Matt McAllester

During a TIME photo shoot it became immediately clear to TIME's Matt McAllester that Malala Yousafzai is no ordinary teenage girl.

Malala was late. She had finished school for the day and was in a car on the way to a photographer’s studio in the center of the English city of Birmingham, and the clock was ticking. The driver wasn’t answering his phone. The several people in the studio—technicians, make-up artists and photographer Mark Seliger—were hushed and increasingly anxious.

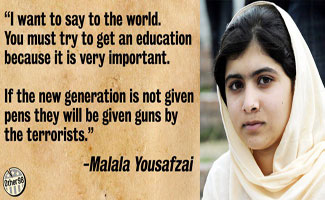

Eventually the car pulled up and out stepped Ziauddin Yousafzai, his son Kushal and Kushal’s older sister, a teenage girl famous not for singing or acting or being a social media star but for campaigning to enable girls in her native country and around the world to go to school and college and get the education their brothers often enjoyed. And who had, about six months earlier, been shot in the head by a Taliban gunman as she sat in her school bus. The Taliban were threatened by this fearless, teenage girl.

“I think of it often and imagine the scene clearly,” Malala had said before the assassination attempt. “Even if they come to kill me I will tell them what they are trying to do is wrong, that education is our basic right.”

In truth, before I met her, I had wondered whether Malala was entirely for real, whether such a young person could really be setting her own path in this way, or whether she was somewhat doing the bidding of her father, a charismatic school principal who also campaigned for the rights of girls to go to school. Was she much more than a symbol? She is still only 17, after all.

I accompanied Malala and her family into the building and up the elevator. And instantly I realized that Malala was different from other teenagers. She was about to sit for a TIME magazine cover shoot, for a photographer who has taken portraits of pretty much every famous person in the world. I expected her to be just a little bit excited. She had not sat for a portrait like this since she had been shot. But if she was excited she didn’t show it. It wasn’t that she was playing it cool; she was fine with it. But by that stage in her life she had been courted by thousands of media outlets and had received letters and visits and messages from some of the most important and celebrated people in the world. I quickly got the impression that she wisely saw all of that attention, including this photo shoot, as a tool to be used in the service of her cause and nothing else. She seemed preternaturally calm and focused.

As the makeup and wardrobe assistants prepared her—I had worried that she would scorn makeup and clothes that weren’t her own; she giggled a little and was fine with it—I asked her father about her cool. “She has always been like that,” he said, matter-of-factly and with a tinge of wonder. I also realized how wrong I had been to wonder whether Ziauddin was anything but a loving father. He was as protective as any father; one of his ways of showing his love was to let his daughter be herself and follow her passion, which he happened to share. More than any teenager I’ve ever met, Malala was simply her own person. Her father demonstrably respected and loved her for it.

Seliger began taking her picture, making her laugh and relax by telling her a funny story about how he had teased President Obama a little when taking his portrait, and I watched a computer screen as the images came through. She was so small that when she sat on a regular chair, an assistant had to put a green plastic crate and two planks of wood under her feet to raise her up.

Malala’s father talked to me about the injuries his daughter had suffered (she kept her hair brushed over the area on the side of her head where the gunman’s bullet had passed, miraculously not piercing her skull), how her school was going and how he did not see the family returning to Pakistan because of the danger they faced. They may have been rightly concerned for their safety, but neither Ziauddin or his daughter showed any inclination to let the Taliban, or any people who would rather girls did not receive the same educational opportunities as boys, win. Malala was not going to thank her blessings, justifiably feel that she had done what she could and settle into a quiet life in Birmingham. And so it has been. She has juggled school and celebrity and has tirelessly continued her campaign.

She will likely be touched that she’s won the Nobel Peace Prize, but I suspect she’ll see it in the same way she sees all of the accolades that come her way—as just another opportunity to encourage the mothers and fathers of the world to send their daughters to school.

No comments:

Post a Comment