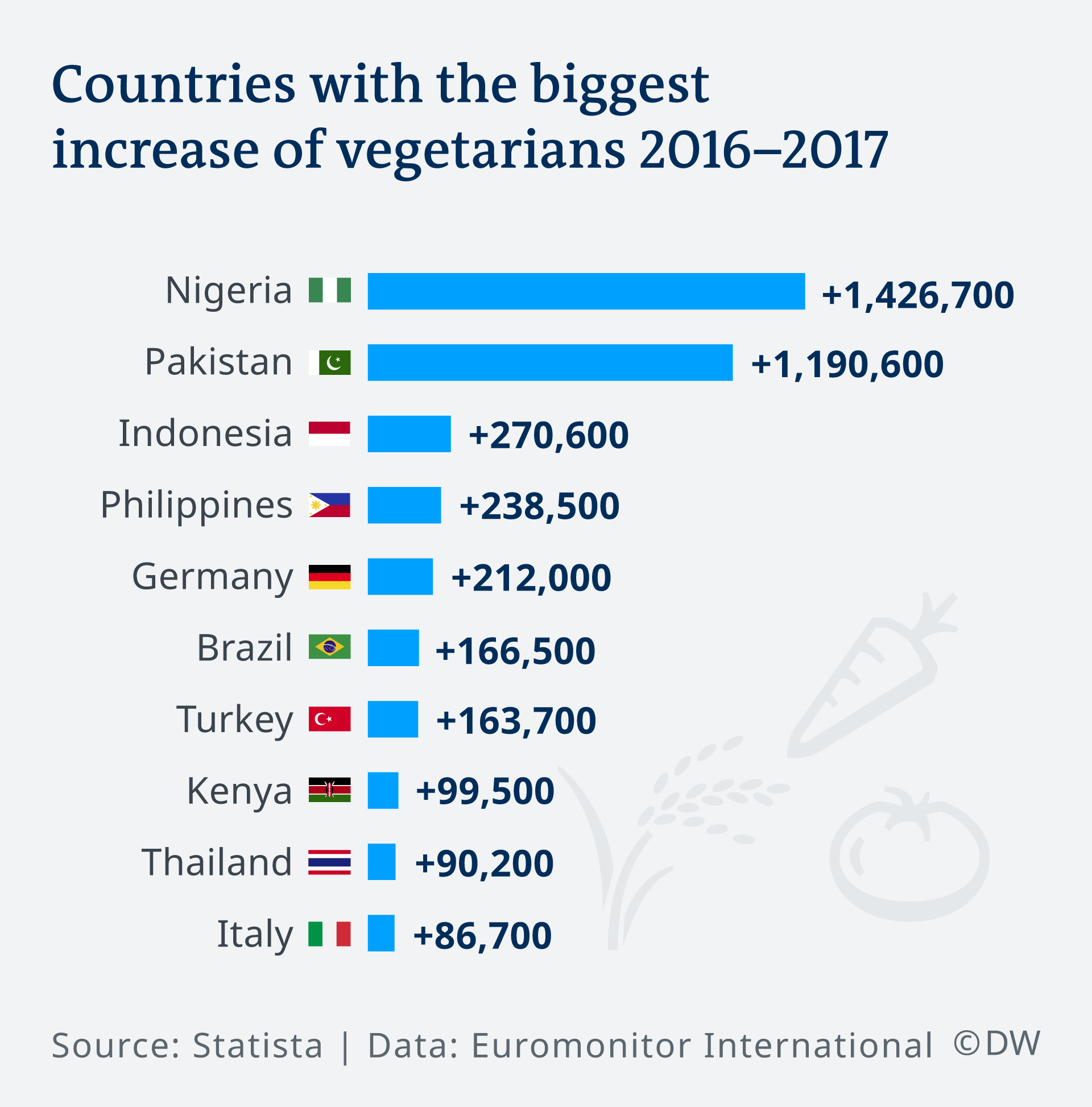

A recent report showed Pakistan to be the second-fastest growing vegetarian country in the world. Analysts say high inflation is impacting the food patterns of many Pakistanis, compelling them to give up eating meat.

Raja Ayub, a restaurateur in Islamabad, walks to a nearby shop every morning to buy vegetables for his restaurant. The 55-year old has been running the eatery for the past 10 years, but a new trend gaining popularity among Pakistanis is causing him concern – vegetarianism.

Many people in Pakistan are turning to a vegetarian diet for a range of reasons – the most obvious being rising prices of meat and growing poverty, as the economic activity in the South Asian country of 208 million people slows down.

The trend has Ayub both perturbed and anxious and has led him to change the meals offered at his restaurant.

"I don't know what happened to the Pakistanis. The transition in their dietary habits has forced a change in the menu of my restaurant," he told DW as he bought vegetables. "Their consumption of meat has significantly fallen and has already reached a new low."

But Ayub has some ideas as to what's behind the sudden change in the food demands of Pakistanis, who are usually known to be keen meat eaters.

He thinks that people might actually be concerned about their health and no longer prefer to have meat in their diet, or that they can no longer afford meat due to their shrinking wallets and earnings – a noticeable trend in the wake of

a slump in financial activity and rising inflation.

Ayub's views match the findings of a recent research showing trends across the world, with more and more people going vegetarian, especially in last couple of years.

The market study conducted by Euromonitor showed Pakistan to be the second-fastest growing vegetarian country with more than 1,190,600 people turning to vegetables.

The shop where Ayub comes to buy vegetable stays crowded every day, from dawn to dusk. The owner Rehan Awan, confirmed that demand for vegetables has increased substantially and his store is overwhelmed and struggling to cope.

"We have been bringing vegetables in abundance every morning, and very often these fresh vegetables vanish from the shelves very quickly," Awan told DW. "Now, at least three salesmen have been hired to manage the increased inflow of customers."

Rising inflation

Pakistan has previously been known as a meat-loving nation with a wide range of meat dishes such as Karahis, and beef, mutton and chicken grilled over coals or served in a curry.

An affordability issue among a large section of the middle class and the lower class has meant these people have cut down or even stopped eating meat. DW spoke to people who confirmed they had not turned vegetarian by choice but because they cannot afford meat.

Pakistan has previously been known as a meat-loving nation with a wide range of popular meat dishes

Shahnaz Begum, 40, a female domestic worker in Islamabad, told DW she is not happy about the rising meat prices. Even though she is earning more than last year, high currency devaluation means Begum struggles to feed her eight-member family.

"We were eating meat five times a month last year, but after Prime Minister Imran Khan came into power we now think many times [over whether] to buy meat once a month," Begum told DW. "Even the vegetable prices in Islamabad have risen double since Khan's government," she added.

Shahbaz Rana, an economic analyst, says it is "cost-push inflation that is gradually compelling people – mainly lower- and middle-income groups – to change their spending habits."

"About one-third loss in value of rupee against the US dollar in the past one year has led to a significant increase in prices of goods, including pulses that are also imported to meet domestic demands," Rana told DW. "The increase in cost of transport, gas and electricity has compelled the fixed income groups to readjust their spending within different commodities."

Pakistan Poultry Association officials confirmed the decline in demand for chicken due to current economic constraints and price hikes.

"The poultry business remained in loss. From the last nine months there was overproduction and the demand was too low, which never happened in the past," Saleem Akhtar, vice chairman of the Pakistan Poultry Association, told DW.

However, Akhtar believes the situation might get better over the next few years.

Declining meat business

Islamabad-based butcher Uzair Khan is not concerned about anything other than his business nowadays. After sitting in his meat shop with no customers for hours, he told DW that the rising prices have affected purchasing power, with unnecessary taxes imposed on millions of disadvantaged people.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) program has demanded structural reforms, which are hurting businessmen and low-income people.

Khan's government, which came into power in August 2018, is facing mounting economic pressures and hard austerity measures under a $6-billion bailout from the IMF, which is squeezing the lower- and middle-class people who brought Khan into power.

"The meat market is shrinking because of only one reason — the rising prices," Uzair Khan told DW.

Rana, who regularly writes on economy and financial markets, said the prices of red and white meat had significantly gone up in the last year due to inflationary expectations. The poultry feed, which is largely imported, and transport charges have also contributed to increasing prices of meat. This seemingly forced people to either reduce consumption or shift to a cheaper diet. The prices are unlikely to come down and there are no immediate signs of an increase in people purchasing power.

"Pakistanis may be turning to vegetables due to better health but it also because their meat-buying power has ended. The urban class is consciously increasing its intake of vegetables and fruits due to health reasons. Red meat and chicken prices have significantly gone up and there are no regulatory checks on these prices," said Rana.

Naeem Saleem has lost his chicken and pizza business due to higher taxes and a crackdown on businessmen. "We turned to vegetables and left eating meat after becoming jobless," Saleem told DW. "We are even using water to cook fish curry so that seven members of our family can eat. It should be fried or grilled."

Asghar Ali, an economics professor at the University of Karachi, estimates that more than 1 million people will lose their jobs and leave businesses, and more than 8 million could slip below the poverty line in the coming months.

"The economic situation remains in dire straits. The next two years, however, have been officially declared as years of economic stabilization, but there are very dim chances of economic recovery," Rana underlined.