Saudi journalist Safa al-Ahmad discusses BBC Arabic’s feature documentary and the obstacles she faces while reporting on her country of origin

“Any person who asks for his rights is disappeared behind bars.”

The statement could describe circumstances surrounding any number of the democratic struggles now taking place across North Africa and the Middle East. Yet, this grievance comes from an activist in the rigorously-guarded eastern province of Saudi Arabia, where the biggest uprising against the state in its history has persisted over three years, under a near complete media blackout. “The biggest oil field in the world is in Qatif, but what do we find? Nothing but dilapidated houses, poverty, hunger and marginalisation,” he said.

Tumult in the oil-rich region of Qatif, which has seen at least twenty civilians and two police officers killed since 2011, has now emerged more graphically via the efforts of Saudi journalist, Safa al-Ahmad.

Tumult in the oil-rich region of Qatif, which has seen at least twenty civilians and two police officers killed since 2011, has now emerged more graphically via the efforts of Saudi journalist, Safa al-Ahmad.

Against the odds of state-policing, which renders journalism there near impossible (Saudi’s media environment is ranked, by organisations like Freedom House, as among the most repressive in the Arab world), the award-winning al-Ahmad made multiple visits to Qatif over two years to document events there for BBC Arabic. The resulting film, “Saudi's Secret Uprising,” is testament to the potency of a movement that has been largely neglected by the international press.

“Saudi is so badly reported, and not just in the Western media,” said al-Ahmad, who was born and raised in the country and now covers the region from her base in Istanbul. “There is an acceptable, stereotypical image which protest simply does not fit into.”

A fickle global media

Countering this narrative, al-Ahmad’s film, which opened London’s Aan Korb film festival in October, depicts a large-scale and ultimately bloody struggle for rights that echoes those of other countries in the region.

Countering this narrative, al-Ahmad’s film, which opened London’s Aan Korb film festival in October, depicts a large-scale and ultimately bloody struggle for rights that echoes those of other countries in the region.

Saudi Arabia’s eastern province is home to the majority of the country’s Shiite, who make up some 15 percent of the population. Like their more numerous religious counterparts in Bahrain, the minority claims that they are subject to wilful sectarian discrimination by the ruling Sunni monarchy.

The group’s manifold grievances, which range from a denial of basic human and civil rights to political imprisonment and systematic exclusion from the country’s oil wealth and institutions, are not new. (As one of al-Ahmad’s interviewees notes, “for a hundred years, we have been marginalised in Qatif, though it is one of the richest areas.”)

Yet residents have been emboldened by the parallel events of other Arab uprisings since 2011 and have taken to the streets in record numbers. Their demands for reform are powerfully evidenced in al-Ahmad’s film, which combines anonymous and on the record interviews with archival footage from more than three years of protest. Official attempts to portray the unrest as a “limited problem,” are undercut by scenes of overt police violence and killing, alongside thousands-strong street demonstrations bearing the familiar, but here seemingly unthinkable, chants for the fall for the regime.

Despite the unprecedented nature of the investigation, getting the story to air was in itself a struggle. “Nobody wanted to touch it at first,” said al-Ahmad, who had been researching the story since early 2011 for a series of feature reports for the London Review of Books. After the killing of four protestors in Qatif in November 2011, she began pitching to a range of international broadcasters and press outlets.

“Not a single person responded,” she explained. “I began to think, can this really be happening? People are on the streets shouting ‘death to al-Saud’ in a major historical event and nobody wants to look into it? It was not even a blip on international media radars.”

As al-Ahmad noted, widespread disinterest in the story reinforced her sense of bewilderment at the whims of foreign reporting. “The tunnel vision of media is quite disturbing,” she said. “I would love to find out why editors consider three years of protests and killings, the biggest in Saudi Arabia’s history, not newsworthy when there are pages to explore regarding what is happening in Iraq and Syria. It is a disservice to audiences as well as people in the region themselves.”

Al-Ahmad was nonetheless adamant to defy established reporting patterns, through a more multi-faceted portrayal of her country of birth. International media intrigue with Saudi Arabia, as she noted, invariably centres on its state-sanctioned treatment of women. With few exceptions, reporting in recent years has rarely strayed beyond stories of subversive female-driving campaigns to explore a terrain of other human-rights or political abuses. Al-Ahmad acknowledged the importance of women-rights struggles, but was determined not to box herself into a well-worn journalistic niche.

“I felt I had a physical need to tell this story,” she said. “I did not want to do the cliché ‘women’s issues’ stories that media outlets are all interested in, when in Saudi Arabia, there are major structural human-rights problems. I wanted to deal with more intrinsic and basic issues; what is the nature of the relationship between people and their government; and what rights do they have to call for change?”

The people versus the state

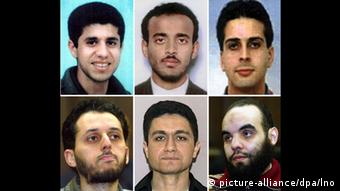

Al-Ahmad’s pursuit of these questions took her into perilous terrain. For over a year, the Saudi authorities refused BBC requests for comment on or cooperation in the story and with full knowledge of this resistance, al-Ahmad undertook her investigations below the radar. (As a Saudi national, she was able to enter the country freely, but being caught filming in the region would have posed dire consequences for al-Ahmad and her sources.) The story brings al-Ahmad into contact with a number of protest-leaders from the province, many of them from the government’s official wanted list. While some agreed to speak on conditions of anonymity, others appeared to spurn the authorities by appearing on the record.

Despite the unprecedented nature of the investigation, getting the story to air was in itself a struggle. “Nobody wanted to touch it at first,” said al-Ahmad, who had been researching the story since early 2011 for a series of feature reports for the London Review of Books. After the killing of four protestors in Qatif in November 2011, she began pitching to a range of international broadcasters and press outlets.

“Not a single person responded,” she explained. “I began to think, can this really be happening? People are on the streets shouting ‘death to al-Saud’ in a major historical event and nobody wants to look into it? It was not even a blip on international media radars.”

As al-Ahmad noted, widespread disinterest in the story reinforced her sense of bewilderment at the whims of foreign reporting. “The tunnel vision of media is quite disturbing,” she said. “I would love to find out why editors consider three years of protests and killings, the biggest in Saudi Arabia’s history, not newsworthy when there are pages to explore regarding what is happening in Iraq and Syria. It is a disservice to audiences as well as people in the region themselves.”

Al-Ahmad was nonetheless adamant to defy established reporting patterns, through a more multi-faceted portrayal of her country of birth. International media intrigue with Saudi Arabia, as she noted, invariably centres on its state-sanctioned treatment of women. With few exceptions, reporting in recent years has rarely strayed beyond stories of subversive female-driving campaigns to explore a terrain of other human-rights or political abuses. Al-Ahmad acknowledged the importance of women-rights struggles, but was determined not to box herself into a well-worn journalistic niche.

“I felt I had a physical need to tell this story,” she said. “I did not want to do the cliché ‘women’s issues’ stories that media outlets are all interested in, when in Saudi Arabia, there are major structural human-rights problems. I wanted to deal with more intrinsic and basic issues; what is the nature of the relationship between people and their government; and what rights do they have to call for change?”

The people versus the state

Al-Ahmad’s pursuit of these questions took her into perilous terrain. For over a year, the Saudi authorities refused BBC requests for comment on or cooperation in the story and with full knowledge of this resistance, al-Ahmad undertook her investigations below the radar. (As a Saudi national, she was able to enter the country freely, but being caught filming in the region would have posed dire consequences for al-Ahmad and her sources.) The story brings al-Ahmad into contact with a number of protest-leaders from the province, many of them from the government’s official wanted list. While some agreed to speak on conditions of anonymity, others appeared to spurn the authorities by appearing on the record.

Among them was Morsi al-Rabih, a young activist leader named among the government’s 23 most wanted. Al-Ahmad met Rabih just hours after a police raid on his home in late 2012, where he narrowly escaped injury. “It is clear they meant to kill,” he told al-Ahmad, “But we are walking the right path. We are demanding our rights.” Within months, in June 2013, Rabih was killed by multiple gunshot wounds during an attempted arrest by security forces.

Among other victims of Saudi Arabia’s state violence, al-Ahmad met the family of the prominent Shiite cleric, Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr, who was recently sentenced to death by beheading on charges of sedition. Since 2011, Saudi authorities have appealed to the country’s Shiite clergy to help quell the protests, but Nimr has remained one of the most vocal critics of the regime. (Footage of a sermon shortly after the killing of a Saudi government official in 2012 shows the cleric exclaiming, “Hopefully he takes the rest – al-Saud, al-Khalifa, Assad!”) Nimr achieved notoriety for his campaigns around civil equality, socio-political inclusion, women’s rights and political detention. But his more recent denunciation of violence tactics signals the divisions within an uprising that has radicalised over its course.

The gradual infiltration of more forceful tactics - from Molotov cocktails to handguns - in protestors’ arsenal is documented by al-Ahmad herself, as the escalation of brutality among the Saudi authorities is paralleled in the views and practices of some activists. “There was a real moment of hope in the beginning that this peaceful protest might actually be a way to gain reform,” she said. “But like in other uprisings, the response of governments has left very little room for people who believe in non-violence to explore other tactics. It is always much easier to be violent than non-violent.”

Enemies of the regime

Recent instances of opposition violence have done much to confirm the narrative projected by Saudi authorities of an extremist movement, spurred by sectarianism with support from Iran. As al-Ahmad noted, the government has helped create the enemy it needs. Yet violence by protestors has also polarised communities within Qatif itself. While so many have suffered the brutal effects of the crackdown, few have felt any tangible benefit from the campaign’s promise of reform.

“It was really courageous of people to take to the streets, not even covering their faces, and dare to plainly demand their rights,” said al-Ahmad. “Now many people won’t let their children leave the house. That was one of the saddest things - people were trying to be peaceful and it escalated completely out of control. Our government does not want to try to understand us.”

Saudi officials repeatedly declined to engage with al-Ahmad’s story, refusing comment on the protests and denying access to police and security force sources. Since the film’s screening at a number of international film festivals, they have nonetheless reportedly contacted the BBC to express their extreme displeasure at the characterisation of events. This acrimony has been reflected in local media sources which have typically denounced the film as sectarian propaganda and accused protestors of foreign-backed terrorism.

Among other victims of Saudi Arabia’s state violence, al-Ahmad met the family of the prominent Shiite cleric, Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr, who was recently sentenced to death by beheading on charges of sedition. Since 2011, Saudi authorities have appealed to the country’s Shiite clergy to help quell the protests, but Nimr has remained one of the most vocal critics of the regime. (Footage of a sermon shortly after the killing of a Saudi government official in 2012 shows the cleric exclaiming, “Hopefully he takes the rest – al-Saud, al-Khalifa, Assad!”) Nimr achieved notoriety for his campaigns around civil equality, socio-political inclusion, women’s rights and political detention. But his more recent denunciation of violence tactics signals the divisions within an uprising that has radicalised over its course.

The gradual infiltration of more forceful tactics - from Molotov cocktails to handguns - in protestors’ arsenal is documented by al-Ahmad herself, as the escalation of brutality among the Saudi authorities is paralleled in the views and practices of some activists. “There was a real moment of hope in the beginning that this peaceful protest might actually be a way to gain reform,” she said. “But like in other uprisings, the response of governments has left very little room for people who believe in non-violence to explore other tactics. It is always much easier to be violent than non-violent.”

Enemies of the regime

Recent instances of opposition violence have done much to confirm the narrative projected by Saudi authorities of an extremist movement, spurred by sectarianism with support from Iran. As al-Ahmad noted, the government has helped create the enemy it needs. Yet violence by protestors has also polarised communities within Qatif itself. While so many have suffered the brutal effects of the crackdown, few have felt any tangible benefit from the campaign’s promise of reform.

“It was really courageous of people to take to the streets, not even covering their faces, and dare to plainly demand their rights,” said al-Ahmad. “Now many people won’t let their children leave the house. That was one of the saddest things - people were trying to be peaceful and it escalated completely out of control. Our government does not want to try to understand us.”

Saudi officials repeatedly declined to engage with al-Ahmad’s story, refusing comment on the protests and denying access to police and security force sources. Since the film’s screening at a number of international film festivals, they have nonetheless reportedly contacted the BBC to express their extreme displeasure at the characterisation of events. This acrimony has been reflected in local media sources which have typically denounced the film as sectarian propaganda and accused protestors of foreign-backed terrorism.

Other critics have charged al-Ahmad with journalistic distortion and imbalance, claiming that she has airbrushed violence committed against police by protestors and portrayed as heroes those who merely “want the blood of security forces on their hands.”

Al-Ahmad says she has also personally felt the force of the state. She has been widely (and violently) denounced online by anonymous supporters of the regime, and as foreseen, Saudi authorities have instructed her not to return to her country. This has been a high price, but the risks were carefully calculated.

Countering official Saudi views, many affirmative voices inside and outside the country have applauded al-Ahmad for exposing what they see as tangible and ongoing injustices. Although she insists that it would have been a stronger story had Saudi authorities conceded to requests for interview, al-Ahmad nonetheless describes the work as a pivotal moment in her career.

“This was the culmination of my experiences as a journalist,” she explained. “I wanted to better understand my country while still distancing myself from the story, to understand local people while relating their struggle to the outside. It was a big personal decision and if I was going to take the risks, I knew it had to be worth it.”

Representatives of the Saudi government were not available for comment on the film or its reception in the UK.

“This was the culmination of my experiences as a journalist,” she explained. “I wanted to better understand my country while still distancing myself from the story, to understand local people while relating their struggle to the outside. It was a big personal decision and if I was going to take the risks, I knew it had to be worth it.”

Representatives of the Saudi government were not available for comment on the film or its reception in the UK.

- See more at: http://www.middleeasteye.net/in-depth/features/reporting-saudi-s-secret-uprising-1393709983#sthash.V625J9Hr.dpuf

-