M WAQAR..... "A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary.Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death." --Albert Einstein !!! NEWS,ARTICLES,EDITORIALS,MUSIC... Ze chi pe mayeen yum da agha pukhtunistan de.....(Liberal,Progressive,Secular World.)''Secularism is not against religion; it is the message of humanity.'' تل ده وی پثتونستآن

Monday, November 23, 2015

Fighting Just ISIS May Not Be Enough

HUSAIN HAQQANI

The West, led by the United States, won the Cold War because it confronted Communist beliefs in addition to restraining Soviet expansionism. But Western leaders—including all candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination for 2016—are reluctant to acknowledge that the West might be at war with radical Islam, out of concern for the prospect of unleashing a wave of bigotry against all Muslims.

But the falsified history and simplified explanations for Muslim decline that pass for discourse among Muslims has to be debunked if the West is to deny Islamists their raison d’être. The most practical way of denying further recruits to extremist Islamist groups is to systematically question and marginalize the outmoded theology of Islamic dominance at the heart of Islamist radicalism. A campaign to reject the dogma of Islamic supremacism would find many supporters among Muslims tired of the zealotry and self-righteousness of the Islamists.

An ideological struggle against radical Islam does not mean treating 1.4 billion Muslims worldwide as the West’s enemy. This huge population will not quit Islam by listening to television pundits in Europe and North America; nor will a ban on immigration prevent Western converts to radical Islamism from swelling the ranks of ISIS. Rather, it requires Muslims to examine the Islamists’ core belief that they must somehow be forcibly united, and that they have a God-given right to lead the world.

Soon after the 9/11 attacks, al-Qaeda ideologue Sayf al-din al-Ansari explained that the attacks were necessary to challenge the ascendancy of Western civilization. According to him, the Islamic community “cannot move in an orbit set by another.”

The Islamic State’s statement claiming responsibility for last Friday’s attacks in Paris declared that the attackers sought to “cast terror into the hearts” of the West. The attacks in France, patterned on the 2008 attacks in Mumbai, India, came within 48 hours of attacks in Beirut and Baghdad, reflecting the jihadis’ global reach.

Islamists target other Muslims to eliminate pluralism within Islam; causing fear and panic in Western society is part of the jihadis’ strategy to weaken and defeat Western civilization.

The origins of al-Qaeda, IS, and other similar groups lie in recent Muslim history and ideology, not Western foreign policy.

Unlike Europe and North America, Muslim territories did not reach their contemporary status gradually. The British and the French in the Arabic-speaking lands, the Russians in Central Asia, the Dutch in Indonesia, and the British in India and Malaya brought new ideas and technology to Muslim lands as occupiers or colonizers.

Some Muslim leaders, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries, opted to learn from and imitate the West. Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, told a peasant who asked him what Westernization meant: “It means being a better human being.” Others, however, recommended “revivalism,” or a search for lost glory through rejection of new ways and ideas.

Contemporary jihadis use modern means, including the internet and state-of-the-art weapons, to impose medieval beliefs in an effort to reclaim Islam’s global pre-eminence. The Muslim Brotherhood’s Egyptian founder, Hassan al-Banna, called upon Muslims “to regain their honor and superiority” in addition to recovering “their lost lands, their usurped regions and their occupied territories.”

While seeking honor or securing self-determination might be valid political objectives, the belief in the superiority of one’s community of believers only fosters fascism. Muslim countries have nosedived into turmoil, with the rise of those wanting to Islamize the modern world coming at the cost of those hoping to modernize the Muslim world.

There is a huge gap between the Islamist aspiration of dominating the world and the reality of the relatively poor political, economic, and educational status of Muslims in contemporary times. Muslims comprise 22 percent of the world’s population but account for only 7 percent of its economic output.

The number of new book titles published every year in Arabic, the language of 360 million, is the same as those published in Romanian, the mother tongue of only 24 million people. The annual figure for new book titles in Urdu, spoken by some 325 million South Asian Muslims, is comparable to that for Danish, spoken by some 5.6 million.

Muslim leaders and intellectuals have created a narrative of victimhood to explain Muslim debility, which in turn enables extremist groups to offer extreme strategies to change the circumstances. “We are weak and poor because we were colonized by the West” is a common refrain, whereas in reality colonization became possible because Muslim empires had already been weakened by failing to adopt new technologies and modes of production.

The jihadi plan for regaining Muslim pride is to challenge Western dominance by striking fear and terror in the hearts of Westerners. They are aided in their endeavor by the absence of discussion among Muslims of why all major ideas that define the contemporary world—from the joint stock company, banking, and insurance to freedom of speech—emerged in the West, or how these ideas, not just conspiracies and superior military technology, made the West ascendant in the past several centuries.

While the jihadis want a clash of civilizations, most ordinary Muslims are hesitant to examine their history or analyze their community’s prospects. Universities in most of the Muslim world focus on producing doctors, engineers, and people proficient in technical disciplines. As a result, even highly educated professionals embrace conspiracy theories about al-Qaeda and ISIS being Western puppets bent on dividing Muslims. Some who do not support the extremists still see value in their ability to at least challenge the arrogant West.

Military defeat alone will not rid the Muslim world of this intellectual malaise. Islamist movements use the humiliation of fellow believers as an opportunity for the mobilization and recruitment of dedicated followers. The resort to asymmetric warfare—the idea that a suicide bomber is a poor man’s F-16—has followed recent Muslim military defeats.

Yasser Arafat and his al-Fatah captured the imagination of young Palestinians only after the Arab defeat and loss of the West Bank in 1967. Islamic militancy in Kashmir can be traced to India’s military victory over Pakistan in the 1971 Bangladesh War. Revenge, rather than willingness to compromise or submit to the victors, is the traditional response of Islamists to the defeat of their armies.

Islamists represent a strain of revivalist thought that perceives a battle without a specific frontline and not limited in span to a few years or even decades. They think in terms of conflict spread over generations. A call for jihad against British rule in India, for example, resulted in an underground movement that began in 1830 and lasted until the 1870s, with remnants periodically surfacing well into the 20th century.

Western nations, together with Muslim allies, need a winning strategy for that generational conflict. They could encourage Muslims to recognize that success in the 21st century will not come from seeking restoration of the medieval order.

Jihadists are incubated in the anti-Western and anti-Semitic conversations and conspiracy theories that pervade the Muslim world. Islamists murder secularists and force many of them to leave their countries because they fear the seductive power of liberal ideas. In the first half of the 20th century, secular nationalism served as the antidote to Islamism.

But nationalist autocrats bred conspiracy theories themselves while strangulating freedom of thought. Instead of ushering in a Muslim enlightenment, authoritarian secularism only strengthened anti-Semitism and the search for the hidden hand manipulating Muslim nations and depriving them of their manifest destiny. Western nations and their Muslim allies embraced Islamists, who were rather weak at the time, in the context of their efforts to contain communism.

Now may be the time to reignite debate in Muslim countries about the real causes of Muslim debility. Western governments and even private organizations and individuals could help with wider circulation in native languages of material produced by Muslims who question the narrative that aids the Islamists.

Books and movies could be produced reflecting the ways that Muslim decline is caused not by Westernization but by poverty and ignorance, which cannot be over-turned by recreating the 7th century or sporadic attacks on Western cities. Support could be given to anti-Islamist political parties, just as non-communist groups were helped in several vulnerable countries during the Cold War. An international network of Muslim critics of radical Islam could reiterate and refine their message.

Some Muslim governments, notably the United Arab Emirates, have initiated efforts to debate and dispute the radical Islamist worldview. That effort needs to expand to include Western countries with substantial Muslim populations, as well as Muslim countries, which tend to produce disproportionately larger number of Jihadi recruits.

In countries like Pakistan (deemed a Western ally) the Jihadi narrative is sustained by the government and media to help groups that advance regional strategic objectives. But it inadvertently also advances the cause of jihadis that are out of the state’s control.

By refusing to identify radical Islam (not all Muslims) as the problem, Western leaders end up reinforcing the Islamist view that they are succeeding in rattling or confusing the West. A concerted ideological campaign, like the one that discredited and contained communism, run by Muslim allies would be the Islamists’ worst nightmare. It would augment military action and counter-terrorist operations against jihadi safe havens and would prevent the breeding of future jihadis.

The West needs to combat Islamist ideology too.

President Obama’s professed desire to contain the Islamic State is unlikely to succeed without a serious effort by the West and its Muslim allies to question the ideology and steady stream of conspiracy theories that feeds Islamist terrorism. Given the global nature and regenerative capacity of Islamist movements, limited action against one group will only result in the birth of another.

The Islamic State emerged out of al-Qaeda’s ashes just as the Obama Administration was celebrating its successful efforts to locate and kill Osama bin Laden. Military action against IS, though necessary, will likely result in a new mutation, just as al-Qaeda evolved as a violent strain of political Islam preached by groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood.The origins of al-Qaeda, IS, and other similar groups lie in recent Muslim history and ideology, not Western foreign policy.

Husain Haqqani, senior fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington, DC, served as Pakistan’s Ambassador to the United States 2008–11. He is co-editor of the journal Current Trends in Islamist Ideology.

Slow road from Kabul highlights China's challenge in Afghanistan

A new road linking the Afghan capital with a trade hub near Pakistan has been stuck in the slow lane since a state-owned Chinese company took the contract to build it two years ago, bedevilled by militant attacks and accusations of mismanagement.

The 106km (65 mile) highway section running most of the way from Kabul to Jalalabad had been slated for completion in April 2017, and delays will further hurt Afghanistan's ambition to promote economic growth to quell a rising Taliban insurgency.

The setbacks are also a reality check for China, as it seeks to bring stability to its war-ravaged neighbour in part through extensive investment.

A giant copper mine remains untapped despite the involvement of another Chinese state firm, and Afghan officials and politicians are openly questioning Beijing's commitment.

"Overall, the company is far behind (on) the commitments they had given to us. We are not satisfied with the company's general performance," Mahmoud Baligh, Afghanistan's minister of public works, said, referring to the road project.

The work was contracted to Xinjiang Beixin Road and Bridge Group Co Ltd in late 2013 for $110 million, according to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which is financing the road.

It is designed as an alternative to the overburdened and sometimes dangerous highway from Kabul east to Jalalabad, capital of Nangarhar province and a trade gateway to Pakistan.

According to Baligh, insurgents attacked the workers' camp several times at the start of the project, wounding some Afghans and halting work for three months.

A source familiar with the project, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said as little as 3 percent of construction was carried out in the first year.

Another person with knowledge of the project said Xinjiang Beixin changed its Afghan-based management this year because of a lack of proper oversight.

Xinjiang Beixin did not respond to requests for comment, and officials at China's embassy in Kabul declined an interview request.

Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Hong Lei said he did not know about the project, but he added that China firmly supported Afghan reconstruction, had provided a large amount of assistance and had encouraged Chinese companies to get involved.

Winning hearts

While China has been hesitant to get involved directly in foreign entanglements, its companies have shown a greater willingness to engage in countries where security can be challenging, including Libya and South Sudan.

The Kabul-Jalalabad road project underscores for China just how complicated Afghanistan can be.

A Nangarhar official said the highway crossed several districts where tribal elders had offered to keep it secure if locals were employed on the project. Instead, he said, the jobs went to Xinjiang Beixin's Kabul-based joint venture.

"They (the elders) are not helping, and are even not stopping the Taliban," the official said, referring to the militant movement waging war on the government in Kabul.

"If companies do not win people's hearts, then the project will never be implemented."

Xinjiang Beixin has joined forces with Afghan businessman Haji Kateb, who said he holds a 51 percent share in the Afghan partner. Kateb said Nangarhar communities were now on board and vowed the road would be finished.

"There was the danger of the Taliban and also a lack of community cooperation. Now elders have committed to help," Kateb told Reuters. "We are committed to finishing."

Wavering commitment?

China wants a stable Afghanistan, fearing the spread of Islamist militancy to its far western region of Xinjiang.It has been trying to broker peace between the Taliban and Afghan government and stepping up development funding as the United States and its allies scale back theirs.

Since the 2001 ouster of the Taliban to 2014, China gave Afghanistan about $250 million, and it has pledged at least another $327 million by 2017.By comparison, nearly $110 billion have been appropriated in Washington for reconstruction in Afghanistan since 2002.

China's commitment could rise substantially with the $3 billion Mes Aynak mine, one of the world's largest untapped copper deposits, but that has also been disrupted by Islamist militant violence.

State-run China Metallurgical Group Corp (MCC), which has rights to the minerals, has demanded royalties be slashed by almost half, and talks are stalled.

Amrullah Saleh, a politician and former chief of the Afghan national intelligence agency, said he feared the road project was another example of "loose commitment by a Chinese company".

"When they have a contract they can trash it or they can respect it. But they should also be mindful that we are neighbours," Saleh said.

The frustration comes as aid-dependent Afghanistan fears missing out on China's grandiose plan to forge trade and energy links to the Middle East, largely through Pakistan.

The ADB said that after four months of work with police and communities, and strengthening management and staffing to boost performance, the road project was now "in full swing".

"These measures have led to significant improvement," ADB project leader Witoon Tawisook said.

Baligh said he, too, was optimistic, while sounding a note of caution: "Road building projects are a very complicated issue in Afghanistan."

The 106km (65 mile) highway section running most of the way from Kabul to Jalalabad had been slated for completion in April 2017, and delays will further hurt Afghanistan's ambition to promote economic growth to quell a rising Taliban insurgency.

The setbacks are also a reality check for China, as it seeks to bring stability to its war-ravaged neighbour in part through extensive investment.

A giant copper mine remains untapped despite the involvement of another Chinese state firm, and Afghan officials and politicians are openly questioning Beijing's commitment.

"Overall, the company is far behind (on) the commitments they had given to us. We are not satisfied with the company's general performance," Mahmoud Baligh, Afghanistan's minister of public works, said, referring to the road project.

The work was contracted to Xinjiang Beixin Road and Bridge Group Co Ltd in late 2013 for $110 million, according to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which is financing the road.

It is designed as an alternative to the overburdened and sometimes dangerous highway from Kabul east to Jalalabad, capital of Nangarhar province and a trade gateway to Pakistan.

According to Baligh, insurgents attacked the workers' camp several times at the start of the project, wounding some Afghans and halting work for three months.

A source familiar with the project, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said as little as 3 percent of construction was carried out in the first year.

Another person with knowledge of the project said Xinjiang Beixin changed its Afghan-based management this year because of a lack of proper oversight.

Xinjiang Beixin did not respond to requests for comment, and officials at China's embassy in Kabul declined an interview request.

Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Hong Lei said he did not know about the project, but he added that China firmly supported Afghan reconstruction, had provided a large amount of assistance and had encouraged Chinese companies to get involved.

Winning hearts

While China has been hesitant to get involved directly in foreign entanglements, its companies have shown a greater willingness to engage in countries where security can be challenging, including Libya and South Sudan.

The Kabul-Jalalabad road project underscores for China just how complicated Afghanistan can be.

A Nangarhar official said the highway crossed several districts where tribal elders had offered to keep it secure if locals were employed on the project. Instead, he said, the jobs went to Xinjiang Beixin's Kabul-based joint venture.

"They (the elders) are not helping, and are even not stopping the Taliban," the official said, referring to the militant movement waging war on the government in Kabul.

"If companies do not win people's hearts, then the project will never be implemented."

Xinjiang Beixin has joined forces with Afghan businessman Haji Kateb, who said he holds a 51 percent share in the Afghan partner. Kateb said Nangarhar communities were now on board and vowed the road would be finished.

"There was the danger of the Taliban and also a lack of community cooperation. Now elders have committed to help," Kateb told Reuters. "We are committed to finishing."

Wavering commitment?

China wants a stable Afghanistan, fearing the spread of Islamist militancy to its far western region of Xinjiang.It has been trying to broker peace between the Taliban and Afghan government and stepping up development funding as the United States and its allies scale back theirs.

Since the 2001 ouster of the Taliban to 2014, China gave Afghanistan about $250 million, and it has pledged at least another $327 million by 2017.By comparison, nearly $110 billion have been appropriated in Washington for reconstruction in Afghanistan since 2002.

China's commitment could rise substantially with the $3 billion Mes Aynak mine, one of the world's largest untapped copper deposits, but that has also been disrupted by Islamist militant violence.

State-run China Metallurgical Group Corp (MCC), which has rights to the minerals, has demanded royalties be slashed by almost half, and talks are stalled.

Amrullah Saleh, a politician and former chief of the Afghan national intelligence agency, said he feared the road project was another example of "loose commitment by a Chinese company".

"When they have a contract they can trash it or they can respect it. But they should also be mindful that we are neighbours," Saleh said.

The frustration comes as aid-dependent Afghanistan fears missing out on China's grandiose plan to forge trade and energy links to the Middle East, largely through Pakistan.

The ADB said that after four months of work with police and communities, and strengthening management and staffing to boost performance, the road project was now "in full swing".

"These measures have led to significant improvement," ADB project leader Witoon Tawisook said.

Baligh said he, too, was optimistic, while sounding a note of caution: "Road building projects are a very complicated issue in Afghanistan."

Will Kazakhstan Be a Game-Changer in Afghanistan?

By Catherine Putz

Economics and security headlined during Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s two-day visit to Kazakhstan over the weekend, underscoring mutual concerns and painful realities in both Astana and Kabul. Ghani also made what has rapidly become a standard stop by high-level visitors to Astana: delivering a speech at Nazarbayev University. The trip was Ghani’s first official visit to Kazakhstan.

Among the deals settled between the two countries was a contract for 600,000 tons of Kazakh wheat. According to TOLOnews, an Afghan news site, Ghani commented that “Kazakhstan is one of the biggest wheat producers in the region and we need imported wheat in next five years.” He also noted that Kazakhstan is a steel producer and Afghanistan’s infrastructure development plans necessitate a solid supply.

Kazakhstan may not be party to some of the grander-scale regional integration schemes, like the TAPI pipeline or the CASA-1000 project, but it stands as the region’s most successful economy. The boom times seem to be over however, with low oil and gas prices cutting into Astana’s pockets. While marketing wheat and steel to Afghanistan isn’t going to make up the missing revenue, it does further Astana’s goals to act as a regional power and a global player.

According to the Trend, since 2002, Kazakhstan has delivered $20 million in foodstuffs to Afghanistan and has allocated $50 million for Afghan students to study at Kazakh universities. Trend also notes that trade between the two countries amounted to $336.7 million in 2014, up from $251.4 million in 2013. The Astana Timesstated that trade now stands at $400 million.

Part of Ghani’s push for deeper engagement with Kazakhstan might be his country’s stalled detente with Pakistan. TOLOnews commented that “Afghan officials and traders consider Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan as better alternative for import of foodstuff and reconstruction materials instead of Pakistan.”

Security featured heavily in comments during the visit. According to RFE/RL, during his speech at Nazarbayev University Ghani categorized “extremism, alienation and embrace of violence” as regional problems. He reportedly “told students that people from many different countries — including China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan — had been involved in Islamic extremist violence in Afghanistan.”

In its coverage of remarks made by Ghani to Kazakh journalists ahead of the visit, the Astana Times made no mention of Kazakhstan as a potential source of extremists–though they do mention Uzbekistan, Russia, Chechnya, Tajikistan and China. “These people are not citizens of our country and have no problems with Afghanistan,” Ghani reportedly commented. “They have problems in their countries. So, the problem can be solved only through development of a comprehensive regional plan.”

As Tamim Asey wrote in The Diplomat this past summer, in modern history, relations between Afghanistan and its neighbors to the north mostly revolve around security. Central Asian government policies aimed at crushing the rise of extremism might have the opposite effect in breeding resentment between people and their governments, which impacts Afghanistan where many fighters from Central Asia end up. Spillover is Central Asia’s perpetual buzzword in relation to Afghanistan, but the spillover, in a way, went in reverse. For example, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) originated in the the country for which it is named, but was pushed out and into Afghanistan and Pakistan where it has been for more than a decade, fighting alongside the Taliban against the Afghan government.

Afghanistan’s ‘mother of education’ fears girls will be deprived again as Taliban regains territory

Alia Dharssi

When Sakena Yacoobi ran 80 underground schools for 3,000 girls in Afghanistan under the Taliban, some teachers hid books in sacks of wheat and rice to avoid detection.

“It is very hard to operate a school where the students cannot be seen,” says Yacoobi, who is known as Afghanistan’s “mother of education.”

“It was through those procedures, innovation and creativity that we were successful.”

After the Taliban seized power in the mid-1990s and forbade girls from attending school, hiding books was among the more straightforward logistical challenges Yacoobi dealt with to get the secret schools, which were in people’s homes and saw 100 to 150 students per day, up and running.

The children were typically brought by their parents and would enter the schools at intervals, two or three at a time, rather than pouring in at once. Some girls even disguised themselves as boys.

|

Sheikha Mozah, left and and U.S. first lady Michelle Obama, right, award the 2015 WISE Prize for Education to Sakena Yacoobi,

|

Of course, as a leader, I cannot cry in front of people, but there are times that I weep and weep

The students couldn’t talk to one another outside the school or take books home for the night. Meanwhile, the teachers carefully controlled when they came and left. With the help of a multi-grade teaching system developed by Yacoobi and her colleagues, one teacher would teach students from Grades One to Eight in the same classroom.

“These were hard things because any time that you had a group of people gathering together for education, it would be really attacked,” she explains.

Earlier this month, Yacoobi was awarded the WISE Prize for Education at the World Innovation Summit for Education in Qatar for more than two decades of efforts to advance education in Afghanistan, often while risking her own life. She was honoured with a gold medal and US$500,000.

Yacoobi, who was born in Afghanistan, studied and worked in public health in the United States as a refugee in the mid-1980s, but she was desperate to return to Afghanistan and help advance women’s rights — an issue that had bothered her growing up. It was too risky at the time, so she moved to Pakistan, home to millions of Afghan refugees, and founded her first school in a refugee camp there in 1991.

“I saw people suffering. Children were not around the camp running around,” recalls Yacoobi. “(I wanted) to bring some happiness to their lives. The issue was education for me because education changed my life.”

Within two years of starting that school, Yacoobi was managing classes for 15,000 refugee children in Pakistan. The word spread to Afghanistan and communities there asked her to help children inside the country, so, in 1995, Yacoobi founded the Afghanistan Institute of Learning (AIL), a non-profit, to support underground schools. The operation required extensive community involvement, says Yacoobi. The communities who wanted schools provided the classrooms, found teachers and sent representatives to Pakistan to smuggle books, supplies and teacher salaries into Afghanistan.

After the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, Yacoobi’s students came out of hiding. “(The children) were so joyful. They were running around and going to school,” she recalls. “But there was no school … All the buildings were completely destroyed. There weren’t books. There weren’t blackboards.”

Today, with the leadership of Yacoobi, AIL runs 44 learning centres for women and children, four private schools, four clinics, a hospital and a radio station to reach people in remote parts of Afghanistan with information about education and women’s rights. It also provides training to teachers in order to boost the quality of schooling in Afghanistan. But progress is hindered by ongoing conflict within the country and dwindling foreign aid.

In 2001, there were roughly one million children, most of them boys, in school in Afghanistan. In 2013, 8.35 million students were in primary and secondary schools around the country and 39 per cent of them were girls, according to data from Afghanistan’s Ministry of Education.

Even so, the United Nations Children’s Fund reports that 3.5 million children are out of school. The quality of schools is low, the education administration is weak and corrupt, and negative attitudes toward girls’ education remain entrenched in parts of the country, says Arne Strand, deputy director of the Christian Michelsen Research Institute, a development research institute in Norway.

“You find people in Parliament that are heavily against girls education,” adds Strand, who is a political scientist with expertise in education in Afghanistan. “… The change of culture and practice takes a longer time.”

Meanwhile, security in Afghanistan, one of the poorest countries in the world, is deteriorating with the Taliban regaining hold on more territory. AIL is able to operate in only 13 of the country’s 34 provinces because of security concerns.

“We need collaboration. We need help. We need assistance,” says Yacoobi, who worries that the waning international focus on Afghanistan means there won’t be enough funding to keep improving schools or for much-needed supplies to teach children to read and write.

Bombings distract the children who are in school, others have been forced to leave their homes because of the ongoing conflict and many don’t have enough to eat, Yacoobi says. “Of course, as a leader, I cannot cry in front of people, but there are times that I weep and weep.”

Even so, Yacoobi remains optimistic about transforming Afghanistan with education in the long term and dreams of one day opening a university, as well as launching a TV station to promote women’s rights and education. If people learn to think critically and go to school, she argues, they will have better opportunities and the society will change.

“Forty years of war completely devastated, destroyed that country. But it will take another 40 years to rebuild it.”

Bangladesh - Pakistan's statement on hanging of war criminals

Uncalled for and unacceptable

We are outraged by Pakistan foreign ministry's statement expressing 'deep concern and anguish' over the execution of two war criminals who collaborated with the Pakistani forces to perpetrate the most heinous crimes against the Bengalis in 1971. The active participation of these war criminals in these crimes against humanity has been proven in the International Crimes Tribunal following standard proceedings with enough scope for the accused to prove the allegations wrong. In such circumstances we find Pakistan's official stand not only a dishonour to the martyrs of the Liberation War but also unacceptable interference in a country's internal affairs.

This is not the first time that Pakistan has officially condemned the carrying out of sentences handed down to other war criminals. As a nation we feel insulted that the official line of Pakistan should be one of commiseration with those convicted of crimes that should be condemned by any civilised nation. Instead of issuing a formal apology to the people of Bangladesh for the war crimes committed by their own army, Pakistan's government has chosen to side with those collaborators who are part of this shameful history.

It seems that the bigotry and racism that prompted the Pakistani occupying forces to unleash a wave of terror on ordinary people have been carried over by some Pakistani officials since 1971. We had hoped that, after 45 years, Pakistan would have shed this mindset and moved on. Regrettably that has not happened. This has only served to jeopardise any possibility of reconciliation. If the spirit and substance of the tripartite agreement is to be honoured then Pakistan should try the 195 war criminals whose acts it had 'condemned and regretted' in the said agreement.

http://www.thedailystar.net/editorial/pakistans-statement-hanging-war-criminals-176977

#Pakistan, Islamist fringe find common ground

Described by the government as a case of “brazen interference,” the Pakistan Foreign Office statement criticising the hanging of convicted war criminals has drawn sharp protests from the government and the public alike.

The leader of Jamaat-e-Islam Pakistan joined in commenting on the executions, lamenting the loss of a “true friend of Pakistan.”

State Minister for Foreign Affairs Shahriar Alam said the statement issued by Islamabad was significant. “We are frustrated but not surprised that Pakistan issued the statement.”

Pakistan belongs to a minority of one in issuing the statement, the state minister said. “The countries which issued statements two or three years back, they did not even issue anything.”

Bangladesh would not accept negative comments from any country about the war crimes trial and the sentencing of war criminals, he added.

Bangladesh would not accept negative comments from any country about the war crimes trial and the sentencing of war criminals, he added.

Pakistan Jamaat chief Sirajul Huq proclaimed: “Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wajid is killing those people who believed in ideology of Pakistan and opposed separation of East Pakistan.”

The irony of having the Pakistani government and the Jamaat-e-Islam party on the same side of the fence is not lost on most observers.

The fringe Islamist party opposed the creation of Pakistan in 1947 and then, after tweaking its position to survive in the new state, opposed Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, with a disregard for human life that inspires horror and condemnation even two generations later.

Sirajul Huq continued: “It is a black day today because a true friend of Pakistan has been hanged in Dhaka.”

His response to Muhajid’s hanging was reported by Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper. He had earlier issued a call to save his Bangladeshi Islamist ally from “an Indian-backed” government.

His party has never apologised for its role in 1971. Its leaders maintain that its position then was correct.

|

| Pakistan surrenders to India | 1971 war |

Instead, it has chosen to misrepresent universally known historical facts.

State Minister Shahriar Alam said the Pakistani government statement mentions the name of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and its leader Salahuddin Quader Chwodhury.

It also mentions the name of Ali Ahsan Mohammad Muzajid but fails to mention the name of the Jamaat-e-Islami, he said. “It shows which political parties they are attached with.”

Pakistan Jamaat reacted similarly after the execution of Bangladesh Jamaat leaders Abdul Quader Molla and Mohammad Kamaruzzaman for war crimes.

Huq said they were being punished by the Awami League government for their allegiance to Pakistan.

The Pakistanis state, meanwhile, has systematically failed in its obligation to bring to justice those of its nationals identified and held responsible for committing mass atrocity crimes in 1971, Bangladesh’s note verbale said.

It said Pakistan continued to present a misleading, limited, and partial interpretation of the underlying premise of the Agreement reached among Bangladesh, India and Pakistan in April 1974.

“The essential spirit of the agreement was to create an environment of good neighbourliness and peaceful co-existence for ushering in long term stability and shared prosperity in the region. But, the agreement never implied that the masterminds and perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide would continue to enjoy impunity and eschew the course of justice,” it reads.

As per the Bangladesh, India and Pakistan Agreement of 1974, “The Foreign Minister of Bangladesh stated that the excesses and manifold crimes committed by these prisoners of war constituted, according to the relevant provisions of the UN General Assembly Resolutions and International Law, war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, and that there was universal consensus that persons charged with such crimes as the 195 Pakistani prisoners of war should be held to account and subjected to the due process of law. The Minister of State for Defence and Foreign Affairs of the Government of Pakistan said that his Government condemned and deeply regretted any crimes that may have been committed.”

The note verbale said Pakistan could not escape the historic obligation it owed to the people of Bangladesh as well as to the international community in bringing war criminals to justice.

“The government of Bangladesh expects that the quarters/authorities in Pakistan would act responsibly and would refrain from continuing such uncalled for statements particularly on Bangladesh’s internal matters,” it said.

- See more at: http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2015/nov/24/pakistan-islamist-fringe-find-common-ground#sthash.frIHg8Jt.dpuf

Bangladesh - Sector Commanders’ Forum demands unconditional apology from Pakistan

Leaders of Chittagong unit of Sector Commanders’ Forum yesterday demanded unconditional apology for the statement from Pakistan on Sunday’s execution of two war criminals.

The leaders came up with the demand after holding a rally held at New Market in the morning.

Chittagong city, north and south district chapters of Sector Commanders’ Forum called the rally protesting at the daylong countrywide hartal called by Jamat.

The forum leaders also called for shutting down Pakistan Embassy in Bangladesh if unconditional apology is not by Pakistan.

“We have noted with deep concern and anguish the unfortunate executions of the Bangladesh National Party Leader, Mr Salauddin Quadir Chowdhury and Mr Ali Ahsan Mojaheed. Pakistan is deeply disturbed at this development,” said a statement of the Pakistan Foreign Ministry issued on Sunday.

Bedarul Islam Chowdhury, member secretary of Chittagong chapter of Sector Commanders’ Forum, said: “The statement issued by Pakistan on the execution the two war criminals is a testimony of audacity. The statement is also a manifestation of an urge to take revenge for the defeat conceded during the Liberation War in 1971.

“The Pakistan Embassy in Bangladesh should be closed down without any delay if unconditional apology is not sought by Pakistan for the audacious statement,” added Chowdhury.

With the forum’s south chapter President Md Idris in the chair, the rally was addressed among other by city Awami League Law Affairs Secretary Iftekhar Saimul Chowdhury, forum’s leaders Nurul Alam Montu, Nure Alam Siddique, Khaleda Akhtar Chowdhury, Fazal Ahmed and Goury Shankar Chowdhury.

Later, the forum brought out an anti-hartal procession which paraded different points of the city.

- See more at: http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2015/nov/24/sector-commanders-forum-demands-unconditional-apology-pakistan#sthash.uAT198BA.dpuf

Pakistan, ISI "biggest threat" to India & Bangladesh: Bangladesh diplomat

Adviser to Bangladesh's Prime Minister on International Crimes, Wali-ur Rahman, today said Pakistan is an epicentre of terrorism and not only India, but his country has also been a victim of its terror activities.

"Pakistan and ISI have been the biggest threat to us as they keep sending their operatives to India and Bangladesh... ISI is still an epicentre of terror...Not only in these two countries, but they also dispatch their operatives to Nepal, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and all over the SAARC countries," Rahman told PTI, on the sidelines of two-day 'Megacity Security Conference' that began here today.

"They are a destabilising force. They tried to destabilise us too, but failed. They set up 101 training camps on our soil to train Indians to fight against Indians. But we pushed them back with the active support of India. We cannot think that Pakistan should use our land for anti-India activities," Rahman, a former Secretary in Bangladesh's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said.

The conference is being attended by policy makers, law enforcement officials, security experts and leading thinkers representing eight different countries. They will share first- hand experience about dealing with security policy in some of world's megacities such as Mumbai, New York, Istanbul, Chicago, Manila, Dhaka, Nairobi and Mexico.

Terming India a friend in true sense, Rahman, an expert on national security and counter-terrorism, said, "Bengalis are very emotional people. Every Bengali is with us, except two political outfits Jamaat-e-Islami and Bangladesh Nationalist Party, who supported ISI in our country."

"But when Sheikh Hasina took over as the Prime Minister of the country in 1996, she got rid of ISI and sent me to Delhi to meet the then Home Secretary Padmanabhan. I followed his advice, made a list of ISI training centres and successfully eliminated them," Rahman said, adding, there may be a few ISI elements active in the country as of now.

"Pakistan and ISI have been the biggest threat to us as they keep sending their operatives to India and Bangladesh... ISI is still an epicentre of terror...Not only in these two countries, but they also dispatch their operatives to Nepal, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and all over the SAARC countries," Rahman told PTI, on the sidelines of two-day 'Megacity Security Conference' that began here today.

"They are a destabilising force. They tried to destabilise us too, but failed. They set up 101 training camps on our soil to train Indians to fight against Indians. But we pushed them back with the active support of India. We cannot think that Pakistan should use our land for anti-India activities," Rahman, a former Secretary in Bangladesh's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said.

The conference is being attended by policy makers, law enforcement officials, security experts and leading thinkers representing eight different countries. They will share first- hand experience about dealing with security policy in some of world's megacities such as Mumbai, New York, Istanbul, Chicago, Manila, Dhaka, Nairobi and Mexico.

Terming India a friend in true sense, Rahman, an expert on national security and counter-terrorism, said, "Bengalis are very emotional people. Every Bengali is with us, except two political outfits Jamaat-e-Islami and Bangladesh Nationalist Party, who supported ISI in our country."

"But when Sheikh Hasina took over as the Prime Minister of the country in 1996, she got rid of ISI and sent me to Delhi to meet the then Home Secretary Padmanabhan. I followed his advice, made a list of ISI training centres and successfully eliminated them," Rahman said, adding, there may be a few ISI elements active in the country as of now.

Pointing to the helplessness of Pakistan government, Rahman said, "The main plotter of Mumbai attacks is walking freely and we can easily think what kind of position Nawaz Sharif has as Prime Minister there."

http://www.deccanherald.com/content/513545/pak-isi-biggest-threat-india.html

Why Pakistan persecutes the minority Ahmadi group

By Shamil Shams

An angry mob in the Pakistani city of Jehlum burnt down a factory and a mosque belonging to the minority Ahmadi group on blasphemy charges. What are the reasons behind continued persecution of the Ahmadis? DW examines.

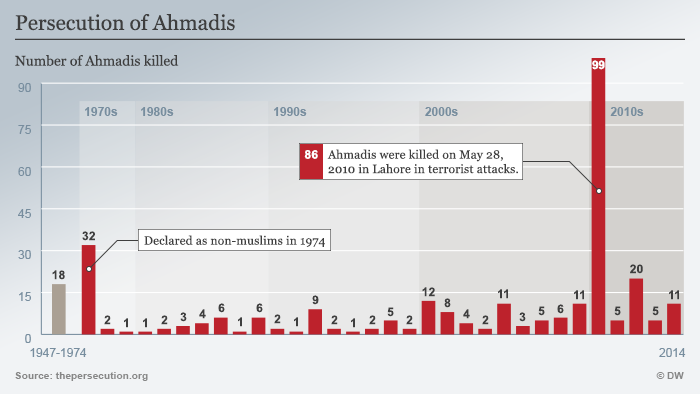

In Pakistan, all you need to lynch Ahmadis or torch their houses and places of worship is an allegation of blasphemy. They are an easy target. Declared non-Muslims in 1974, the Ahmadis face both legal and social discrimination in the Islamic country, and the attacks on their properties have increased manifold in the past decade.

On Saturday, November 21, an angry mob in the eastern Punjab province set ablaze a factory owned by the Ahmadis, after one of its employees was accused of desecrating the Koran.

"The incident took place after we arrested the head of security at the factory, Qamar Ahmed Tahir, for complaints that he ordered the burning of Korans," Adnan Malik, a senior police official in the Jhelum city, told the media.

"We registered a blasphemy case against Tahir, who is Ahmadi by faith, and arrested him after confiscating the burnt material, which also included copies of the Koran," Malik said.

According to local media, after the arrests hundreds of people descended on the factory, setting it on fire.

A spokesman for the local Ahmadi community said three of their members were detained by the police on blasphemy charges.

A day later on Sunday, Muslim protesters attacked and occupied an Ahmadi mosque in a town near Jehlum, as an act of "revenge" for the factory incident.

"A mob attacked our mosque in Kala Gujran, an area in Jehlum, took out its furniture and set it on fire. Then, they washed the mosque and later offered evening prayers in the mosque," Amir Mehmood, a member of the Ahmadi community, said.

Rights activists say that a cleric of a Muslim mosque in the area had urged the people to "punish" the "blasphemers." They also accuse the local administration and the police of not preventing both attacks on the minority group.

Constitutional discrimination

The Islamization of Pakistan, which started during former Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's government in the 1970s, culminated in the 1980s under the former military dictator General Zia ul-Haq's Islamist regime. It was during Haq's oppressive rule when Ahmadis (also known as Qadianis in Pakistan) were banned from calling themselves Muslim and building their mosques in the Islamic Republic. Their places of worship were shut down or desecrated by hard-line Islamists with the support of the state.

Ahmadis, who believe the Messiah Ghulam Ahmad lived after the Prophet Muhammad, insist they are Muslim and demand as much right to practice their faith in Pakistan as other people.

Baseer Naveed, a senior researcher at the Asian Human Rights Commission in Hong Kong, says that Ahmadis continue to be persecuted and attacked in Pakistan with the full backing of the state.

"The government wants to appease Muslim fundamentalists and right wing parties. We see that the Pakistani state continues with its policy of hatred towards religious minorities, which embolden fundamentalists," Naveed told DW.

However, Amin Mughal, a scholar based in London, believes the issue is more political than religious.

"Ahmadis were once a relatively strong group within the Pakistani establishment. The dominant Sunni groups felt threatened by them and axed them out of the state affairs," Mughal told DW.

Collective intolerance

Pakistan has witnessed an unprecedented surge in Islamic extremism and religious fanaticism in the past decade. Islamist groups, including the Taliban, have repeatedly targeted religious minorities in the country to impose their strict Shariah law on people.

According to the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), 2013 was one of the worst years for religious minorities in the country: Several people were charged with blasphemy, many places of worship were burnt down and houses were looted all over the country.

Asad Butt of the HRCP told DW that intolerance was definitely growing in Pakistan, and that many Pakistanis considered blasphemy an "unpardonable crime."

But how and when did Pakistanis become so intolerant towards other religions and their followers?

"The days are gone when we said it was a small group of religious extremists, xenophobes, hate-mongers and bigots who commit such crimes," Karachi-based journalist Mohsin Sayeed told DW. "Now the venom has spread to the whole of Pakistani society," he added.

Butt blames Haq for this. "There was no such issue prior to the 1980s, but when Haq came into power, he Islamized everything and mixed religion and politics," Butt underlined.

Controversial legislation

Blasphemy, or the insult of Prophet Muhammad, is a sensitive topic in Pakistan, where 97 percent of its 180 million people are Muslims. Rights activist demand the reforms of the controversial blasphemy laws, which were introduced by Zia-ul-Haq in the 1980s.

Activists say the laws have little to do with blasphemy and are often used to settle petty disputes and personal vendettas.

The number of blasphemy cases in Pakistan has increased manifold in recent years. Pakistan's liberal sections are alarmed by the growing influence of right-wing Islamists in their country and blame the authorities for patronizing them. Rights organizations also point to the legal discrimination against minorities in Pakistan, which, in their opinion, is one the major causes of the maltreatment of Pakistani minority groups.

"The blasphemy laws should be abolished because they have nothing to do with Islam," Sayeed said. "We have been demanding their repeal for a long time. This demand has sparked a fierce reaction from religious extremists."

Hussain Naqi, a veteran human rights activist and official of Pakistan's independent Human Rights Commission (HRCP) in Lahore, says that blasphemy laws are equally threatening for the majority Muslims.

"The blasphemy cases are mostly about personal issues," Naqi told DW. "In Pakistan, it is very easy for people who want to settle scores with their enemies to accuse them of blasphemy. They know that there are immediate arrests in blasphemy cases, and sometimes people are killed on the spot."

BILAWAL BHUTTO CONDEMNS MURDER OF A KOHAT JOURNALIST HAFEEZUR REHMAN

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, Chairman Pakistan Peoples Party has condemned murder of a Kohat journalist Hafeezur Rehman in village Kalo Khan Banda by armed men in an ambush.

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, Chairman Pakistan Peoples Party has condemned murder of a Kohat journalist Hafeezur Rehman in village Kalo Khan Banda by armed men in an ambush.In a press statement, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari expressed concern over the growing attacks on journalist community in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and urged the provincial government and the law enforcing agencies to provide protection to the newsmen.

He said that killing of the journalist in Kohat was a various security issue and sympathized with the bereaved family and demanded KPK Government to provide adequate compensation to the family besides taking stern action against the killers.

https://ppppunjab.wordpress.com/2015/11/23/bilawal-bhutto-condemns-murder-of-a-kohat-journalist-hafeezur-rehman/