http://afpak.foreignpolicy.com/

By Ziad Haider

For just as Malala's mistake was being a girl, Salam's was being a member of the Ahmadi sect - a religious group declared to be non-Muslims in a 1974 constitutional amendment.

For just as Malala's mistake was being a girl, Salam's was being a member of the Ahmadi sect - a religious group declared to be non-Muslims in a 1974 constitutional amendment.

On Friday, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, passing over a remarkable top contender: Malala Yousafzai, a 16-year-old girl from Pakistan who was shot in the head by the Taliban last year for speaking out about girls' education. Instead of falling silent, Yousafzai's voice has only grown louder since the attack. She continues to champion her cause for a land to which she cannot return; the Taliban renewed their death threats against her this week. While she is surrounded by well-wishers on her current visit to the United States, perhaps no one can share her sense of acclaim and exclusion as well as Pakistan's (still) only Nobel laureate, Dr. Abdus Salam.

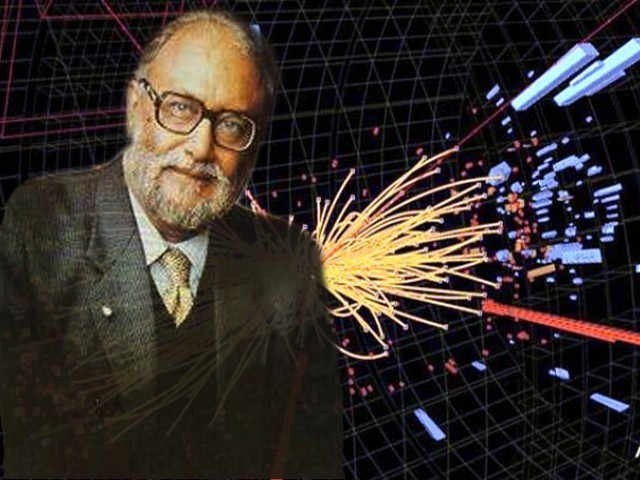

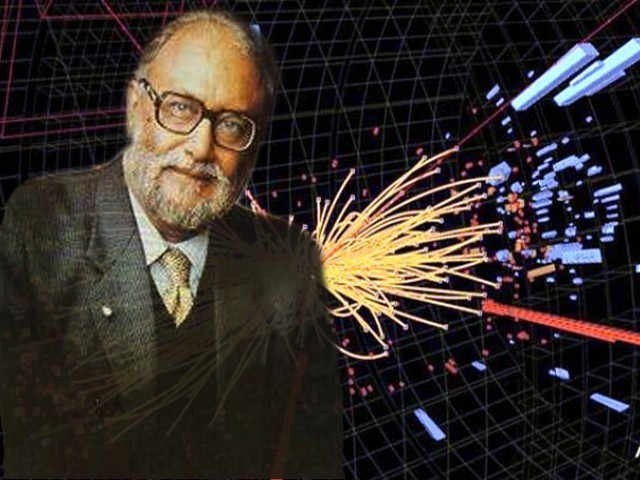

Salam was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1979 for his work on characterizing what is now known as the Higgs boson particle. Coincidentally, this year the Nobel Prize in Physics was shared by Peter Higgs, after whom the particle is named. Dubbed the "God particle," the Higgs boson is viewed as a potential building block of the universe. While some of Salam's critics might have cried heresy at his work, they instead chose to do so about his faith.

For just as Malala's mistake was being a girl, Salam's was being a member of the Ahmadi sect - a religious group declared to be non-Muslims in a 1974 constitutional amendment. After the amendment passed, Salam resigned from his government post. A Nobel prize five years later engendered no rapturous embrace upon his return home. Pakistan's leaders chose to keep him at arm's length. Even the word "Muslim" in the "first Muslim Nobel laureate" engraved on his tombstone is painted over. His colleagues continue to speak with equal wonder of his work and sadness for his treatment.

It is one of the many contradictions of Pakistan that the very town, Jhang, which produced a man of Salam's learning -- one who sought to unlock the secrets of the cosmos -- now produces parochial militancy. A militancy that has metastasized like a cancer in Pakistan and now consumes its children. When she first heard of the Taliban's threats against her, Yousafzai feared not for her own safety but for her father's. In a recent interview on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart she said that she thought the Taliban would never stoop to attacking a young girl. She was wrong.

To be sure, many Pakistanis are ambivalent about Yousafzai. In an environment rampant with anti-American sentiment and conspiracy theories, some view praise for her a way of shaming Pakistan. Others question the degree of attention merited to one individual when over 5,000 lives have reportedly been lost to terrorism over the past five years. Weariness with the West's fascination with the latest "victim" from Pakistan has also emerged. A few years ago, for instance, U.S. media outlets were abuzz with stories about another Pakistani woman who had been brutally raped and had similarly channeled her tragedy into championing women's rights.

Such cynicism, however, is of less import than the pernicious politics of exclusion in Pakistan -- a politics whereby one segment of society fervently believes it has a monopoly over deen (faith) and duniya (world). At best, the other is inferior; at worst, he or she merits elimination. It's an exclusionary system whereby individuals as different as a physicist and a teenage girl continue to be pushed outside society's bounds - either by force or by law. Nobel laureates, usually feted in other countries, seem strangely destined to be banished in Pakistan.

Much ink has been spilt on Pakistan's troubles, which seem to know no end. Yet the same country produced a young girl who is optimistically forging ahead, despite the horror she has experienced. Malala Yousafzai channels Pakistan's remarkable resilience. That she did not win the Nobel Peace Prize is thus ultimately irrelevant. What really matters is when can she go home.

For just as Malala's mistake was being a girl, Salam's was being a member of the Ahmadi sect - a religious group declared to be non-Muslims in a 1974 constitutional amendment.

No comments:

Post a Comment