M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Saturday, May 8, 2021

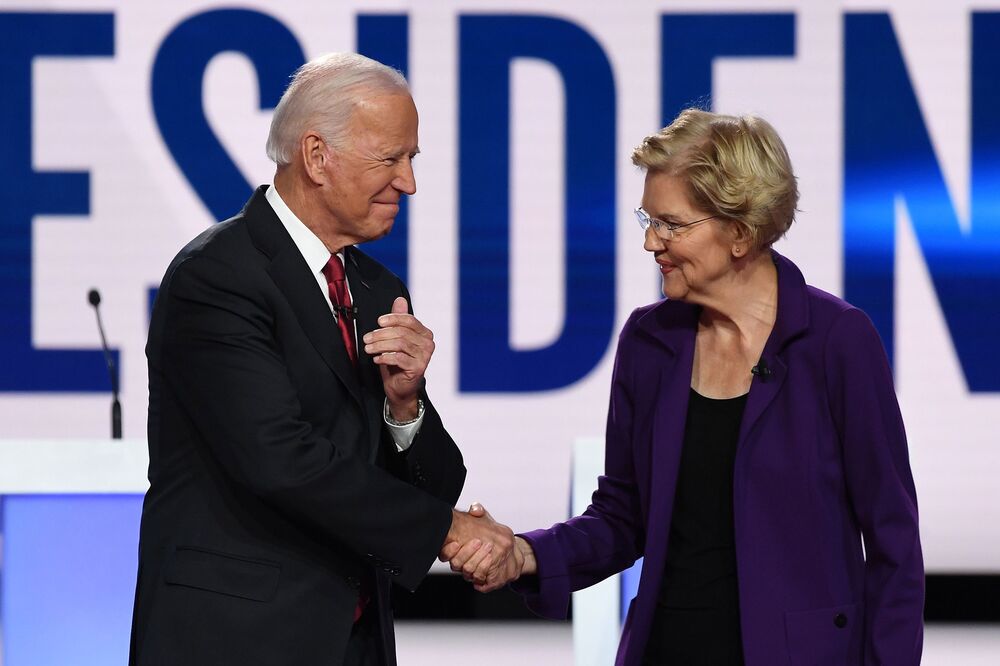

Elizabeth Warren: President Biden Is ‘Meeting The Moment’

The senator from Massachusetts said she plans to continue pressing the president to do more on child care and other issues. A few days before Sen. Elizabeth Warren dropped out of the race for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, she said that rival Joe Biden was “so eager to cut deals with Mitch McConnell and the Republicans that he’ll trade good ideas for bad ones.” More than a year later, following a coronavirus pandemic that transformed now-President Biden’s governing agenda, the senator from Massachusetts is pleasantly surprised. “He’s meeting the moment,” Warren said in an interview with HuffPost to promote her new book, “Persist.” “The door for making change has opened, just like it opened in the Great Depression, just like it opened in 2008, 2009, when we got Dodd-Frank and the [Consumer Financial Protection Bureau]. It’s not open all the way. It’s only open a little bit. “There’s no guarantee we will make big structural change, but the opportunity to do it is right in front of us,” she added, making a reference to her presidential campaign slogan. Warren was also pleased with Biden’s approach to dealing with the Republican Party, noting he was willing to pass the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan without any Republican support in Congress. “There are not very many people who ... tore up their $1,400 checks because they said, ‘Oh, it had to come through reconciliation without a single vote in Washington, D.C., from the Republicans,’” Warren said. “I think what Joe Biden is recognizing and making clear through his actions: He’s happy to do things bipartisan with the elected officials in Washington, but he is not going to fail to do what this nation needs just because Mitch McConnell folds his arms and says no.” Warren also dodged on applying some of her traditional critiques of the American political system to Biden’s administration. Mere minutes after denouncing the influence of “dark money” on the political system, she begged off a question about whether an outside group supporting Biden’s agenda, Building Back Together, should reveal its donors. “I don’t know the details about this,” she said. Still, Warren says there is room for Biden to be more aggressive. She noted the funding for his plans for universal child care and pre-kindergarten ― about $425 billion in the American Families Plan ― paled in comparison to what she had pushed during the 2020 primary. “Look, I’m just telling you I’ve done the numbers. It’s going to take about $700 billion to do high-quality available child care universal all across this country,” she said. “But the point is, we’re rowing in the same direction, and that’s what matters here. Am I going to keep pushing for more? You bet I am. I’m going to be pushing for a solution that is as big as the problem.”

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/elizabeth-warren-president-biden-meeting-the-moment_n_6095647ee4b0f73e530d1888

Treacherous Triangle: Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan After US Withdrawal

By Umair Jamal

After the last American soldier departs Afghanistan in September, India and Pakistan will be left with some very difficult, unsavory, choices. U.S. troops in Afghanistan have begun packing gear after President Joe Biden announced last month that all American troops will leave Afghanistan by September 2021, after a nearly two-decade-long military presence in the country. Defending his decision to withdraw all American troops from Afghanistan, Biden said, “With the terror threat now in many places, keeping thousands of troops grounded and concentrated in just one country and across the billions [of dollars spent] each year makes little sense to me and to our leaders.” “I am now the fourth American president to preside over an American troop presence in Afghanistan. Two Republicans. Two Democrats,” he added. “I will not pass this responsibility to a fifth.” Biden called on regional countries, particularly Pakistan, to do more to support Afghanistan. The international community, including the U.S., has often accused Pakistan of supporting militant groups in Afghanistan, including the Afghan Taliban, which have to some extent undermined Washington’s war efforts. In 2018, then U.S. President Donald Trump tweeted that Washington had “foolishly given Pakistan more than $33 billion in aid over the last 15 years,” but Islamabad had, in return, given “safe haven to the terrorists we hunt in Afghanistan, with little help.” In another speech laying out his Afghan policy, Trump singled out Pakistan, saying that the U.S. “cannot be silent about Pakistan’s safe havens for terrorist organizations.” Fearing the possibility of punitive action from the U.S. and seeing the international community’s attempt to engage the Afghan Taliban as a win for its own Afghanistan policy, Pakistan has been supporting the United States’ peace talks with the Taliban. Trump started negotiations with the Taliban in 2018, aimed at ending the 18-year-long war in Afghanistan. An agreement known as the Doha Accord was signed in early 2020 between the U.S. and Taliban that proposed a roadmap for the withdrawal of international troops from Afghanistan within 14 months and paved a way for the start of intra-Afghan negotiations. Pakistan played an important role in pushing the Taliban to sign the agreement with the U.S. “Their [Pakistan’s] support has been very important in directing the Taliban to come to negotiations and their continued support is going to be very important as we go to this difficult period of deciding [if] the Taliban [is] actually serious about this and [that] they are going to live up to their commitments,” General Kenneth McKenzie, head of U.S. Central Command told a U.S. Senate panel last year. Pakistan shares a treacherous, 2,670-kilometer border with Afghanistan. The mountainous border region has long served as a safe haven for many militant groups including the Afghan Taliban. The group ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 and offered sanctuaries to al-Qaeda. Since the early 1990s, Pakistan has supported the Taliban in Afghanistan in an attempt to push its regional security interests. Pakistan was one of the few countries that established diplomatic relations when the Taliban’s government came to power in Kabul. While the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 may have forced the Taliban out of power, the group has fought to expel international troops from Afghanistan in a bid to return to power, something that Pakistan has always wanted and supported despite international backlash. For decades, Pakistan has supported militant groups in Afghanistan rather than elected governments. This policy choice has created an image problem for Pakistan in Afghanistan and elsewhere, making Pakistan part of the problem rather than a solution. Arguably, U.S. forces’ withdrawal from Afghanistan offers Pakistan an opportunity to reorient its international image by playing a key role in encouraging regional cooperation to ensure stability in Afghanistan. The development offers Pakistan an opening to demonstrate to the international community that the country has made a clean break from its previous pattern of supporting militant groups in Afghanistan. “Pakistan will have to build trust with all Afghan ethnicities and political forces, rather than just being seen as ‘Taliban supporters’ or by many Afghans as ‘Taliban sponsors’,” Hassan Abbas, the author of “The Taliban Revival: Violence and Extremism on the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier,” told The Diplomat. Since the beginning of the peace talks three years ago, Pakistan has earned a good reputation by playing an effective role as a mediator. However, this effort on Islamabad’s part may have also exposed the limits of the country’s influence on the group. Pakistan reportedly told the Taliban recently that the group may lose its support if it doesn’t show flexibility in the ongoing peace process. “Enough is enough” were the words reportedly used by the Pakistani leadership to convey its displeasure to the Taliban. That said, Pakistan’s role in the Afghan peace process may largely become irrelevant if the anticipated volatility in Afghanistan becomes a bigger security headache for the country. Analysts warn that the U.S. troop withdrawal all but ensures heightened instability in Afghanistan – with potentially troubling security implications for Pakistan itself. “Increased instability in Afghanistan will produce spillover effects – increases in refugee flows, a more robust drug trade, the heightened risk of cross-border terrorism – that Pakistan won’t want,” Michael Kugelman, an analyst with the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C, told The Diplomat. “Another major concern for Pakistan would be that Taliban advances – and especially a Taliban takeover in Afghanistan – could galvanize Islamist terrorists in Pakistan, including an already-resurgent Pakistani Taliban. These would be very problematic scenarios for Islamabad.” Echoing Kugelman’s views, Abbas said that “any civil war in Afghanistan [following the U.S. withdrawal] will be terrible for Pakistan in terms of instability in Pakistan’s tribal belt and an opportunity for various militant groups to use war-torn areas for their activities and hiding.” Meanwhile, concerns have continued to mount about the ability of Afghan forces to hold the Taliban at bay without U.S. forces present in the country. A classified U.S. intelligence agencies assessment prepared during Trump’s time in the White House warned that Afghanistan could be taken over by the Taliban within two to three years if the U.S. leaves Afghanistan without ensuring a power-sharing deal among the warring factions in Afghanistan. If this happens and the peace process falls, Pakistan will be forced to return to its decades-old policy of supporting the Taliban. For decades, one of Pakistan’s key goals in Afghanistan has been to keep India at bay with the help of militant groups like the Afghan Taliban and the Haqqani Network. It should not come as a surprise that Pakistan has continued its support for the Taliban despite the fact that the country has paid a heavy price economically, combated militancy on its own soil, and earned bad will abroad. Islamabad should be expected to double down on its policy of supporting militant groups if the country sees other players doing the same. “Islamabad’s role in a post-withdrawal Afghanistan will depend on the status of the peace process. So long as the peace process is still happening, Pakistan will do what it can to support it – because it has a strong interest in the peace process leading to a political settlement, and because unending war could have undesirable spillover effects in Pakistan,” said Kugelman. “If the peace process collapses, Pakistan – and other regional actors – would fall back on the empowerment of proxies. Islamabad would scale up support to the Taliban to give it an upper hand against rival groups supported by the likes of India and Iran,” he added. This scenario directly threatens India’s political, security, and economic interests in Afghanistan and elsewhere. It is about time that India reorient its policies in Afghanistan, particularly its relationship with the Taliban in the wake of the U.S. forces’ withdrawal if the country wants to safeguard its interests. India has long supported the government in Kabul while distancing itself from the Taliban. From the 2001 Bonn conference, which paved the way for the formation of an interim government following the collapse of the Taliban regime up to the present day, India has continued a consistent policy of engaging with successive Afghan governments. In the 1990s, New Delhi supported the Northern Alliance against the Pakistan-supported Taliban and has continuously opposed the return of the Taliban to power in any form. The U.S. withdrawal, however, is guaranteed to make the Taliban stronger – either by giving it the upper hand in negotiations with Kabul, by giving it a major battlefield advantage, or both. The changing dynamics in Afghanistan indicate that New Delhi may be considering opening talks with the Taliban. Addressing the intra-Afghan talks last year, India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar reiterated his country’s support for an “Afghan-led, Afghan-owned, and Afghan-controlled” peace process and refrained from offering any view on the Taliban’s participation. Perhaps Washington would also like India to follow this policy approach given that the group is poised to return to power in one form or another, and India’s engagement with the Taliban can ultimately serve the United States’ interests as well. Last year, Zalmay Khalilzad, U.S. special envoy for Afghanistan reconciliation, called on India to engage with the Afghan Taliban and “directly discuss its concerns related to terrorism,” adding that Washington wants New Delhi to “take on a more active role in the Afghan peace process.” Meanwhile India maintains categorically that it will not support a Taliban government in Kabul, as was clear from a May 4 joint EU-India press statement on Afghanistan. While the Indian government is likely to be concerned about the rise in violence and the likelihood of pro-Pakistan Taliban’s return to Kabul, the country is yet to decide on the issue of engaging the Taliban. “The Indian government is likely concerned about what the withdrawal of American troops means for the political future of Afghanistan given Pakistan’s close relationship with the Afghan Taliban. A takeover by the Afghan Taliban, and Afghanistan hosting terrorist groups on its soil – especially India-focused jihadists – are India’s top concerns,” said Amira Jadoon, a professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point. However, she said there is an opportunity for India here as well. “There is evidence that Pakistani influence on the Afghan Taliban has waned over the years, as the Afghan Taliban have sought new patrons, diversified their sources of support, and gained territorial control,” Jadoon said. “If intra-Afghan talks are successful in setting up a power-sharing arrangement, then India’s relationship with the Afghan government can provide it with an opportunity to redefine its political and diplomatic engagement with Afghanistan,” added Jadoon. It is possible that the Afghan Taliban will welcome rapprochement with India for three reasons. First, India’s engagement with the Taliban offers the group greater political and diplomatic legitimacy; second, it further diversifies its international linkages; and third, it fosters the organization’s independence and makes it less reliant on Pakistan’s support or demands. “Establishing ties with Afghanistan’s most powerful non-state actor could put New Delhi in a better position to convey and negotiate its goals and interests in Afghanistan,” said Abbas. That said, New Delhi has a long road ahead of it. Pakistan will likely oppose and undermine any Indian engagement with the Afghan Taliban. Amidst this highly volatile and uncertain situation, the possibility of a proxy war between India and Pakistan in Afghanistan is very much possible. “All this said, if the peace process collapses after the U.S. withdrawal, India may find itself having to fall back on old policies by backing anti-Taliban units, such as the Northern Alliance,” said Kugelman. “So there’s a good chance that Afghanistan could once again become an India-Pakistan proxy battleground. And the stepped-up violence entailed by this would mean that the Afghan people, as always, pay the biggest price,” he added. Echoing Kugelman’s views, Abbas notes that India “is naturally worried given its strong relations with the prevailing political elite in Kabul. India has invested in Afghan reconstruction in a big way and will not be willing to allow it to be discarded.” “It will put up a fight in support of its friends leading to prospects of an intense India-Pakistan proxy war in Afghanistan,” he added. “That will be a terrible outcome, especially for Afghans.”https://thediplomat.com/2021/05/treacherous-triangle-afghanistan-india-and-pakistan-after-us-withdrawal/

Afghanistan School Bombing Targets #SHIA Minority Community - Attack on Hazara Students Highlights War’s Toll on Civilians

As Afghan peace talks crawl along in Doha, a brutal attack on a school in Kabul on Saturday underscored the terrible toll the conflict continues to take on civilians.

A massive suicide bombing on October 24 outside the Kawsar-e Danish educational center in west Kabul was the latest attack cruelly targeting the Hazara Shia minority. The explosion took place in a crowded, narrow street outside the center, killing 30 people and injuring more than 70, mostly children and young adults between 15 and 26 years old who were attending classes.

Since 2017, the Dasht-e Barchi neighborhood, home to a predominantly Hazara community, has seen numerous attacks on civilians. A bombing at the Imam Zaman mosque in October 2017 killed 39; an attack on a school in August 2018 killed more than 34 students; and twin bombings at a wrestling club in September 2018 killed 20, including journalists and first responders who arrived after the first explosion. In May, gunmen murdered 15 women in the maternity wing of the Dasht-e Barchi hospital, many of whom were in labor or had just given birth.

The Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP), the Afghan branch of the Islamic State (ISIS), claimed responsibility for Saturday’s attack. The armed group has claimed responsibility for many such bombings and has long singled out Afghanistan’s Hazara Shia community for attack. Intentional attacks on civilians are grave violations of the laws of war, and those responsible should be prosecuted for war crimes.

Many mosques and educational facilities in Kabul now have armed guards, but this offers little protection from such calculated attacks. Afghan authorities repeatedly promise investigations, including tasking the attorney general’s war crimes unit to carry them out, but none have yielded results, leaving family members of victims with neither answers nor justice.

“They are killing our youth,” said the relative of one of the victims of Saturday’s attack. The students, many from poor families who, as one of their teachers said, had come to Kabul in hope “for a brighter future.” On Sunday they were buried.

https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/26/afghanistan-school-bombing-targets-minority-community#

#Pakistan - #NA-249 recount finds #PPP victor by greater margin

https://www.geo.tv/latest/349387-na-249-recount-finds-ppp-victor-by-greater-margin

UK variant accounts for 70% of COVID cases in Pakistan -researcher

Syed Raza HassanA coronavirus variant first discovered in the United Kingdom now accounts for up to 70% of COVID-19 infections across Pakistan, a research centre studying the disease in the country said on Saturday.The country has imposed strict nationwide restrictions in the lead up to the Muslim festival of Eid al-Fitr next week in a bid to control a spike in cases, including banning public transport over the holiday period. "There is a 60% to 70% prevalence of the UK variant in Pakistan (today)," Professor Dr Muhammad Iqbal Chaudhry, director at the International Centre for Chemical and Biological Sciences (ICCBS), University of Karachi, told Reuters, adding that this figure was 2% in January. The ICCBS works on COVID-19 samples and provides research and data to the government. The "UK variant", known as B.1.1.7 and first identified in Britain late last year, is believed to be more transmissible than other previously dominant coronavirus variants. Chaudhry added, however, that it was yet to be established if the variant was more deadly. He also said a variant found in neighbouring India, which has seen a massive surge of cases in recent weeks, had not been detected in Pakistan yet, but that was because they did not have the kits needed to detect the variant, named B.1.617. The kits to detect the variant had been ordered and would soon arrive in the country, he said. Chaudhry said there was a high possibility that the variant had already reached Pakistan since the diasporas of the two countries interact closely in Gulf states. Pakistan has seen a daily death toll of more than 100 in recent weeks. Officials are worried the strained healthcare system could reach a breaking point if more contagious coronavirus variants begin to spread, as has happened in India. Overall, Pakistan has registered 854,240 infections and 18,797 deaths from COVID-19. While official daily infection numbers remain low, between 4,000 and 5,000, the country conducts only around 40,000 tests a day - a fraction of its 220 million population. The country has recently stepped up its vaccination drive, inoculating around 3.3 million people. On Saturday it received its first batch of 1.2 million vaccine doses under its COVAX.

https://news.yahoo.com/uk-variant-accounts-70-covid-141529533.html