M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Wednesday, November 18, 2020

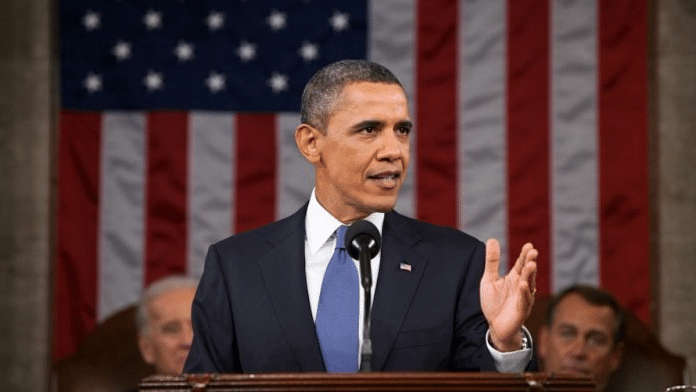

Elements inside Pakistan military had links to al-Qaeda — Obama on raid that killed Osama

In his book, Barack Obama described the various options of killing Osama bin Laden once it became clear that he was living in a safe hideout on the outskirts of Abbottabad.

Barack Obama has said that he had ruled out involving Pakistan in the raid on Osama bin Laden’s hideout because it was an “open secret” that certain elements inside Pakistan’s military, and especially its intelligence services, maintained links to the Taliban and perhaps even al-Qaeda, sometimes using them as strategic assets against Afghanistan and India.

Giving a blow-by-blow account of the Abbottabad raid by American commandos that killed the world’s most wanted terrorist on May 2, 2011 in his latest book “A Promised Land”, the former US president said that the top secret operation was opposed by the then defence secretary Robert Gates and his former vice president Joe Biden, who is now the President-elect.

In the book that hit the stands globally on Tuesday, America’s first Black president described the various options of killing bin Laden once it became increasingly clear that the elusive al Qaeda chief was living in a safe hideout on the outskirts of a Pakistani military cantonment in Abbottabad.

Based on what I’d heard, I decided we had enough information to begin developing options for an attack on the compound. While the CIA team continued to work on identifying the Pacer, I asked Tom Donilon and John Brennan to explore what a raid would look like, Obama writes in his memoir.

The need for secrecy added to the challenge; if even the slightest hint of our lead on bin Laden leaked, we knew our opportunity would be lost. As a result, only a handful of people across the entire federal government were read into the planning phase of the operation, he said.

We had one other constraint: Whatever option we chose could not involve the Pakistanis, he wrote.

Although Pakistan’s government cooperated with us on a host of counterterrorism operations and provided a vital supply path for our forces in Afghanistan, it was an open secret that certain elements inside the country’s military, and especially its intelligence services, maintained links to the Taliban and perhaps even al-Qaeda, sometimes using them as strategic assets to ensure that the Afghan government remained weak and unable to align itself with Pakistan’s number one rival, India, Obama revealed.

The fact that the Abbottabad compound was just a few miles from the Pakistan military’s equivalent of West Point only heightened the possibility that anything we told the Pakistanis could end up tipping off our target.

“Whatever we chose to do in Abbottabad, then, would involve violating the territory of a putative ally in the most egregious way possible, short of war raising both the diplomatic stakes and the operational complexities, he wrote.

In the final stages they were discussing two options. The first was to demolish it with an air strike. The second option was to authorise a special ops mission, in which a select team would covertly fly into Pakistan via helicopter, raid the compound, and get out before the Pakistani police or military had time to react.

Despite all the risks involved, Obama and his national security team opted for the second option, but not before multiple rounds of discussions and intensive planning.

The day before he gave the final approval for the raid, at a Situation Room meeting, Hillary Clinton, the then Secretary of State, said that it was a 51-49 call. Gates recommended against a raid, although he was open to considering the strike option, he said.

Joe (Biden) also weighed in against the raid, arguing that given the enormous consequences of failure, I should defer any decision until the intelligence community was more certain that bin Laden was in the compound.

“As had been true in every major decision I’d made as president, I appreciated Joe’s willingness to buck the prevailing mood and ask tough questions, often in the interest of giving me the space I needed for my own internal deliberations, Obama wrote.

After the successful Abbottabad raid, Obama made a number of calls domestically and internationally, the toughest of which he expected to be that with the then Pakistan President Asif Ali Zardari, he wrote.

I expected my most difficult call to be with Pakistan’s beleaguered president, Asif Ali Zardari, who would surely face a backlash at home over our violation of Pakistani sovereignty. When I reached him, however, he expressed congratulations and support. ‘Whatever the fallout,’ he said, ‘it’s very good news. He showed genuine emotion, recalling how his wife, Benazir Bhutto, had been killed by extremists with reported ties to al-Qaeda, Obama wrote.

Mike Mullen had put a call in to Pakistan’s army chief, General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, and while the conversation had been polite, Kayani had requested that we come clean on the raid and its target as quickly as possible in order to help his people manage the reaction of the Pakistani public, he said.

Laden, the world’s most wanted terrorist, was the chief of al-Qaeda that carried out the 9/11 attacks on twin towers in New York, killing nearly 3,000 people. He was killed in a covert raid by a US Navy SEAL team at his Abbottabad compound in Pakistan.

https://theprint.in/world/elements-inside-pakistan-military-had-links-to-al-qaeda-obama-on-raid-that-killed-osama/546029/

An Excerpt: ‘The Nine Lives of Pakistan: Dispatches From a Precarious State,’ by Declan Walsh

Insha’Allah Nation

Land of Broken Maps

In the summer of 2004, I drove from my new home in Islamabad to the dowdy garrison city of Rawalpindi, about fifteen miles away. The road led down a chaotic, fume-choked highway where tiny yellow taxis weaved around hulking rainbow-coloured trucks, their flanks painted with delicate floral motifs. After passing the army’s General Headquarters, I turned onto a quieter road and pulled up outside a quaint-looking, Victorian-era building. A pungent odour of brewing hops wafted through the air. The owner waited inside.

Minoo Bhandara perched behind an antique desk in a dimly lit office, resplendent in a three-piece suit despite the hundred-degree weather outside. He was in his sixties, a portly man with tinted glasses and a vaguely impish smile. A fan whirred overhead. ‘I’ll be with you in a minute,’ he said, signing some papers. The walls were lined with framed antique cartoons that depicted pearl-skinned British soldiers in battle, firing at wild-eyed tribesmen or spearing them with bayonets – century-old company calendars. The Murree Brewery had been founded in 1861 to slake the thirst of the soldiers of the Raj, as British rule in colonial India was known. Now it was listed on Pakistan’s stock exchange. ‘We’re one of the country’s biggest taxpayers,’ Bhandara boasted.

His success was puzzling. Prohibition had been in effect in Pakistan for a quarter-century, and any Muslim caught slugging one of Bhandara’s lagers could be sentenced to eighty lashes from an oil-soaked whip. Yet Murree Brewery was doing a roaring trade, largely on the back of sales to God-fearing Muslims, Bhandara cheerfully admitted. Trade was so strong, in fact, that the company was expanding into foreign markets. A new line of single-malt whisky was being casked in the cellar; ‘Have a Murree with Your Curry’ was the marketing slogan in Britain.

I’d been in Pakistan a month or so by then, and the breakfast beer would prove the first of numerous riddles in the country. At that point, though, I was struggling to warm to my new assignment. Islamabad seemed dull and bloodless, a shimmering monotone of broad avenues and gaudy mansions. It was a chessboard capital, a low suburban sprawl that was divided into square neighbourhoods named after grid references or primary colours. My guesthouse was in F-7/3; the sleepy main shopping drag was the ‘Blue Area’. Houses were built in a bewildering range of styles – imperial Rome, Spanish hacienda, seventies chic. Public monuments included a replica of the mountain where Pakistan exploded its first nuclear device in 1998, and replica missiles that appeared to be pointed in the direction of the Indian border. At night, rich kids drag-raced their fathers’ saloon cars under the Margalla Hills, swerving to avoid the wild hogs that ambled from the bushes. Getting a drink involved ridiculous subterfuge. ‘Special tea, sir?’ the waiters at the Marriott hotel would ask archly, proffering a teapot filled with bootleg Chianti.

Pakistanis from more spirited cities sneered at Islamabad’s antiseptic calm. ‘Don’t tell me that you live in that Hicksville,’ a peroxide-haired fashionista told me in Karachi. Westerners took a perverse pleasure in the capital’s isolation from the chaotic country it ruled. ‘Islamabad: only half an hour from Pakistan,’ diplomats would quip at stuffy parties where gloved attendants served gin-and-tonics on the terrace.

The torpor of Islamabad mirrored the wider mood of the country, then in the grip of its fourth bout of military rule. The generals had ruled directly for half of Pakistan’s history since independence in 1947, always seizing power with an air of feigned reluctance. The civilians had screwed things up again, they would mutter – time for a stiff dose of military discipline to set things right. The latest khaki messiah was Pervez Musharraf, the army chief who had ousted Nawaz Sharif five years earlier. A photo of Musharraf, broadcast on state TV in the early hours of the coup, was unpromising: a macho-looking officer in fatigues and brandishing a pistol, with a cigarette dangling from his lips. But Pakistanis quickly warmed to him. In contrast with Sharif, who had become erratic and autocratic in power, Musharraf turned out to have an endearing manner and a caddish charm. He played golf and tennis, smoked cigars, and sat in the front row of fashion shows where he flashed a cheeky smile at the models. He gave himself the title of ‘chief executive’ and made extravagant promises of eradicating corruption. At an early press conference, Musharraf posed for the cameras with his wife, his mother and his Pekinese dogs, Dot and Buddy – an image that enraged conservative clerics, who were unsure whether they hated dogs or women more, and delighted just about everyone else. Meanwhile, Sharif was taken to a remote fortress over the River Indus, stripped of property worth $8 million and later dispatched into exile at a palace in Saudi Arabia.

By the time I reached Pakistan, in 2004, the Musharraf magic was fading. The military leader had organised a referendum on his popularity that was supposedly approved by 98 per cent of voters, followed by an election that the ISI tilted in his favour. People grumbled, but it was too late. Parliament had been reduced to a toothless talking shop, stuffed with cronies and sycophants, and Musharraf’s political rivals languished in exile – a state of affairs that suited the Americans justfine.

The United States and Pakistan had been feuding and falling in love for decades. People often compared their tempestuous, co-dependent relationship to a bad marriage, but it was more accurately the worst kind of forced marriage – a product of shared interests rather than values, devoid of genuine affection and scarred by a history of dispute and betrayal. It started during the Cold War, in the 1950s, when the Americans ran a secret base in Peshawar from which Gary Powers, the pilot of a U-2 spy plane, took off before being shot down over the Soviet Union in 1960. The two countries forged a momentous partnership in the 1980s to expel the Soviets from Afghanistan, declaring victory in 1989. But barely a year later Washington slapped painful sanctions on Pakistan over its covert nuclear weapons programme. Stung, the Pakistanis made crude jokes about being treated like a used condom, and then eight years later exploded a nuclear bomb anyway. The September 2001 attacks on America threw them together again. President George W. Bush needed Pakistan’s help with the war in Afghanistan – American supply lines ran through Karachi – and with the hunt for the fugitive Osama bin Laden, who, as far as anyone could tell, had slipped into Pakistan’s tribal areas. Bush hailed Musharraf as his ‘buddy’ and lavished him with F-16 warplanes and billions of dollars in aid. The Pakistani leader reciprocated with terrorist scalps: Pakistan’s intelligence services rounded up hundreds of al Qaeda suspects and shipped them to Guantánamo Bay and CIA ‘black sites’ – secret prisons in Poland, Thailand and Afghanistan – where many were tortured. Grateful American officials heaped praise on Musharraf’s ‘controlled democracy’. ‘You have to realise,’ one State Department official told me over beers in his Islamabad garden, ‘that this is the best we can hope for.’ He didn’t even have the decency to blush.

Pakistan’s relations with India, meanwhile, bobbed along at a low ebb. A few years earlier, the two countries had flirted with mutual annihilation when an attack by Pakistan-backed militants against India’s Parliament building caused the mobilisation of one million soldiers in both countries, raising the possibility of a nuclear war. Now they were back to more mundane tit-for-tat. An Indian diplomat invited me for Sunday brunch at her home. I arrived to find her standing at the door, sheened with sweat and proffering apologies. The electricity had been cut off, most likely by the Pakistani spooks who harassed the other guests as they arrived, and there was no air-conditioning. The diplomat shrugged. ‘Don’t worry,’ she said nonchalantly. ‘We do the same to their people in New Delhi.’

Pakistan was once a hopeful prospect of the post-colonial world. In the 1960s, when its economy was on a par with Singapore’s, cheering throngs greeted the American president, Dwight Eisenhower, as he toured Karachi in an open-top limousine. Jackie Kennedy visited in 1963, jaunting around the garden of the military ruler, Field Marshal Ayub Khan, on the back of a camel. Indians, whose leaders were closer to the Soviet Union, laboured under a suffocating bureaucracy and a socialist economy; Pakistanis had Coca-Cola, imported Toyotas, and a modern new capital. But disaster struck in 1965 in the form of a misbegotten war with India, triggered by Pakistani attempts to instigate a revolt in the disputed territory of Kashmir. Pakistan lost, and the mishaps kept piling up: assassinations, insurgencies, more military coups, and, through the 1980s, an influx of guns, narcotics and refugees from war-torn Afghanistan.

The greatest calamity by far occurred in 1971, with the secession of East Pakistan. The country was an oddly shaped entity from its birth, composed of two ‘wings’ – East Pakistan, on the Bay of Bengal, and West Pakistan, centred on Karachi and Lahore – that were separated by a thousand miles of hostile Indian territory. The awkward arrangement was exacerbated by discrimination and racism. The East Pakistanis were poorer and more dark-skinned than their Western cousins, who disregarded the Bengalis’ language and treated them with condescension. The inevitable uprising, following an election in 1970, met with a brutal response. Pakistan’s army, aided by Islamist militias, massacred Bengali villagers, executed intellectuals and raped an untold number of women. American diplomats warned privately of ‘selective genocide’, but the Nixon administration, mindful of its alliance with Pakistan, turned a blind eye to the atrocities. India sided with the Bengali rebels, decisively tipping the military balance, and in December 1971, Pakistan’s generals submitted to a humiliating surrender. War Till Victory read the headline in Dawn. East Pakistan became Bangladesh.

It was a devastating blow – not only because the Bengalis accounted for half of Pakistan’s population and held one-third of its territory, but because their departure had shattered a foundational myth: that Pakistan was the sole homeland for the Muslims of SouthAsia.

After 2001, when the attacks on America thrust Pakistan to global prominence, the country occupied an uncomfortable place in the Western imagination, as a crucial yet perfidious ally. Daniel Pearl of the Wall Street Journal was kidnapped from Karachi in 2002 and beheaded nine days later. News stories were invariably accompanied by photographs of rabid-looking clerics torching American flags. Successive opinion polls ranked it among the least popular countries on Earth. If Pakistan was a person, Christopher Hitchens wrote, he would be ‘humourless, paranoid, insecure, eager to take offence and suffering from self-righteousness, self-pity and self-hatred’; Thomas Friedman of the New York Times, visiting Peshawar, complained of ‘cold stares and steely eyes’.

‘Those eyes did not say, “American Express accepted here”,’ Friedman wrote. ‘They said, “Get lost.”’

Once I had settled in, though, a more complex and interesting country came into view, softer around the edges than its dour image suggested, where people loved to let their hair down.

An early revelation was Basant, Lahore’s spectacular spring fiesta. Kites filled the skies over the Old City, where giddy boys coursed through the narrow streets, in the shadow of the ancient Lahore Fort, tugging on strings as they did battle in the sky. On the rooftops, I mingled with city grandees who chewed kebabs at lavish parties in traditional haveli mansions. The forbidden pleasures were at street level. One night I attended a rave party at an abandoned bakery, where young Pakistanis high on the drug Ecstasy bopped to a throbbing techno beat. Another time, I ended up at a party hosted by an underground gay collective. Hot Boyz read the sign on the door. Outside, several hundred men danced to the top Bollywood hits, some in dresses and lipstick, others with heavy moustaches. I lingered awkwardly on the edge of the crowd, until a man in a sequinned dress – a hijra, as Pakistan’s third sex are known, who make money dancing at weddings or begging in traffic – beckoned me onto the floor.

Pak is the Urdu word for ‘clean’, so Pakistan translates literally as ‘Land of the Pure’. But the pockets of permissiveness, at odds with the country’s reputation, weren’t limited to the party scene. I visited art exhibitions that explored Islamist violence or the intimacies of the heart. In the countryside, I visited religious shrines where Hindus and Muslims worshipped side by side in a tradition that stretched back centuries. Climbing to a remote valley in the Hindu Kush, I met the Kalash, a tiny tribe of animist believers supposedly descended from Alexander the Great, who carefully guarded their traditions.

My story on the Murree Brewery was a cliché of foreign correspondence – nearly every newly arrived reporter had covered it – but the company’s unlikely success spoke to a broader truth about Pakistan. Despite its harsh Islamic laws, every neighbourhood had a semi-official bootlegger, which made it as easy to order a bottle of whisky as a pizza. (The whisky usually arrived more quickly.) Newspapers carried advertisements for clinics that treated alcoholism. Nobody had been lashed with an oil-soaked whip for decades. At Murree Brewery, Minoo Bhandara led me to a first-floor window where he pointed to a grand, white-columned house across the street: the residence of President Musharraf who, it was widely known, was partial to a dose of Johnnie Walker premium blend Blue Label in the evening.

I rented a house on the Islamabad chessboard, a four-bedroom villa with a capacious garden, bought a 1967 Volkswagen Beetle (of a marque known to Pakistanis as a ‘Foxy’) for scooting around the city, and acquired three dogs, all strays. Spike and Luna came via friends; Pookie straggled through the front gate as a puppy. When I told a visiting American diplomat, who was versed in the ways of the intelligence world, that Pookie was a ‘walk-in’, he shot back: ‘Well, I hope she brought some useful information.’

I hired a housekeeper named Mazloom Raja, a gentle man in his fifties with speckled hair that he frequently dyed black, in the style of Musharraf. Mazloom meant ‘The Suffering One’, which was apt. He seemed weighed down by the tribulations of a working-class life: squabbling relatives, scheming young men seeking to bed his daughter and regular attendance at funerals for unfortunate relatives struck down by disease or accidents. When I was out, I realised, he sneaked into the TV room to catch up on Bollywood movies. He could be excessively deferential. When Mazloom started to call me ‘sir’, I asked him to use my name. He shuffled awkwardly.

‘Yes, sir,’ he replied.

Autumn arrived, and with it Ramzan, as Pakistanis and Indians call the Muslim holy month of fasting and prayer. Pakistanis advertised their piety with long faces during the day, when restaurants were closed, and donned their finest duds at night, when they gorged on rich food and socialised until it was time for suhoor, the predawn breakfast. As my car idled at a traffic light, a young man on a bicycle – a student at a madrassa religious seminary, judging from his wiry beard and hitched trousers – rapped on the window of my Beetle and proceeded to admonish me for chewing gum. I told him I was a Christian. No matter, he shot back testily. ‘Pakistan is a Muslim country.’ A rule was a rule.

Or was it? The country’s most notorious madrassa was the Darul Uloom Haqqania, a vast complex near Peshawar whose 4,000 students were taught a harsh, fundamentalist brand of Islam. In the 1980s, when the madrassa churned out radicalised students who later crossed the border to fight in Afghanistan, it was informally known as the ‘University of Jihad’. Its head was a stern, henna-bearded cleric who liked to claim that his students included the Afghan Taliban’s top leaders. But he also had his mortal weaknesses. I heard accounts that, some years earlier, the Pakistani intelligence services had caught the cleric on camera at an Islamabad brothel with two other people, at least one of whom was a prostitute. Subsequently, the cleric, Maulana Sami ul Haq, was informally known in political and media circles as ‘Sami the sandwich’.

In Pakistan, it seemed, prose could be as rich as poetry. Novelists such as Mohammed Hanif, Mohsin Hamid and Kamila Shamsie were gaining global acclaim for their artful depictions of the country. But daily life offered the best material. ‘We have no need for magic realism,’ a lawyer friend told me. ‘We just have realism.’

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/17/books/review/the-nine-lives-of-pakistan-dispatches-from-a-precarious-state-by-declan-walsh-an-excerpt.html

He Reported on Pakistan’s Volatile Politics. Then He Became a Story Himself. ''THE NINE LIVES OF PAKISTAN''

By Amna NawazTHE NINE LIVES OF PAKISTAN Dispatches From a Precarious State By Declan Walsh The question has confounded many: How does Pakistan stay alive? The 73-year-old nation born of a bitter postcolonial divorce has heaved through humiliating defeats, careened from coup to coup and stubbornly endured despite relentless forces working to unweave it. How? The New York Times foreign correspondent Declan Walsh is the latest to try to answer that question. In his new book, “The Nine Lives of Pakistan: Dispatches From a Precarious State,” he pulls from years of contact with sources on the ground, presenting nine narratives — each given its own chapter — to paint a vivid, complex portrait of a country at a crossroads. This nuclear-armed nation is today the fifth most populous in the world. Its subcontinental perch grants it strategic geopolitical importance. And though its past wars with India seem to consume Pakistan’s almighty army leaders, for the past two decades it’s largely been America’s war in neighboring Afghanistan that’s demanded their attention.

Walsh spent nearly a decade living in and covering Pakistan, first for The Guardian, then for The Times. His tenure coincided with some of the country’s most turbulent modern years: fraught elections, assassinations and military rule; a war next door and within; and a tenuous alliance with the United States fraying to the breaking point, particularly after American Special Forces found Osama bin Laden hiding inside Pakistan, and killed him.During Walsh’s years in Pakistan, he produced news story after news story, until, in 2013, he became one himself. He was unceremoniously kicked out of the country by the government, presented the decision by police officers who showed up at his Islamabad home in the middle of the night. Among the group was a bearded man in civilian clothes, who handed him an envelope marked “By Special Messenger,” containing a letter giving him 72 hours to leave. “The Special Messenger,” Walsh writes, “flashed me an awkward smile and then, in the finest tradition of subcontinental bureaucracy, politely asked me to sign for my own expulsion order.” It’s here that Walsh begins his book, with his own departure, a personal mystery that needs solving: What was it about his work that led the authorities to throw him out?

Most of the “nine lives” he goes on to profile were previously subjects of Walsh’s reporting. The two exceptions are an intelligence source he tracks down to try to understand his expulsion, and the country’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Jinnah is Pakistan’s original enigma: a thoroughly westernized, secular barrister who fought for a Muslim homeland after Partition. Walsh offers Jinnah’s vision of what Pakistan could be — a nation of faith, unity and discipline — and then proceeds to document just how far from that vision it has moved.Walsh’s writing is elegant and expressive. It does what the best foreign correspondence should: transport the reader. Chaudhry Aslam, a Karachi policeman profiled in 2011 by Walsh as “Pakistan’s toughest cop,” along with the teeming city of 20 million he policed, takes robust form through Walsh’s words. He writes of the city at night after “the last rickshaws skittered home along streets bathed in flickering amber light” and of Aslam’s office, which “had the gleam of a mortuary and the furtive bustle of a mobster’s den.” In Lahore, Asma Jahangir, a diminutive human rights lawyer with a reputation for speaking unvarnished truth to power, comes alive through Walsh’s precise, observational reporting, her “rapid-fire sentences flicking between plain English and legalese as she pulled on beedis — thin, hand-rolled cigarettes of a kind typically used by poor Pakistanis.” Deep in the restive Balochistan Province, home to a separatist movement that still bedevils Pakistan’s powerful military, Walsh introduces us to a local chieftain, Nawab Akbar Shahbaz Khan Bugti — “a tribal aesthete, poetry lover and insufferable snob,” who, “in this lost corner of Pakistan … was as close to a deity as you could get.” War is a constant. Aslam’s war against surging Taliban forces in Karachi. Jahangir’s war against the powerful elite. Bugti’s war against Pakistan’s military (and the army’s brutal campaign to stop it). Every character is fighting on his or her own front line in some way. But a nation is surely more than the wars it fights, and the focus on these particular voices presents a somewhat limited picture. The selection of overwhelmingly male subjects, most of them in positions of relative privilege and power, further narrows the scope. Pakistan is a country of more than 200 million people. Nearly half are female. By some estimates, almost one-quarter of Pakistanis live in poverty. Except for Jahangir, no woman is given more than a supporting role in the book, and the poor remain largely in the background. Even the chapter featuring the story of Asia Bibi — a Christian woman who is sentenced to hang for blasphemy, and, after international outrage, later acquitted by the Supreme Court — is told through the lens of a man, Salmaan Taseer, Punjab’s governor, who was murdered by one of his own guards for demanding justice for Bibi. Walsh beautifully braids in brief history lessons, placing each voice in proper context and feeding a richer understanding for readers coming to the region fresh. To grasp the layered vista on which Aslam operates, Walsh traces Karachi’s growth from quiet backwater to megacity over a full century. He journeys to Punjab Province’s 17th-century Mughal roots before unfurling Jahangir’s fight for justice today. And before diving into Bugti’s battles, he gives us the story of the Balochs’ 12th-century migration and the generations of uprisings that followed. Peppered throughout are reminders that this work is not easy. It is telling that among the nine profiled in the book, only one subject remains alive; more than half were killed. Walsh functions with the assumption that his lines are tapped, works to avoid intelligence tails and continues to pry into the dark corners that those in power wish he wouldn’t. Eventually it is that prying that puts him in the cross hairs of Pakistan’s leaders. A supplicant civilian government can’t save him. Diplomatic entreaties fail. The military and its intelligence arm flex their muscles, flick their wrists and have Walsh removed, after a much longer stint than many foreign correspondents in Pakistan. That investment on the ground is apparent in his book. Despite the fighting, the uncertainty and the sheer degree of difficulty involved in reporting in Pakistan, his familiarity with and fondness for the people and places he covers is clear. Even after he is kicked out, he unsuccessfully petitions officials overseas for one last chance to return: “If nothing else, I wanted closure, an opportunity to say farewell to the country that filled my life for a decade.”