Dr Abdus Salam won the 1979 Nobel Prize for physics. But in his home country Pakistan, he is all but forgotten because of his religious affiliation.

Exactly 22 years ago, on 21 November 1996, one of Pakistan’s greatest scientists passed away, largely unsung.

It hardly seemed to matter to his countrymen that he was the first Pakistani, and only the second Muslim after Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat, to be awarded a Nobel Prize. What seemed to matter more was the fact that he was an Ahmadi, and thus, not a ‘Muslim’ according to Pakistani law.

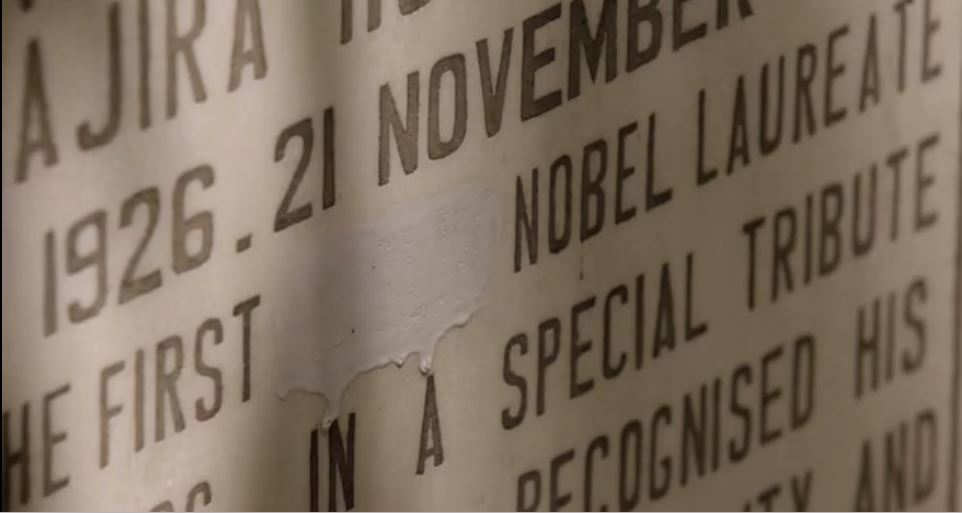

Then, at the beginning of 2018, came a documentary, which begins with the shot of a tomb in Rabwah, home of the Ahmadiyya community. The camera zooms in to identify it as the resting place of Prof. Muhammad Abdus Salam, who in 1979 became the first ______ Nobel Laureate for his work in physics. The blank is created by the word ‘Muslim’ being painted over.

The documentary, titled Salam: The First Muslim Nobel Laureate, has been produced after 14 years of arduous research. While the producers, Omar Vandal and Zakir Thaver, are from Pakistan, the director is New York-based Indian-origin documentary filmmaker Anand Kamalakar.

The film captures Salam’s life, death and disappearance from public memory, and attempts to reintroduce him to the modern audience. None other than former army chief, president of Pakistan and the architect of the Kargil invasion, Pervez Musharraf, has donated money for making the film, along with 378 others.

In an email interview, Kamalakar told ThePrint that he was inspired to join this project in 2015 because Salam was a curious mix of ‘man of science’ and ‘man of religion’.

“I wanted to investigate this contradiction, where on one hand he is working at the highest levels of science, by default trying to make the idea of god obsolete, but at the same time is deeply religious and steadfast in his beliefs,” Kamalakar said.

Tragically, there seems to be no direct way for Salam’s own countrymen to learn about his achievements. It is risky to publicly exhibit the film in Pakistan in the current climate, as many extremist Muslims believe that Ahmadis violate the fundamental prescription of Islam: The uncompromising belief in the finality of the Prophet Mohammad. In recent years, violence against the Ahmadi community has grown significantly and several have even been killed for holding on to their faith.

Who was Salam?

Salam was born on 29 January 1926 in Jhang, undivided Punjab, to parents who were part of the Ahmadiyya movement.

A child prodigy, he topped Panjab University’s matriculation examination at the age of 14. He was greatly inspired by Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, and based his final year undergraduate thesis on the latter’s work.

Salam’s brilliance earned him laurels at the University of Cambridge, including the prestigious Smith’s Prize. In 1949, he completed his doctoral studies from Cambridge in electrodynamics, only to return in 1954 as professor.

He went on to leave an indelible impact on the scientific infrastructure of Pakistan, helping set up some of its most prominent scientific institutions, such as the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission, the Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission and the Karachi Nuclear Power Plant.

Salam’s stint as scientific adviser to the President of Pakistan from 1961 to 1974 was an elaborate effort to help restructure the country’s scientific landscape and encourage people to purse their careers and life goals in the field of science. However, in 1974, prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto led the Pakistani parliament to pass a bill declaring Ahmadis as non-Muslims, leading Salam to first oppose the law and then leave the country.

At the international level, Salam’s gift to science was his proposal to form the International Centre for Theoretical Physics, which he wanted to dedicate to researchers from developing countries. It was ultimately set up in Trieste, Italy, in 1964, facilitating research in “physical and mathematical sciences”. The ICTP was renamed the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics in 1997 in his honour.

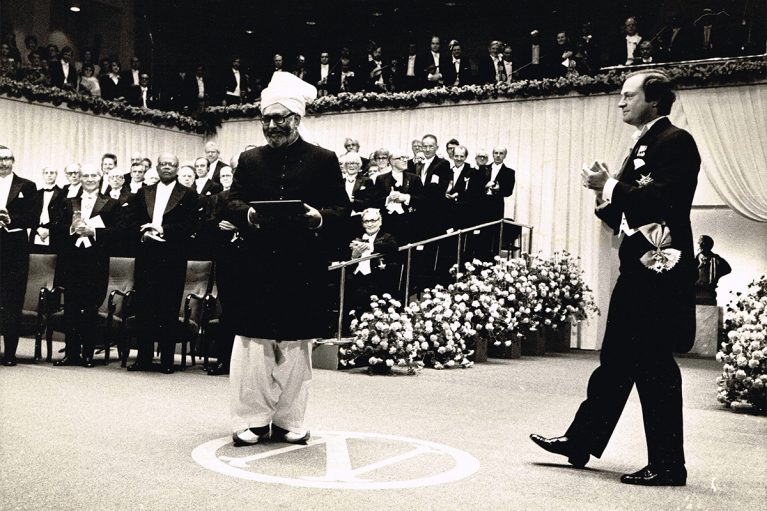

His greatest achievement, though, was the 1979 Nobel Prize in physics, which he shared with Harvard physicists Steven Weinberg and Sheldon Glashow. The prize was awarded “for their contributions to the theory of the unified weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, including, inter alia, the prediction of the weak neutral current”, as per the Nobel Prize Foundation website. Only one other Pakistani has been awarded a Nobel Prize since — Malala Yousafzai in 2014.

Salam worked and collaborated with several scientists, not limited to Americans or Britons. In collaboration with Indian-American physicist Jogesh Pati, Salam postulated a model which was an integral part of the grand unification theories — an attempt to explain the universe by looking at different forces of nature.

Salam died of a rare disease called progressive supranuclear palsy, a brain disorder that causes serious balance related problems.

A tale of two documentaries

Salam: The First Muslim Nobel Laureate has bagged awards at the Chicago, Washington and Seattle South Asian Film Festivals, and has been screened at several international festivals, including India’s Mumbai International Film Festival. It will be next screened in December at New York’s South Asian International Film Festival.

Kamalakar told ThePrint that the producers were “aspiring scientists” who “had always had to look to the West to be inspired, in spite of having an accomplished person who was born in their own nation. So they decided to make a film about him to spread his story and inspire the generations to come”.

“I am of Indian origin and the producers are Pakistani. We were all inspired by the story and legacy of Abdus Salam. Salam in turn was inspired by the great mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan to pursue a career in Mathematics and Physics. The camaraderie we as filmmakers developed during the process of making this film showed how similar we are in so many ways and share some of the same issues. We sincerely hope that this poses as an example for all to work towards a better relationship between the peoples of the two nations, in intellectual spheres and others,” Kamalakar told ThePrint.

This is actually the second major attempt to document Salam’s life, the first having been in 1996 by Dr Pervez Hoodbhoy, Pakistan’s noted nuclear physicist and a former student and admirer of Salam.

Hoodbhoy’s documentary, though, was drastically altered by a producer with the state-run Pakistan Television (PTV). Hoodbhoy told ThePrint in an email interview that the producer, an “Ahmadi-hater”, had deleted all the materials gathered over the course of a full year, and labelled it “plain sabotage”.

The altered documentary was aired a day after Salam’s death.

Asked why he had called Salam a “tragic figure” in the documentary, Hoodbhoy said, “Abdus Salam loved Pakistan. It badly mistreated him but he chose to blame it on a clique of mullahs and fanatics rather than the whole country. His greater disappointment was that he proved powerless in bringing science to Islam. Like the tragic figure Sisyphus who kept pushing a boulder up the hill only to have it roll back again and again, he kept trying and trying. It broke his heart that Muslim governments would not listen to him.”

How Pakistan treated Salam after 1974

Pakistan did award Salam its highest civilian honour, Nishan-e-Imtiaz, in 1979. Journalist and public intellectual Tariq Ali in his 2018 documentary, however, pointed out that military ruler Zia-ul-Haq could have done this mainly for “opportunism”, which “gave him a liberal image in the West”.

The documentary is a reminder that Salam’s achievements are largely unknown to his own compatriots. His name has been virtually erased from school and college curriculums and students at his own alma mater, Lahore’s Government College, admit they don’t know much about the scale of his accomplishments.

Pakistan rejected the proposal to name him UNESCO’s director general, the proposal to name Quaid-i-Azam University’s physics department after him was opposed and although his funeral was attended by many of his devout supporters and well-wishers, no official from the government came to offer condolences.

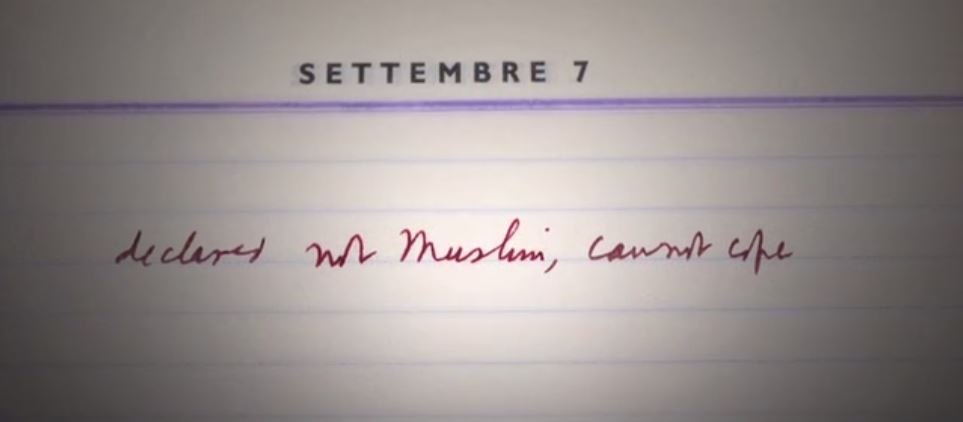

When Salam quit as scientific adviser to the president of Pakistan in 1974, he made an entry in his diary that read: “Declared non-Muslim, cannot cope.”

His countrymen have proven his pessimism was justified.

No comments:

Post a Comment