Asad Ur Rehman & Sajid Amin Javed

The discourse on social protection in Pakistan is dominated by the hegemonic global standards, biased towards efficiency markings and ignoring local needs, demands and realities. The absence of attention to local socio-economic details grows out of the apathy and lack of political ownership.

Notwithstanding the economic constraints, this over-emphasis on efficacy markings and political ownership, mainly guided by vote exchange, are important factors behind the dismissal situation of social sector development indices in Pakistan.

Historically, social protection in Pakistan is unerringly confounded with and limited to poverty alleviation - add that consumption smoothing is confused with the alleviation of poverty and providing elementary skills remain the magic bullet to eradicate poverty.

This reductive view of social protection is probably a result of the policy regime of Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs), made compulsory by international lending institutes for all developing countries to acquire stability and development finance. This policy regime has not only directly shaped the social and fiscal parameters of social protection but also the contours of its discourse and design of social policy broadly.

Pakistan is an interesting case study where economy has grown without development, wrote Easterly at the beginning of the new millennium. According to the World Bank, Pakistan has reduced its poor population by 35 percentage points between 2002 to 2014, from 64.3 percent to 29 percent. Bravo!

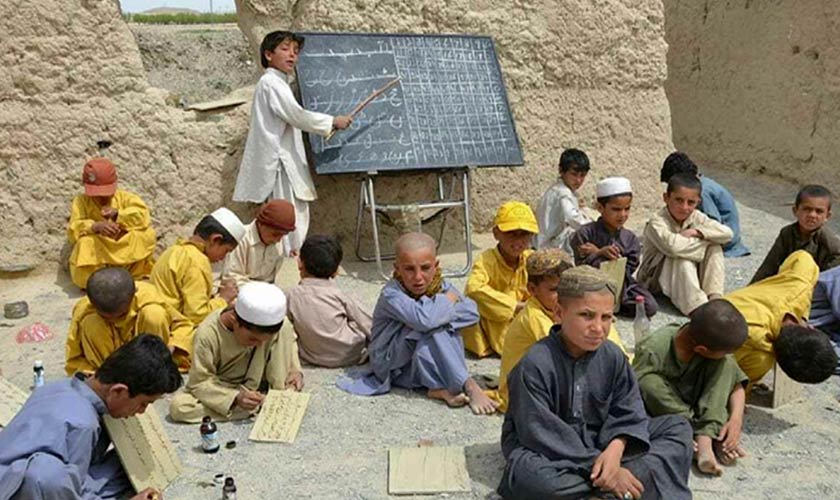

Pakistan’s performance, on the front of social development, is dismal. In South Asia, it is only better than Afghanistan — a country that has hardly seen any functional government for fifty years. Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh have started from a near similar position of human development.

We argue that poverty is output while exclusion is a cause. Poverty is absolute while exclusion is relational and sensitive to both time and space. All poor could be facing extreme exclusion but not all excluded are poor. Going beyond the geographical horizon, social exclusion has economic sociological and ideological dimensions. Illiteracy, unemployment, occupational choices, gender, caste, old age, disability, lower social capital interact to structure the social exclusion trap.It shall be interesting to note, however, that this poverty reduction is not supported by any tangible improvement in Pakistan’s Human Development Index (HDI). Performance in HDI did not match the same scale. In other words, this exit from poverty has no sustainable foundations.

These millions of people who came out of poverty without any sustained foundations, and who are no more eligible to benefit from public social protection programs, remain vulnerable. Hovering around the poverty line, this group can fall below it in the face of any external shock or physical accident.

The silence of social protection regarding this group is particularly disturbing. This silence is a by-product of conscious neglect to the existing structural inequalities causing and creating unequal access to services, opportunities, and institutions.

Pakistan’s performance, on the front of social development, is dismal. In South Asia, it is only better than Afghanistan — a country that has hardly seen any functional government for fifty years. Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh have started from a near similar position of human development. In the year 1990 their comparative HDI scores were 0.408, 0.431 and 0.382 while in 2018 their current HDI rank of them is 0.56, 0.647 and 0.614, respectively.

Additionally, India and Bangladesh were not just able to reduce their absolute poverty numbers but were also able to reduce social exclusion through affirmative action policies. The inequality adjusted-HDI (IHDI) of these countries indicates that the inequality within the population in access to social services is highest in Pakistan.

Dr Nadeem ul Haq referred to a somewhat similar idea in his recent PIDE blog posts. We, however, maintain that the exclusion is not limited to geography, as Dr. Haq seems to be stressing upon. We argue that the incidence of exclusion is circumscribed by both time and space. Limiting exclusion to geography seems coming out of equating social exclusion with poverty.

Social exclusion and poverty

The range of the axis of exclusion not only hints at the breadth of the factors that negatively affect the opportunities of social mobility and development but also highlights the structural realities that put a huge population of non-poor prone to different forms of vulnerabilities. This is in sharp contrast to the comprehension and practice of social exclusion in Pakistan, where only poor are considered to be experiencing social exclusion.

A recent study on social exclusion in Pakistan provides a glimpse into the prevalence of social exclusion by its different dimensions - material resources, education, and skills, health and disability, personal safety, social security - that can affect the life chances and outcomes of an individual and families. The study documented exclusion and its degree using categories of age, region, employment status. The degree of the severity of exclusion namely, minor, marginal and deep exclusion, was developed to capture the multidimensionality of the malaise.

Findings show that a majority of the population is facing some form of exclusion. But gender, age and region best explain its incidence and spread. For example, around 79 percent of the male population suffers minor exclusion - exclusion in at least one of the dimensions listed above-while this ratio is 82.9pc for women. Those facing exclusion in any two of the said dimensions - marginal exclusion - are 53.7 percent and 64.7 percent respectively. Pakistan’s performance, on the front of social development, is dismal. In South Asia, it is only better than Afghanistan — a country that has hardly seen any functional government for fifty years. Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh have started from a near similar position in human development.

The study also finds that being aged, women and belonging to Balochistan and Pakhtunkhwa increases the severity of exclusion. Most importantly, almost half of Pakistanis face marginal social exclusion. This indicates that a majority of the Pakistani population is facing one or other forms of disadvantage. The high rates of marginal exclusion denote exclusion from two of the said domains. No social protection program covers this part of the population if they do not strictly fall below the poverty line.

The size of marginal social exclusion, across gender and regional axis, is also very high. The gap between gender inequality, to access different resources, institution and services are also comparatively high in Balochistan and Pakhtunkhwa provinces. This is certainly also indicative of the problems of physical connectivity that directly hurt women more.

The existence of marginal social exclusion reflects the existence of exclusion for non-poor. This group does not always belong to an extremely poor category, but the vagaries of social circumstances and economic shocks do make them wanting social security and support. The vulnerabilities of this cohort increase and decrease over different periods of these life cycles. Social protection policy is just silent about the problems of these cohort making up the largest share of Pakistan’s population. Article 38 of the Constitution of Pakistan and all its clauses (a to g) categorically state the obligation of a state towards its citizens. Looking at it as some form of charity ignores the fact that the dismal economic performance of Pakistan in the last three decades correlates with dwindling social expenditure. Notwithstanding the issues of endogeneity, economic growth will supply resources for social expenditure or vice versa, the example of all middle-income countries reflects a higher expenditure on social development. The experiences of East Asian economies as well as Bangladesh and India imply that structural inequities are inversely proportional to human development, and human development is directly proportional to economic growth.

Pakistan should focus on expanding the scope of its social protection from alleviating poverty to reducing inequality and eliminating all forms of social exclusion. Changing the policy focus is not a choice any longer but an essential task to be done as soon as possible.

It is high time that we should go beyond the idea of poverty and deal with the larger issue of social exclusion. The current discourse on poverty rationalizes and legitimizes itself by aligning with the discourse on human rights. Bringing back social citizenship as a driver and objective of social policy must not be delayed any further.

No comments:

Post a Comment