M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Monday, July 1, 2019

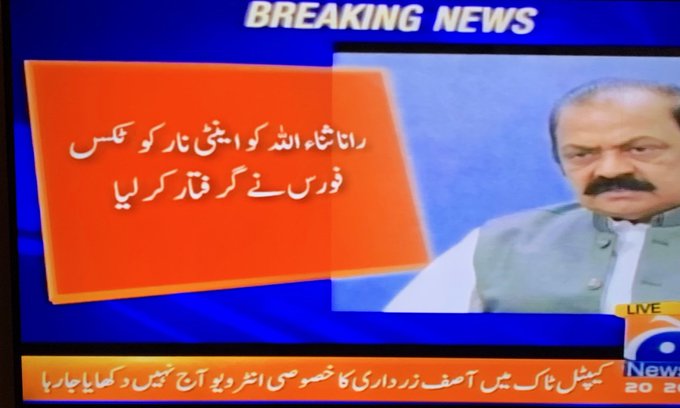

سابق صدر آصف زرداری کا ٹی وی انٹرویو کس نے روکا؟

جیو نیوز کے پروگرام ’کیپیٹل ٹاک‘ کے میزبان حامد میر نے کہا کہ جنہوں نے انٹرویو رکوایا ہے ان میں ہمت نہیں کہ وہ سر عام اس بات کا اعتراف کر سکیں۔

سینیئر صحافی اور جیو ٹی وی کے پروگرام ’کیپیٹل ٹاک‘ کے میزبان حامد میر نے ٹویٹ کیا ہے کہ ان کا پروگرام، جس میں انہوں نے سابق صدر آصف علی زرداری کا انٹرویو کیا تھا، اسے رکوا دیا گیا ہے۔

ٹویٹ میں انہوں نے مزید کہا کہ ’جس نے پروگرام رکوایا ہے ان میں ہمت نہیں کہ وہ سر عام اس بات کا اعتراف کر سکیں۔‘

Interview of Asif Zardari stopped on Geo News within few minutes those who stopped it have no courage to accept publically that they stopped it

4,804 people are talking about this

ایک اور ٹویٹ میں انہوں نے کہا کہ یہ سمجھنا مشکل نہیں کہ کس نے پروگرام رکوایا ہے۔ ’ہم آزاد ملک میں نہیں رہ رہے۔‘

I can only say sorry to my viewers that an interview was started and stopped on Geo New I will share the details soon but it’s easy to understand who stopped it?We are not living in a free country

8,092 people are talking about this

انڈپینڈنٹ اردو نے جب جیو ٹی وی کی انتظامیہ سے رابطہ کرنے کی کوشش کی اور پوچھا کہ جیو اس معاملے پر اپنا ردعمل دینا چاہتا ہے تو انتظامیہ کے اہم رکن کی جانب سے نام ظاہر نہ کرنے کی شرط پر کہا گیا کہ اس معاملے پر ’اگر ردعمل دے سکتے تو انٹرویو نہ چلا دیتے۔‘ انہوں نے مزید کہا کہ ’وہ اس معاملے پر بولنا چاہتے ہیں مگر وہ نہیں چاہتے کہ ان کی وجہ سے ان کے ادارے کا کوئی نقصان ہو۔‘

پیپلز پارٹی پنجاب کے جنرل سیکرٹری چوہدری منظور نے انڈپینڈنٹ اردو سے بات کرتے ہوئے کہا ’دنیا میں کبھی ایسا ہوا ہے کہ ایک شو جو کہ ریکارڈ ہوا ہو اور جس کے ٹکرز چلے ہوں اسے ایک دم بند کر دیا جائے؟‘

جب ان سے پوچھا گیا کہ ان کے خیال میں پروگرام کو رکوانے کے پیچھے کون ہے تو ان کا کہنا تھا کہ پروگرام ’حکومت نے رکوایا اور حکومت کے ماتحت اداروں نے رکوایا۔‘

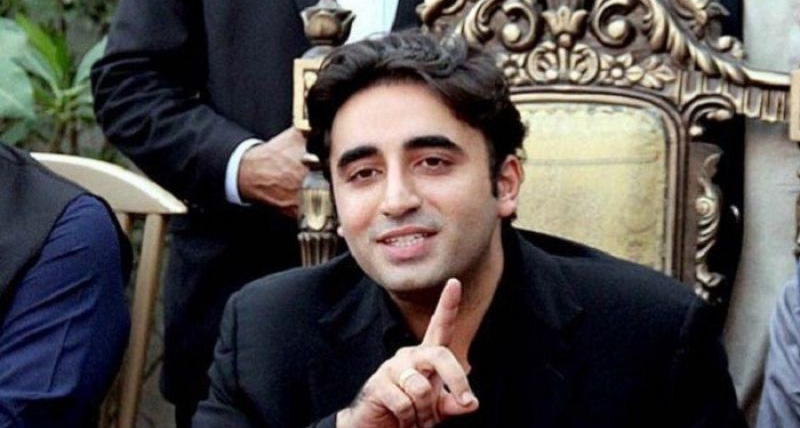

چیئرمین پیپلز پارٹی بلاول بھٹو زرداری نے اسی معاملے پر ٹویٹ کیا اور کہا کہ ’سلیکٹڈ حکومت صرف سلیکٹڈ آوازیں سننا چاہتی ہے۔‘

Selected government only wants to hear selected voices. President Zardari’s interview with @HamidMirPAK censored. Pulled from air when it had already started. No difference in Zias Pakistan, Musharrafs Pakistan & NayaPakistan. This is no longer the free country Quaid promised us.

3,086 people are talking about this

الیکٹرانک میڈیا کو ریگولیٹ کرنے والی اتھارٹی پیمرا کے جنرل مینیجر فخرالدین مغل سے جب انڈپینڈنٹ اردو نے رابطہ کیا تو ان کا کہنا تھا کہ پیمرا کو اس بارے میں علم نہیں ہے اور اگر پروگرام رکا ہے تو چینل کی انتظامیہ نے خود روکا ہو گا۔ انہوں نے کہا، ’پیمرا جب بھی کوئی مواد روکتا ہے تو تحریری طور پر روکتا ہے۔‘

انڈپینڈنٹ اردو نے وزیراعظم کی مشیر برائے اطلاعات و نشریات ڈاکٹر فردوس عاشق اعوان اور وزیراعظم کے معاون خصوصی برائے میڈیا افتخار درانی سے حکومتی موقف جاننے کی کوشش کی مگر ان کی طرف سے کوئی جواب موصول نہیں ہوا۔

سینیئر صحافی روؑف کلاسرا نے اس معاملے پر ٹویٹ کیا اور کہا کہ ’ایسا صرف پاکستان میں ہوتا ہے کہ نیب کی حراست میں اور جسمانی ریمانڈ پر ملزم ٹی وی پر آتا ہے اور جمہوریت اور شفافیت پر درس دیتا ہے۔‘

No offences pls but no where a top accused of money laundering,frauds & fake accounts is allowed one hour air time to justify his crimes. It only happens in Pakistan where an accused in custody of NAB on physical remand,appears on tv to give us lecture on democracy& transparency https://twitter.com/hamidmirpak/status/1145715761425633285 …

3,906 people are talking about this

رؤف کلاسرا کی ٹویٹ کے جواب میں حامد میر کا کہنا تھا کہ دنیا میں ایسا بھی کہیں نہیں ہوتا کہ ایک دہشت گرد کو ریاست کا شاہی مہمان بنایا جایا۔

No offences please but no where in the world a top terrorist becomes a royal guest of state and you know who is that?He is Ehasanullah Ehsan who accepted responsibility of planting bomb under my car he gave TV interviews in “official custody” Zardari spoke to me in Parliament https://twitter.com/klasrarauf/status/1145724150612467718 …

2,053 people are talking about this

Opinion Why Can’t Pakistan Afford to Ban Indian Movies?

By Mazhar Zaidi

The terrible costs of the conflict between India and Pakistan — regional instability, militarization and economic disruption — make global headlines. But there is a largely ignored victim of the crisis: the movie business in Pakistan. There is a long history of politics hurting Pakistani cinema but a major recent blow came in Sept. 2016, when militants attacked an Indian army base in the disputed region of Kashmir, killing 19 soldiers. India blamed Jaish-e-Muhammad, a militant group based in Pakistan, for the attack. Tensions between the two countries rose. As nationalist emotions soared, an association of Indian movie producers banned Pakistani artists from working on Indian films. In Pakistan, theater owners decided not to screen Indian movies. Within three months, seat occupancy in theaters fell to 11 percent.

The immensely popular world of cinema became a space for competing, aggressive nationalism, although trade between India and Pakistan continued. Cinema has kept alive a cultural affinity in South Asia: Generations of Pakistanis have grown up watching Indian films, which are hugely popular and draw large crowds. The stars of Indian cinema — from Dilip Kumar in the 1950s to Shah Rukh Khan, the current Bollywood superstar — are widely loved. Despite numerous efforts to introduce movies from other cultures, including dubbed versions of Turkish films, Bollywood remains the primary choice for moviegoers in Pakistan. The loss of Indian movies stung so hard because Pakistan was not yet able to produce and distribute enough movies to fill theaters every week. Though the number of screens in Pakistan increased from 30 in 2013 to almost 100 in 2017, producers and investors were being cautious. And most filmmakers realized that reaching larger audiences wasn’t possible.

A few months later, Pakistani theater owners ended their self-imposed ban and Indian films returned to Pakistani screens in 2017. But investors started questioning whether the movie business was feasible if it suffered after every crisis between the two countries. The first ban on the exhibition of Indian films was imposed by military ruler President Mohammad Khan Ayub after the second India-Pakistan war in 1965. The woes of the local cinema industry were further exacerbated during the era of Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq’s presidency, when higher taxation and strict censorship policies made it impossible for cinema to grow. During those decades, as cinema was gradually fading away, Pakistan’s television soap operas boomed and provided entertainment for the middle classes. Most actors, directors and screenwriters focused on producing them. Film lovers had the limited choice of either watching second-rate vanity projects or pirated versions of Hollywood and Bollywood movies. The decimation of Pakistani cinema — particularly under the rule of General Zia — meant that the country lost most of its 700 single-screen cinemas. Pakistani cinema began to emerge from its long coma in 2006 when Gen. Pervez Musharraf removed the ban on showing Indian movies that had been in place since 1965. Within a few years new multiplexes sprung up in all major cities to meet the high demand for films. By 2011 Pakistan had around 35 multiplex screens; more than a hundred more were being built. Sadly this new infrastructure was restricted to multiplexes as distributors focused almost entirely on attracting the middle classes who could afford higher ticket prices. Single-screen cinemas, along with their less-privileged audiences, were completely ignored and excluded.

The availability of screen space in turn encouraged local filmmakers to venture out and produce films. A turning point came with the success of Shoaib Mansoor’s Bol, the story of a religious family with a transgender daughter, which was produced in 2011 with a local cast and crew. It inspired more Pakistani filmmakers to jump into the fray. Two years later, Pakistan had produced 20 films and many more were being planned. International festivals started showing interest by curating special segments on Pakistani films. The filmmaking fraternity was upbeat that Pakistan would soon be able to tell its own story through movies. The removal of the ban on Indian films in Pakistan also led to talent sharing and creative cooperation between the two countries. Pakistani actors became stars in India; almost every major Indian movie commissioned Pakistani musicians to sing for them (songs are a key element of films in South Asia). And then fate delivered another lethal blow: India and Pakistan almost went to war in February after a suicide attack on Indian forces in Kashmir. An official ban was imposed on exhibiting Indians films in Pakistan.

Three and a half months later, theaters in Pakistan are almost empty again and their owners are now considering laying off employees. A couple of Pakistani movies have turned out to be blockbusters, but the country is still far from producing a consistent stream of movies which can help sustain theaters and create an effective ecosystem for cinema to flourish. Mirza Saad Beg, a manager at Cinepax, the country’s largest theater chain, explained that Pakistan needs to produce and release at least one or two movies every week for theaters to break even.

The current political situation does not offer any hope of a revival of cultural ties between India and Pakistan any time soon. Despite efforts by the previous governments of both Pakistan Peoples Party and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, the state has yet to formulate a uniform film policy or revive a film development department that once supported the growth of local cinema. The arrival of online streaming platforms such as Netflix and Amazon is helping film industries in various other countries grow and attempt new storytelling formats — but they have hesitated from exploring Pakistan and commissioning projects from Pakistani filmmakers. With no other avenues in sight, unless the government finally manages to formulate a robust policy to encourage local cinema and Pakistani filmmakers are able to produce a consistent stream of compelling content that can compete with Bollywood and Hollywood, there is little hope that local cinema can keep breathing.

#Pakistan #PPP - Remarks about NA speaker Bilawal says he will speak truth as PTI seeks apology

Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) lawmakers on Saturday submitted a resolution in the Lower House against PPP Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, demanding that the opposition leader apologise for his remarks criticising the National Assembly speaker, media reports said.

Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) lawmakers on Saturday submitted a resolution in the Lower House against PPP Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, demanding that the opposition leader apologise for his remarks criticising the National Assembly speaker, media reports said.

The resolution, which bore the signatures of Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi, Defence Minister Pervez Khattak, Human Rights Minsiter Shireen Mazari as well as Asad Umar and Shafqat Mehmood, stated that Bilawal had used ‘insulting words’ for Speaker Asad Qaiser.

Bilawal, in a press talk after the budget bill was passed by the National Assembly a day earlier, had accused the speaker of ‘running the House in a partisan manner’. He had gone on to call the speaker a ‘worker (naukar) of the government’ and criticised him for not issuing the production orders of MNAs Mohsin Dawar and Ali Wazir, who are currently under detention.

“Such a personalised attack on the speaker, the Custodian of the House, is an attack on the House and totally unacceptable,” the resolution read. “We demand an apology on the floor of the House.”

In response to the resolution against his remarks, Bilawal said, “Benazir [Bhutto] taught me to speak the truth and I will speak the truth.” “I have a lot of respect for the speaker,” he said in a media talk. “I wrote a letter to the speaker as the chairman of the human rights committee and received a receipt saying that my letter has been received with a stamp from the National Assembly. What are you going to call him when the speaker says on national TV that he did not receive any letter?” he asked.

Bilawal had earlier said that he sent multiple letters to the speaker urging him to issue production orders of Dawar and Wazir.

The PPP chairman further said that the budget has been passed without proper voting. “How can you take such a big decision based on a voice vote?” he asked. “Their [the government’s] biggest problem is that I called them liars and selected. They are not bothered by the economic murder of the masses,” he complained.