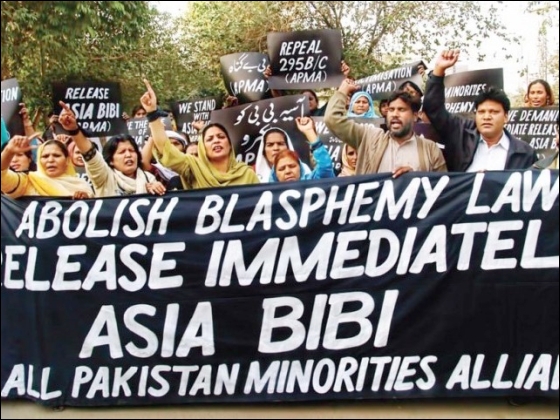

BY: Chaudhry Faisal HussainTHE concept of a Muslim state vis-à-vis its minorities, as envisaged by those that oversaw the creation of Pakistan and the members of the first Constituent Assembly, is hardly understood today. In his Aug 11, 1947 speech, Mohammad Ali Jinnah delivered a message of freedom to not just Muslims but also the minorities living in the country. Assuring them of equal status, he said famously: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this state of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed — that has nothing to do with the business of the state.… We are starting in the days where there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle: that we are all citizens, and equal citizens, of one state.” Following this vision, the first Constituent Assembly adopted the Objectives Resolution which said that “adequate provision shall be made for the minorities to profess and practise their religions and develop their cultures.” It added that there would be “guaranteed fundamental rights, including equality of status, of opportunity and before law, social, economic and political justice, and freedom of thought, expression, belief, faith, worship and association, subject to law and public morality”. There were meant to be “adequate provisions … to safeguard the legitimate interests of minorities and backward and depressed classes”. Was it sufficient to merely pass a resolution and include the rights of minorities in the constitution while doing little to actually put such ideals into practice? What steps did the state take to make the nation aware of the rights of those who are in fewer numbers? The hard fact is that constitutions or laws cannot change societies or deliver on intentions unless they have social acceptance and the full backing of the state. This is what has led Pakistan to the current pass in terms of its minorities. The bitter reality is that the state machinery has, since its creation, miserably failed to protect minorities’ rights. While on the one hand governments have been enacting rosy-looking legislation, on the other they have failed in practice to create a consensus policy agenda on minorities’ status within Pakistan that would create a more conducive national mindset. In fact, they have remained involved in painting and treating minorities as unequal. Article 5 of the constitution states that loyalty and adherence to the constitution is the basic responsibility of every Pakistani citizen. Not only does the constitution extend equality to citizens regardless of caste or creed, under Article 36 it also imposes upon citizens and the government the responsibility of safeguarding the legitimate interests of minorities. This includes due representation in the federal and provincial services as well as social and economic justice and equality for minorities in the eyes of the law. Practically, however, minorities are disempowered. Contrary to the Quaid-i-Azam’s vision and constitutional bindings, the state has been unable to ensure minorities’ vibrant participation in state affairs. How many non-Muslims have been promoted to higher bureaucratic posts? How many non-Muslim police chiefs or chief secretaries and secretaries have there been during the past 65 years? How many members of minority communities have been inducted into the Pakistan Army and promoted to top ranks? What additional qualities do our Muslim politicians possess so that the prime minister and president of Pakistan can be chosen from amongst them, and amongst them alone? At the moment, there is not one judge from the minorities amongst the superior judiciary in any of the four provinces, the Islamabad High Court or the Supreme Court. Does Article 36 of the constitution not apply to the courts? Pakistan needs reminding that its proud judicial history includes people such as Justice A.R. Cornelius and Justice Dorab Patel. The buck doesn’t stop with the state. A lack of tolerance of other sects and belief systems has seeped into not just the minds of state functionaries, but also of private citizens. The extent to which most of the population is discriminatory towards minorities is nothing short of amazing. The electronic, print and social media, too, particularly in Urdu and the regional languages that most of the citizenry taps into, have by and large served to entrench intolerance and foment religious hatred. Cases involving minorities or religious matters, especially allegations of blasphemy, are often misreported or reported with sensationalist overtones. An issue as serious as sectarian killings is treated as newsflashes to be followed by spice-laden gossip masquerading as informed analysis. The sum effect of such influences was encapsulated in the murder in broad daylight of a governor in office by a man on his own security detail. Where does the answer lie? A reasonable place to start is the education sector: everyone should have access and the curriculum should be cleansed of anything that gives rise to prejudice against religious or other minorities. Religious and sectarian tolerance needs to be taught as a school subject and in military and judicial academies. Concurrently, Pakistan needs strict state action whenever cases of forced conversions come up and in incidents of religious and sectarian hatred. The state must adopt basic measures and teach people how to live in harmony in the true sense with people belonging to other castes and creeds.

M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

No comments:

Post a Comment